The Legion of St George

Posted on 25th September 2021

During World War Two 321,559 non-German nationals are known to have fought for the Nazi's. They were volunteers many of whom had enlisted in the various SS Viking Formations. Of these some 50,000 came from the Netherlands, 25,000 from the Ukraine, 23,000 from Belgium, 8,000 from France, 6,000 from Norway, and 59 from Britain.

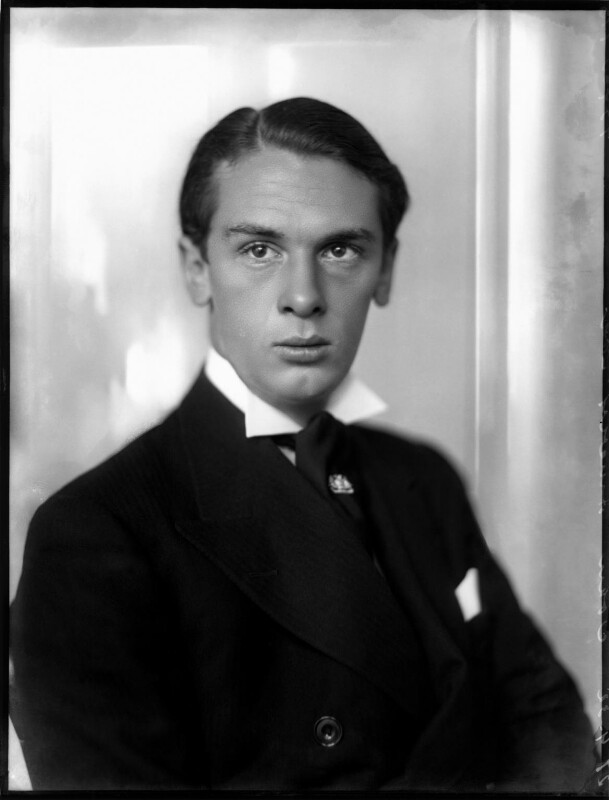

The idea of forming a British Free Corps from among prisoners-of-war who might with a little prompting be persuaded to betray their country and fight for the Germans was the brainchild of the Old Etonian John Amery, the son of the Cabinet Minister, Leo Amery and brother of the Conservative Member of Parliament and fighter pilot, Julian Amery.

John had always been the runt of the Amery litter. Never able to hold down a proper job he was always going cap-in-hand to his father for money, and he was to alienate his family even further when aged 21, he married the former courtesan and well known gold-digger, Una Wing. Unable to maintain his new wife in the lifestyle she both expected and demanded in 1936 he was declared bankrupt and fled to France to avoid his creditors. He and Una separated soon after.

He had long been fascinated by the doctrines of National Socialism and whilst in France he made the acquaintance of leading right-wing politicians including Jacques Doriot, the leader of the fascist Parti Populaire Francais (PPF).

Trading on his name as a means of remuneration and claiming that he had contacts with leading political figures in Britain he enhanced his pro-fascist credentials further by awarding himself a medal. It was in fact a less than convincing piece of extravagant costume jewellery that he claimed he had earned fighting for Mussolini's Italian Fascist Volunteers in the Spanish Civil War. He had in fact never even visited Spain and it fooled few people.

After France was overrun in 1940, Amery remained in the Vichy Zone but soon became disillusioned feeling that Petain's collaborationist regime was simply not fascist enough and it was Doriot who suggested that he travel to Berlin and pitch his idea of recruiting an army from among British and Commonwealth prisoners-of-war to fight on the Eastern Front.

In September 1942 he travelled to Berlin where he was granted a personal audience with Adolf Hitler. The Fuhrer was impressed with this educated, erudite Englishman with the cut-glass accent granting him both permission and funds to embark upon his recruitment drive.

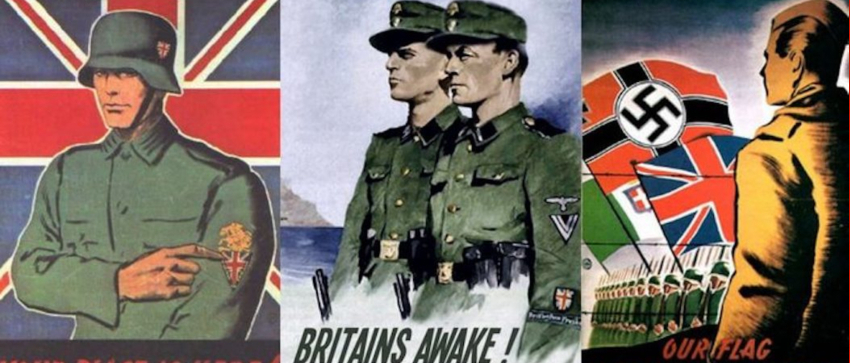

A delighted Amery decided to call his new army by the rather grand name, The Legion of St George and he threw himself into his work with a commitment he’d never shown previously in his life. He produced and distributed literature throughout the camps and visited several of them himself where he personally addressed the troops. His message did not go down well and neither did he with his upper-class voice and shrill almost hysterical tone.

Men who had put their lives on the line in the service of their country were not impressed by this man of privilege telling them that they should betray their homeland and he was dismissed as a pitiful even laughable figure. For all his effort Amery was to recruit just two men, only one of whom, Kenneth Berry, would ever go on to join the British Free Corps.

Not long after Amery was dismissed from his role and instead given the task of broadcasting for the Nazi's. The recruitment drive would continue, however.

The Germans established two "Holiday Camps" as they were known for those British and Commonwealth troops who had responded positively to the propaganda and seemed likely recruits. These Camps named Detachments 999 and 517 were run by English speaking guards. What they needed however was a Briton who could act as an intermediary and effective recruiting agent, and they believed they had found one in Sergeant John Brown of the Royal Artillery.

Brown had been captured at Dunkirk and prior to the war had been an active member of the British Union of Fascists. He appeared the ideal choice, respected by the men and ideologically sound. They could not have been more wrong. Regardless of his political affiliations Brown was no traitor and he used his position of privilege to gather intelligence which he then relayed back to England. He also used his new role to gather contraband which he distributed to the troops in the Camps.

Thomas Haller Cooper was a very different man, however. Like Brown he had been a member of the B.U.F. but he was a true believer and had travelled to Germany to experience National Socialism for himself. When war broke out rather than return to Britain to be conscripted into the Army he remained in Germany and enlisted in theirs and he was to be the only British national to be awarded a German Service Medal during the war.

Cooper's task was to visit the Camps and convince the prisoners of the benefits of fighting for the Germans instead he regaled them with was stories of the atrocities he had committed against the Jews and Soviet prisoners-of-war.

He and Roy Courland, a vehemently anti-Communist New Zealander who had been captured in Greece toured the Camps trying to recruit those with right-wing sympathies whilst reporting on those who expressed the opposite. This caused a great deal of resentment and in one Camp they were almost lynched with a senior British Officer having to be called in to calm the situation.

Despite their best endeavours the idea of recruiting an ideologically committed British SS Division was not going well. By December 1943 they had still only recruited 8 members.

It seemed that those troops who volunteered to attend the "Holiday Camps" were happy enough to attend classes, listen to the propaganda, accept the plentiful supply of cigarettes and coffee on offer and eat the ample food provided but had no intention of signing up for anything. A more aggressive policy needed to be adopted and Cooper decided to focus his attention on the recently captured who he believed would be nervous, afraid, confused, vulnerable and more easily manipulated. These men would be isolated from other prisoners, be stripped naked and forced to endure sleep deprivation, blackmail, bullying, and outright intimidation. But even so he was little more successful.

On 1 January 1944 the British Free Corps at last came into existence but they’d had to reduce their ambitions from the thousands they had originally hoped to recruit. It was now decided that once the volunteers numbered 30, they would be deemed a Combat Unit and be assigned to a Panzergrenadier Division where they would be commanded by a German Officer and have to swear an oath of loyalty to the person of Adolf Hitler.

As members of the SS, they would not have to carry the blood tattoo but they would receive the same wages as German troops. They would also wear the standard SS uniform but with a Union Jack embroidered on the right sleeve.

Following D Day on 6 June 1944, many of those who had joined the British Free Corps began to see the writing on the wall and some who had supposedly been committed to the cause such as Courland and Sergeant Frank MacLardy, who had been a B.U.F First Secretary back in England now, sought transfers to non-combat units.

Others such as Eric Pleasance from the Channel Islands, who would later claim that he had only joined to have a good time, and Private John Wilson who simply thought it would give him the opportunity to meet women couldn't get out quick enough.

Once it seemed that the total of recruits was about to hit the magic 30, some feigned illness while 14 others requested to be sent back to the Camps.

At the end of the day the British Free Corps never fought anyone and whilst foreign recruits did the Germans dirty work on the Eastern Front, Dutch SS Divisions opposed the Allied advance from Normandy, and the 2,185 strong French Charlemagne Division were to be among the last troops fighting in the rubble of the Reichstag, they never so much as fired a shot in anger. German attempts to recruit a British SS Division had turned out to be a damp squib. When they did at last recruit a British Officer, he turned out to be a paranoid schizophrenic and was later repatriated back to England.

But there didn’t exist in Britain that strain of political fanaticism that had infected so much of the European Continent between the wars. Fascism had never taken hold in the world’s oldest democracy where the thought of single-party rule or blind devotion to the person of one man was simply anathema.

Only 72 British and Commonwealth soldiers ever agreed to join British Free Corps and it membership peaked at 27. In the main those who joined were freeloaders who when they were returned to the Camps were ostracised by their fellow prisoners who heartily disliked them and were disgusted by their activities.

They may have been poor specimens of humanity, but MI6 had a file on every one of them.

Thomas Haller Cooper was captured at the end of the war returned to Britain where he was tried for treason. Found guilty he was sentenced to death, but this was later commuted to life imprisonment of which he served 15 years.

Roy Courlander rather than fight fled to Belgium where tearing off his B.F.C insignia he surrendered to the first Allied soldiers he encountered. He too was tried for treason and sentenced to 15 years imprisonment of which he served 7. He later returned to New Zealand where he died in poverty.

Frank McLardy was sentenced to life imprisonment reduced to 15 years of which he served the full-term.

John Wilson, who had only joined the B.F.C so he could get drunk and chase girls, was sentenced to 10 years in prison.

Kenneth Berry, who had been captured as a 14-year-old deck hand when his ship had been sunk and had become the first recruit to the B.F.C was sentenced to just 9 months confinement. He had expressed his regret at having participated and his young age had been taken into consideration.

All the other members of the British Free Corps except for Sergeant John Brown and a Private Freeman who was also able to prove that he had only joined to try and undermine the Unit and so was cleared of all charges, were given sentences of varying degrees of leniency.

The British Government embarrassed that there had been those who had been willing to take up arms against their fellow countrymen simply wanted the brush the episode under the carpet. In most other countries they would have faced execution as traitors.

One man who did face the prospect of execution however was John Amery.

Thin, frail, and intoxicated he had been captured in Italy at the end of the war and returned to Britain where he was tried for High Treason. His high-profile and politically influential family, appalled and humiliated by his behaviour, now abandoned him.

Resigned to his fate he surprised everyone when he offered no defence and pleaded guilty to all charges. At the end of the proceedings which lasted only 8 minutes, he was sentenced to death. He was hanged at Wandsworth Prison on 19 December 1945. Shaking the hand of his executioner Albert Pierrepoint, he remarked that it was a shame they could not have met under better circumstances.

Pierrepoint was later to say that he was the bravest man he ever hanged.

Share this post: