The Haymarket Riot

Posted on 31st March 2022

The late nineteenth century saw the United States undergo enormous industrial expansion alongside similarly large-scale immigration from those fleeing the Old World seeking a better life in the more prosperous New. During the 1880’s alone millions of immigrants entered the USA mostly Italians and Jews from but also from elsewhere such as Scandinavia. Indeed, 9% of the entire population of Norway left their home shores for the United States during this period joining an already large Irish and German immigrant population. But the streets are rarely paved with gold and for the most part they found employment in the manufacturing industry and unregulated sweat shops of the major East Coast cities where the hours were long and the pay poor. The freedoms enjoyed in the United States may have provided opportunity for the brightest and the best but left many more even among the more industrious derelict and without hope.

There was also little sympathy for those who fell beside the wayside for required as they were as a source of cheap labour the reception from the locals who resented not only their religion but the Old-World politics, they brought with them was far from warm. There was little desire to accommodate them in any way either from employers or the Civil Authorities and in many respects, it was a free-for-all where the strongest prospered and the weakest were subsumed back into the poverty they had risked so much to escape - it wasn’t the European way where socialism thrived, and collective action was the order of the day.

Despite the opposition of employers Trade Unions were formed with the largest being the Knights of Labor which could boast a membership of over 800,000 by the late 1880’s. They campaigned on the issues we are familiar with today, higher wages, fewer hours, and better working conditions but they were fiercely opposed by employers who often saw their attempts at collective action as un-American and part of an immigrant plot inspired by close links to the Vatican in Rome. Rather than negotiate they often chose instead to impose lockouts, use scab labour protected by the police, or even employ the Pinkerton Detective Agency and others to bully and intimidate workers. Rarely did an industrial dispute pass without violence and so it would transpire on May Day 1886 at the McCormick Harvesting Machine Company in Chicago.

On 3 May, workers were picketing the factory gates in a dispute that had been rumbling on for months. The atmosphere that was already tense turned to anger when a police cordon was formed to allow strike breakers to enter the factory. In the scuffles that followed a worker was killed and several others seriously injured. The strikers blamed the violence on police brutality – after all, it wouldn’t be the first time.

The Union leadership hastily organised a rally to protest the behaviour of the police to take place the following day in Haymarket Square, a centre of commercial activity in the city.

The City Authorities fearing trouble had ensured there was a big police presence but as the day progressed it seemed as if their concerns were unfounded. The inclement weather and perhaps the fear of violence had seen fewer people attend than expected while the speakers themselves had failed to generate much enthusiasm. Indeed, it seemed as if the entire event was a damp squib. As night began to fall the mayor who had been closely monitoring proceedings departed satisfied it had passed peacefully. Not long after his departure however, and in direct contravention of instructions received a senior police officer ordered the crowd dispersed. As the police closed in batons drawn fighting broke out. As the violence escalated someone threw a bomb into the police cordon. It exploded killing seven police officers and wounding sixty others, a further officer would die later of wounds received. In response the police fired into the crowd. In the gathering gloom some of the protesters who were also armed fired back. Chaos ensued as the Haymarket was turned into a war zone with people trampling others underfoot as they fled the scene. The police, meanwhile, no less frightened, seemed more inclined to revenge than they were restoring order.

In the immediate aftermath of the riot, it was reported that four demonstrators had been killed but a reporter for the Chicago Herald who had been present at the scene declared he had counted at least fifty dead lying in the street.

The police were quick to round up the usual suspects, the anarchist and socialist agitators who were always behind such events it seemed, and they weren’t wrong. It was anarchists who had organised the demonstration in the Haymarket and had distributed the fliers publicising it, some appeared to promote violence. August Spies, editor of the German language newspaper Arbeiter Zeitung (most of the strikers were immigrants from Germany) complained and the more aggressive fliers were withdrawn, but the damage had already been done.

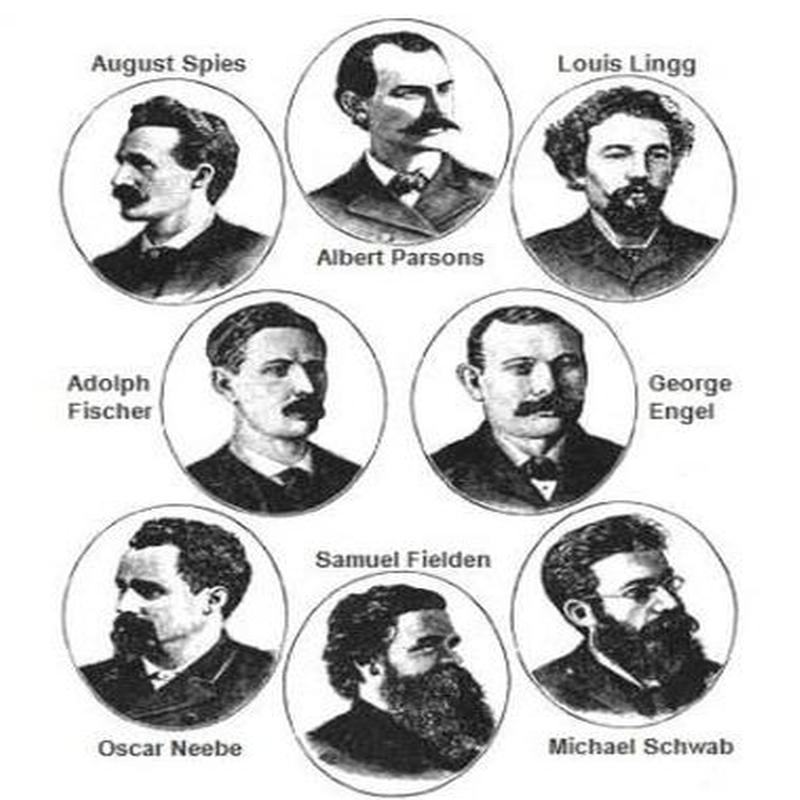

Despite the best efforts of Spies and others not to provoke confrontation in the days following the demonstration they were to be blamed for the violence and arrested for inciting it. Those now under lock and key were for the most part of German descent and all had connections to the anarchist or socialist movements. They were August Spies, George Engel, Adolph Fischer, Louis Lingg, Oscar Neebe, Michael Schwab, Albert Parsons, and Samuel Fielden. The charges laid against them would soon be upgraded to include that of murder.

Little evidence was produced that linked any of the accused directly to the violence let alone the making or throwing of the actual bomb; rather, the prosecution’s case rested on eyewitness testimony and the premise that these were dangerous, bad men. Spurred on by a hysterical media and the fevered imagination of the majority population a guilty verdict was perhaps inevitable regardless of evidence.

The trial which was conducted in an atmosphere of heightened excitement and often descended into chaos found all the defendants guilty of murder and sentenced them to death apart from Oskar Neebe who cleared of the most serious charge received fifteen years imprisonment.

There was an immediate and predictable outcry from the labour movement and liberal elites outraged not so much at the convictions as they were the harshness of the sentencing.

The convictions were appealed first to the Illinois State Supreme Court and then to the Supreme Court of the United States both of which upheld the sentence of death - hardly surprising given the intensity of feeling nationally against the accused.

It was clear to most people that the sentences passed did not bear out the evidence produced but sympathy was at a premium. Nevertheless, in November 1887, the Illinois State Governor Richard Oglesby commuted the death sentence passed on Michael Schwab and Samuel Fielden to one of life imprisonment.

On the night before his execution Louis Lingg placing a small explosive device into his mouth that had been smuggled into his cell earlier, exploded it. It destroyed much of his face but still he lived for a further agonising six hours.

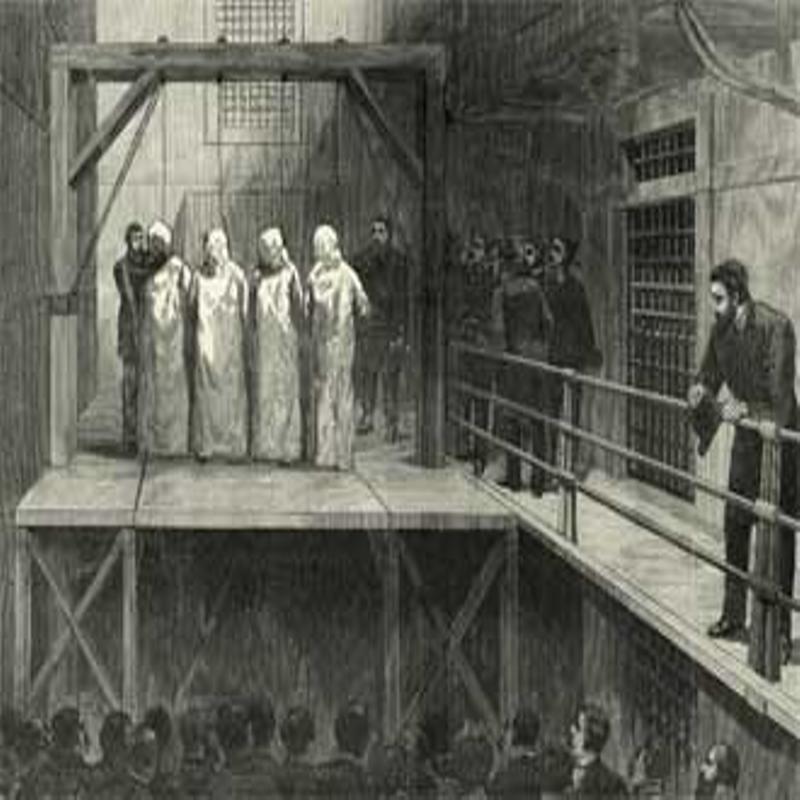

On 11 November, Spies, Engel, Fischer and Parsons were led to the gallows. Already hooded they shouted their defiance, nonetheless. August Spies last words were reported to have been: “The time will come when our silence will be more powerful than the voices you strangle today.”

It was not a quick death - no necks were broken by the drop. Death was by slow strangulation. Those who witnessed the spectacle were not impressed by it.

The Haymarket riot was one of many labour disputes that turned violent during the fast-track industrialisation that swept the United States in the late nineteenth century. It, along with mass immigration produced the ‘Red Scare’ that would dominate American politics for many decades. Combined they fuelled the fire of paranoia that led to increased violence, deportation, miscarriages of justice, and revenge attacks.

Following the events in Chicago membership of the Knights of Labor decreased sharply and by 1890 it stood at barely 100,000. Its reported involvement in the Haymarket Riot had cost it dear. It helped little that in June 1893, the new Governor of Illinois Peter Altgeld pardoned Neebe, Fielden and Schwab. The four hanged were given no such consideration.

Tagged as: Modern

Share this post: