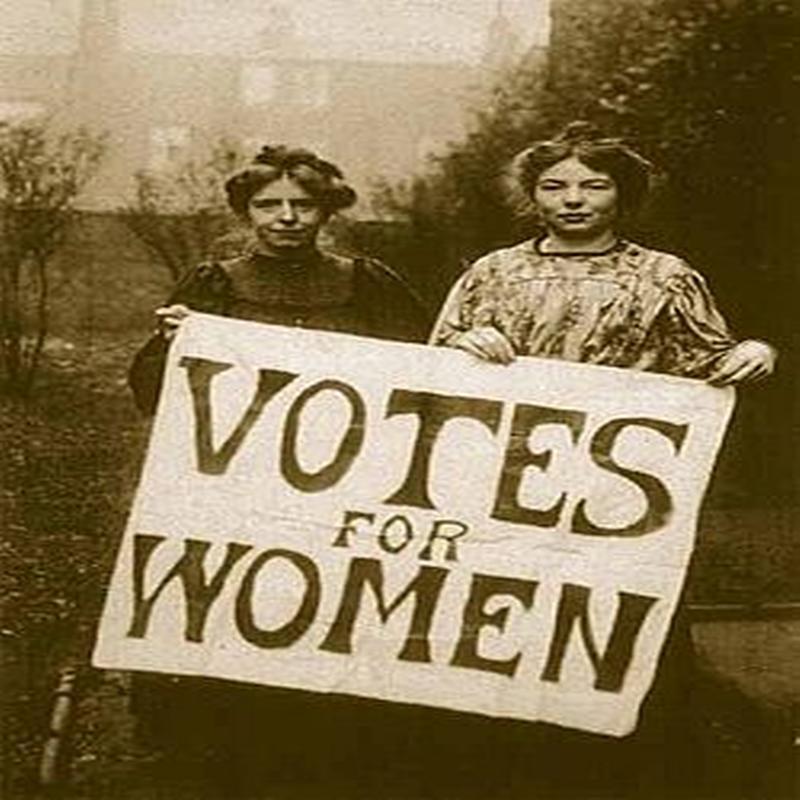

The Suffragettes: Votes for Women

Posted on 21st January 2021

Can a morally defensible cause justify in and of itself the means adopted to achieve it? It was a question that would vex the various groupings which coalesced in the fight for female equality and women’s suffrage; a campaign that was at the same time both high-minded and street politics of the most meanly conceived kind which overtime would spiral from civil disobedience and public protest to intimidation and outright violence. Indeed, it is likely today that one wing of the movement at least would have been designated a terrorist organisation.

Like much of Victorian society the parameters of acceptability were plainly drawn and the position of women within them clearly defined. They were expected to be the ‘Angel in the House’ the title of a popular poem from 1854 by Coventry Patmore that exalted both the woman’s subordinate and decorative role; they were meant to conceive children, provide a good home, and be at the beck-and-call of their husbands. Any rights they had in domestic affairs, in property, or even over their own bodies were far and few between. This of course related to middle class women, those further down the social scale did not only have to work merely to survive but were expected to do so.

Conditions for women improved as the nineteenth century progressed, they were permitted to retain the money they earned, and divorce was made easier. There were also to be greater educational opportunities with the Education Acts of 1870 and 1876 providing basic schooling for girls alongside that for boys. But the changes were slow, and women had no say in the laws that governed their lives or in how those laws were conceived and made.

Somerville College was established in 1879 specifically for women under the umbrella of Oxford University but it did not permit the graduation of its students and though other Colleges followed suit it was only in those subjects deemed fit for female study. For example, when Elizabeth Garrett qualified as Britain’s first female doctor the institution where she did her training rather than take pride in her achievement changed their rules so it could not happen again.

Even so, women did participate they could for example serve on school boards and even in certain circumstances vote in local elections, but they remained firmly excluded from national politics. Disraeli’s Electoral Reform Act of 1867 had provided the ray of hope that this might change, and it did indeed see an additional 2.5 million names appear on the Voting Register, none of whom were women. But the notion of the Angel in the House was changing.

In March 1865, a small number of mostly single, career-oriented women among them Dorothea Beale, Helen Taylor, Anne Clough, and Elizabeth Garrett formed the Kensington Society its object, as another member Mary Westlake went onto explain was to serve as a link between women above the average thoughtfulness and intelligence to discuss common subjects. It was not intended to be a campaigning group or populist in any way, rather the opposite, but it was from these modest beginnings that the women’s suffrage movement would develop.

In October of that same year, Elizabeth Wolstenholme-Elmy founded the Manchester Society for Women’s Suffrage with the express purpose of lobbying Members of Parliament known to be sympathetic to the notion of universal suffrage and thereby votes for women, and two MPs in particular Henry Fawcett and John Stuart Mill.

Together with the Kensington Society they collated a petition with 1,500 signatures calling for the franchise to be extended to female householders which they presented to John Stuart Mill who agreed to introduce it as an amendment to the 1867 Reform Act whilst Henry Fawcett would speak on its behalf. As we have seen the Amendment did not pass being defeated in the House of Commons by 196 to 73 votes but the number of MP’s in the all-male House who voted in favour of it was more than merely encouraging, little could they have imagined that it would take another 50 years of increasingly bitter campaigning to achieve what appeared at the time no more than a natural progression and plain common sense.

The issue of women’s suffrage would go away however, but over the following decades grew often alongside other campaigns such as that for female property rights and equality in marriage including the right to divorce. By the 1890’s there were seventeen recognisable groups independent of one another campaigning for women’s suffrage their proliferation an indication of the growth of the movement, but their disparate nature weakened rather than strengthened their influence.

On 14 October 1997, the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) was formed to bring the various groupings together under the leadership of the veteran campaigner for women’s rights, Lydia Becker. When she died soon after the responsibility fell to Millicent Fawcett who as the sister of Elizabeth Garrett and wife of the radical MP for Brighton Henry Fawcett seemed with an abundance of experience working for her husband the obvious choice, though a certain Emmeline Pankhurst may have thought otherwise.

Millicent Fawcett being of a nervous disposition and a poor public speaker may not have appeared a natural leader but her formidable logistical and organisational skills could not be denied. The strategy she adopted however would not be acceptable to some.

Believing that women needed to prove they were responsible enough to be able to fully participate in politics she encouraged restraint and a policy of peaceful persuasion - they would disseminate their arguments by word of mouth, distribute pamphlets and lobby their MP’s, and when they did demonstrate they would do so in an orderly fashion and remain firmly within the law. There was no need to threaten anyone they had the momentum and they had right on their side - it could only be a matter of time. But how much time, they had already been excluded from national politics for too long and many of those men who wielded the levers of power had firmly set their faces against any further changes to the franchise.

On 10 October 1903, six women met at the Pankhurst family home in Manchester to form the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) whose motto would be Deeds Not Words and would for a time at least be a family affair with Emmeline Pankhurst as its leader ably supported by her daughters Christabel and Sylvia.

The founder of the WSPU had been born Emmeline Goulden on 15 July 1858, in Manchester, a burgeoning industrial city that took great civic pride in its status as the beating heart of British production and a centre of world trade, a sense of belonging shared by her radical and politically engaged parents who taught the young Emmeline to stand up for what she believed in and to hold firm against criticism. She absorbed the message and had a thirst for politics from an early age at a time when it was still thought improper for a woman to be so distracted.

In 1879, she married the barrister and strong advocate of women’s rights Richard Pankhurst, and soon after joined the Women’s Franchise League. But in many other respects Emmeline was a conventional woman of her time, Victorian in her outlook and conservative in her views. She was a believer in Empire and the status-quo who did not seek social change beyond equal rights for women. She would countenance neither socialism nor Republicanism and refrained from any talk of wealth re-distribution and like Millicent Fawcett she did not advocate the removal of the property qualification as the requirement for receiving voting rights. In doing so, she made the claim that the WSPU represented all classes a tenuous one to say the least. Indeed, the drive to engage and recruit working women was to remain a bone of contention among party members throughout the years of its existence and by the end of it was barely less middle-class than it had been at the outset.

Indeed, the WSPU was to be plagued by dispute and dissent for much of its existence both because of the tactics it adopted and its longer-term strategic aims. Many felt, while agreeing on the urgency for greater militancy and direct action, that some had gone too far and Emmeline’s refusal to curtail or even condemn the actions of some of the party’s more fanatical members was damaging the movement in the eyes of the public. It was also felt that her obstinate refusal to embrace wider social issues was alienating many who might otherwise be their natural supporters.

But you cannot be all things to all people and Emmeline was determined to keep her eyes firmly on the prize of votes for women from which she believed all other benefits would assuredly flow. As for the aggressive nature of the campaign it was the result of the real sense of injustice and the anger it aroused, a grievance that could no longer be placated by letter writing and pleas of consideration from those who were responsible for their plight. If women were to fight for their rights, then they would need to be seen to be doing so.

Even Millicent Fawcett, who vehemently opposed Suffragette tactics and was to do so publicly, had to concede their effectiveness in keeping the issue at the forefront of the political agenda and she admired their courage in being willing to accept public opprobrium, provoke the wrath of the law and to endure physical hardship for the sake of the cause.

As for Emmeline, she would not be moved and the more dissent there was the firmer the grip she took of the party which in turn saw her increasingly condemned for her autocratic behaviour. In the meantime, her Deeds Not Words would prove more than a slogan it would form a campaign strategy and the WSPU’s adoption of militant direct action which began in earnest in 1905 would continue to escalate in intensity and violence right up to the summer of 1914 and the outbreak of World War One.

It was a campaign of sustained street politics nourished by acts of illegality too numerous to detail that provoked public outrage and kept the issue firmly in the news; letter bombs were sent to prominent opponents of women’s suffrage, paintings in the National and Tate Galleries were attacked forcing the latter to close, the Tea House in Kew Gardens and similarly in other Royal Parks was burned to the ground, hundreds of mail boxes were set alight or had acid poured into them destroying their contents, Churches and Lloyd-George’s holiday home were fire-bombed, the turf at sporting venues were cut up, cricket pavilions set ablaze, incendiary devices planted at both St Paul’s Cathedral and Westminster Abbey, and a bomb was found at the Bank of England. Such was the paranoia it engendered that there were even rumours of possible assassination attempts being made on leading politicians and Special Branch was called in to investigate, but no evidence was ever produced.

But their behaviour also played into the hands of their opponents and in March 1906, the Daily Mail coined the phrase Suffragette to distinguish these Mad Women from the more respectable Suffragists of the NUWSS.

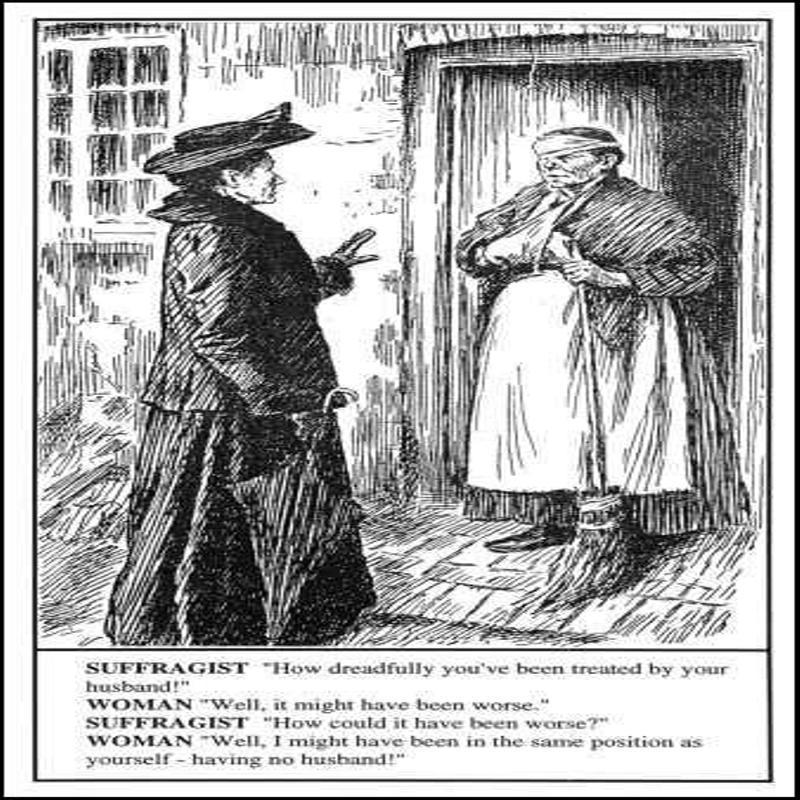

But who exactly were these women, according to their opponents they were single, childless, selfish careerists who tight-laced, tight-lipped, and poker-faced were deeply frustrated harridans who absolved of nurture were in need of a husband.

Women had been made different to men by God, it was argued for reasons of balance in a society where men would run its affairs while women would tend to its needs. The female role was a caring one and it was no accident that childbearing led to muddled thinking and if any further proof were needed that women were irrational, tended towards hysteria in times of crisis and could not be trusted with a role in national affairs then here it was every day on the streets of Britain’s towns and cities for all to see.

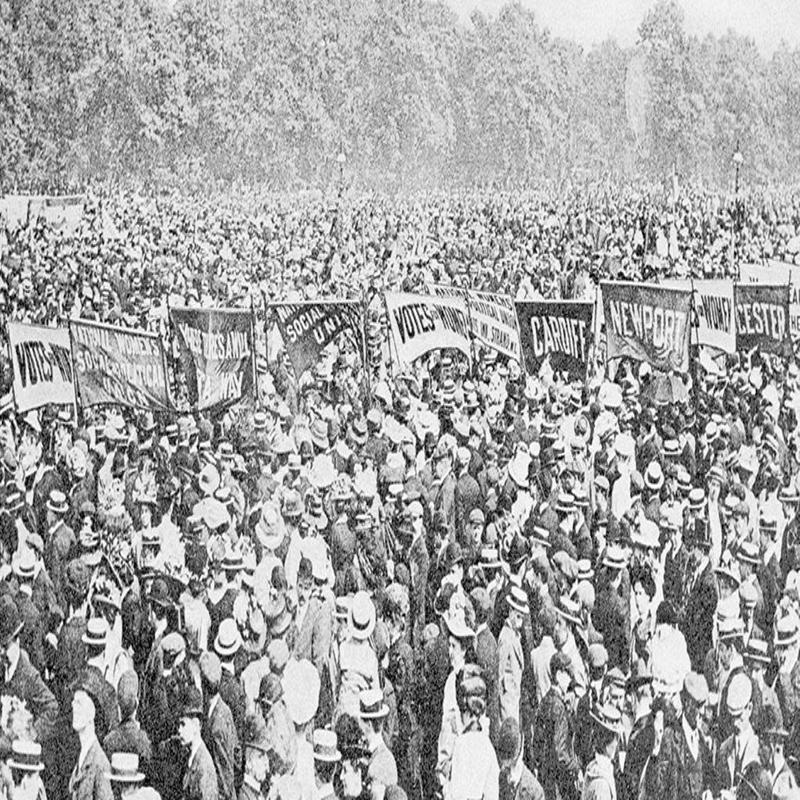

On 21 June 1908, on what was billed as Women’s Sunday the WSPU held its first great rally in Hyde Park, London as specially commissioned trains brought members and supporters from around the country in a great procession upon the nation’s capital.

As thousands descended upon the park from all different directions the vastness of the crowd made the authorities nervous that any disturbance might lead to tragedy, but they needn’t have worried for it had been well organised well and little had been left to chance. The entire day went off with military precision that if it didn’t win the argument for women’s suffrage left no doubt as to their operational and logistical expertise.

Carrying placards, waving flags, and sporting the Suffragette colours of white, green, and purple on their hats, pinned to their dresses, and on scarves around their necks it was a colourful display of purpose and determination accompanied by brass bands and bright sunshine. A great many tickets had been sold so a large turnout was expected, and it didn’t disappoint. With 8 separate platforms, 80 speakers, 700 banners proclaiming women’s suffrage, numerous stalls selling Suffragette goods and paraphernalia, vendors, and newspaper sellers it was perhaps the largest gathering of people ever witnessed in the capital city its numbers swelled even further by the curious and those simply there to jeer.

There was to be no trouble, indeed much laughter and light-hearted joshing prevailed though the issue remained a serious one and the conversations earnest but the sight of so many thousands of gaily attired women gathered in a febrile atmosphere of hope and expectation made for a glorious and intoxicating moment almost surreal in its evocation and even Emmeline’s own recollection six years later has a dream-like quality:

Never had I imagined that so many people could be brought together to share in a political demonstration. It was gay and beautiful as well as an awe-inspiring spectacle, for the white gowns and flower trimmed hats of the women against the background of the ancient trees, gave the park the appearance of a vast garden in full bloom.

The numbers in attendance can never be truly ascertained and varied greatly from 100,000 to 300,000 though as is usual in such cases the more conservative figure was generally reported by both police and press. Similar rallies took place in the other major cities including in October a march through Edinburgh that was the largest demonstration ever witnessed in the Scottish capital’s streets.

Never had women gathered in such numbers to campaign for a political cause, a show of force that made the front page of every newspaper, but it had brought female suffrage no nearer. Indeed, it seemed to have merely hardened attitudes against it and the following month, though it had been sometime in its formation, the Women’s National Anti-Suffrage League was founded. It had been conceived by the leading Conservative politician Lord Curzon as an organisation whereby those women and men opposed to women’s suffrage could actively campaign against it.

Its first President was to be the popular author Mary Humphry-Ward and on its central committee sat other such prominent Edwardians as the travel writer Gertrude Bell, the social reformer Violet Markham, the poet, and historian Hillaire Beloc, and the children’s author and founder of the Victoria League, Lady Jersey, who along with 29 other female peers had been busy in the preceding months gathering recruits and subscribers.

The anti-Suffrage League claimed that most women had no interest in politics and even less in being able to vote and that those who were seeking it were an unmarried and childless educated elite less interested in the welfare of their sex than they were the upward arc of their own careers – an accusation not entirely without foundation. A mere glance at the core leadership of both the Suffragist and Suffragette movements and the rank indifference of most women to the issue at all did lend their claims some credence. So much so that the campaign for women’s suffrage was disparagingly referred to as Votes for Ladies!

Within a year of its foundation the anti-Suffrage League had 110 branches nationwide, 15,000 paying members, and claimed to have, though it was never proven, a petition with 320,000 signatures but in truth it never succeeded in attracting a mass following. Its meetings were also disrupted and although Mary Humphy-Ward toured extensively lecturing on the dangers of women’s suffrage the venom and vitriol with which she was often received eventually frightened her into silence.

Despite the resounding success of Women’s Sunday, the notion, if it had ever really existed, that marches, parades, and rallies would simply by the sheer numbers of those in attendance sweep all before them soon dissipated. In any case, Emmeline Pankhurst had only ever seen them as an effective means whereby to communicate the message and the gaiety of the event was soon forgotten as the WSPU resumed its campaign of disruption and intimidation.

In the meantime, Millicent Fawcett warily placed her faith in the Liberal Party from whose ranks the suffrage movement had always drawn support though only on an individual basis and she was to have several ‘positive’ meetings with the party leader and Prime Minister Herbert Henry Asquith. So, there was real hope that the General Election of February 1910, called over the rejection of the Chancellor of the Exchequer David Lloyd George’s People’s Budget would see the return of the Liberal Government and its support in Parliament for the new Suffrage Bill then being drawn up.

The NUWSS and the WSPU united to campaign for what they believed would become the moment of truth despite Millicent’s misgiving about becoming too closely associated with the militancy of Mrs Pankhurst’s Suffragettes. She wrote to her sister: We have the best opportunity by far, for women’s suffrage in the next session (of Parliament) if it is not destroyed by disgusting the masses with revolutionary violence.

The NUWSS via its many federations raised a petition with 280,000 signatures while the WSPU suspended its campaign of direct action. The Liberal Government was returned to power with a slim majority despite polling less of the popular vote than the Conservative opposition and in March the new Suffrage Bill was tabled in Parliament with the endorsement of 36 MP’s. In July, the NUWSS and WSPU held a joint rally in London to press for its passage.

But it was in the end not supported by the Government and women’s suffrage was once again overwhelmingly rejected. All the hope and expectation had been misplaced and Millicent Fawcett was left red-faced having been deceived by Prime Minister Asquith’s emollient words when in truth he had always been opposed to women’s suffrage and would continue to be so. The NUWSS though it had never had any formal arrangement now withdrew its support from the Liberals and looked instead to the emerging Labour Party for political succour even though it favoured universal suffrage without any property qualification.

The WSPU by contrast reacted to the betrayal with fury and on 18 November, a day that would become known as Black Friday Emmeline led a demonstration that would end in violent clashes with police in Parliament Square.

As some women chained themselves to the railings in Downing Street and in Parliament Square itself the police, who had received instructions from the Home Secretary Winston Churchill to take a hard-line with protesters responded accordingly; but refusing to be intimidated the Suffragettes fought back, spat upon and scuffled with police officers and the sight of women of good appearance being roughly-handled, thrown to the ground, and dragged away by the hair with torn dresses and bloodied faces was shocking to genteel Edwardian society.

The violence that day in Parliament Square confirmed in the eyes of many within the suffrage movement that there could be no further compromise, that there could be no turning back while those who opposed votes for women were gleeful, the sickening scenes only reinforced what they had been saying all along that this was a lunatic fringe of mentally deranged and psychologically disturbed women who proved with their every action that they could not be trusted to run a confectionary stall let alone have a say in affairs of state.

As the militancy escalated so did the number of Suffragettes arrested and sentenced to terms of imprisonment, but the campaign would continue whether it be in public on the streets or in private behind prison walls.

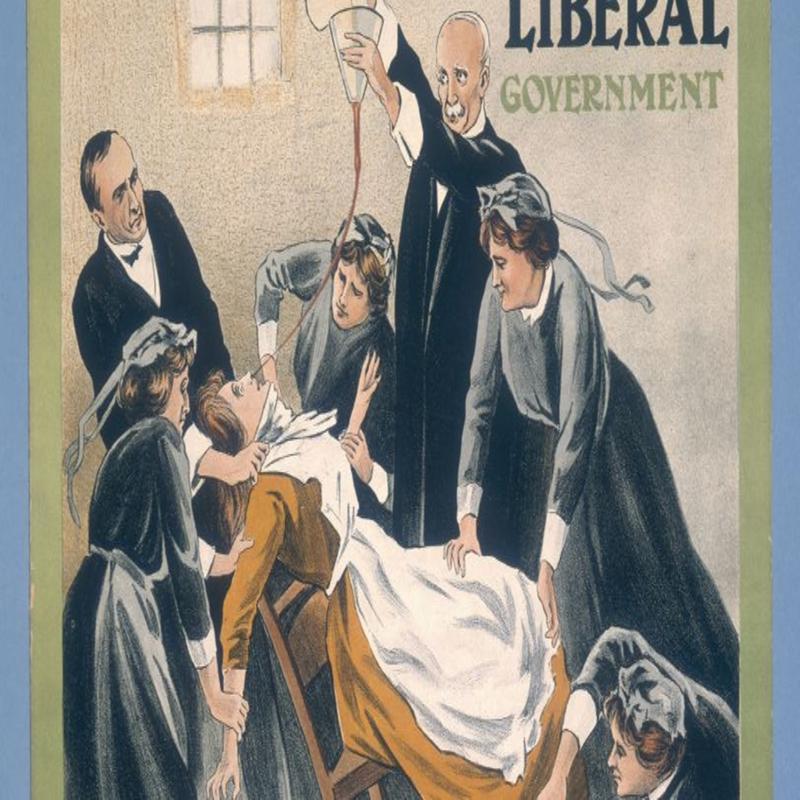

The first Suffragette to go on hunger strike while in prison had been Marion Wallace-Dunlop in July 1909, by the following year it had become part of Suffragette campaign strategy, though no one was cajoled into doing so.

The Authorities response to the dread prospect of otherwise respectable middle-class women starving themselves to death while in the care of His Majesty was swift and brutal - force feeding. If they would not eat of their own volition then they would be made to do so and the means whereby this was achieved was frightening, humiliating and painful.

As many as six people would enter a cell, doctors, nurses, and warders who would physically restrain the woman often tying her to a chair before forcing her mouth open and keeping it so with a wooden or steel gag as a tube was thrust down her throat and nutrients poured in. If the victim struggled so that this became problematic, then similar could be achieved via the insertion of a nasal tube. Some women resisted this process so violently that they became badly bruised, lost teeth, and even on occasion had bones broken. The vomiting would also be so frequent that the nurses carried scent to be sprinkled about the cell to disguise the overwhelming stench of puke laced with fear.

In 1912, Emmeline Pankhurst who had been sentenced to a short term of imprisonment for the wilful destruction of property was to write of her own experience whilst incarcerated: Holloway became a place of horror and torment. Sickening scenes of violence took place almost every hour of the day, as the doctors went from cell to cell performing their hideous office.

When it came to Emmeline’s turn, she resisted so vigorously that it was decided to spare her such indignity in the future if only to deny the Suffragette leader the propaganda value of being able to reference her own torture.

The Government was nonetheless accused of torturing women in prison and the bad publicity this engendered resounded far beyond the shores of Britain, something had to be done.

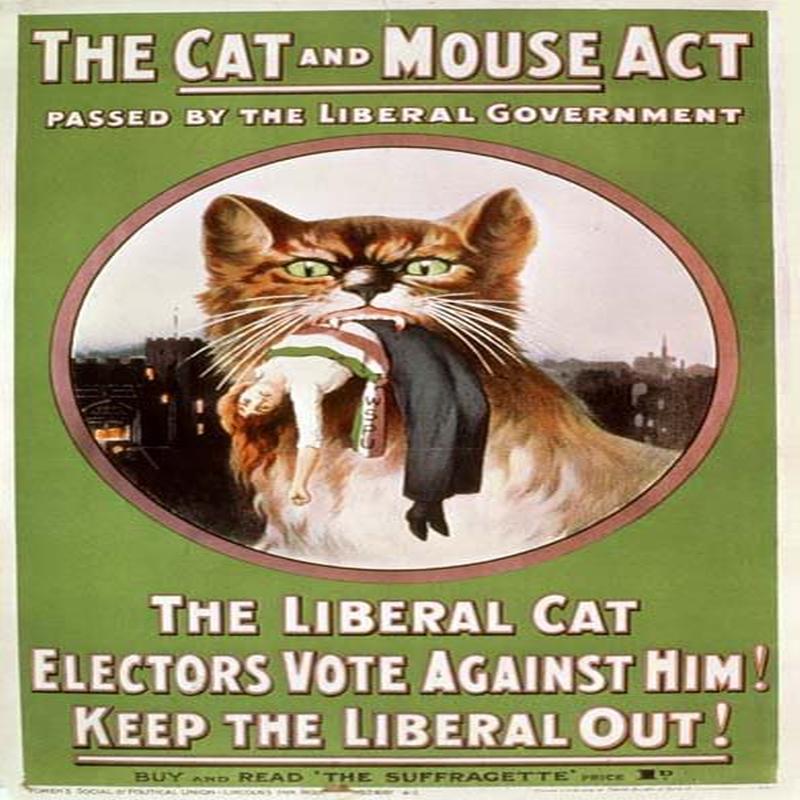

In April 1913, it passed through Parliament the Temporary Discharge for Ill-Health Act, soon to become notorious as the Cat and Mouse Act.

In future, Suffragettes who chose to go on hunger strike would be permitted to do so until their condition so weakened that it posed a threat to their health at which point they would be released to return home where it was assumed that they would eat normally again, if they did not and starved to death as a result then it was not the Government’s fault but the woman’s choice. Controversial though this was the most shocking and notorious incident in the campaign for women’s suffrage was yet to come.

June 4, 1913, was Derby Day on Epsom Downs, the most prestigious event in the sporting calendar attended by the great and the good including the King and other members of the Royal Family.

Emily Wilding Davison, a dedicated Suffragette who having already been arrested many times including for on one occasion hiding in a closet overnight in the House of Commons and had a reputation for being somewhat semi-detached and acting of her own volition was aware that the race would be shown on newsreels in cinemas the length and breadth of the country and so determined to turn it into a propaganda coup for the movement.

Emily Wilding Davison, a dedicated Suffragette who having already been arrested many times including for on one occasion hiding in a closet overnight in the House of Commons and had a reputation for being somewhat semi-detached and acting of her own volition was aware that the race would be shown on newsreels in cinemas the length and breadth of the country and so determined to turn it into a propaganda coup for the movement.

As the King’s horse Anmer, headed down the straight the last but two to pass Emily ducked beneath the railings and ran out. There was no time for Anmer’s jockey to change course and the speed of the collision brought the horse crashing to the ground and threw Emily across the turf. Her injuries were manifest, and she was to die later that night without ever regaining consciousness. The Suffragettes had their first martyr though the return rail ticket in her purse and the rosette in Suffragette colours found on her person (and which she intended to pin to the King’s horse) indicate this had not been her intention.

Even so, great use was made by the WSPU of Emily’s sacrifice, the supreme sacrifice, and a special edition of the party newspaper was printed, her image appeared on party posters, and her funeral the following week was turned into a grand procession with the coffin draped in Suffragette colours emblazoned with the slogan Deeds Not Words.

Emmeline Pankhurst wrote: Human life is for us sacred, but we say if any life is to be sacrificed it shall be ours; we won’t do it ourselves, but we put the enemy in the position where they will have to choose between giving us freedom or giving us death.

But for all this Emily Davison’s death elicited little media or public sympathy and more concern was expressed for the horse, which survived the fall, than the martyrdom of a woman who fitted all too well the popular perception of the Suffragette as isolated and friendless, a cold-blooded zealot unflinching in her beliefs heedless of the consequences of her actions - she had merely reaped what she had sown. But it wasn’t just the opponents of women’s suffrage who were shocked and appalled by Emily Davison’s behaviour, those among the NUWSS felt that it only reinforced the smear of irresponsibility and that if women kept behaving like lunatics they would continue to be thought of as such.

In response to what they considered the Derby Day Debacle the following month the NUWSS organised the Women’s Pilgrimage to show that most women not only wanted the vote and a greater say in society but were rational and reasonable enough to be trusted with such a grave responsibility. Organised by Katherine Harley, women from Federations across the country would ride, cycle, and walk to a rally in Hyde Park, London.

The Pilgrimage was not always well-received in the towns and villages it passed through and those participating often had to endure not only jeers but a hail of missiles, as one woman complained - it is not easy to feel a pilgrim when abuse is hurled at you - and in East Grinstead the marchers were attacked by a mob. As a result, many curtailed their march or rallied locally to show their support.

Unlike Women’s Sunday five years earlier the NUWSS rally in Hyde Park was intended to be a sober affair and many of the 50,000 or so present wore smart but plain clothes often in a uniform colour of blue and grey. The Times newspaper wrote: On Saturday the pilgrimage of the law-abiding advocates of votes for women ended in a great gathering in Hyde Park, the proceedings were quite orderly and devoid of any untoward incident. Indeed, it was as much a rally against militancy as one in favour of women’s suffrage.

Many bitter things were said of the militant women, that for all the blood, thunder, and appeals to justice the objective of women’s suffrage appeared as elusive as ever and all because of stupid deeds by stupid women such Emily Wilding Davison.

But everything was about to change.

The summer of 1914 was neither as tranquil nor as gloriously sunny as it has often been portrayed. It rained a great deal and a series of strikes made life miserable for many; Suffragette militancy was at its zenith and the nation’s politicians were absorbed in the crisis over Irish Home Rule that could result in civil war. Indeed, so distracted were they that the assassination on 28 June in Sarajevo of an obscure Austrian Archduke and his wife was barely noticed. But the death of princes in lands ruled by autocrats rarely pass without consequence and the diplomatic situation in Europe soon spiralled beyond the control of politicians to that of logistics, timetables, and long-term military planning. As pleas for calm were received and ignored the great nations of Europe went to war, including on 4 August, after some uncertainty and no little dithering, Britain.

Emmeline Pankhurst was a passionate supporter of Britain’s involvement in the conflict and along with her daughter Christabel, who since the previous year had taken over the leadership and day-to-day running of the WSPU she immediately suspended the party’s campaign of disruption and civil disobedience. It was a decision that did not sit well with many of the membership who already uneasy at the escalating violence of the campaign now felt railroaded into supporting an unnecessary war they felt had an Imperial dimension, in particular Emmeline’s two other daughters Sylvia and Adela, both committed pacifists.

Emmeline’s relationship with Sylvia had long been strained particularly because of her antagonism towards the Labour Movement. Indeed, they had been in dispute for some time over Sylvia’s work with the East London Federation of Suffragettes, a predominantly socialist organisation of working class women. Emmeline in fact demanded that Sylvia remove the word Suffragette from their name. When Sylvia refused, she reacted angrily: You are unreasonable, always have been and I fear always will be. I suppose you were made so.

Sylvia, on her part, could not understand how her mother who had once been a Poor Law Guardian and had witnessed the extreme poverty of the destitute with her own eyes and often expressed the deepest sympathy for their plight could now seemingly turn her face against them. Now she was in favour of a war that whether it was of short duration or not would still cost the lives of thousands mainly working-class young men, and for what?

Moreover, her mother had made the decision to suspend the WSPU’s campaign arbitrarily and without consultation, for patriotic reasons, she said: What is the use of fighting for the vote if you have no country to vote in. Even so, it seemed yet another example of her increasingly autocratic manner and dictatorial behaviour.

When at a rally an audience member dared to question her support for the war Emmeline accused her of being pro-German, a traitor, and demanded that she be removed from the auditorium. It was too much for both Sylvia and Adela who both denounced their mother.

Emmeline in turn was no less scathing of them, writing to Sylvia: I am ashamed of where you and Adela stand. Not long after Adela journeyed to Australia, she would never see or speak to her mother again.

Increasingly frosty meetings between Emmeline and Sylvia did little to smooth over a family rift that would never be truly healed.

In the meantime, activists within the WSPU campaigned vigorously in support of the war often adopting the same crude tactics that had been the hallmark of their campaign for women’s suffrage; attending recruitment drives where in plain sight they would turn their backs on those men they thought less than enthusiastic to enlist, white feathers would be thrust into the hands of young men not yet in uniform, and a letter writing campaign was begun to name and shame those seemingly unwilling to do their duty.

Millicent Fawcett also supported the war and much like Emmeline Pankhurst had to stand firm against a strong peace movement within her own party (indeed, most of the NUWSS Executive Board would resign over the issue) but unlike Emmeline she trod warily and did not seek confrontation neither did she encourage men to enlist or condemn those who did not.

Absorbed by the war effort and full of patriotic fervour Emmeline renamed the party newspaper, it was no longer The Suffragette but Britannia, and in November 1917 she dissolved the WSPU altogether forming in its place the Women’s Party, a more overtly political organisation that while continuing to argue for women’s rights also railed against socialism and called for the abolition of Trade Unions.

But by this time an informal arrangement with the government had been agreed and Emmeline knew the campaign for women’s suffrage had already been won. It had after all the bitter debate and street protests been war, that great engine of social change, that had provided the required dividend.

Women had rallied behind the war effort as never before and not simply by knitting socks and woollen mittens for the troops far away; they drove the trams, delivered the mail, lit the streetlights, sowed the land, and reaped the harvest, worked the mines, served on the railways, made the munitions and many other things besides. Like the men who had given their lives in the trenches of the Western Front and elsewhere the contribution of women on the Home Front, and indeed their sacrifice for many had died in industrial accidents and factory explosions, could no longer be ignored.

On 6 February 1918, while the war continued with no end in sight the Representation of the People Act received Royal Assent immediately tripling the size of the electorate from 7.7 to 21.4 million. Despite such a dramatic extension of the franchise the legislation had passed through Parliament with some ease though not without opposition by 385 to 55 votes in the House of Commons and 134 to 71 votes in the House of Lords.

It gave women the right to vote in national elections for the first time but not without restrictions and certainly not on equal terms with men: only women 30 years of age or over and who met a minimal property requirement could vote. Men by contrast received the vote at 21 years of age and in most cases the property qualification was abolished.

It meant that despite women being 55% of the adult population only 43% of them were eligible to vote. Even so, it was a reason to rejoice and hundreds of thousands of women across the country took to the streets to celebrate, the glass ceiling had been breached if not yet shattered.

Women could now also stand for Parliament and the first elected in December 1918 was the Countess Markiewicz but being a member of Sinn Fein she refused to take her seat so the honour of being the first woman to sit in the House of Commons fell to the American born Lady Astor who won a by-election the following year. The sense of triumph was palpable though many still considered it only a partial victory and would fight on.

In the immediate post-war years Emmeline Pankhurst travelled extensively removing herself from the continuing campaign for equal representation and in 1926 disappointed many of her supporters when her fear of Bolshevism and love for Empire led her to join the Conservative Party, those same people who had so vehemently opposed and maligned the very idea of women’s rights. To many on the left it continues to sour her legacy.

The final years of Emmeline’s life were to be marred by disappointment and scandal. Her bid to become a Conservative Member of Parliament, like that of Christobel before her, was defeated leaving he aggrieved at the lack of gratitude she received from female voters while she was hurt deeply by Sylvia who giving birth out of wedlock refused to keep it a family secret but instead spoke of it with pride.

Years of relentless campaigning had also taken a toll on her health and in late 1927 she retired to a nursing home. Over the following months her conditioned worsened and on 14 June 1928, she died aged 69.

A little over a month after Emmeline Pankhurst’s death on 28 July, the Equal Franchise Act eliminating the distinction between male and female voters became law and Millicent Fawcett, who in 1925 had been made a Dame of the British Empire, was in Parliament to witness the momentous day. She was to die the following year on 5 August 1929, aged 82.

Often seen today as heroines Suffragette effectiveness nonetheless remains a matter of conjecture. Like any organisation without a popular mandate that resorts to violence to achieve its ends it repelled more than it attracted, and whether it accelerated or retarded the fight for women’s suffrage is difficult to ascertain, but their commitment to the cause could not be denied.

Share this post: