The Scottsboro Boys

Posted on 23rd March 2021

On the morning of 25 March 1931, a train was running along the Southern Railway between Chattanooga and Memphis. Riding on the roof of the train was several hobos both black and white. As it passed through Lookout Mountain a white boy stood on the hand of 18-year-old Haywood Patterson almost knocking him from the train. According to Patterson the boy said to him, “This is a white man’s train, all you nigger bastards unload. But we weren’t going anywhere so there was a fight. We got the best of it and threw them off.”

Riding the rails, though it was illegal, was the easiest way for poor Southerners to travel from town to town to look for work. It was also one of the few places where white and black people in the strictly segregated Deep South would come into regular contact with one another on relatively equal terms. It was a tough life and violence was not uncommon though it was rare for the different races to come to blows. Even so, it seemed like just another fight, but it wasn’t to be.

The train was due to stop at the small town of Paint Rock, Alabama. Long before it arrived however news of the fight had already reached the town and a gang of white men armed with guns and clubs had gathered ready to teach these black boys a lesson. Fortunately for the young men concerned the police were also on the scene and as soon as the train stopped they were arrested and spirited away before the lynching that some certainly intended could occur.

As the boys were being taken away two young white women emerged from the train. They were 21-year-old Victoria Price and her friend 17-year-old Ruby Bates. With their hair tied back and dressed in dirty overalls both were mistaken at first for boys.

They appeared to be unlikely friends. Ruby Bates was very feminine, softly spoken and almost shy in manner. Victoria Price was the opposite she had already been twice married, was as tough as old boots and wasn’t afraid to speak her mind. Both women had worked in the Textile Mills of Huntsville, Alabama, but the economic depression had forced wages so low that they had been forced to move to the poor black neighbourhood of town and had been reduced to selling sex to both white and black men to support themselves.

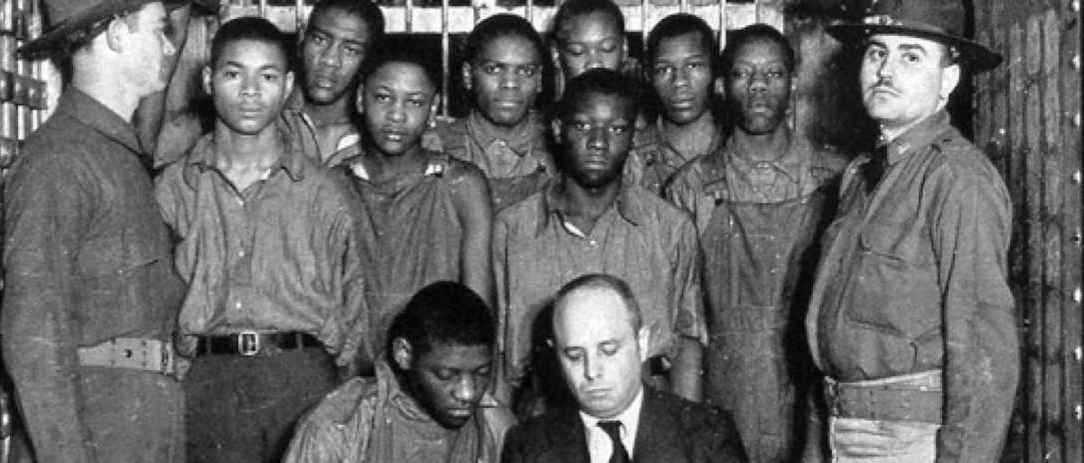

As the boys, Clarence Norris (19) Andy Wright (19) Haywood Patterson (18) Olen Montgomery (17) Willie Roberson (16) Ozie Powell (16) Charlie Weems (16) Eugene Williams (13) and Roy Wright (13) were taken to the jail in nearby Scottsboro news began to circulate that Victoria Price and Ruby Bates had accused them of rape and the news travelled fast.

Within days people from all over the Deep South were picketing the jail at Scottsboro and their mood was ugly. They demanded that the boys be handed over for summary justice. The Sheriff Matt Wann refused to be intimidated and said he would shoot dead the first man who attempted to move on the jailhouse, but he feared they might storm it regardless. He hastily contacted Alabama’s Governor Benjamin M Miller demanding he call out the National Guard for the boy’s protection.

In the Deep South of the 1930’s it was a widely held view that black men had an insatiable desire to defile and rape white women. The preservation of white womanhood and keeping them out of the hands of sexually depraved blacks was a matter of Southern honour. As a result, rape in Alabama as it was in many other States in the Deep South was a capital offence. Indeed, of the near 5,000 black men lynched between 1880 and 1940 most had been accused of sexual offences against white women.

The Scottsboro Boys, as they were to become known, went on trial on 6 April 1931. Hundreds of National Guardsmen ringed the Courthouse to protect it from the angry mob that had gathered outside. It had proved almost impossible to provide them with a Defence Counsel and when one was found he was almost 70 years old, had not defended a case for years and was wholly inadequate to the task. In the end a Real Estate Attorney, Stephen Roddy, who had almost no knowledge of the Alabama Criminal Code was persuaded to help out and was paid $60 a day for doing so. He did his best in impossible circumstances.

The atmosphere in the Courtroom, though the proceedings were conducted with the usual decorum was tense and strained and the attitude towards the defendants little less hostile than that being expressed by the crowd outside that ringed the Courthouse. A prevailing presumption of guilt was evident.

On the witness stand Victoria Price described in detail what had taken place, “There were six for me and three for her, two were holding my legs and another had a knife to my throat, while another ravished me. That one (pointing at Clarence Norris sitting behind the Defendants Counsel) took my overalls off. Six of them had intercourse with me. Pork her! Pork her! They hollered.” When Ruby Bates turn came to testify, she concurred with Victoria Price in every detail.

When it came to the nine defendants to testify most denied that they had even met the two young women on the train, and they all denied having sexually assaulted them. Instead, in their testimony, which often seemed muddled and confused, they appeared to accuse each other. The all-white jury did not deliberate long before finding them all guilty of assault, kidnapping, and rape. Just four days after the trial had begun on 9 April 1931, Judge A E Hawkins returned a sentence of death by electric chair for all the convicted men except for 13-year-old Roy Wright.

Many people in the North believed the Scottsboro Case just another incident of the Southern judicial system behaving little better than a legalised lynch mob; and whereas Southern whites might presume black guilt Northerners were no less inclined to see only injustice and presumed their innocence.

Though the case had made headlines there was no reason to think that it hadn’t been dealt with properly and would go no further; but an unlikely and unexpected champion for the Scottsboro Boys now emerged in the form of the American Communist Party. The case had been brought to their attention following a demonstration in Harlem, New York. The Communists had gained a foothold in the industrialised North and had been prominent in many of the labour disputes, often fought over the issue of trade union recognition that had plagued industrial relations in the preceding few years. They had failed however to make a similar impression in the more rural South particularly among the black sharecroppers and agricultural labourers. As a result, any inflamed sense of injustice with regards to the Scottsboro Boys was secondary to their value as a propaganda tool.

Communist Party representatives persuaded the relatives of the defendants to permit their legal arm International Labour Defence to organise their appeal against the sentences. The swift actions of the Communists had effectively sidelined the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP) which had also expressed an interest in taking the case.

The lawyers for the International Labour Defence petitioned Judge Hawkins for a retrial on the grounds that the defendants had not been provided with an adequate Defence Counsel and had been denied access to an Attorney. Judge Hawkins denied the motion. The I.L.D now took the case to the Alabama Supreme Court also citing that blacks had been excluded from the jury making it racially biased in favour of the prosecution case. The Supreme Court also found against them, but the appeal had at least brought a stay of execution.

On 10 October 1932, the case at last reached the Supreme Court of the United States who found by a vote of 7 to 2 that the Defence Counsel had indeed been inadequate and along with other procedural errors had been a violation of the defendant’s civil rights as enshrined in the Fourth and Fifteenth Amendments.

The case was returned to Judge Hawkins with the recommendation that he order a retrial. He was an elderly Southern gentleman of the old-school who never doubted for one moment that he had presided over a fair trial and was deeply offended at any suggestion that he had not. He was appalled by the Supreme Court’s decision but had little choice but to concur. The re-trial was ordered, and he also agreed to the Defence Counsel’s request for a change of venue but not to more cosmopolitan Birmingham as they suggested but instead to the small town of Decatur in the heart of rural Alabama.

The I.L.D wanted the case to be as high-profile as possible and so decided to hire the services of Samuel Leibowitz, the most famous Criminal Defence Attorney in America after Clarence Darrow. Though a confirmed Democrat he was by no means a communist openly expressing the view that he was repelled by their ideology. He was eager to take the case however which he saw not just as a matter of criminal law but as a civil rights issue and an opportunity to force the backward South into line with the rest of America.

Even though he was much admired and was believed never previously to have lost a case he was in many respects a strange and ultimately disastrous choice. He had nothing in common with the people of Alabama. He did not share their values; he did not share their politics and he certainly didn’t share their religion. He was ignorant of life in the South and was impervious to Southern sensibilities. He was as culturally alien to them as the people he was going to defend, and nothing was more guaranteed to stiffen the resolve of Alabama not to yield than this prosperous liberal Jew from the North telling them what to do and how to behave.

The Jackson County Sentinel was to write during the Second Trial: “Seventy years ago the scallywags and carpetbaggers marched into the South and declared that the Negroes are your equal and you will accept them as such. Now the Reds of New York, march into the South with their law books and again declare that the Negroes are your equal and you will accept them as such. We will not!”

Whilst the various appeals and legal arguments continued to be heard the Scottsboro Boys remained on Death Row in Kilby Jail. There they had a miserable time always in fear of a beating from the guards for the slightest infraction of the rules and having to listen to the screams and last-minute prayers of those on their way to the electric chair.

The Second Trial of the Scottsboro Boys was due to be held on 27 March 1933, Judge James Edwin Horton presiding. In the months preceding it Ruby Bates had disappeared and no one knew where she could be found. It was feared that she may have been kidnapped to prevent her from testifying, or even murdered.

Samuel Leibowitz had won a motion to try the defendants separately, but it was the prosecution who decided who should take the stand first. They chose Haywood Patterson because he was the one who in their eyes most fitted the notion of the bad black man in the febrile Southern imagination. He was particularly dark skinned, had a scowl on his face, a mean look in his eye and a foul mouth. But Leibowitz remained confident believing that if he could acquit Patterson then surely, he would acquit the others also.

For the sake of clarity Leibowitz had produced a model of the train on which the crime had been committed with which to prove the inconsistencies in Victoria Price’s earlier testimony. When however, he asked her if the model train was similar to the one she had ridden on she replied to roars of laughter that, “The one I rode on was a lot bigger”. It was an early example of what was to come and a reminder to Leibowitz if he needed one that this wasn’t going to be easy. Regardless of this early setback he persisted with his line of questioning and making constant reference to the train he proceeded to press Victoria Price as to where exactly these offences were supposed to have taken place. She was often evasive in her answers frequently saying that she could not remember but she did so in such an aggressive fashion and was so entirely dismissive of the train as being nothing but a toy that despite proving the inaccuracies in her statement Leibowitz’s use of it diminished rather than enhanced his case. Referring back to the earlier testimony from Dr Bridges at the First Trial that during his physical examination of the girls he had found no sign that violence had been committed, that there was no vaginal tearing and that he had only found traces of dead semen, she merely shrugged her shoulders.

Victoria Price had earlier testified that she and Ruby Bates had spent the night before they boarded the train in a Guest House in Chattanooga run by a woman named, Callie Broachie. Leibowitz had spent the previous few days pacing the streets of Chattanooga hunting high and low for this Guest House and this Callie Broachie but could find no trace of either. There was in fact a Callie Broachie but she was a fictional character who regularly appeared in stories in the Saturday Evening Post. When this was put to Victoria Price, she claimed never to have heard of it.

Leibowitz claimed that he knew exactly where she and Ruby Bates had spent that night and he could prove it. He now produced a witness, Lester Carter. He was a drifter who regularly rode the trains and now he testified that he had spent the night before the supposed rape took place at a gathering point beside the railway tracks known as the Hobo Jungle where Victoria Price introduced him to Ruby Bates. After talking and walking the tracks for a time they returned to the Hobo Jungle where he had sex with Ruby Bates whilst Victoria Price did likewise with her boyfriend, and that it was this that had produced the traces of dead sperm that were later found in their bodies.

Victoria Price denied all of this, she had never even met Lester Carter, and she and Ruby Bates had spent the night at Miss Callie Broachie’s Guest House. It wasn’t her fault if the Prosecution Counsel couldn’t find it. When Leibowitz then asked her how she and Ruby had spent the night in the Guest House – what did they do? How did they pass the time? Price said she couldn’t recall.

Leibowitz had cross-examined many evasive, aggressive, and even supremely clever witnesses in the past but Victoria Price’s unflinching denials, refusal to be cowed even by the most damning evidence against her, and her constant rebuttal of his questions with “I don’t remember,” or “I can’t recall,” seemed to leave him flustered.

Regardless of the inconsistencies of her previous testimony put to her, regardless of the vagueness of her statements, regardless of the witnesses he produced, Victoria Price remained adamant that the black boys had raped her. When Leibowitz turned to her and said, “You’re a pretty good little actress aren’t you,” she simply replied, “Well, you’re not a bad actor yourself.”

It seemed to Leibowitz that he was tearing Victoria Price’s testimony apart and unmasking her for the deceitful whore he undoubtedly thought she was. When he put it to her that she was “a foul, contemptible, outrageous liar,” she replied in a firm voice “No, I am not.” Leibowitz did not understand the Southern mindset however, and his unashamedly brutal attacks on Victoria Price’s character they perceived to be an assault on the dignity of Southern womanhood itself.

Leibowitz proceeded to undermine and tear apart the testimony of most of the Prosecution’s witnesses. One man who had claimed to have seen the girls with the defendants on the train was forced to admit he had not. Another who had said he had witnessed the earlier fight between the white and black boys was made to concede that he had not been on the train at all whilst another had described the girls as wearing women’s clothes when they had in fact been dressed in overalls. He still had one final trick up his sleeve, however.

Ruby Bates, who had disappeared months earlier, had in fact fled to New York where she had been tracked down by members of the I.L.D. They had kept her in isolation and away from the prying eyes of the press, now she re-emerged in the Decatur Courthouse as a witness for the Defence. When she was called to take the stand audible gasps of astonishment were heard to come from those present, and her physical appearance did likewise. She was no longer the poor white girl dressed in dirty overalls who had to ride the trains because she couldn’t afford the fare and was forced into prostitution to make ends meet. She looked immaculate and was perfectly made up, her nails had been manicured, her hair cut in the latest style, and she was wearing a fashionable dress with silk stockings and a fancy hat. She was it seemed too many dressed like a Northern woman, so unlike the smart but plainly turned-out Victoria Price.

Her performance on the stand did not match her appearance, however. Though she was to testify that she had not been raped by the defendants and had been told what to say and do by Victoria Price who had threatened that she would go to prison for vagrancy if she did not, she was hesitant and uncertain. Her case was not helped by the behaviour of Victoria Price and her constant shrugging of the shoulders, shaking of the head, sideways glances towards the Jury and frequent stifled laughter indicating that she was either scared, stupid, or simply lying.

Ruby Bates testimony stood in stark contrast to that of Victoria Price. Where Ruby seemed vulnerable, easy to manipulate, and intimidated by the whole affair, Victoria was brash, confident, and spoke with such certainty about events that it was difficult not to be impressed. Even when she could not satisfactorily answer a question she did so without hesitation and in such a manner that she made it appear that it was a stupid question to be asking in the first place. She seemed so convinced of the veracity of what she was saying that it was difficult for others not to be convinced also.

The Prosecution Counsel now made hay with her links to the Communist Party.

Where had she been? Who had been taking care of her? Who had provided her with her fancy clothes? Who had brought her to Court?

Every time she answered the Communist Party the Court was reduced to howls of laughter. Wasn’t it the case that she was nothing but a Communist Party stooge? The star witness for the Defence had turned out to be a disaster.

Despite the unexpected turn of events regarding Ruby Bates testimony, Samuel Leibowitz remained confident that he had done enough to prove his client’s innocence beyond any reasonable doubt. The Jury however was to think otherwise.

In his summation Wade Wright for the Prosecution pointed towards the Jury and said to them “Show them that Alabama justice cannot be bought and sold by Jew money from New York.” Leibowitz was outraged but was to be even more so by the guilty verdict that followed. Haywood Patterson was once more sentenced to die in the electric chair.

Samuel Leibowitz had been shattered by the verdict and was described by some as almost being like a broken man. It was the first time he had experienced the justice system in the Deep South and he neither understood it nor the character of the people it represented. They were not impressed by clever tricks and fancy words, and it had been a harsh lesson to learn. By the time he returned to New York, buoyed by the response of his many supporters who admired the manner in which he had fought the case, his spirit returned, and he vowed to fight on. He told them, “If you ever saw those creatures, those bigots whose mouths are slits in their faces, whose eyes popped out at you like you frogs, whose chins dripped tobacco juice be-whiskered and filthy, you would not ask how they could do it.” Even now he still didn't understand, and the words were to come back to haunt him. To those in the South this rich, arrogant Northern Jew had at last revealed his true colours.

Leibowitz once more motioned Judge Horton for a re-trial. Horton by now had his own doubts about the guilty verdict. He did not believe Victoria Price’s testimony and at the very least the defendant’s guilt had not been proved but he also knew that Southern public opinion was firmly behind the verdict. If he ordered a re-trial, it would almost certainly be detrimental to his career. On 22 June 1933, he made the toughest decision of his life - he overturned the verdict and ordered a re-trial.

Alabama Attorney-General Thomas Knight still heading the Prosecution Counsel now moved to have Judge Horton removed from the case. He was successful and he was replaced by 70-year-old Judge William Callahan.

In the meantime, the Scottsboro defendants were returned to the torment of Death Row to await the outcome of the appeal never knowing if the next time they were led from their cells it would be the last. The stress of their continued incarceration was evident and they began to fall out among themselves. Clarence Norris stabbed Haywood Patterson in a brawl over a gambling debt while Ozie Powell slashed the throat of a Prison Guard and was shot in the head by another Officer. He survived his wounds but it was said thereafter that he was never the same.

The Third Trial began in November 1933. The presiding Judge, William Callahan was a product of the Old South brought up during the period of Reconstruction and subject to well-established prejudices not just relating to black people but also so-called Northern Carpetbaggers. He made it plain to the Jury before the trial began that no white woman not under duress would agree to have sex with a black man instructing them that; “When a woman charged to have been raped, as in this case, is a white woman, there is a very strong assumption under the law, that she will not and did not yield voluntarily to intercourse with the defendant, a Negro.” He was to repeat this statement before the summation. He also remained hostile to Samuel Leibowitz throughout, regularly objecting to questions that seemed to impugn Victoria Price’s character, dismissing most of the Defence Counsel’s own objections, and excluding many of their key witnesses.

The Third Trial of the Scottsboro Boys was little more than a farce. Once more the verdict was guilty and the sentence again that the defendants be put to death by electric chair. Leibowitz was both despondent and downcast by the whole business and no longer believed he could get the boys acquitted. He would fight on however to have the death sentences overturned. If he could not win them their freedom, he could at least save their lives.

Throughout the Second Trial he had made frequent reference to the fact that there had been no blacks in the pool of good citizens from which the Jury would be chosen. Were they unqualified to do so, or were they deliberately excluded, he asked. When he produced expert black witnesses to testify, he had protested at the disrespectful way they were treated and spoken to by the Prosecution Counsel, in particular Thomas Knight. Perhaps without realising it he had assiduously established the grounds for a further appeal though at the time it was widely held that he was political point-scoring and trying to prove that Southern society was backward, its people ignorant and racist, and that its judicial system reflected and reinforced both these things. Judge Horton had not taken kindly to his grandstanding designed to appeal to the Northern press and the wider world. Now it would serve him well.

Leibowitz once more appealed the verdict and once again the Alabama Supreme Court rejected it and he was forced to take it to the United States Supreme Court. He appealed on the grounds that the composition of the all-white Jury was a clear violation of their rights to equal protection under the law. He also produced copies of the Alabama Court Rolls going back decades that showed all white Juries, (not just in trials involving black defendants) were almost universal in Alabama and that black juror’s names had been clumsily entered in pen afterwards to make it appear that this was not the case. Black citizens, he argued, were deliberately excluded from Jury service in the State of Alabama. In a ground-breaking decision by a vote of 7 to 2 the Supreme Court in Washington agreed. Once more there would be a re-trial.

By this time Alabama was heartily sick of the whole affair, the Court Case rumbled on becoming ever more expensive and the people of the South were being seen as ignorant bigots little better than savages in the eyes of the world. The State of Alabama was the subject of widespread ridicule. They were looking for a way out. Even the editor of the Montgomery Advertiser, Grover Hall, who had been a fervent supporter of the Alabama Court and convinced of the boys’ guilt thought it was time to bring it to an end. He wrote, “Scottsboro has stigmatised Alabama throughout the civilised world. We here would suggest and urge that the State move for a decent, dignified compromise. Nothing can be gained from demanding the final pound of flesh. Throw this body of death away from Alabama.”

The Prosecution let it be known that they might consider reducing the sentence of death to one of life imprisonment and that some of the defendants might also be eligible for parole but only if Samuel Leibowitz stood down. Having to stand aside was a personal humiliation for Leibowitz but the threat of continued intransigence on the part of the Judiciary in Alabama and the likelihood of another guilty verdict if he continued to head the Defence Team forced him to do so. He was replaced by a Southern attorney.

The Fourth Trial of the Scottsboro Boys was set to begin on 20 January 1936, and once more it was to be presided over by Judge Callahan. As had by now become usual procedure the defendants were to be tried separately. Samuel Leibowitz was present on the Defence Team but in an advisory capacity only and roiled on the side-lines as yet again the Scottsboro Boys were found guilty. This time however the death sentence did not follow conviction. Between January 1936 and July 1937, Ozie Powell, Clarence Norris, Andrew Wright, Charlie Weems, and Haywood Patterson were sentenced to terms of imprisonment ranging from 20 to 105 years.

On 27 July 1937 the State of Alabama dropped all charges against Eugene Williams, Roy Wright, Willie Roberson, and Olen Montgomery. The decision drove Grover Hall to pose the question how the Scottsboro defendants could be half guilty and half innocent when they had all been convicted on the same flawed evidence?

Regardless of the doubts cast upon the consistency of the Courts judgement for the supporters of the Scottsboro Boys it was a victory of sorts and by the following day the four men had been spirited to New York where they were greeted by Samuel Leibowitz and received a hero’s welcome. Treated as celebrities and provided with new clothes they partied and re-enacted scenes from their trial at the Apollo Theatre before being taken on a short speaking tour where they answered the questions of an inquiring press. Their fame was to be short-lived however, and no sooner had they been thrust into the spotlight than they once again faded from view.

Those who had in the past been their most vocal supporters had seen their agendas satisfied. As far as the American legal system was concerned the Scottsboro Trials had been an embarrassment that was best forgotten. In any case, the Scottsboro Affair was old news, things had moved on. When unable to find regular work the four men appealed to those who had supported them during their trial their appeals went largely unanswered. They were left to fend for themselves.

For those defendants sent back to prison it was a time of darkness and utter despair. There would be no further appeals, no further trials, and it seemed that they would never be released. As time passed and the Scottsboro Affair began to fade from memory and become a mere footnote in history the State of Alabama began to relent. After three previously unsuccessful appearances before the Alabama Parole Board in April 1943, they voted to release Charlie Weems. Over the next few months, they also released Andy Wright and Clarence Norris. In early 1946, Ozie Powell became the last defendant to be paroled.

Haywood Patterson however remained in jail. His recalcitrance, and refusal to be cowed or intimidated had singled him out for special treatment and he had quickly become absorbed by the prison system. He was aggressive, often violent, frequently in trouble and hated by the Guards. On one occasion he was stabbed numerous times in an attack that left him with a punctured lung. He was also an aggressive homosexual who fought often with other prisoners to keep his gal.

In July 1948, he escaped from a work detail and fled to Detroit where he secretly had his autobiography published. In December 1950, he was arrested once more for killing a man in a bar room brawl and returned to prison. He died of cancer in prison on 24 August 1952.

Charlie Weems moved to Atlanta in 1943, married, found work as a laundryman, and lived quietly.

Andy Wright was soon back in Kilby prison for violating the conditions of his parole. He wasn’t released again until 6 June 1950. He then moved to New York where the following year he was charged with raping a 13-year-old girl white girl. He was acquitted by an all-white Northern Jury.

Ozie Powell moved back to his home State of Georgia upon his release where those who had known him previously said he had changed as a result of the gunshot wound he had received to the head. He quickly faded into obscurity.

Olen Montgomery could never settle down and moved from State to State and took to hard liquor. He was never able to hold down a job for more than a few months.

Eugene Williams moved to St Louis saying he was going to fulfil his ambition to play in a jazz band. It is not known if he ever did.

Willie Roberson moved to New York where he would often be heard to complain about his ill-fortune, particularly after being wrongly arrested once more for disorderly behaviour. Eventually, with the support of family he married, found regular work and settled down to a quiet life. He was to die of an asthma attack.

Roy Wright enlisted in the army and later the merchant navy. Returning home from a long period away at sea he convinced himself that his wife had been having an affair in his absence. In 1959, he shot her dead before turning the gun on himself. He was found still clutching his Bible.

Clarence Norris moved to New York and was briefly returned to prison as this was a violation of his parole. Upon his release he moved to Cleveland before eventually returning to New York. Finding himself out of work in 1956 he approached Samuel Leibowitz who helped get him a job as a dishwasher. Though he married and raised a family he was never able to reconcile himself to the injustice that had been inflicted upon him and the others in the 1960’s he contacted the N.A.A.C.P to help him get a pardon from the State of Alabama. In 1976, in an emotional ceremony he was granted a pardon by Governor George Wallace. It was believed at the time that he was the only one of the Scottsboro Boys still alive.

Although Samuel Leibowitz continued to prosper, he felt deeply the personal humiliation he had endured at the hands of the Alabama State legal system and never fully came to terms with the degree of hatred that had been levelled at him. During the 1940’s he was promoted to be a Judge on the New York District Court where he became a keen advocate of the death penalty. He died on 11 January 1978, aged 84.

A year after he overturned the conviction of Haywood Patterson and ordered a retrial Edwin James Horton was defeated in the election to the District Court and never served on the Bench again.

Unable to remain in or return to the South over the next few years Ruby Bates appeared on Communist Party platforms in the North and elsewhere where she apologised for her role in the conviction of the Scottsboro Boys. In 1940, she moved to Washington State where she married and lived quietly. She did not finally move back to Alabama until 1965. She died on 26 October 1976, aged 61, a week after her husband and just two days after Clarence Norris received his pardon.

Victoria Price was to disappear so completely from view that it was assumed by many people who had been involved in the case that she must be dead. In 1976, now known as Katherine Streeter since her marriage to a Tennessee farmer she re-emerged from obscurity to successfully sue the broadcaster N.B.C who in a docudrama about the Scottsboro Affair had portrayed her as a liar and a prostitute. She remained adamant that she had told the truth all along saying that “I didn’t lie in Scottsboro, I didn’t lie in Decatur, and I ain’t lied here. I’ve told the truth the whole way through.”

The case was settled out of Court. She died in 1982, aged 71.

On 19 April 2013, in a ceremony held at the Scottsboro Boys Museum the Republican Governor of Alabama Robert Bentley signed House Joint Resolution 20 granting the remaining defendants in the Scottsboro Case a posthumous pardon.

Tagged as: Modern

Share this post: