The Regicides

Posted on 15th March 2021

English political life was thrown into turmoil following the resignation of Richard Cromwell who had succeeded his father Oliver as Lord Protector following the latter’s death in September 1658. But the well-intentioned if inept ‘Tumbledown Dick’ as he was derisively known had proven unequal to the task and after just 264 days he was permitted to resign and go into exile. He had been replaced by a Council of State but with no politician of the stature of the late Oliver Cromwell the country came under the influence of General George Monck who had previously been a Royalist before changing sides during the Civil War and becoming one of Cromwell’s most trusted lieutenants.

Monck had no desire to take power for himself or run the risk of another civil war rather he sought a smooth transition of power but his intentions for now he kept close to his chest. In early 1660 he wrote to the exiled Charles Stuart outlining the conditions that would have to be met were the Restoration of the Monarchy to be considered. Charles was quick to respond issuing his Declaration of Breda on 4 April 1660.

In the Declaration of Breda Charles vowed not to punish those who had opposed his father promising to issue a General Pardon that would protect the liberty and property rights of those who had previously supported the Commonwealth. There was opposition to any Restoration from hard-line Puritans but to the majority tired of conflict and religious stricture it was a popular move.

On 1 May, Parliament passed an act restoring the Monarchy under its new King Charles II. His reign was backdated to the day of his father’s execution, 30 January, 1649. Three weeks later on 29 May, his birthday, Charles II entered London to much public rejoicing.

As far as his promise not to seek revenge upon the so-called Commonwealth Men the new King was to be as good as his word and in August, he issued the Act of Indemnity and Oblivion or a General Pardon for those who had fought for, supported, or worked for the Commonwealth. It was in many respects a generous act of clemency and reconciliation but there were to be exceptions. On 6 June, 1660, a proclamation was issued from Whitehall:

“Charles, by the Grace of God, King of England, Scotland, France, and Ireland, Defender of the Faith. To all Our loving subjects of England, Scotland, and Ireland, greeting. We taking notice by the information of Lords and Commons now assembled in Parliament of the most horrid and execrable treason and murder committed upon the person, against the life, crown, and dignity of Our late royal father, Charles I, of blessed memory.”

The proclamation went on to name 44 men and demand they hand themselves into the authorities forthwith. It was the first indication that those men who had actively participated in the execution of his father or had signed his death warrant, known as the Regicides, were to be exempted from the Act of Oblivion and Indemnity and were liable to arrest and prosecution for high treason.

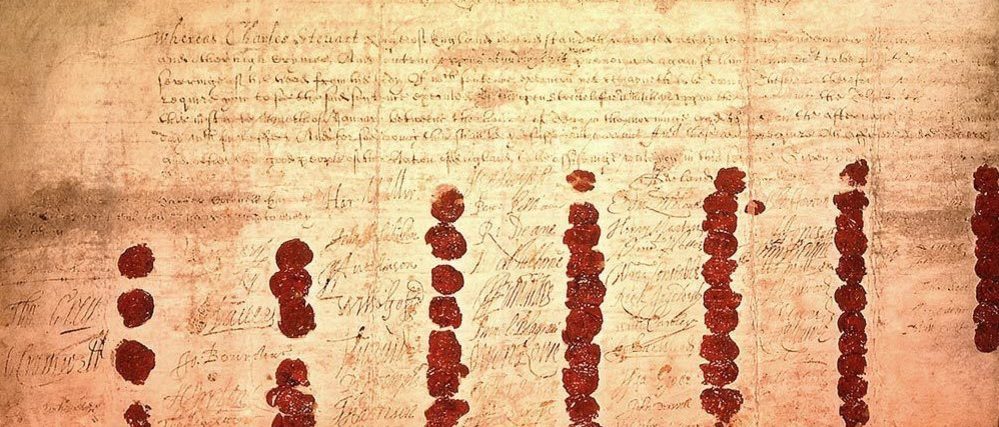

King Charles I, had been executed following a trial in which he had been found guilty of waging war upon his own people. It was not uncommon for an English King to be killed but it was unprecedented for a ruling Monarch to be tried for treason and sentenced to death according to the law. Before the sentence could be carried out however the prime mover in the trial, Oliver Cromwell, required the 70 or so Commissioners who had sat in judgement of the King to sign his death warrant. Some did so enthusiastically but others demurred or simply refused, and Cromwell had to resort to bullying and intimidation to get the number of signees he required to lend it legitimacy. In the end 59 of the Commissioners did so.

By the time the arrest warrants were issued 20 of the Regicides had already died and another 15 aware that the Restoration was imminent had fled abroad. Of these two were later to be assassinated and three abducted and returned to England to face trial and execution.

Charles was determined that none of the Regicides or those closely associated with them should escape Royal justice and troops were despatched to round them up. Some voluntarily handed themselves in hoping for more lenient treatment by doing so.

The Trial of the Regicides began on 11 October 1660 in Westminster Hall, London. The presiding Judge was Sir Orlando Bridgeman. He had previously been a Member of Parliament and during the early days of the dispute with the King he had been vocal in support of the Royalist cause. For his loyalty he had been knighted and during the war had served as the Keeper of the Rolls for Cheshire.

Following the King’s defeat, he had avoided punishment and during the Protectorate of Oliver Cromwell, had lived quietly, keeping a low profile and prospering financially. He was eager to ingratiate himself with the new regime and resume his career as one of England’s leading jurists. The opportunity to preside at the trial of the Regicides was like manna from heaven.

The Chief Prosecutor was to be Sir Heneage Finch. He was a promising and ambitious lawyer from a well-established family who had neither participated in the politics of the Civil War nor indeed in the conflict itself. Instead, he had concentrated on building a lucrative law practice in London. He had recently been appointed Solicitor-General and had lobbied for the opportunity to prosecute the Regicides.

Of those who had been arraigned five particularly vexed the authorities and were to be singled out for exemplary punishment. They were Thomas Harrison, Hugh Peters, Henry Marten, Daniel Axtell, and John Cook.

The 54-year-old Thomas Harrison was a commoner, the son of a Staffordshire butcher who had risen to be Mayor of Newcastle under Lyme. He had been sent to London to study law and soon showed himself to be no friend of the King. He sided with Parliament during the Civil War fighting in the early battles before joining Oliver Cromwell’s New Model Army in 1645. He was to become a close confidante of the Lord Protector and rise to the rank of Major-General. It was Harrison who escorted the King from his confinement on the Isle of Wight to London. Such was his reputation that the King questioned him as to whether it was his intention to murder him. Harrison who despised the Stuart Monarch told him plainly that were he to lose his life it would be the will of the people and of God that he should do so.

Harrison was a Puritan zealot and a fervent Fifth Monarchist or those who believed that the King’s death had been prophesised in the Bible and that it would usher in the thousand-year reign of the Saints. It was Harrison who first accused Charles I as being “that man of blood.” He was the seventeenth signatory of the King’s death warrant and had needed no persuading to do so.

Though he was safely under lock and key Thomas Harrison remained a dangerous man. He had been prominent throughout the Protectorate, and he knew its secrets. Many of those who had been pardoned following the Act of Indemnity and Oblivion and now sat in judgement of him were every bit as guilty as he was. He knew who they were, and he knew of their deeds. He had to be dealt with swiftly.

Sir Heneage Finch was eager to portray Thomas Harrison as a man who had acted out of malice in the affair of the King’s execution and not from any political or religious conviction. Harrison remained unrepentant, defended himself vigorously and would not be cowed. He also declared that he could see among those in Court many of his previously close associates. Parliament, he said, was at the time of the King’s execution the supreme power in the land and its authority could not now be questioned. He insisted that he had acted under the authority of that Parliament and according to the Will of God as had been so clearly expressed in the defeat of the King’s cause in the Civil War. The King had abused his powers and had been lawfully judged.

His views so outraged Justice Bridgeman who considered them little better than a second indictment of the King that he ordered the Jury not to adjourn to consider their verdict but to announce it with immediate effect. It was guilty, and the sentence that he be taken hence to die a traitor’s death - to be hung, drawn, and quartered.

Within 36 hours of the judgement being passed upon him upon, Thomas Harrison was taken for execution. Upon the scaffold he apologised for his trembling and weak condition. It was not out of fear, he said, but from the many years of bloodshed and the treatment of his guards that he stood before them less than a man.

The diarist Samuel Pepys, who witnessed the execution wrote, “To Charing Cross today to see Thomas Harrison hung, drawn and quartered. He looking as cheerful as any man could in that condition. He said he was shortly to be at the right hand of Christ to judge them who had judged him. Thus it was by chance to see the King beheaded at Whitehall and see the first blood-shed in revenge for the blood of the King at Charing Cross. Within all afternoon setting up shelves in my study.”

Hugh Peters was a firebrand Puritan preacher whose unorthodox religious views had seen him forced to take his Ministry abroad and he had been in America when he learned of the impending Civil War in England. He encouraged those young men among his flock to return to England as he would do, to take up arms against the King and for the one true religion.

Peters arrived back in England just prior to the outbreak of hostilities and was quick to immerse himself in the Puritan cause. During the Civil War he travelled with the Parliamentary Army and his well-attended blood curdling pre-battle sermons in which he preached no mercy for a Godless enemy and a King steeped in sin became famous and were regularly published. He was in effect the Puritan’s chief propagandist.

Though he was not a signatory of the King’s death warrant and had played no official role in his trial he had preached against the King in the most unflattering terms. As far as he was concerned there could be only one King on earth and that was King God, and anyone else who claimed to so be a usurper. Following Pride’s Purge and just prior to the King being put on trial for his life, and quoting from the Book of Numbers XXXV.33, he had preached in a public sermon: “Blood it defileth the land, and the land cannot be cleansed of the blood that is shed therein, but by the blood of he who shed it.”

Despite the fact he could often be vulgar and coarse in speech with his mouth often outrunning his brain it was said, he was also known for his many acts of kindness to both friend and enemy alike, but now his accusers remembered only his words. He had not been expecting to be arrested following the Restoration. He was after all neither a politician nor a soldier but merely a preacher. It was a shock from which he never recovered.

At his trial Hugh Peters was a broken man, his previous magnificent and soaring oratory had gone, and his voice was now barely audible and it was said he had tears welling in his eyes. Though he showed contrition under cross-examination for him there could be no mercy. He was sentenced to be hung, drawn and quartered. He greatly feared death and was left inconsolable at his impending fate, though he was to show greater fortitude on the scaffold than he had in the hours immediately prior to his execution.

Henry Marten was a Puritan in name only, indeed many people who knew him believed him to be an atheist. He was however an extreme Republican who was outspoken in his views. Such was his behaviour that he was as heartily disliked by many on his own side as he was by the enemy. He had been a prominent Member of Parliament throughout the years of dispute with the King but had declined to take any active part in the ensuing conflict, it being said that he would “rather command a company of whores than a company of horse.” Instead, he carped from the benches of the House of Commons demanding the trial of the King and the abolition of the Monarchy. If his religion was uncertain and his morals loose, then his Republican ideals remained steadfast.

Though Cromwell loathed Marten whom he considered a greedy, corrupt and drunken libertine (ironically a dislike he had shared with the King who had described him as an “ugly rascal and a whore-master,” they worked closely together as members of the Council of State in laying the ground rules for the trial of the King and later the creation of the Commonwealth.

At his trial Marten made no excuses for his actions and presented no defence as such, after all everyone knew he was an unequivocal republican, and everyone knew of his participation in the events now described, as such his guilt was beyond doubt. He was however no religious zealot, he was not the stuff of which martyrs were made, and though he may have been willing to speak in defence of the cause in which he believed he was not willing to die for it. Having expressed regret at the King’s death he threw himself upon the mercy of the Court and begged for clemency.

Henry Marten had been the leading surviving architect of the King’s trial and execution, even coming up with the words for the indictment, yet despite being found guilty of high treason he still had many powerful friends and by hook or by crook, he was somehow spared the death penalty and instead sentenced to life imprisonment.

After a number of years spent in the Tower of London the prisoner Henry Marten was moved to Chepstow Castle at the request of Charles II who objected to such a notorious Regicide being confined in such close proximity to himself.

His life in prison was not particularly arduous and an entire wing of the Castle was set aside for his use, and he was permitted to walk within its grounds. He was attended upon not by his wife but by his mistress but there was never any prospect of his being released. He was to die on 9 September 1680, aged 78, when he choked on his supper, a drunk of whom it was said his mind had long since gone.

Daniel Axtell was a professional soldier who had been appointed to command the troops guarding the Courtroom where the King was tried, the so-called “Black Guard.” He had been a grocer in Berkhamsted prior to the Civil War and a practising Baptist. He had enlisted in Cromwell’s New Model Army and very quickly took to army life becoming a fervent supporter of the Good Old Cause. He fought during the Civil War and for Cromwell in Ireland where he participated in the massacres at Drogheda and Wexford earning a reputation for brutality. He was a man who could be relied upon to do as he was told without question.

The trial of King Charles I had been no orderly affair. Cromwell had wanted the determination of the King’s guilt to be a public event and people crammed into the Painted Chamber of the Palace of Westminster to witness it. The atmosphere then was raucous with the King’s appearance being greeted with both howls of derision and cries of God Save the King.

The soldiers under Axtell’s command that ringed the Courtroom were not there to protect the King but to prevent any attempt to free him and to intimidate those present. Axtell revelled in his task encouraging his men to drown out the words of the King with cries of justice and treason. When the Lady Fairfax, wife of the Commander of the Parliamentary Army who had hidden her face behind a veil cried out “Oliver Cromwell is the traitor,” Axtell ordered his troops to aim their muskets and it appeared for a moment that they were about to fire.

At his trial Daniel Axtell’s defence was that he was merely obeying orders. Sir Heneage Finch was quick to exploit this, had he then been ordered to silence the King, to bully the jury, to intimidate the crowd, were his orders not then illegal? As in future trials of similar import the defence “I was only obeying orders” was to prove to be no defence at all. He was sentenced to death.

John Cook was the son of a farmer who had been born in Leicester in 1608 but he never had any intention of following in his father’s footsteps. From an early age he read avidly and what he read was law books. For him the law was more than a mechanism to maintain social order but a means to guarantee the public good, for him it was never just a profession but a love affair. He enjoyed nothing more than to debate the law believing that it should exist to the benefit of all. Many of the ideas he propounded such as the right to silence, bail for the accused and financial aid for those who could not afford legal counsel have since become integral to our legal system.

He had made his name defending radical politicians such as the leader of the Levellers, John Lilburne. He was not however political himself and he had not been heard to express explicitly anti-Monarchical views, but he saw in prosecuting the King the opportunity to show that no one was above the law.

Nonetheless he had not been first choice to prosecute the King being seen as somewhat of a loose cannon and had only been appointed to the role after a number of more prominent jurists had cried off or feigned illness to avoid having to take such a poisoned chalice.

Despite the gravity of his situation John Cook was looking forward to the opportunity to lock horns in open Court with Sir Heneage Finch whom he knew. He spoke eloquently of not being politically motivated and of never having acted out of malice. He had conducted himself in the prosecution of the King according to his client’s wishes and to ensure that the law was seen to be done and that justice seen to prevail. He defended himself well and there were times when he made Sir Heneage Finch appear uncertain and hectoring.

Unfortunately, John Cook’s defence had already been effectively undermined by the presiding Judge Sir Orlando Bridgeman who in his pre-trial statement had declared that the King was above the law and not subject to it thereby his trial was illegal. He would not countenance any argument that declared at the time of the trial Parliament was the supreme power in the land.

When Cook, who never tired of discussing anything relating to the law responded by also stating that the trial of the King was not strictly legal because of his refusal to enter a plea (it was usual for the accused who refused to plea to be taken away and have large boulders placed on his chest until he either pleaded guilty or not guilty or was crushed to death. But no one dared suggest doing this to the King) it was as good as an admission of guilt.

John Cook was found guilty and sentenced to a traitor’s death. He accepted his fate with equanimity and thanked the Prosecution Counsel, the Judge, and the Jury declaring that he’d had a fair trial.

On the night before his execution John Cook wrote a last letter to his wife:

“We were not traitors, nor murderers, nor fanatics but true Christians and good Commonwealth men fixed constant in sanctity and truth, justice and mercy which the Parliament and Army dared engage for. We sought the public good and would have enfranchised the people and secured the welfare of the whole groaning creation if the nation had not more delighted in servitude than in freedom.”

On the morning of 16 October John Cook was strapped to the hurdle that would carry him to his place of execution. Placed on the hurdle with him within his eyesight was the head of the previously decapitated John Harrison. Those who would follow him to the scaffold would be shown his mangled and partially dismembered corpse as a reminder of what awaited them.

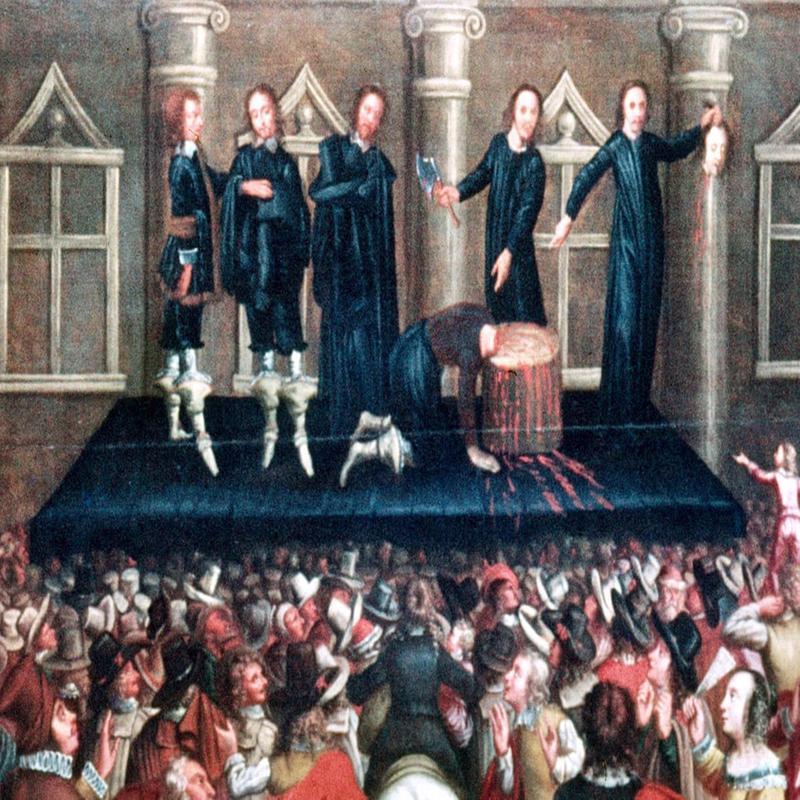

The Trial of the Regicides had lasted less than a week, of those who came before the Court ten were committed to the scaffold of whom six were signatories of the King’s death warrant - Thomas Harrison, Adrian Scrope, John Jones, John Carew, Thomas Scott and Gregory Clement. Two were guards Daniel Axtell and Francis Hacker; the preacher Hugh Peters and the prosecution counsel John Cook. Nineteen others were sentenced to life imprisonment. Those still in exile were to remain in fear of abduction and assassination for the rest of their lives.

The Judge and Prosecution Counsel at the Trial of the Regicides received the thanks and eternal gratitude of King Charles II who rewarded them accordingly. Sir Orlando Bridgeman was to be promoted to Chief Justice of the Court of Common Pleas and later Lord Keeper of the Great Seal. Sir Heneage Finch was to be appointed Solicitor-General and Lord Chancellor. In 1682, just prior to his death he was promoted to the peerage becoming Lord Nottingham.

In January 1661, the corpses of the Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell, the Commander f the New Model Army Henry Ireton, and the Judge at the trial of King Charles I, John Bradshaw, were disinterred and in their death shrouds hung from gallows in Tyburn, their skulls removed and impaled at Westminster Hall.

The Merry Monarch had had his revenge.

Tagged as: Tudor & Stuart

Share this post: