The Pilgrimage of Grace

Posted on 14th March 2021

By the autumn of 1536 it appeared that the great crises of Henry VIII’s reign were at an end; Katherine of Aragon was dead, Anne Boleyn had gone to the scaffold, the break with Rome was complete, the dissolution of the monasteries was well underway and the King’s pretty young wife was carrying his future son and heir - but things are not always as they seem.

Henry may have broken with Rome but many of his subjects had not, and certainly not those in the more isolated north of England far removed from the centre of power in London.

Discontent had been growing for some time, a series of poor harvests had seen prices rise while the passage into law of the Statute of Uses had abolished the device whereby landowners could avoid payments to the Crown by giving away their property to another on behalf of a third party (often the landowner himself or his immediate heir) which had dismayed much of the local gentry; but hardship was commonplace and rarely lead to the people rising in revolt against their Sovereign Lord. It was the King’s religious policy, his attack upon its institutions and in particular his dissolution of the monasteries, that would prove the final straw.

The Act of Supremacy of 3 November 1534 had declared Henry VIII, Supreme Head of the Church of England and was followed shortly after by the Treason Act which made denial of the Royal Supremacy punishable by death. Although he remained conventionally Catholic in his own religious belief and practice Henry exalted in being Supreme Head of the Church in England as he also did in the policy of his Chancellor Thomas More to dissolve the Monasteries and sell Church property which saw money flood into the royal coffers.

In the 1530’s there were more than 900 Religious Establishments besides Churches and Cathedrals employing around 1 in 50 of the total population and owning a quarter of all the landed wealth in the country. Much of that wealth would soon belong to the Crown and during Henry’s reign 625 monastic communities would be dissolved.

But many monasteries were central to the everyday life of local people providing a place of refuge, herbal medicines with which to treat a variety of ailments and alms to the poor aside from tending to the spiritual needs of their flock.

It has been suggested that Henry’s religious reforms had been too recent to have had much of an impact but for people to see their monastery stripped of its silver plate, its holy relics destroyed and its monks cast out before being closed down was a visceral and very real attack upon their way of life; the fact that the men who carried out these acts of vandalism were often reliably Protestant Huguenot refugees from the religious wars in France only alienated the locals further.

Henry would not countenance opposition to his religious reforms however, and when his Queen, the pregnant Jane Seymour, a devout Catholic fell to her knees and protested the closure of the Abbeys he referenced her recently departed predecessor, the beheaded Anne Boleyn, in response: “Get up, and do not presume to meddle in my affairs. Remember Anne.” She never mentioned it again and neither did anyone else in the Royal Court or on his Council.

The discontent of the people found its voice in the figure of a charismatic 36-year-old lawyer and Yorkshire landowner Robert Aske, recently returned from the Inns of Court in London who had at last found a cause worth defending in the religion of his youth.

The first indication of trouble occurred further south however, in Lincolnshire, when on 1 October 1536 people protested the dissolution of Louth Park Abbey preventing the Government Commissioners from carrying out their assignment. Encouraged by their success they now issued a series of demands including a return to the Old Faith, the protection of their Churches, the execution of heretics, and that ever-present in any protest, no new taxes in peacetime. The response when it came was in the form of a proclamation demanding that they disperse or be made to do so by the forces of Sir Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk. It is doubtful if Sir Charles had the means to enforce such an order but as it turned out the threat alone proved enough.

The disturbance in Lincolnshire may have passed off peacefully (though its leaders were later executed) but the discontent that had caused it remained, and a week later a more substantial rising erupted in Yorkshire that would not only continue to gather support but appeared to have an agenda that went beyond merely demanding that the religious reforms be reversed for they also threatened to march on London, purge the Royal Court of evil counsellors, and perhaps in time even depose the King himself – it became known as the ‘Pilgrimage of Grace’ and it could not be tolerated.

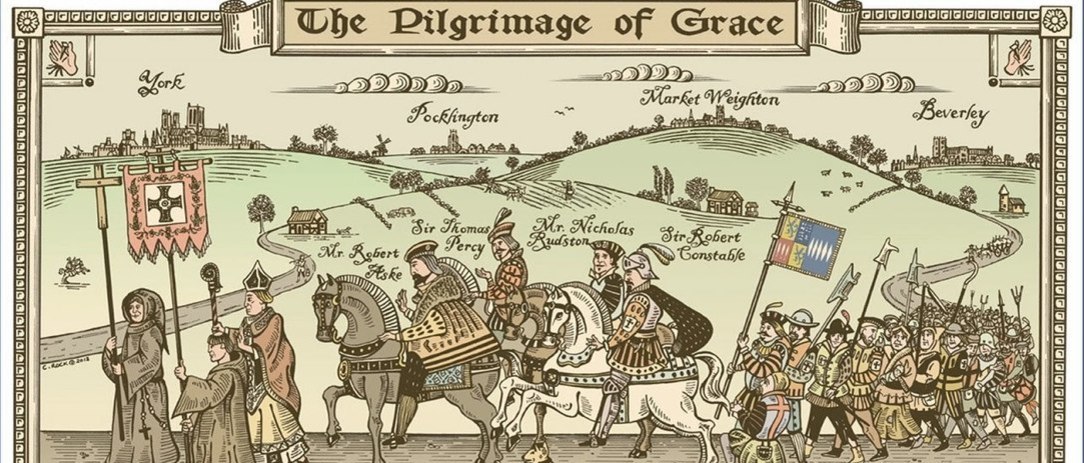

On 13 October, with Robert Aske at their head a crowd of some 10,000 people marched upon York and occupied it. In no time at all, the entire county and for miles around had rallied to his cause and he could soon call upon an army of 50,000 men all armed and willing to follow his lead. He also had the support of many local gentry some of whom had military experience and were to take positions of command.

But it was Robert Aske who led, it was he who provided the revolt with its ceremonial name the Pilgrimage of Grace and its banner of the ‘Five Wounds of Christ’ which the rebels not only carried before them but wore as patches on their clothes. In Durham Cathedral he addressed his followers:

“We intend to go to London on pilgrimage to the King, to have all the vile blood put from his Council and noble blood set up again, to have the faith of Christ and all God’s laws kept, and to have restitution for all the wrongs done to the Church.”

IIt was the most serious crisis of Henry VIII’s reign, and he reacted to it with firmness ordering Thomas Howard, Duke of Norfolk, to suppress the revolt immediately, but this was easier said than done. Even with the support of George Talbot, Earl of Shrewsbury, the Duke was only able to muster around 10,000 men and many of these had been drawn from the area now in revolt and could not be relied upon. He was unwilling to confront Aske under these circumstances and wrote to the King detailing his plight.

Henry broiled with frustration but unable to provide any immediate support he granted Norfolk permission to at least play for time and open negotiations with Aske. In the meantime, he would write in person to the rebels, first admonishing them for their disloyalty before adopting a more conciliatory tone and addressing some of their grievances:

“First, as touching on the maintenance of the faith we declare and protest our self to be he that always do and have minded to die and live in the purity of the same. Marvelling not a little that ignorant people will take upon them to instruct us, which something have been learn to be noted, what the right faith should be.

Concerning choosing of Counsellors I have never read, learned, heard, nor known, that a Prince’s Counsellors and Prelates should be appointed by rude and ignorant common people.

Wherefore we let you whit, ye our subjects of Yorkshire, to the intent that you all shall know what our princely heart rather embraces pity and compassion of his offending subjects than will to be avenged for their naughty deeds. That we are contented , if we may see all a sorrowfulness for your offences and will henceforth to do no more so, to grant until you all our letters patent of pardon for this rebellion.”

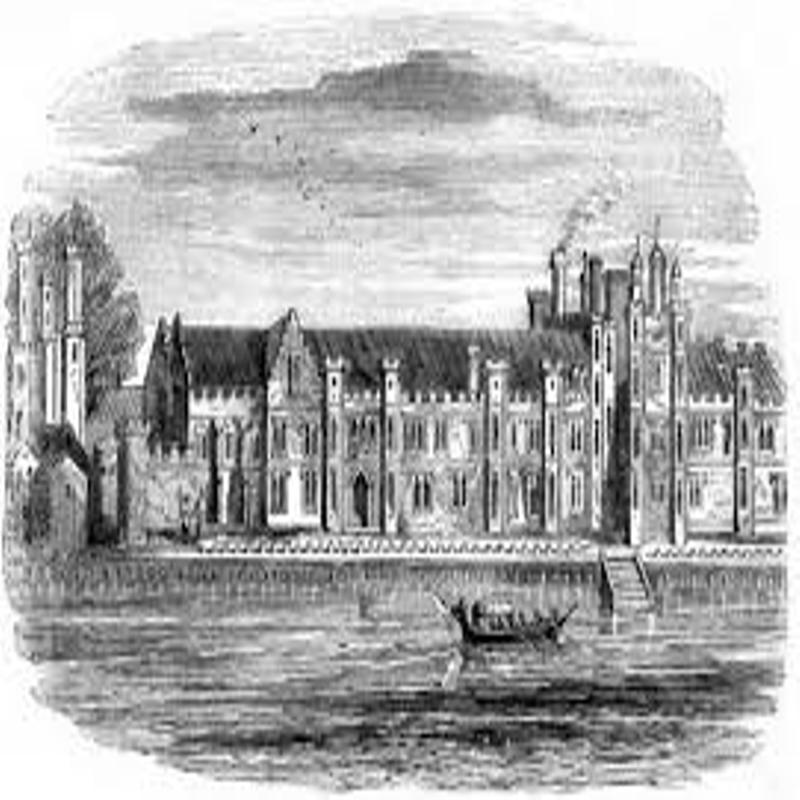

Following the receipt of the King’s letter on 13 November 1536, negotiations opened between Robert Aske and the Duke of Norfolk who repeated the promise of pardon to all who participated in the rebellion before agreeing that a parliament would be held in York to settle all grievances. He then presented Aske with the King’s invitation to spend Christmas with him and the Royal Court at Greenwich Palace. Flattered and no doubt a little in awe, he readily agreed.

During his brief stay in London Robert Aske was wined, dined, pampered and praised for both his sincerity and his resolve. He even received gifts from his host. In return he swore unswerving loyalty to the person of His Majesty the King. Aske returned north convinced of the King’s good grace and understanding. He reassured his followers that all would be well and that they could return home confident England would once again embrace the old ways.

In February 1537, a rebellion similar to that in Yorkshire and led by Sir Francis Bigod erupted in Cumberland and elsewhere in the north-west. They petitioned Aske for support but instead received a letter urging restraint:

“Neighbours, I do much marvel that you would assemble yourselves with Bigod seeing how earnestly the King’s Highness extended general pardon to all in this north. I hear you were forced to assemble by his threats and menaces, I shall declare this to the King, and fear not but that you will have his Grace’s pardon notwithstanding.”

Without Aske’s support Bigod’s insurrection in Cumberland was easily crushed and the repression that followed harsh regardless of promises made to the contrary; a lesson that seems to have been lost on Aske for when soon after he was invited once again to visit London he agreed; whether he did so with trepidation we do not know but it seems in hindsight to have been not just reckless but foolish to have done so. Seized upon his arrival he was taken to the Tower of London to await trial charged of treason.

The outcome of the trial was never in doubt and Aske knew it but whereas he could make his peace with God and reconcile himself to his own demise the means by which it was to be carried out filled him with dread. He wrote to the King begging to be spared the punishment reserved for traitors of being hung, drawn, and quartered. Henry, disturbed perhaps by his own duplicity relented but the means of execution devised in its stead was no less harsh.

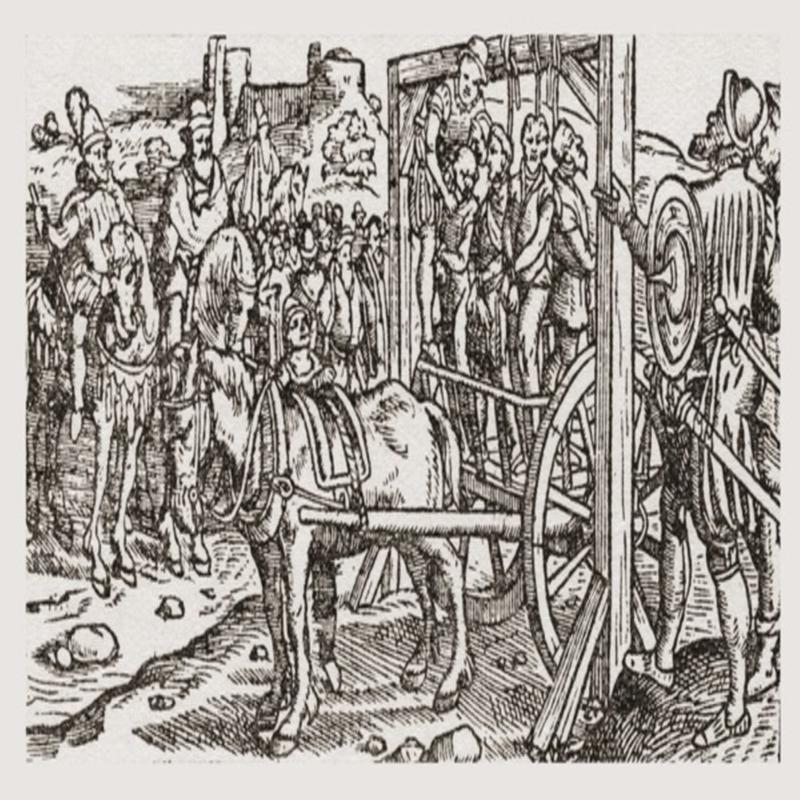

Robert Aske was returned to York where on 12 July 1537, dressed in rags he was tightly bound in chains and hanged from a scaffold on Clifford’s Tower where he was left to die an agonising death.

Having used the time bought in negotiations with the rebels to build up his own forces the King would now show no mercy. He wrote to the Duke of Norfolk:

“Our pleasure is that dreadful execution be done on a good number of the inhabitants of every town, village, and hamlet that have offended in this rebellion, as well as by the hanging of them up on trees as by the quartering of them, and the setting of their heads and quarters in every town great and small as there may be as a fearful spectacle to all others thereafter that may practice any like matter, which we require you to do without pity or respect.”

The Duke of Norfolk followed the King’s instructions to the letter and although exact figures of those who fell victim to the King’s vengeance remains unknown (in Bigod’s much smaller rebellion 216 people are recorded to have been executed) gibbets littered the Yorkshire landscape for many months to come.

Henry VIII’s brutal response to the Pilgrimage of Grace resulted from the threat it posed to his power and the Tudor Dynasty so established rather than from any religious conviction on his part. This would change when Henry died on 28 January 1547, to be succeeded by his nine-year-old son Edward VI, a devout Protestant under whom the Reformation would continue apace and become so firmly entrenched that even during the brief reign of his Catholic half- sister Mary little could be done to reverse it.

Tagged as: Tudor & Stuart

Share this post: