The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood

Posted on 18th September 2021

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was founded in the family home of the artist John Everett Millais in Gower Street, London, in the autumn of 1848.

Millais, along with his fellow artists Dante Gabriel Rossetti, William Holman Hunt and a little later James Collinson wearied by what they saw as the rigid formality and lacklustre attention to detail of the art being taught to students and emerging from the academies decided to adopt a fresh approach setting a series of ideals that they would seek to follow through both in their painting and their everyday existence.

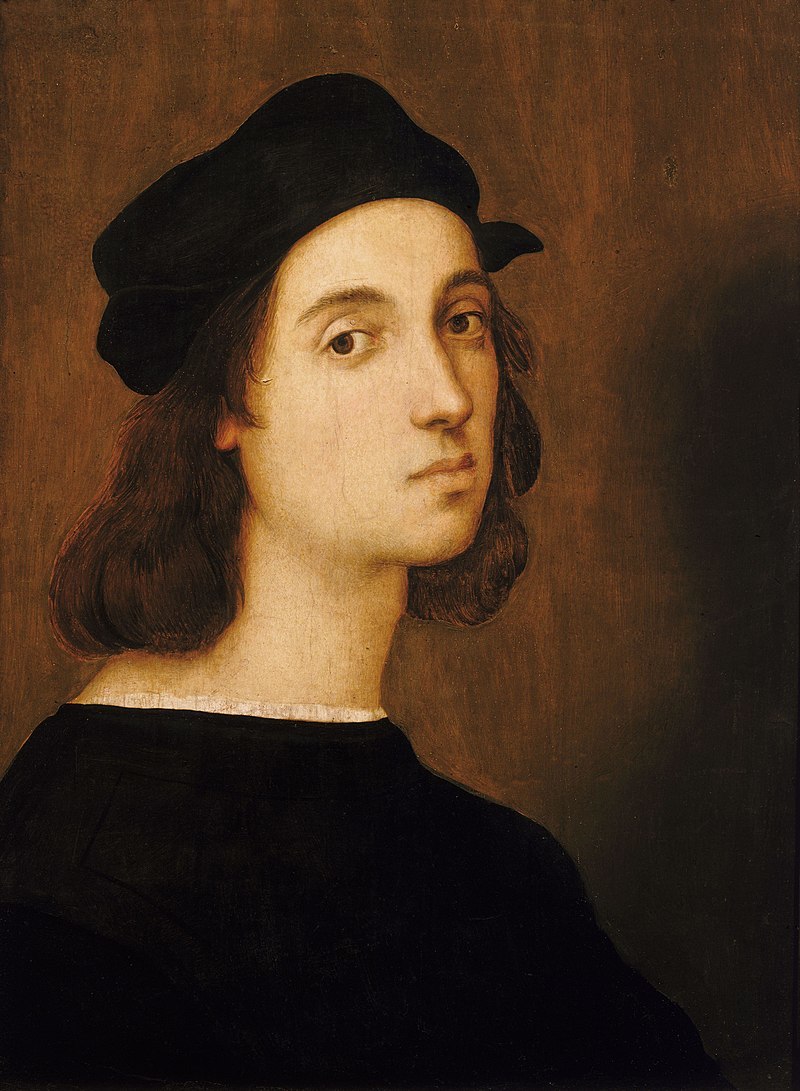

Believing the artist Raphael (1483-1520) to have corrupted their profession with his emphasis on the classical and the contrived and to have contributed little other than spawn a thousand imitators they named their movement the Pre-Raphaelite and as a Brotherhood they would seek to return art to its purest form.

There were to be few original ideas in content looking to history as they did for their inspiration but in context, technique, and form they were to be radical indeed, disavowing artists of a by-gone age for an emphasis on detail and the reality of nature in humanity and otherwise, where beauty emerged from the canvass and the thought committed the deed not the deed the thought.

It was in truth art as stylised as anything before or since, but it was still different, possessing an honesty of depiction that would prove controversial even within the parameters of the fantasy it created.

The temerity of these young men in believing they alone understood the meaning of art and could transform it for the better did not sit well with a Victorian psyche not given to idle boasting and which gloried in men of substance – triumphs won on the battlefield, architectural structures of grandeur, engineering feats of wonder.

In 1849, the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood exhibited their work for the first time under their own banner initialling their paintings PRB and even started their own literary journal they titled The Germ, but it lasted only four months and four issues including a name change mid-way through. They had not stirred the art world as they thought they would with few granting them the same importance as they ascribed to themselves.

At least that was until John Everett Millais exhibited his Christ in the House of His Parents the following year.

This was not how the Saviour of Mankind was expected to be portrayed depicting as it did the boy Jesus amid the filth and debris of Joseph’s workshop and was considered by many to be not only disrespectful but downright blasphemous.

To a generation of Victorians who saw art as the ameliorative to the harsh realities of the society they sponsored and believed in it was an act of subversion. Even a critic such as Charles Dickens, not adverse to portraying the brutality of life in his own work was appalled writing that the family were little more than slum dwellers and that Mary doting on her red-haired boy looked like an alcoholic from the lowest gin-shop in England.

But controversy was good, at least in the short term, and for a time the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood were the talk of the chattering classes. The debate however sold few paintings and once the furore died down it seemed they were destined to be ignored.

They were saved from obscurity and neglect by the intervention of John Ruskin, the pre-eminent art critic of his day.

No mean artist himself he had remained silent for two years watching the movement develop from afar but now he wrote a long letter to The Times newspaper in praise of the Pre-Raphaelites and when Ruskin spoke Victorian Britain listened and attitudes changed.

Ruskin was to work closely with Millais travelling to Glenfinlas in Scotland where he was to have his portrait painted in suitably rugged surroundings. The reward for his patronage of Millais was not merely a portrait but separation from his wife Euphemia who was later to marry the artist after divorcing her husband on the grounds of non-consummation after seven years of wedlock.

Millais’ affair with Ruskin’s wife did little for their relationship but the great critic still remained interested in the pre-Raphaelites and so turned his attention instead to Rossetti and Holman Hunt taking his money with him.

By the end of 1853 however, the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood had virtually ceased to be unravelling on the altar of its own obsessions – women and money. The life of the starving artist appeals only to those not subject to its ravages and commercial interests soon began to outweigh high-minded ideals, for as Millais had stated early in his career: “Patrons had better buy my paintings now when I’m painting for fame, for later on I will be painting for money.”

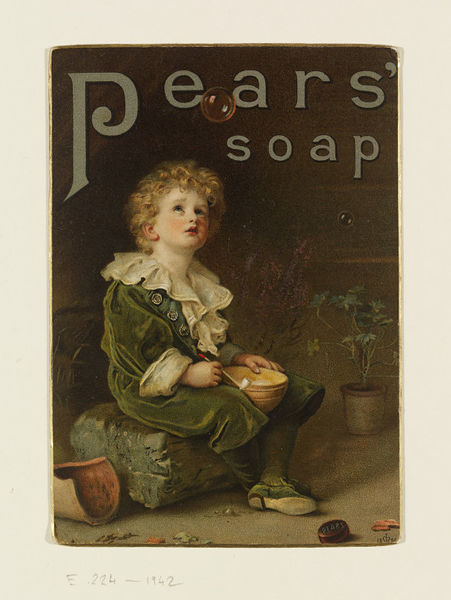

Indeed, he was to take the commercialisation of art to new heights when he sold his painting ‘Bubbles’ to the manufacturer of Pears’ Soap for use in its advertising campaign believing, rightly as it happened, that it would bring his art to a mass-audience setting a trend that has continued to this day with any number of paintings, classical compositions, and works of literature better known now for what they sell than as works of art in their own right.

Attracted to working class women not constrained by middle class Victorian conformity they often used the same models in particular Annie Miller, Fanny Cornforth, and Lizzie Siddal, so much so in fact that they became known as the Pre-Raphaelite Sisterhood.

These were real women, as they perceived them, not mere objects of beauty but mystical beings who posed in scenes from the Bible, ancient mythology and medieval fantasy would with a distant stare express that femininity which is and always will be a mystery to men.

John Everett Millais was to become one of the most popular artists of the Victorian era, and one of its richest. A particular favourite of Queen Victoria he received a knighthood and in 1895 was elected President of the Royal Academy, the very organisation he had once been so critical of. His tenure was to be brief however, for he died later the same year, aged 67.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti never truly recovered from the death of his long-time obsession and later wife Lizzie Siddal, from an overdose of laudanum in 1862. A painful separation made worse by his own aberrant behaviour when having buried his unpublished poetry alongside her declaring it would be for her eyes only, he later had the body dug up to retrieve it. He could not bear to be present but never forgave himself, nonetheless.

The worm-eaten manuscript was later published to scathing reviews that he could only have seen as poetic justice, a time when even his silence could not be judged as dignified.

Despite continuing to work and having affairs with Fanny Cornforth and another one of his models Jane Webster, there was no longer love in Rossetti’s life and he descended into a haze of alcohol and drug abuse dying in 1882, aged 53.

William Holman Hunt, always a man of deep if uncertain faith he became increasingly more so as the years passed travelling often to the Holy Land; but as befits an artist his life would not be free of scandal marrying as he did his deceased wife’s sister at a time when it was not only thought improper to do so but was in some circumstances even illegal.

Still, he lived comfortably and died a venerated artist in 1910, aged 83.

Although the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was to be short-lived its impact was significant and its influence far-ranging with many artists not only adopting both their style and technique but also happy and willing to refer to themselves as Pre-Raphaelites – it was after all revolutionary.

James Collinson, a Catholic convert who had contributed the Germ’s founding poem resigned from the Brotherhood in high dudgeon over what he saw as Millais’s highly disrespectful and blasphemous depiction of Christ.

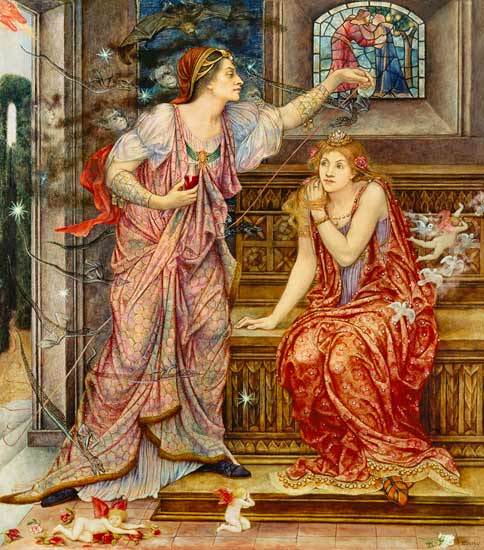

The original Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood had effectively disbanded by 1853 but its influence continued to grow and among several noted artists who came to be associated with its school of thought and artistic endeavour were William Morris, John William Waterhouse, Edward Burne-Jones Ford Madox Brown and Evelyn de Morgan among others.

Its influence can still be seen in the arts and crafts movement of the late nineteenth century and the abiding Victorian interest in Arthurian legend and its many depictions of ancient Albion.

John William Waterhouse (Lady of Shallot)

Evelyn de Morgan (Queen Eleanor)

Sir Edward Coley Burne-Jones (The Last Sleep of Arthur in Avalon)

Ford Madox Brown (The Pretty Baa Lambs)

John Everett Millais (Mariana)

Gabriel Dante Rossetti (The Roman Widow)

James Collinson (The Sisters)

Share this post: