The Glorious Revolution

Posted on 9th April 2023

On 6 February 1685, as he lay upon his deathbed breathing his last, King Charles II converted to the Roman Catholic faith. He would like to have done so sooner but as the long struggle to ensure his already Catholic brother James succeeded him had revealed any pro-Catholic sentiment expressed on his part was met with a hostility the vehemence of which if allowed to fester, could imperil the throne. So, he kept his powder dry and secured the Stuart Dynasty repaying the debt owed to his father, even if he believed his brother’s despotic temperament would see him deposed within three years.

James had converted to the religion of their mother Henrietta Maria in 1668, but it was kept secret until the passage of the Test Act in 1673 that called upon all civil and military officials to denounce Catholic practices and accept the Eucharist under the auspices of the Anglican Church of England.

James had refused to do so instead resigning from his post as High Lord Admiral, thereby revealing his conversion. That he did so and was willing to forego material gain for the sanctity of his faith early made some tremble at the prospect of his becoming King.

For this reason, Charles had publicly opposed his conversion stating that it had only been tolerated on the grounds that his daughters Mary and Anne to his first wife Anne Hyde had been raised in the Protestant faith. Privately he was more sympathetic and later permitted James to marry the Catholic Italian Princess Mary of Modena.

The fear of Catholicism and the return of auto-da-fe to the streets of London and elsewhere pervaded every aspect of society in Restoration England whether it, be in religion, politics, science, or the arts. That the heir to the throne was a follower of the despised ‘Scarlet Whore of Babylon’ was a very serious matter in a country where only 1 in 50 of the population remained adherents of the Old Faith, even if the figures were skewed somewhat by the penalties imposed on those who openly did so.

Anti-Catholic conspiracy theories such as those which abounded during the Great Fire of London or the rumour that Jesuit Nightriders stalked the byways of rural England murdering Protestant Clergymen were readily believed. Indeed, many had even lost their lives because of accusations made by such an obvious fraud as Titus Oates. Some already believed the King to be a secret Catholic, a suspicion that might have had severe repercussions had they known he’d been colluding with Louis XIV of France and pocketing large bribes as a result.

The fear that England would again revert to Roman Catholicism as it had done previously under Queen Mary made the prospect of bloody and ruinous civil war loom large.

The leading Whig politician in the House of Commons Sir Anthony Ashley-Cooper, Earl of Shaftesbury, was determined to exclude James from the line of succession in favour of the King’s first-born, but illegitimate son, James Scott, Duke of Monmouth, assuredly Protestant and no friend of his uncle. Charles was no less determined to secure his sainted father’s legacy and preserve the throne for his brother.

Charles would see off the Exclusionists in Parliament via a mixture of Majesty, political artifice, and veiled threat but the failure of the Exclusion Bill would lead directly to the Rye House Plot and the attempted assassination of both the King and James as they returned from Newmarket Races.

The plot was thwarted but the arrest of the conspirators revealed the nature of the antagonism towards the Duke of York’s likely succession for they were not political radicals or religious fanatics but members of the social elite.

The Exclusion Crisis and the Rye House Plot had only served to further enhance in James an already well-honed propensity toward paranoia.

Nevertheless, when Charles finally died after having, in his own words, taken an unconscionable time in doing so, the succession of King James II went uncontested and as the protestations of loyalty flooded in the peaceful transition of power was greeted with relief and no little rejoicing, particularly on the part of the people.

The new King James reciprocated in kind promising not to penalise those who had advocated for his exclusion and pledging to uphold the rights and freedoms of the people; but it wouldn’t be long before the old demons re-emerged in the form of his nephew the Duke of Monmouth.

In June 1685, Monmouth landed at Lyme Regis in Dorset with just 80 followers and the declaration that he was the true heir and defender of the Protestant faith. At the same time as Monmouth was rallying support in the West Country the Duke of Argyll was doing the same in Scotland. The fact that the banner of rebellion had been raised and at opposite ends of the country was a worry for James but as it turned out Argyll’s rebellion was easily crushed. Monmouth however, posed a more serious threat and it would take a pitched battle at Sedgemoor (the last fought on English soil) to defeat him.

Monmouth, who had abandoned his army in the field, was discovered two days later hiding in a ditch disguised as a yeoman farmer.

Any notion that those who opposed James’s right to rule might be treated leniently during the honeymoon of his reign, were soon dispelled by the ‘Bloody Assizes’ presided over by the notorious Judge Jeffreys.

A vivid account of the George Jeffreys has been left us by Gilbert Burnet, previously Chaplain to Charles II:

“His behaviour was beyond anything heard of in a civilised nation. He was perpetually either drunk or in a rage, more like a fury than the zeal of a judge. He required the prisoners to plead guilty. And in that case, he gave them some hope of favour, if they gave him no trouble; otherwise he told them he would exercise the letter of the law upon them in its utmost severity. This made many plead guilty who had a great defence in law. But he showed no mercy. He ordered a great many to be hanged immediately without giving them a minutes time to say their prayers. England had never known anything like it.”

There could be little doubt that Jeffreys was acting upon the King’s instructions for no greater mercy was afforded his own nephew despite Monmouth falling to his knees and begging for his life.

On 15 July, he was taken to Tower Hill and beheaded.

With the execution of both Monmouth and Argyll it seemed that the threat to James’s rule had been removed but it wouldn’t have been lost on him that both had sailed for Britain from ports in the Dutch Republic governed over by his nephew and son-in-law William of Orange.

The rebellion may have been crushed but it clearly unsettled James as the early sense of compromise and reconciliation gave way to a desire to assert his authority over those, he feared were his enemies. He now demanded the retention of a large standing army and used the powers invested in him as King to ignore the Test Act and appoint many Catholic Officers to its ranks. When Parliament complained he dissolved it.

In January 1686, two letters were found among Charles II’s private papers written in his own hand that advocated for Catholicism over the Protestant faith. James seized upon this and not only had the letters published but challenged the Anglican Church to refute the arguments espoused, writing to the Archbishop of Canterbury:

“Let me have a solid answer, and in a gentlemanly style, and it may have the affect you so desire and bring me over to your Church.”

James had decided to pick a fight his brother had wisely backed away from twenty years earlier and the Archbishop of Canterbury’s disinclination to respond he wrongly interpreted as agreement.

By the spring of 1686 James had already purged the Bench of Judges and in May that year brought a Test Case before it on behalf of a Catholic Officer to whom he had granted dispensation. He had earlier dispensed with the Test Act in recruiting more than a hundred Catholic Officers to the Army.

The Court ruled in his favour, the Lord Chief Justice read out the decision:

“The Kings of England are sovereign princes; the laws of England are the King’s laws. It is an inseparable prerogative of the Kings of England to dispense of penal laws upon particular necessary reasons, and of those reasons the King himself is sole judge.”

The verdict only encouraged him to go further.

On 4 April 1687 James issued his Declaration of Indulgence and Liberty of Conscience. It was intended to establish freedom of religious worship in the British Isles by which he primarily meant Catholic worship. He used his power as King to remove penal religious laws. By doing so he was asserting his right, as he saw it, to suspend laws passed by Parliament - it was a well-trodden path and one that had not ended well for his father.

The Declaration of Indulgence suspended not only the penal laws against Catholics but was also warmly received by dissenting Protestant sects such as the Quakers, Baptists, and Methodists who likewise benefitted and encouraged by the response, particularly the very public support he received from the eminent Quaker William Penn, James even embarked upon a speaking tour to sell his policy to the people telling audiences:

“Suppose there should be a law made that all black men should be imprisoned, it would be unreasonable, and we have as little reason to quarrel with other men for being of different religious opinions as for being of different complexions.”

But it was a step too far and not well-received by many within the Protestant Establishment whether they, be Whig or Tory. Relations with the Monarchy were strained and that they did not break was largely down to the King’s age (he was 55 years old, quite advanced for the time) and the fact that the heir to the throne his daughter Mary was a convinced Protestant and married to William of Orange.

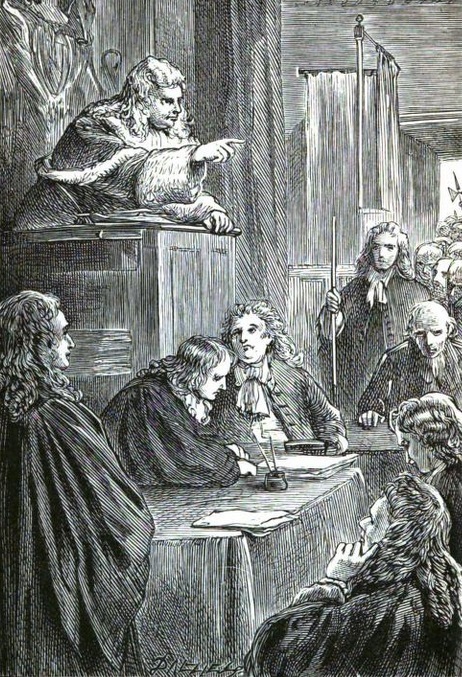

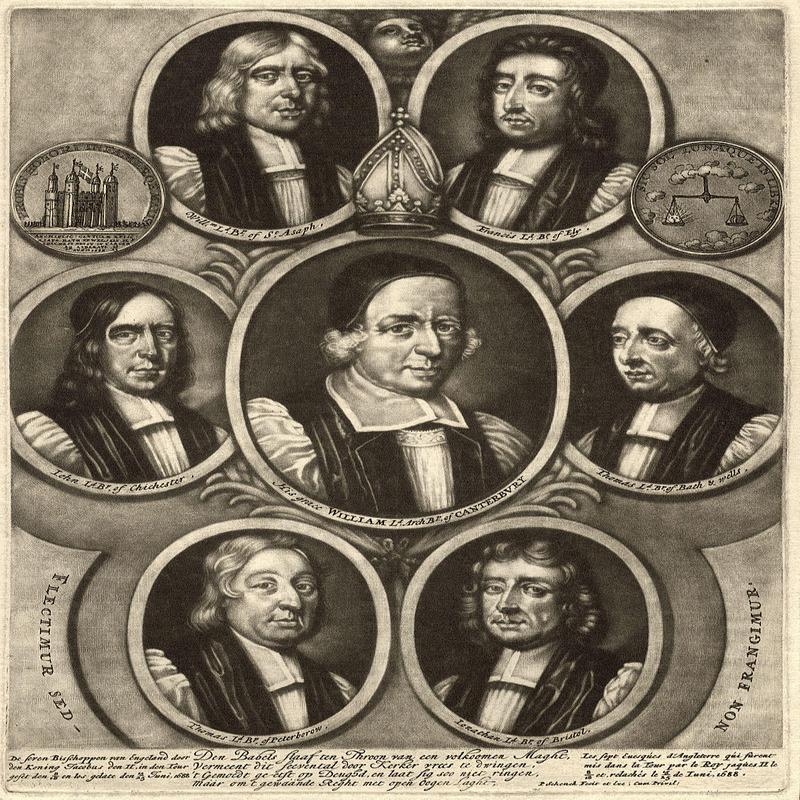

A year after its introduction in April 1688, James had his Declaration of Indulgence re-issued with the demand that it be read from the pulpit of every Church the length and breadth of the country. It was an order largely ignored and when seven Bishops, among them the Archbishop of Canterbury William Sancroft wrote to the King, in suitably deferential terms that he might reconsider his religious policy? James had them arrested and charged with seditious libel. When in May his Council recommended caution, he told them:

“God hath given me this dispensing power and I will maintain it.”

Informed that there was little public support for his stance and advised once more to drop the case, James steadfastly refused prompting his new Lord Chancellor, Judge George Jeffreys of the Bloody Assizes, to caustically remark:

“Is the King willing to take advice from his Ministers or is the Virgin Mary to do it all.”

On 30 June the seven Bishops were acquitted of the charge to great public rejoicing and the entire affair had not only been a personal humiliation for the King but was a first indication of his waning authority. Even so, it did little to divert James from his chosen course of action and he continued to assert his right to rule as he had before he begun a purge of those in official positions courtesy of the Crown who opposed his religious policies ordering that Lords Lieutenants in the counties answer three questions that must then be put to all Justices of the Peace present and future:

1) Do you consent to the Test Act?

2) Will you assist candidates to the bench who do?

3) Will you accept the Declaration of Indulgence?

Those who provided unsatisfactory answers would either be dismissed from or denied the position at least where the new rules were applied for opposition was growing.

James was also eager to alter the makeup of Parliament in his favour and on 24 August 1888, moved the writ for new elections. At the same time, he continued to revoke previously issued Charters of rights and freedoms.

Fears that James shared the same ‘Divine Right’ tendencies of his father Charles I had long been expressed and it now seemed to many that he desired to create a Catholic Absolutist State like that of Louis XIV in France. It almost certainly wasn’t true, at least in its most extreme form, but such was the mistrust on both sides that neither side was any longer listening to the other.

An alliance of Whigs and Tories had already formed to oppose the King’s religious policies and reform of the Institutions but unable to do so effectively in England they looked elsewhere for support and the man they alighted upon was William of Orange, the Stadholder of the Netherlands and great Protestant hero.

William was the obvious choice for his opposition to Louis XIV and long association with England, though he had no great love for the country. He was also married to James’s daughter Mary, was related to the Stuart Dynasty by blood, and had spent considerable time at the Royal Court during the reign of Charles II.

William, on his part, was deeply concerned that should James succeed in transforming the country as he wished then an alliance with France would assuredly follow, and that such an alliance would threaten the independence of the Dutch Republic.

His agents in England had been in communication with the King’s opponents for some time and he had already taken out a loan on the Amsterdam Stock Exchange and made plans for invasion, but he did not want to be seen as the belligerent, neither did he wish to become engaged in a prolonged conflict with a notionally Protestant ally. He was aware that the Dutch were rightly concerned that his absence along with that of his army would leave the country vulnerable and could be exploited by the French. He demanded an invitation to relieve England of its burden and he wanted it in writing.

The matter acquired greater urgency when on 10 June 1688 Mary of Modena gave birth to a healthy baby boy James Francis Edward Stuart. The King had been expected to die without siring further children thereby leaving the throne to his safely Protestant daughter Mary, now he had a Catholic son and heir.

Few in the country believed in the birth and the rumour soon spread that the baby had been kidnapped and smuggled into the Royal Bedchamber hidden in a warming pan; a rumour the source of which was believed to be the King’s youngest daughter Anne who despised her stepmother and her father’s religious convictions.

The threat of a Catholic Dynasty had now become very real and there was no longer room to give James the benefit of any doubt.

Prominent people from across the political divide united to oppose the King among them the Earl of Danby, the Earl of Devonshire, the Earl of Shrewsbury, the Earl of Orford, the Earl of Romney, Viscount Lumley, and Henry Compton, Bishop of London. They were to become known as the ‘Immortal Seven.’

The prospect of a Catholic heir now induced them to send the letter William longed for particularly as he had now been deprived of inheriting the throne via his marriage to Mary who would have become Queen Regnant upon her father’s death.

The letter which had originally been drafted by Henry Sydney, Earl of Romney on the day the bishop’s had been released from the Tower of London but since updated was despatched in secret and contained the signatories names where previously they had communicated in code, they were after all committing treason.

It was received on 30 June 1688:

“We have great reason to believe, we shall every day be in a worse condition than we are, and less able to defend ourselves, and therefore we do earnestly wish we might be so happy as to find a remedy before it is too late for us to contribute to our own deliverance.”

They then proceeded to admonish William on the missive he had sent James congratulating him on the birth of his son:

“And we must presume to inform Your Highness that your compliment upon the birth of the child (which not one in a thousand here believes to be the Queen’s) hath done you some injury.”

They went on to assure William that the state of the Navy was poor, that there was great dissent within the Army, and that both were close to collapse which was only partially true at best. If anyone’s morale was close to collapse it would be that of James himself.

More reassuring perhaps was the letter William received on 14 August from James’s finest General, John Churchill: “I owe it to God and my country to put my honour in the hands of Your Highness.”

It was a betrayal which for the time being would remain a secret.

While William made his final preparations to invade his agents were busy in London distributing propaganda making clear his intentions in the hope of paving the way to a peaceful entry into the city.

On 30 September, William issued his Hague Declaration whereby he made it clear that it was not his intention to depose its King but merely to maintain Protestantism in England. He did not desire the throne, nor did he intend to conquer the land. Upon his arrival in England, he would have 60,000 copies of the Hague Declaration printed and distributed far and wide.

William’s Armada was a large and powerful one, 463 ships, 49 of which were Men-of-War, manned by 40,000 sailors but his army was relatively small just 15,000 men, around half the total available to King James, but he found many willing recruits from among those in the West Country still smarting from the brutal retribution delivered upon them by Judge Jeffreys and his Bloody Assizes.

Upon learning of William’s intention to invade James became immediately more conciliatory revoking many of his previous strictures. On 3 October alone, he agreed to abolish the Ecclesiastical Commission, close all Roman Catholic Schools, restore the Protestant Fellowes of Magdalene College, enforce again the Act of Uniformity in religion, the Lords Lieutenant were invited to resume their functions in the Counties, Tory Squires were urged to become Magistrates again, and he begged the bishop’s to forgive any previous misunderstandings. But it was all too little too late. James had shown his hand and he could not now conceal it in a velvet glove no matter how fine the material.

The wind however, had not been in William’s favour and it wasn’t until 5th November (the anniversary of the notorious Gunpowder Plot) that it suddenly and unexpectedly changed direction allowing him to land at Torbay in Devon. In no hurry to engage the Royal Army stationed at Salisbury and thereby barring his way to London, William proceeded to consolidate his position in the West Country.

The King joined his army on 19 November in a foul mood, uncertain what to do, and in pain from a nasal infection that subjected him to regular nosebleeds which may have been the result of a nervous condition.

At Salisbury he could have ordered his army to advance upon William before he was fully prepared, but he didn’t. Instead, he dithered uncertain as to the loyalty of his own army. He had received reports of orders being disobeyed, of Catholic Officers being roughed up. Would his army fight?

It was while he was at Salisbury that he learned of John Churchill’s defection and that his younger daughter Anne had pledged her support to William, a betrayal that hurt him deeply.

His Army Commander the Earl of Feversham also did little to instil confidence suggesting the King should order a withdrawal should William advance suddenly and without warning. James needed little encouragement and ordered a withdrawal anyway.

Following the King’s hasty and unexpected departure William chose to remain in the West Country rather than set off in pursuit. In the meantime, channels of communication were set up between the King’s people and those of William of Orange, but negotiations were undertaken with scant sincerity on either side. James was playing for time and back in London continued to make concessions in the hope of shoring up his support while William hoped that the time provided would bring the King to his senses, make him realise his position was hopeless and convince him to abdicate.

Except the King’s position wasn’t hopeless, he still had a strong army, the navy remained to all intents and purposes loyal, and the people hadn’t risen up in revolt. It would be his own exaggerated fears and bitter sense of betrayal that led to his downfall.

He remained haunted by the fate of his father who had died on the scaffold having earlier entered negotiations with his Parliament and the army. He felt he could neither trust William nor his own Parliament with the safety of his family, in particular his son. He also remembered all too well his own ruthlessness in dealing with his nephew Monmouth.

In truth James no longer trusted those closest to him and was already making plans to flee. On 9 December his wife and baby son sailed for France. James was to follow two days later but his own escape did not go according to plan. Late at night and disguised as a priest he took a boat down river dropping the Great Seal without which no Parliament could lawfully sit into the Thames as he did so. But he and his small entourage were intercepted by fishermen in the Thames Estuary near Sheerness who believing they captured a Jesuit spy returned him to London.

Much to his surprise James was greeted by cheering crowds who still considered him their rightful King and for a time at least he felt confident enough to resume government convening a meeting of the Privy Council and sending the Earl of Feversham to resume negotiations with William.

It was only now however, learning of the King’s attempted flight, that William seriously considered seizing the throne. He informed James that he was advancing on London and could not guarantee his safety should he meet resistance and hostilities break out. It was an open invitation for James to flee once more and he took it. Placed under armed guard at Rochester Castle supposedly for his own protection orders were given that the King should not be prevented from leaving if he chose to do so. On 23 December, he took ship for France.

A tyrant had been deposed and a Catholic Dynasty avoided and all for the minimum of bloodshed and social disruption, fewer than a hundred dead, and a spattering of anti-Catholic rioting. It truly had been a ‘Glorious Revolution.’

An interregnum now occurred as William took over the de facto reins of power but only courtesy of the Peers of the Realm. A more long-term solution had to be found so a convention was to be held and elections called.

William feared that Parliament would only seek to make him Regent leaving the way open to a Stuart Restoration. His primary concern had always been the Dutch Republic and the events of the previous two months had made the prospect of a hostile England in an alliance with Louis XIV of France more likely not less should James or his son ever return to the throne. He made it clear in a private meeting with Lord Halifax that should he be offered only the Regency then he would return with his army to the Netherlands thereby facilitating the return of a vengeful James. It was a threat he would repeat again and again.

But both Houses of Parliament were divided as to whether the throne was even vacant let alone that it should be offered to William. Although James’s reforms had been opposed by members on both sides of the political aisle it had been less than thirty years since the Monarchy had been restored to much public rejoicing followed the failed experiment with Republicanism, to dismantle what had only recently been recreated some feared threatened a return to civil war. Others saw an opportunity for a new settlement that would cement the primacy of Parliament in English political life once and for all.

On 2 February 1689, the House of Lords rejected the motion to appoint William Regent by 51 votes to 48 votes but a little later they also opposed the motion to make him King by 52 votes to 47 votes. The Whig dominated House of Commons was strongly in favour of doing so by 282 votes to 151 votes.

The impasse was effectively broken by William himself when he made it clear that he was willing for his wife Mary to be the nominal Monarch and that her offspring and those of her sister Anne would take preference in the line of succession. No doubt, Mary’s barrenness following an earlier miscarriage and his own homosexuality made William’s decision easier that might otherwise have been the case. Their assent to the throne would not be without caveats, however – a Bill of Rights.

On 13 February, in the very building where 40 years earlier Charles I had stood on trial for his life the Bill of Rights, a new settlement for England was read out in the presence of both William and Mary.

William did not exactly have to feign indifference and his ennui was evident and plain to see but then this was an English affair, a cleaning of the house. Nonetheless, its significance could not be denied and without it there would be no coronation.

The Bill of Rights was designed to encapsulate the ancient rights and liberties of England, but it was also intended to restrict the powers of the Monarch.

1) The Crown cannot suspend the laws made in Parliament thereby abolishing the King’s dispensing powers.

2) The Crown cannot raise taxation except through, and with the consent of Parliament.

3) England cannot have a Standing Army without the consent of Parliament.

4) It is inconsistent with the safety and welfare of this Protestant Kingdom for the Monarch to be a Papist Catholic, or to be married to a Papist Catholic.

Any new Monarch would also have to swear a revised oath following the Coronation Oath Act of 1688:

“I solemnly swear to govern the people of this Kingdom of England, and the Dominions thereunto belonging, according to the Statutes in Parliament agreed on, and the laws and customs of the same.”

On the very same day as William and Mary’s Coronation news reached London that James II had landed with an army in Ireland.

The deposed Stuart Monarch’s reappearance in the form of a bad penny was to be brief. His army was decisively defeated by William at the Battle of the Boyne on 1 July 1690, bringing to an end his attempt to regain the throne by force.

William and Mary were to reign as joint Monarchs until the Queen’s death from smallpox on 28 December 1694, following which the increasingly unpopular William continued to reign on his own until his own death on 8 March 1702, aged 51, from injuries sustained in a fall from his horse after it stumbled on a molehill.

Following his defeat in Ireland, James returned to France where he established a Court in Exile at the Chateau of St-Germain-en-Lay courtesy of Louis XIV. He died on 16 September 1701 aged 67, but the Stuart claim to the throne did not die with him and repeated attempts were made at a Restoration culminating in the defeat of his grandson James Edward Stuart “Bonnie Prince Charlie” on the barren windswept moor of Culloden in April 1746.

While James railed with bitter resentment at the ingratitude of his people and the betrayal of his own children William was to introduce his own Act of Toleration, but it referred only to the Dissenting Protestant Sects which was required if only because he was a member of one – the Dutch Reformed Church. As head of the Church of England he would later convert to Anglicanism. Catholic Emancipation was not achieved until 1828.

The settlement that followed the Glorious Revolution seriously curbed the authority of the Monarchy and established Parliament as the primary source of political power in Britain. The Bill of Rights also set certain ground rules that if transgressed would provoke a constitutional crisis. Together they helped paved the way to Britain’s development into a Parliamentary Democracy.

There remained those who could not reconcile themselves to the new situation and not only among those abandoned at the Court of King James near Paris who believed Kingship was ordained by Divine Right and not by appointment of Parliament, a romantic notion perhaps which like all romances soon becomes jaded, is fondly remembered, but with little practicable application soon withers on the vine.

Tagged as: Tudor & Stuart

Share this post: