The Lost Legions: Massacre in the Teutoburg Forest

Posted on 7th October 2021

After decades of civil war both before and in the immediate aftermath of Julius Caesar’s assassination, Rome was at last at peace under its new ruler Octavian. He was the nephew and adopted son of Caesar who had seized power for himself following the defeat of his co-ruler and rival Mark Antony at the Battle of Actium in September 33 BC and his subsequent suicide along with that of his ally Queen Cleopatra of Egypt in Alexandria a few months later.

On 16 January 27 BC, the day the Roman Republic ceased to exist he had himself crowned Emperor and was awarded the title of Augustus by a grateful Senate.

Octavian’s usurpation of power in Rome did not cause the political turmoil that might normally have been expected for after years of instability and war people wanted nothing more than peace, order, and most of all prosperity. Now as Augustus and Rome’s first Emperor, Octavian would provide this and under his guidance the city thrived as never before.

In the years that followed it was to become the commercial centre and powerhouse of the known world, the very hub of civilisation while also busily extending the borders of its Empire. The early decades of Augustus’s reign were a period of unprecedented conquest with Egypt, modern day Spain, Switzerland and much of the Balkans being added to the burgeoning Roman Empire. It was wealthy, confident, strident, arrogant and indestructible. But all this was to change on a late autumn day in a distant, cold, dark, wet, fog-bound, and forbidding German forest.

For many years Rome had been engaged in wars on both its western and eastern frontiers as it sought to expand its Empire and as a result its Legions were often stretched and any shortfall in their numbers were often made good by foreign volunteers or captives pressed into service. One of these was Arminius, a German of noble birth from the Cherusci Tribe who had been commanding a unit of Cheruscan cavalry campaigning in the Pannonia region of the Balkans.

He had been brought to Rome as a child having been taken hostage to secure the future good behaviour of his father, Segimenus. Raised as a Roman he prospered, attained citizenship, and even rose to the rank of Equestrian thereby becoming a member of the lower-nobility and though of foreign birth could now demand that he be addressed as, Sir.

Arminius had made a formal request to be posted back to Germania but there had been a whispering campaign against him for some time from those who thought him to be ambitious beyond his status.

But despite doubts having been raised regarding his loyalty no evidence had been produced and so when these doubts were put to Augustus, he dismissed them as being mere tittle-tattle. After all, Arminius had been a good soldier and he appeared as Roman as any one of them. In AD 8, Augustus gave permission for Arminius to return to the region of his birth.

It had only been in the last ten years that the Romans had dared to venture north of the river Rhine, during that time however they had met little resistance and had annexed a great deal of territory. The seeming compliance of the local tribes made them think it was the time to begin the process of Romanisation and create a profitable province, a place that could be properly taxed and exploited. The man charged with implementing the changes was its new Governor, Publius Quintilius Varus.

Varus was neither a politician nor a soldier by profession but a lawyer. He had nonetheless previously been Governor of Syria where despite his well-documented greed he had maintained a steady flow of tax revenue into the emperor’s coffers in Rome. More significantly perhaps he was married to Augustus’s great niece Claudia Pulchra and so was family. To an Emperor still wary of his position even after so many years in power this was important, and his policy remained to appoint relatives to positions of authority if possible; but such a policy was often carried out at the expense of competence and Varus was a man who was not only rapacious, vain, and cruel but insensitive and complacent.

He also had no love of Germania, a place described as being little more than a fearful forest and a stinking bog. Nor did he care for the filthy and ignorant wild men who inhabited it. He would exploit them for all they were worth and if they resisted then the punishment would be harsh.

Charged with opening trade, co-opting the local tribes, collecting tax, and establishing outposts of civilisation in hostile terrain he lacked both the military expertise of a soldier and the guile of a diplomat. Indeed, preposterously arrogant he alienated most of those he was supposed to encourage to accept and co-operate with Roman hegemony. The historian Cassius Dio wrote:

“When Qunitilius Varus became Governor of the province of Germania and in the exercise of his powers also came to handle the affairs of these people he sought to hasten and widen the process of change. He would not only give orders to the Germans as if they were slaves of the Romans but levied money from them as if they were a subject nation, these demands they would not tolerate.”

Upon his arrival in Germania, Arminius was quick to befriend this new Roman Governor, and Varus quickly became reliant upon Arminius as the commander of his German cavalry for both intelligence and local knowledge.

Frustrated by the failure of so many of the tribes to fulfil the quota demanded of them in tax, Arminius convinced Varus that only his personal presence in the tax collecting process would lend it the necessary authority to convince the recalcitrant tribes to pay up. So that summer, Varus set off on a punitive mission to teach the tribes a lesson.

How exactly Arminius convinced Varus to take his entire army with him on what was essentially a simple tax collecting mission remains a mystery.

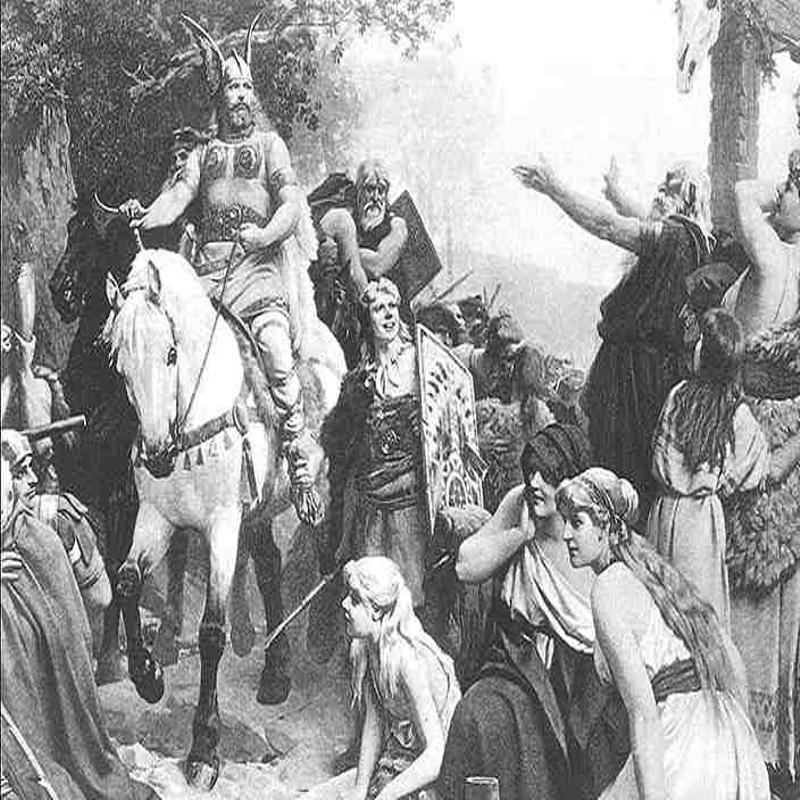

Arminius had long harboured ambitions to break free of the Roman yolk and in the previous months, using his native name Hermann, had been busy forging an alliance of the Germanic tribes to resist Roman occupation. This was no easy task given that the German tribes were deeply suspicious of their neighbours and hated each other almost as much as they did the foreign invader. Nevertheless, by late September he had persuaded the Cherusci, Marzi, Chatti, Chauci, Bructeri, and Sicambri to support him.

In the summer of AD 9, Varus set out on his campaign to bring the German tribes into line with three Legions, around 20,000 men, 5,000 mercenary troops, and a similar number of camp followers: “They had with them many wagons and pack animals as they would in peace time, and they were even accompanied by women and children including a large retinue of servants.”

The summer campaign had not gone as well as expected with so many of the tribes simply deserting those villages that lay in the Romans path and by late October his army was marching to winter quarters on the Rhine when Varus received a message from Arminius that persuaded him to divert course into the Teutoburg Forest. It seems likely that Arminius aware of the Governor’s greed had informed him that great wealth lay within his grasp for taking such a decision with winter setting in it was a poor military decision and one taken against advice.

The Romans ventured into the Teutoburg Forest with trepidation for it was a dense, dark place shrouded in fog with visibility poor and uncertain where they were going and what they might encounter as a superstitious people they feared the unknown. Their fears were further enhanced when soon after the Roman army entered the forest Arminius disappeared taking his Cheruscan cavalry with him.

Not only was the terrain unknown to them but now they had lost their eyes and ears, and no one knew where Arminius had gone, or indeed why he had gone.

The Romans were right to be fearful for not only were there few clear paths but much of the forest was so densely wooded that they were forced to cut a way through. It was exhausting work and progress was painfully slow as wagons became stuck in the mud, others overturned and could not be righted, and soldiers disappeared into deceptive and treacherous bogs never to be seen again. The column soon became so strung out that it was said to have stretched for more than ten miles.

As the column advanced further into the forest the attacks upon it began and though he was outnumbered the length of the column meant that Arminius was able to bring superior forces to bear at any given point.

Varus, who was travelling blind at the head of his troops because he had neglected to send out any reconnaissance units had also lost contact with the rear of the column and was unaware that they were already involved in a life and death struggle.

The attacks were relentless as the Romans unable in the conditions to form up for battle tried to fend off those assailing them from the woods as best, they could. Three days into the march Varus at last stumbled across a clearance big enough for a fortified camp to be hastily constructed and his exhausted men were able to get some respite, but it was to be brief.

As the night drew in messages began to reach him that those further down the column were under attack and it must have been now that he realised Arminius had betrayed him. At last, aware of the precariousness of his situation Varus planned a breakout from the camp in the hope of forcing the Germans into a battle where superior Roman discipline could be brought to bear.

But being raised in Rome and having fought so many years in their army Arminius knew the Roman mind-set well. He and his men were ready and prepared for any assault.

Unable to form up in their usual way the Roman attack made little headway and in the desperate hand-to-hand fighting that ensued the ferocious Germans were to prove more than a match for their Roman enemy.

Forced to retreat to their camp and having been unable to defeat the Germans in battle the decision was made to attempt a night march. They had to escape the forest as quickly as possible that was clear but all the time stragglers from the column arriving in camp regaled them with stories of German atrocities. The sense of fear was palpable, and many wanted to remain in camp to take their chances in daylight and in a place that at least afforded them some protection.

As soldiers tried to shelter from the rain and keep their weapons dry, they could be heard praying to the Gods and cursing Varus for his incompetence and blaming his greed for their predicament and their likely doom.

By the time the night march was ordered the baggage train laden with months of booty, now valueless, had already been abandoned as an encumbrance. Secrecy was essential to the success of the march and so soldiers were ordered to remain silent, anything that could make a noise was tied down and the bells around the necks of mules were stuffed with straw.

The weather however was foul and torrential rain had made many of the Romans arms unusable, especially their bows and shields but even their swords were by now blunted with rust. Nevertheless, the night march went ahead but there was no prospect of secrecy as every move was already being monitored from the forest and hills above them.

The attacks continued as stragglers were picked off and isolated units surrounded and wiped out their death screams echoing off the trees while the howls of derision from their assailants tormented those still stumbling around in the dark fearful that they would be next.

But there would be no salvation for Varus was advancing straight into the trap Arminius had set for him. By daybreak on 9 October, the Romans had reached a place known as the Kalkriese. It was a wide area of open space that was greeted with some relief by the Romans for it would at least give them the opportunity to manoeuvre but it had been carefully chosen by Arminius.

Enclosed by a densely wooded hill on one side, where Arminius had positioned most of his men, and an impassable swampland on the other it had only one path through it and Arminius had earlier constructed a series of walls that would funnel the Romans into an area less than a hundred metres wide. It squeezed them like a vice.

The Romans desperately tried to storm these fortifications but were unable to do so. Witnessing the failure of the Roman infantry Varus’s second-in command, Numonius Vala led his cavalry from the field abandoning the army. Vala’s treachery did not save him, and he was later ambushed and killed along with most of his men but it was to signal the end.

Observing the desertion of their cavalry discipline began to break down and Arminius seeing the disarray in the Roman ranks seized his opportunity.

He ordered an all-out attack and under ferocious assault the Roman Legions by now fighting in small groups or as individuals simply disintegrated. Aware that all was now lost, Varus and his Senior Commanders took their own life.

The defeat of the Roman Legions was total with some 20,000 killed and many others taken prisoner. Those Romans who could be identified by their insignia as Officers were buried alive as a sacrifice to the German Gods or were ritually slaughtered on specially made altars. Other prisoners were confined in wooden cages that were then set alight. The women and children were mostly spared to become slaves but only after severe beatings had been administered and the women had been defiled and raped.

The massacre in the Teutoburg Forest was to shake Rome to its very foundations.

The thought that their armies could be so utterly destroyed by barbarians was unthinkable and it displayed a vulnerability that had not been exposed since the days of Hannibal almost a hundred years earlier. The three Legions that had been lost in what became known as the Varian Disaster amounted to fully 10% of the entire Roman Army and the Emperor Augustus was in a state of shock. The historian Seutonius wrote:

“When the news reached Rome he (Augustus) ordered patrols of the city at night to prevent any uprising. It is said that he took the disaster so deeply to heart that he left his hair and beard untrimmed for months. He would often beat his head on a door and be heard to cry “Quintili Vare, legions redde! – Quintilius Varus, give me back my legions!”

Augustus ordered his adopted son Tiberius to Germania to stabilise the situation.

Tiberius was a competent if unimaginative General but he was an able administrator and with great difficulty he was able to secure Rome’s borders on the Rhine.

In the meantime, Arminius despite the glory of his triumph was struggling to forge a permanent alliance of the Germanic tribes but he was unable to convince King Marbod of the Marcommani, by far the largest and most powerful of them, to join him. Marbod was jealous and he would not be seen to subordinate himself to the upstart Arminius despite having been sent the head of Varus as a gift.

On 14 September, AD 14, the 78-year-old Augustus died to be replaced as Emperor by Tiberius. Early the following year Tiberius sent his nephew Germanicus with an army as many as 100,000 strong to bury the dead in the Teutoburg Forest and launch a furious assault upon the German tribes.

The historian Tacitus tells us of what Germanicus discovered in the forest:

“On the open ground were whitening bones scattered where men had fled, heaped up where they had stood and fought back, fragments of spears and of horses limbs lay there, human heads were fastened to tree trunks, and in groves nearby were the elaborate altars where the Germans had massacred the Colonels and Senior Commanders.”

Germanicus was to be true to his orders as hundreds of villages were burned and destroyed and thousands of men, women and children massacred or sold into slavery. Arminius however fought back and despite the overwhelming forces at his disposal Germanicus was never able to fully quell the German tribes. He did capture Arminius’s pregnant wife Thusnelda however, who was handed over to him by her father who was jealous of and feared Arminius.

She was taken back to Rome to be paraded naked through its streets in chains before a howling mob baying for vengeance as her father looked on.

Thusnelda was never seen in public again though it is believed she gave birth to a son named Thurnelicus who later fought as a gladiator in the arena.

By AD 16, Germanicus was back in Germania this time invading it from the north. He won several major battles, but Arminius was always able to rally his men and soon began inflicting defeats on the Romans as much to their frustration following any battle the Germans would melt back into the forest somewhere the Romans were understandably reluctant to follow.

At one battle on the Wieser River, Tacitus describes how Arminius hailed his brother Flavus who was fighting for the Romans and begged him to return to his homeland and his people. Flavus in turn demanded his brother give himself up saying the Romans were firm but fair and he would be forgiven:

“So what do you get for being a slave of the Romans?” asked Arminius.

“More money and a promotion,” replied Flavus.

Neither convinced the other.

Despite bringing superior forces to bear and carrying out terrible acts of vengeance Germanicus had failed to conquer the Germanic tribes or achieve the strategic victory that was expected of him but was nevertheless awarded yet another Triumph which provoked Tacitus to acidly remark: “The Germanic tribes were more triumphed in Rome than defeated in Germany.”

Germanicus may have failed in his mission but so ultimately would Arminius. His attempt to create a permanent alliance of Germanic tribes was stymied by his conflict with Marbod who instead became his implacable enemy.

In AD 19, ten years after his great victory in the Teutoburg Forest he was assassinated by those among his own tribe who were jealous of his power. His most formidable foe Germanicus had himself been murdered two years earlier.

Despite Arminius’s failure to forge a nation from amongst the disparate and squabbling Germanic tribes, Rome never again tried to conquer Germania or extend its territories beyond the Rhine which would now form the northern most border of the Roman Empire.

As a result of their failure to pacify Germania much of Northern Europe was never subject to Roman rule. This would have huge implications for the future of European history creating a fault-line on the Continent that was to be the cause of future conflicts and remains so to this day.

Tagged as: Ancient & Medieval, War

Share this post: