The Witch-finder General

Posted on 6th August 2021

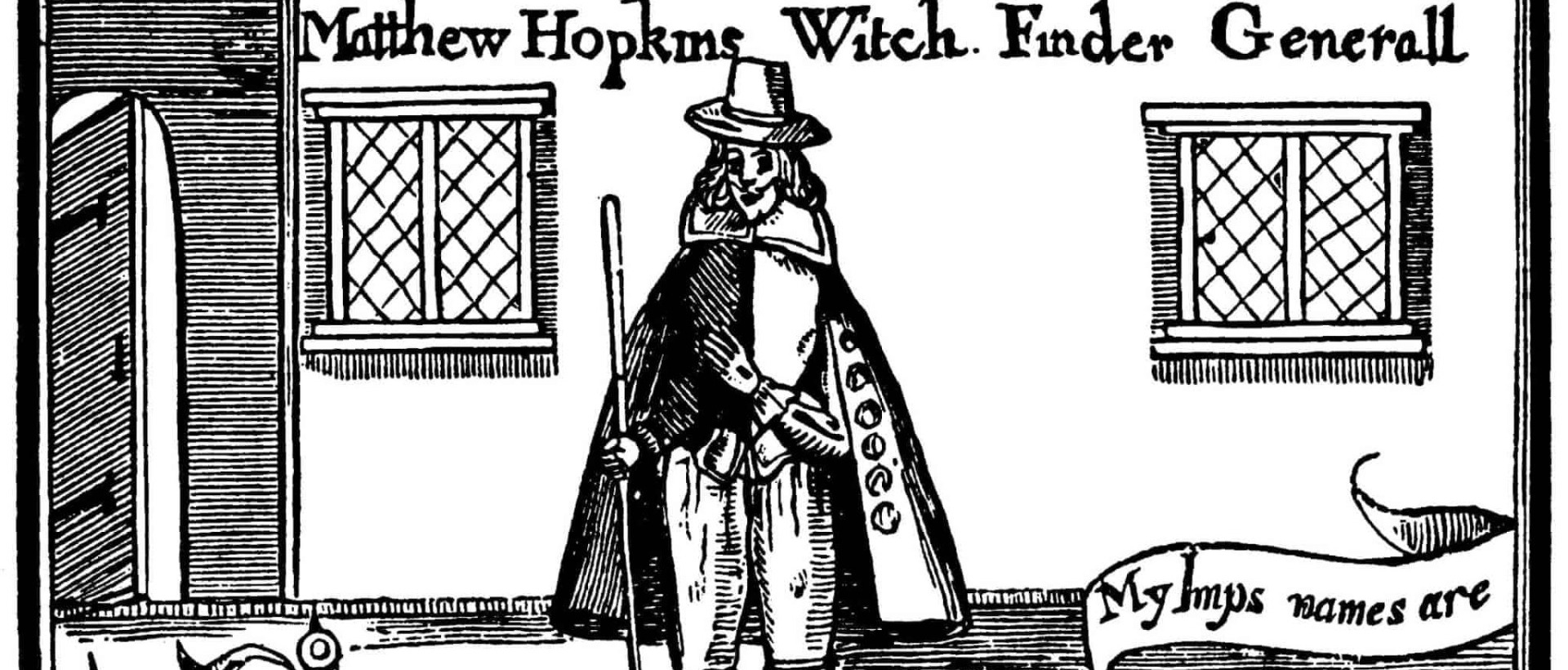

At the height of the English Civil War, at a time when the country was bitterly divided, starving, and awash with blood, a man was to emerge who would become one of the most sinister characters in all English history. Little is known about him, he simply appeared from the ether and disappeared again just as suddenly, but for eighteen months he was to initiate a reign of terror across much of south-east England – he was Mathew Hopkins, the Witch-finder General.

He was born around 1620 in Great Wenham, Sussex, though there is no actual record of his birth. His father, James Hopkins, was a firebrand Puritan clergyman but one who was popular with his parishioners. He was also a successful merchant who had strong connections to those who had travelled to America and settled in the town of Salem.

Mathew was one of six children and the fact so little is known of his formative years, and so much more is known about his siblings, has led some to believe that he may have been raised in Salem. We do know however, that by 1644 he was resident at the Thorn Inn in the village of Mistley in Suffolk and that not long after he embarked upon his mission to rid England of witchcraft.

His campaign began in March 1645, and was to last barely eighteen months but in that time, he was to be responsible for the death of more than 300 suspected witches, mostly women more than had been executed in the previous 150 years. He was to operate mostly in the Counties of Suffolk, Norfolk, and Essex which during the Civil War was an area firmly under the control of Parliament and where the Puritan remit ran unchallenged.

War breeds uncertainty, anxiety and paranoia and it was to prove fertile ground for travelling apocalyptic visionaries like Mathew Hopkins – Godlessness and witchcraft were much on people’s minds, and he was more than happy to add fuel to the fire.

Hopkins was to say he began his campaign after over-hearing a group of witches discuss an orgy, the devil’s temptation, and it seems possible that he did indeed believe in the existence of witchcraft. He always carried a book on demonology with him. His motivation, however, appears to have been money. He was paid according to how many witches he successfully prosecuted, and at 20 shillings a witch when the average daily pay for a worker was just two pence meant that it was a very lucrative business indeed.

He claimed to have a special commission from Parliament for his work which was untrue but declaring so with conviction and accompanied by his two assistants, the thuggish John Stearne and the shrewish and accusatory Mary Phillips, he travelled from town to town announcing himself as the Witch-finder General of England authorised to root out evil. At a time when much misfortune was put down to the effects of witchcraft he was easily believed.

His victims were invariably the old, the eccentric, the vulnerable and the destitute. One such was John Lowes, an 80-year-old cleric who had offended his parishioners by continuing to preach the Catholic liturgy, quite possibly because he never fully learned the Protestant one. Unable to remove him, these same parishioners paid Hopkins to come and prosecute him as a witch. He did, and he was hanged soon after.

Hopkins liked to try his victims before specially arranged Courts over which he himself presided. He enjoyed the status that officialdom gave him, even if it was the officialdom of his imagination. It was important to him to preserve the form at least of legality though there is no evidence that he had ever had any legal training.

Unlike in Europe where witches were tried for heresy, in England it was for the act of sorcery or maleficium committed for the purpose of doing harm, so it was not a requirement that the Church be involved or that the victims be burned at the stake.

Witches were believed to indulge in orgies where they would fornicate with the devil, drink blood, desecrate the cross, conjure up demons, make spells and cast the evil eye. Physical deformity, a curse from God, was believed to indicate who these people were so the elderly, poor, and infirm were always suspect.

Local people would point these people out and as physical deformity was thought a curse from God the infirm were always suspect. Hopkins would then round them up for interrogation. Though torture was by this time illegal in England, Hopkins remained heedless of such technicalities and those accused of being a witch were stripped naked and thrown into a prison cell. There was no bed and no means by which to stay warm. If at any time they dozed off, they would be awoken and forced to pace the cell until they dropped from exhaustion. Cold, hungry and exhausted the following day the interrogation proper would begin.

The suspect would be tightly bound to a chair and in a fashion that was designed to make them bleed. A search would then be made to find the ‘Devil’s Mark’, this could be a spot, pimple, boil, or wart. These were believed to be the teats from which the witches’ familiars, a dog, cat or other animal suckled. The procedure of pricking would then begin to ascertain whether the accused were a witch or not. A pin, needle, knife or other sharp object would be thrust into the mark. If the suspect did not cry out or if the wound did not bleed, then she was a witch.

Because on most occasions there was blood, and the accused did indeed scream in pain Hopkins had a retractable knife devised. The first time it was thrust into the skin the accused may well cry out in pain but on the second and third occasions she would not, she was therefore a witch. Also, to weaken their resolve the suspect would be forced to remain naked throughout the interrogation process.

Mathew Hopkins enjoyed his work. He didn’t just design new devices for the process of pricking he also found new ways to bind people that would maximise the humiliation and multiply the pain.

The third part of the interrogation was ‘Swimming’ where the accused would be bound to a chair in such a fashion that they were bent double. A man either side would then lower them into the water via a rope. If they drowned, then they would be perceived innocent. If they floated or survived then they were guilty; for this was a sign that they had rejected the baptismal water and had been saved from drowning by their master, the devil.

People soon came to dread the arrival of Hopkins in their communities for anyone who objected to his activities or tried to impede him in any way were in their turn accused of being a witch. He had, however, begun to overreach himself. He was becoming increasingly greedy and was beginning to accuse people of being witches on the scantiest of evidence.

It would in the end take the courage of one man to bring Matthew Hopkins reign of terror to an end.

John Gaule, the Vicar of Great Staughton in Huntingdonshire thought Hopkins a charlatan and made public his views. He wrote: “Every old woman with a wrinkled face, a furrowed brow, a hairy lip, a squeaking voice, and a scalding tongue, with a cat or a dog by her side, is not only suspect but pronounced as a witch.”

The people tired of Hopkins fleecing them and then threatening dire consequences should they oppose him, supported Gaule in his campaign to rid them of this Witch-finder General. Seeing that the tide was turning against him Hopkins did what all fraudsters and charlatans do, he disappeared.

So what became of Mathew Hopkins, the Witch-finder General of England?

John Stearne reported that he had died early in 1647 of consumption. If so, then the illness overtook him very suddenly. There does, however, exist a death certificate dated 12 August 1647, from Manningtree in Essex. It reads: “Mathew SM; James Hopkins, Minister of Wenham, buried at Mistley.”

There is, however, no known burial site for Hopkins and for a man who terrorised the south-east of England very little mention was made of his passing. So, did he fake his own death?

There is mention of a Mathew Hopkins in the records of the Salem Witch Trials that took place in Massachusetts in 1692. As we know Hopkins is believed by many to have been raised in Salem Town. By this time he would have been an elderly man in his early 80’s. Was this our Matthew Hopkins? If so, then it would be appropriate that the last recorded mention of him should be at the most notorious witch trials of them all.

Tagged as: Tudor & Stuart

Share this post: