The Mayerling Incident: A Habsburg Tragedy

Posted on 24th January 2021

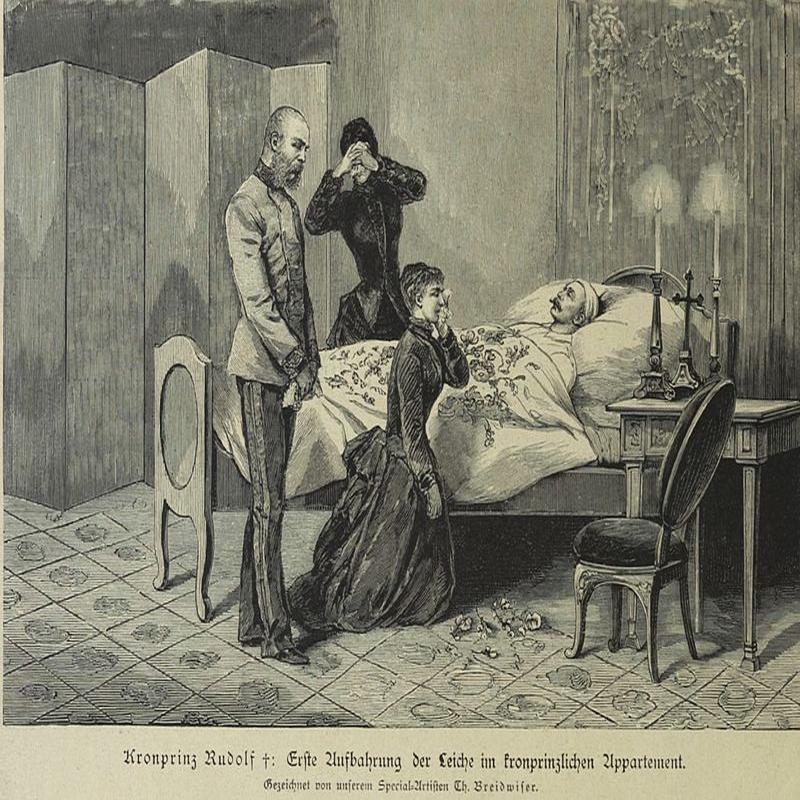

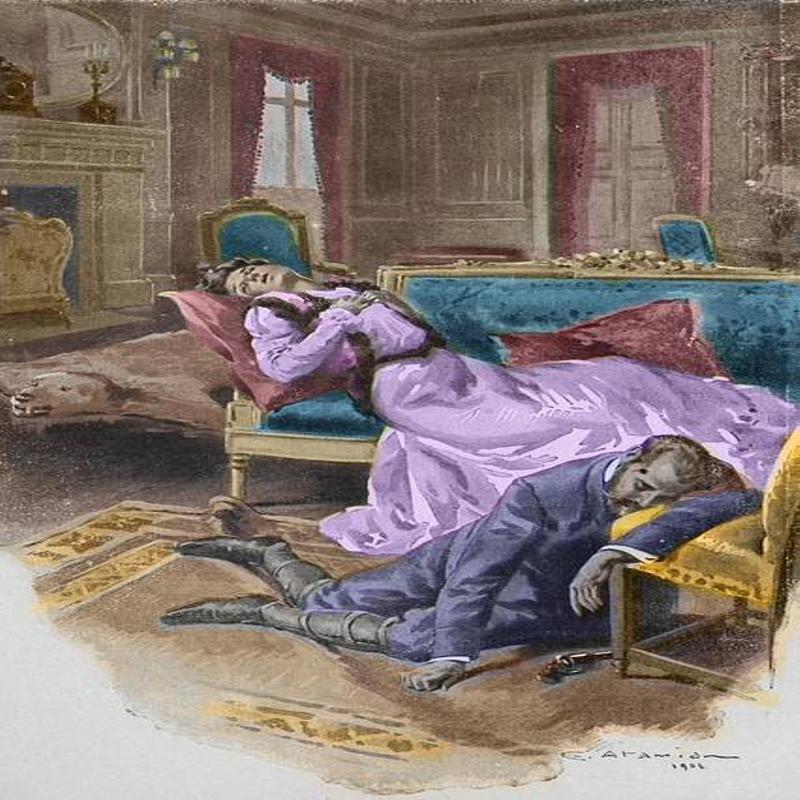

Early on the morning of 30 January 1889, in an isolated Hunting Lodge at Mayerling deep within the Vienna Woods the body of Crown Prince Rudolf, heir to the throne of the Austro-Hungarian Empire was found slumped in a chair dead, before him on a table was a mirror and a glass, blood was still seeping from his mouth. Stretched out on a nearby bed was the pale, cold, and lifeless body of his 17-year-old lover, Baroness Marie Vetsera.

The Hunting Lodge was immediately sealed off and the body of Mary, as the Baroness preferred to be known was removed and taken away for burial. Indeed, she was interred in such haste that her family, though informed of her death, had no time to arrange the funeral let alone attend it.

The information emerging from the Mayerling was at first vague and confused. The prince’s valet who discovered the body reported that he believed poison to have been the cause of death, but the official communique announced the Crown Prince had died of heart failure. No mention of Mary was made in either account.

It is possible that the confusion was the result of an attempt to spare the feelings of the Imperial Family or a reluctance to reveal too much because of fears that it might create instability within the Empire. Either way, it was perceived to be a botched attempt at a cover-up which only served to sow suspicion and doubt.

People did not believe the official version of events, that a healthy 30-year-old man had simply died of heart failure and it appeared trite that a man so often as inconvenient as the Crown Prince should die such a convenient death. As journalists from across Europe descended upon the scene their investigations were to reveal what was at best a partial truth.

Slowly it emerged that the likely cause of the deaths was a double suicide, that the Crown Prince had shot the Baroness with her consent before sometime later turning the gun on himself. But why would they do this?

The Austro-Hungarian Empire even in the 1880’s seemed a place that was out of step with the modern world, its latent grandeur, many protocols and strict formality of the Imperial Court. The suffocating embrace of custom and ritual, the grand processions, the glittering balls and the dazzling display of exotically titled women and uniformed men all presided over by the venerable and be-whiskered figure of the Emperor Franz Joseph provided it with the image of a fairy tale land in the heart of Europe. But the myth was far removed from the reality and the Habsburg Empire had long been a ramshackle and shambolic structure struggling and on the brink of collapse.

This threat of dynastic extinction hung heavy like the Sword of Damocles and manifested itself in a fear of change so deep that when reforms did come such as the Augsleich of 1867 which resulted in Hungarian devolution and the creation of the Dual Monarchy they were invariably forced upon it.

Despite the Empire’s vulnerability its instinct remained one of oppression, a stark and divisive policy in a disparate, multi-ethnic Empire in which the Austrians themselves were but a small minority. Yet it survived and the glue which held it together was the person of the emperor - forty years on the throne and to him, and him alone could unambiguous loyalty could be sworn. Upon his death the responsibility for maintaining the Empire and the oldest dynasty in Europe would fall to his only son.

But the Crown Prince Rudolf was not his father, he did not share his politics, he did not feel comfortable shrouded in the cloak of His Imperial Majesty but instead felt stifled by it. He could not be relied upon, was aloof, undignified in his manner, discourteous to servants, and rarely it seemed sober - so unlike his devoted and hard-working father. The two men could not bear to be in each other’s company. He got on better with his mother, the Empress Elisabeth, but even she despaired at his behaviour and expressed concern at the company he kept.

He openly mixed in radical circles where he expressed views contrary to the policies of the Government both domestic and foreign. It was to see him, the future Emperor, effectively alienated from the decision-making process. They simply could not countenance the reforms he advocated: greater democracy, the reconstituting of Poland, his open hostility towards Russia and France and his belief that the Empire should distance itself from its closest ally Germany. To many his reforms if implemented would see the dismantling of the Empire itself.

This tendency to behave rashly and speak out of turn had long been evident as was his love for the seamier side of Viennese life, its cabarets, bawdy theatres, dancing girls and street prostitutes. This was unacceptable behaviour for the heir to the throne and both Franz Joseph and the Empress Elisabeth decided that he must be made to marry as soon as possible before he ruined himself and possibly also the Empire. But this was easier said than done however, as suitable Catholic Princesses of child-bearing age were far and few between.

Rudolf’s refusal to marry to any woman he found physically unattractive decreased the available options even further and being touted around the Royal Houses of Europe was not an experience Rudolf enjoyed but even in his most irrational and recalcitrant of moods he recognised that for the sake of the dynasty an appropriate marriage was essential, though when he was to come to choose his bride it was, initially at least, to be the cause of some embarrassment.

On 5 March 1880, Rudolf arrived as a guest at the Royal Court of King Leopold II of Belgium.

The Royal House of Belgium had been established less than 40 years and Leopold was eager to lend it greater legitimacy by forging a marriage between his 15-year-old daughter Princess Stephanie and the heir to the oldest Empire in Europe. Having already declined the hand of both the Spanish and the Portuguese Infanta Rudolf last appeared to have settled on his choice. He wrote to his mother with satisfaction rather than enthusiasm: I have found what I sought.

Elisabeth was less than impressed believing her son to have chosen a bride from a parvenu dynasty well below the status of a Habsburg but the emperor believing marriage would calm the Crown Prince’s troublesome soul was quick to endorse it.

Princess Stephanie was sent to Vienna to be instructed in Habsburg Court etiquette, but it was soon discovered that she had not even yet reached puberty. When she was told of what would be expected of her as a bride it became apparent that she had no understanding whatsoever of the facts of life. Much to everyone’s embarrassment she had to be returned to Belgium.

Nonetheless, the following year the marriage went ahead and for a short time at least it seemed as if the couple were happy but by the time Stephanie gave birth to their daughter Erszebet in September 1883, they had already begun to grow apart. The Princess Stephanie was not what Rudolf had been seeking after all, she had seen little of the world, was conventional in her views, and reactionary in her politics and she bored the excitable and highly-strung Rudolf whose interest in her soon waned both outside and inside of the marriage bed. He soon returned to his previous life of drinking and whoring late into the night.

Meanwhile Stephanie, ignored by the emperor and shunned by the Empress who considered her beneath them, was left in isolation to raise their daughter alone.

Mary Vetsera was only 15 years of age when she began her affair with the Crown Prince though to avoid scandal, always a priority of the Habsburg, their first meeting was officially declared to have been two years later.

At the time Rudolf was already in a relationship with the actress Mizzi Kaspar whom as the true love of his life he showered with money and gifts, and it was rumoured that he had already approached her with the proposal that they should join in a suicide pact. It was only after she had rejected the very idea as absurd that he turned his attention to the younger and more gullible Mary.

By now frequently drunk and increasingly outspoken some talked openly of him being bewitched by whores, and that he was an embarrassment to the Crown. He was also becoming a concern to the Habsburgs closest ally Germany.

Despite being beset by internal divisions and seemingly in terminal decline to Germany with a hostile France to its West and an always bellicose Russia to its East the Hapsburg Empire remained vital to its strategic interest and the German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck had not been shy in expressing his doubts regarding the Crown Prince, dismissing him as weak, emotionally unstable, and a dangerous man to have at the helm of a great Empire in the heart of Europe.

Despite being a distant second in the Crown Prince’s affections, Mary was nonetheless thrilled to have attracted his attention. Her family less so, they were ambitious no doubt but for their daughter to be the Crown Prince’s whore only to be discarded did little for her marriage prospects.

On 29 January 1889, Emperor Franz Joseph and the Empress Elisabeth gave a family dinner that Rudolf, much to their displeasure absented himself from on the grounds that he intended to leave early the following morning for his Hunting Lodge at Mayerling.

It was later rumoured that he had that morning argued furiously with his father over his request for a divorce from his wife that had been rejected out of hand. Not that Rudolf needed an excuse to absent himself from an Imperial Court he loathed. Unable to persuade him to remain Rudolf left in an ill-temper, there was little he did in good grace.

When he arrived at the Mayerling the following morning he found Mary was already there waiting for him, though he appeared indifferent to her presence. After a long night drinking and talking Rudolf retired to his bedchamber with Mary telling his valet Loschek to wake him in good time for a mornings hunting.

The following day unable to elicit a response from the Crown Prince and unwilling to force an entry on his own initiative Loschek informed Count Hoyos and together they broke down the door to the bedroom where they discovered outlined in the semi-darkness the dead bodies of the Crown Prince and his lover.

Even before the cause of their deaths had been ascertained Count Hoyos was on a train bound for Vienna where on his arrival he reported the news to the Emperor’s Adjutant-General Count Paar. After ordering Hoyos to speak no further on the matter he retired to ponder on exactly what to do. It was not his place he felt to inform the emperor of the tragic news but that it could only be done by the Empress and so he contacted the head of her household Baron Nopsca who in turn contacted her chief lady-in-waiting Countess Ida von Ferenczy upon whom the responsibility fell. By the time she at last summoned up the courage to inform her mistress of what had happened whispers were already being heard of tragic events and there was to be a further delay as Elisabeth broke down in tears at the news. She was unable to control her emotions sufficiently to tell the emperor for some time.

Reports of how Franz Joseph responded to the news of his son’s death vary from stoic resignation to seeming indifference. But then he was never one to express his emotions.

Little distracted by grief the emperor’s overriding concern seemed to be securing his dead son a Christian Catholic funeral. This could not be possible as a suicide and so a special dispensation had to be received on the grounds of his mental derangement at the time. The question of exactly how and why Crown Prince Rudolf and Mary Vetsera died at the Mayerling appeared secondary to the need for it to have been a good death, and as such still remains a mystery to this day: had they died in a suicide pact? Had Rudolf first murdered Mary and then killed himself? Had Mary been pregnant with his child and the murders committed to prevent scandal? Had they been murdered by agents of a foreign power?

Investigations appeared to suggest that Rudolf had apparently first shot Mary and then himself with a hunting rifle, a very difficult but not impossible thing to do. But if so, then why were the shots not heard? There are also no accounts of raised voices or any other disturbance.

Queen Victoria’s eldest daughter Vicky who had been married to the Emperor Frederick wrote to her mother of the incident:

I have heard things about poor Rudolf which may perhaps interest you. Prince Bismarck told me that violent altercations between Rudolf and his father had led to his committing suicide, but the Austrian Ambassador in Berlin tells me there had been no such scenes. The Chancellor (Bismarck) does not I think deplore it and did not like him.

Empress Zita, the wife of the last ruler of Austria-Hungary Karl, believed all her life that Rudolf and Mary had been murdered by French agents.

Rudolf’s death had changed the Habsburg dynastic succession and the line of inheritance now transferred to Franz Joseph’s brother Karl Ludwig who being of a similar age relinquished his rights in favour of his son Franz Ferdinand.

No more popular than Rudolf had been the future Archduke Franz Ferdinand was at least in every other way the opposite. He was stable, sober, and earnest but also understood the need for reform but not from any dreamy idealistic sentiment but for the sake of the Empire and its survival. But like Rudolf he would never inherit the throne and never get the opportunity to implement his ideas for it was his assassination in Sarajevo on 28 June 1914, that was to set the European powers on the path to war.

Tagged as: Miscellaneous, Monarchy

Share this post: