Tsar Nicholas II: Last of the Romanovs

Posted on 1st October 2021

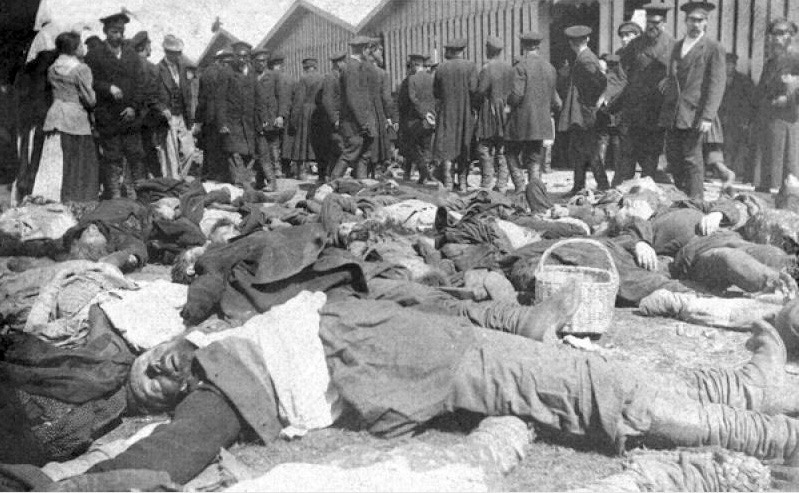

On 27 May 1896, a large crowd gathered at Khodynka Field in Moscow to celebrate the new Tsar Nicholas II’s coronation. For most Russians he was their father little short of a God and they were eager to usher in the new reign with many clearly intoxicated and boisterous.

Yet despite the vast numbers in attendance no effort had been made to police the crowd and more were arriving all the time. With the space available increasingly restricted tragedy was looming but still the police stood aside and did nothing. Eventually, someone stumbled, more followed, and panic set in. As people fought one another to avoid the crush they only made the situation worse. By the end of the day hundreds had been killed, trampled and suffocated to death. The official figure was 1,389 dead many of them children - the true figure may have been much higher.

Informed of the tragedy the Tsar was advised not to attend the French Ambassadors Ball being held in his honour that same night out of respect for the dead, but he refused to cancel the engagement. From the very beginning of his reign then, the new Tsar was perceived as being indifferent to the suffering of his people.

The subsequent Inquiry into the tragedy found the Authorities to have been negligent but no individuals were held accountable and no criminal charges were ever brought. The Khodynka Field Disaster was to damage the reputation of the Tsar and no amount of aid provided to the victims of the tragedy would repair it. It was an event that seemed to precursor all that was to come in the ill-starred reign of Tsar Nicholas II as he too stumbled from one calamity to another.

Nikolay Alexandrovich Romanov was born on 6 May 1868 in the Palace of Tsarkoye Selo, just outside the Russian capital of St Petersburg. He was a frail, nervous, painfully shy child who looked up to and admired his father greatly and was doted on by his mother. But as he grew into a young man it became increasingly clear to those who knew him that he was indecisive, irresolute and lacked the character to be Tsar. Many who met him appeared to like him, but few were impressed. When his father, Tsar Alexander III died unexpectedly at the age of just 49 of liver failure, the 26-year-old Nicholas was thrust into the position of prominence he had hoped to avoid for many more years.

He was to be an Emperor, Tsar of all the Russia’s, but he'd had little, if any, formal training for the role.

His father who had little faith in his son's ability to rule and had expressed as much to his Ministers had also him provided with little formal training for the role and so from the outset, he was reliant upon others for guidance. He would listen to advice but not always act on it for he had no desire to change anything. His father had ruled as an autocrat he said, and so would he.

He may have wanted to rule as an autocrat, but he had neither the will nor the strength of character to do so. His own cousin George V doubted his ability to run a medium sized company let alone a great Empire and it was said that he based his decisions on whatever opinion was expressed by the last person he spoke to. His Empress Alexandra deeply religious, fatalistic, emotionally unstable and subject to depression did not provide the support and stability he required to alleviate the pressure he often felt himself to be under.

Not long after taking the reins of power he asked cousin Alexander: "What's going to become of me and all Russia?" His cousin could only respond "Why are you asking me you are the Tsar now".

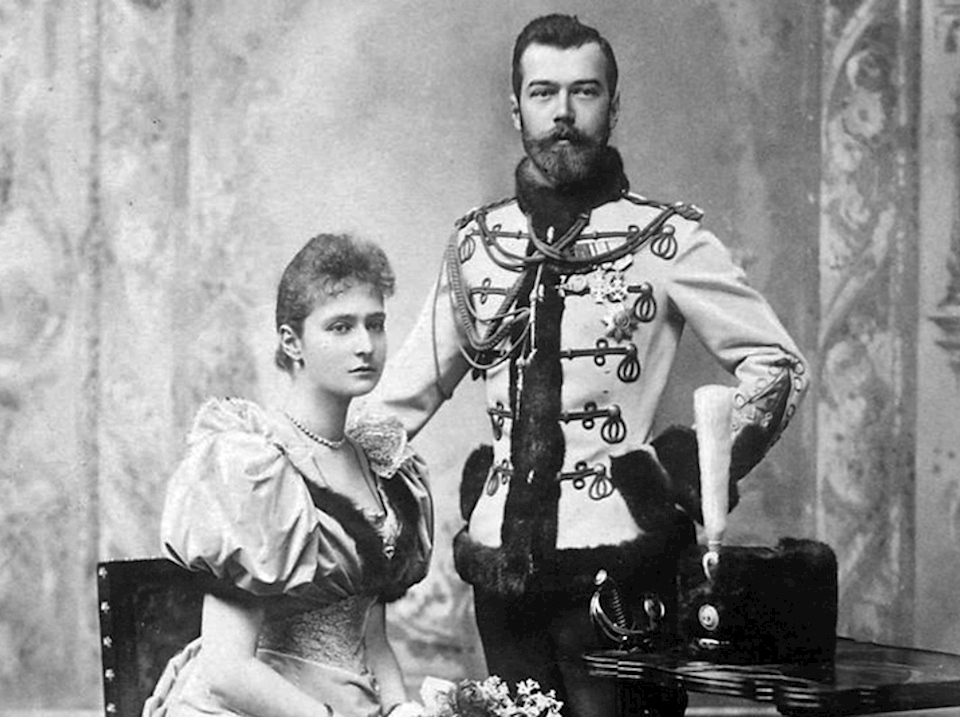

Nikolay Alexandrovich became Tsar on 1 November 1894, but his Coronation did not take place until two years later on 26 May 1896, at the Uspensky Cathedral within the walls of the Kremlin. In the meantime, he had married the German granddaughter of Queen Victoria, Princess Alix of Hesse.

Marrying a German was neither popular at Court nor with the people and she early on made a bad impression saying little of being and arrogant of manner. She did however, convert from Lutheranism to the Russian Orthodox Church which was something, and took the name Alexandra Feodorovna to make herself more acceptable to the Russian people. Few could doubt they genuinely were in love.

Tsar Nicholas who reigned by Divine Right and was therefore beyond reproach would rule as his forebears had done - as the Father of his People. He would be responsible for their welfare; he would tend to their needs but in return he expected their obedience. He would then, delegate power but he would not share it.

Physically unprepossessing being short and somewhat frail in appearance did not prevent him adopting the more masculine and coarse traits of the autocrat; he was a militarist, an imperialist, and an enthusiastic anti-Semite. He endorsed and encouraged the Jewish pogroms that swept the Pale of Settlement between 1903-06 that were to leave thousands dead and even more homeless. He also firmly believed in the Global Jewish Conspiracy as expounded in the pages of the erroneous Protocols of the Elders of Zion. He would later accept that it was a forgery and declaring that “a good cause cannot be defended by dirty means” had those copies of it in Russia pulped. He nonetheless retained his own much-thumbed copy.

Russia's aggressively expansionist policies in the Far East had brought her into direct conflict with the emerging Japanese Empire. Having behaved with a breath-taking arrogance in reneging upon a series of deals over Manchuria the Japanese at last decided they'd had enough with negotiation and on 8 February 1904, launched a surprise attack on Port Arthur on the Liaotung Peninsula.

The Russians were taken completely by surprise and could only reinforce their forces in Manchuria via the still as yet incomplete Trans-Siberian Railway. Outnumbered more than two-to-one they suffered a series of heavy defeats culminating in the surrender of Port Arthur on 2 January, 1905.

Forced to withdraw from Manchuria altogether following a crushing defeat at the Battle of Mukden in late February, their last desperate gamble to retrieve some shred of honour from a conflict they had done so much to cause ended disastrously with the destruction of the Russian Baltic Fleet in the Straits of Tsu-Shima.

The conflict with Japan had cost the Russians more than 125,000 casualties and international humiliation. It had also sparked revolution at home as Russia was paralysed by strikes, lock-ins and street protests while Workers Soviets were established in many of the major cities.

The revolution was in the end crushed by force with many of the troops mobilised having just returned from the conflict in Manchuria. It had for a time however, appeared touch and go and Nicholas had been forced to make political concessions which resulted in the issuing of his October Manifesto, a constitutional charter which allowed for the formation of a Duma or Elected Assembly.

This heralded the end of Absolutism in Russia and threatened the end of the Romanov Dynasty itself. Nicholas may have had some inkling of this for he later expressed his deep regret at having signed the document that brought it into being saying: "I feel sick with shame at my betrayal of the dynasty."

The Workers Soviet in Moscow, which had seen the emergence of the young Leon Trotsky, continued to hold out, however. Reinforcements were sent and it took two days of fierce street fighting between protestors and troops loyal to the Tsar which left over a thousand dead before it was finally crushed. When twelve years later troops were again asked to turn their guns on the workers they refused to do so.

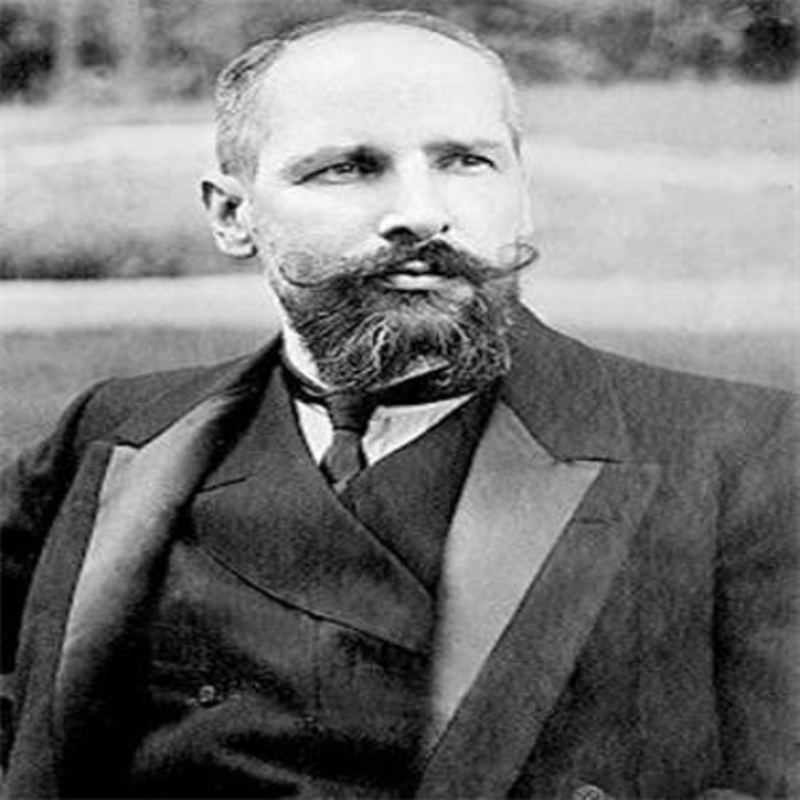

Tsar Nicholas, who so wanted to rule as the Autocrat appeared incapable of wielding the iron fist required and was to become increasingly reliant upon his Interior Minister Piotr Arkadyevich Stolypin to do so on his behalf. In July 1906, he appointed Stolypin his Prime Minister and it was he who had to take the hard line, to pick up the pieces following the chaos of the 1905 disturbances, but he also had to work with the recently elected Duma and placate those more radical members who sought reforms that that he knew the Tsar would never concede to.

Stolypin knew that reform was the only way of preserving the Romanov Dynasty and he set about trying to institute those reforms that would in time create a prosperous middle-class peasantry that had a stake in society and a reason for ensuring the maintenance of the political status-quo. This was no easy task given a deeply conservative peasantry that was firmly wedded to the old ways. At the same time, he clamped down firmly on any dissent.

Tsar Nicholas was happy to give Stolypin a free hand if it appeared that he remained the man making the final decision and the documents still appeared on his desk awaiting his signature.

On 14 September 1911, Stolypin, along with the Tsar and his two eldest daughters attended a performance of Rimsky-Korsakov's Tale of the Tsar Saltan at the Kiev Opera House.

As he watched the Opera unfold Stolypin was shot twice by the Left-Wing Radical Dmitri Bogrov. He had shouted for the Tsar to flee before collapsing to the ground. He died the following day with the Tsar weeping at his bedside.

Tsar Nicholas launched an Inquiry into the assassination but curtailed its activities shortly after when its investigations appeared to be pointing the finger of responsibility at Monarchists within the Imperial Court unhappy at Stolypin's agricultural reforms. It was yet another example of the Tsar’s unwillingness to act.

Stolypin's murder was not the first time that Nicholas had witnessed an assassination. He had been present when his grandfather Tsar Alexander II had been blown up by a bomb thrown by a member of Narodnya i Volya (The People's Will). Alexander, called ‘the liberator’ had been the great reforming Tsar who had abolished serfdom in Russia. Nicholas had seen first-hand where embracing liberal reform led - he would not make the same mistake.

Russia had ambitions to wed its great resource in manpower and land to industry and a programme of rapid industrialisation financed by Western, mostly French, money was underway but little, if no, provision had been made for the workers who were to oil the wheels of progress and the conditions in Russian factories were quite simply appalling.

Forced to work an average eleven hours a day six days a week for subsistence wages in filthy, unsafe conditions they were banned from forming associations or trade unions to represent them or fight on their behalf, and to attempt do so would lead to instant dismissal. In 1904, inflation and a scarcity of goods suppressed wages even further.

A priest, Father Georgi Gapon who was in fact a government spy but also had considerable influence among the workers of the massive Putilov Iron Works, organised a petition on their behalf to be presented to the Tsar. It was deferential in its tone and merely asked the Tsar to intercede with the employers on their behalf.

On 22 January 1905, a bitterly cold Sunday with snow lying thick on the ground, Father Gapon led a march on the Winter Palace to present the petition to the Tsar in person. Or so he thought.

Father Gapon had struck a chord and the workers gladly followed his lead with estimates putting the number at over 150,000 many accompanied by their families. Those who were present remembered how quiet the march was, how reverential it seemed with the women holding aloft religious icons and the men carrying portraits of the Tsar.

They were confident that the Tsar at least would listen to their pleas but as they neared the Winter Palace, they found the approaches had been blocked off with troops. If any warning was issued, then it was ignored for the troops opened fire and kept firing. As the protestors fled in panic Cossacks were ordered to ride them down.

According to the official figures more than 180 were killed and many more injured. The likelihood is the numbers were even higher.

The Tsar who had been made aware of the intended demonstration had ignored advice to the effect that he should meet the leaders of the march or at least address the crowd from the balcony of the Winter Palace and instead left with his family for Tsarkoye Selo. He was to write in his diary for that day: "There have been serious disorders in St Petersburg because workers came up to the Winter Palace. Troops had to open fire in several places in the city. There were many wounded and killed, how painful and sad."

The concerns of industrial workers were never to be properly addressed and serious unrest was to continue throughout his reign. One particularly notorious incident was to occur at the Lena Goldfields on 4 April, 1912.

The Lena Goldfields was situated to the north-east of Lake Baikal on the Lena River near Irkutsk in Siberia. The environment was harsh, wages low, and a working day up to sixteen hours. Also, a large percentage of the worker’s wages were paid in coupons that could only be exchanged at the Company's own stores where the goods for purchase were often of poor quality and the food rotten and inedible. On 29 February 1912, what had first started as a walkout became a full-blown strike.

The workers quickly organised and on 4 March they presented their employers with a list of demands including an 8-hour day, a 30% increase in wages, the elimination of company fines and an improvement in the quality of food made available. The Company refused to even discuss them. Instead, on 3 April the Authorities ordered the arrest of the strike leaders.

The following day 2,500 miners and their families descended on the Chief Prosecutors Office demanding their release. Troops sent by the Tsar to restore order barred their way. When the miners refused to disperse as ordered, Captain Trenschenkov, in command, gave the order for the troops to open fire. Within minutes 270 miners lay dead with a further 250 wounded.

Many high-ranking Government Officials and members of the Imperial Family were on the Company's Board of Directors. An Inquiry into the massacre was ordered but no one was ever found culpable or punished for what was described as a tragic event.

The Lena Goldfields Massacre and the lack of action on the part of the Authorities not only created a public outcry but also helped to revive revolutionary activity following the repression of 1905.

Weighed down by the responsibility of power and his wife’s constant demand “be an autocrat Nicky” he took solace in his children and the placid domesticity of a family life so far removed from tiresome politics and the drudgery of officialdom. He was a good father, if not to his people, then at least to his own children.

On 28 July 1914, war broke out in Europe, and like all the combatants Russia entered into it with the enthusiasm borne of a swift victory. For the first time in his reign the Tsar enjoyed popular acclaim and he absorbed it with uncritical delight. But Russia she was ill-prepared for war.

The much-vaunted Russian steamroller with its limitless manpower was greatly feared but with inadequate rolling stock mobilisation was painfully slow and they soon found that with munitions manufacture almost non-existent they were unable to equip the men they had called up - many had no rifles while the artillery lacked shells.

But confidence remained high and adopting tactics that had barely changed since the days of Napoleon the opening weeks of the war saw the Russian Army sweep triumphantly into German East Prussia, but early successes was soon followed by catastrophic defeat at the Battles of Tannenberg and the Masurian Lakes which saw them forced into a long and bitter retreat in the face of better organised, better armed and better led opponents. But it was no rout and by the summer of 1915, just a year into the war stubborn Russian resistance had seen them lose a staggering 1,400,000 men killed and wounded.

Faced with this never-ending cycle of defeat the Tsar dismissed his cousin Grand Duke Nikolai Nikolaievich and took personal command of the army. This was more of a symbolic gesture than anything it being felt that the troops would fight better for the person of the Tsar, but it was to have dire political consequences.

The Tsar's Headquarters at Mogilev were a safe distance from the front but too remote from St Petersburg, since renamed Petrograd, for him to influence events in the capital. Instead, the Empress Alexandra Fedorovna would govern in his absence, and she never doubted her right to do so interfering relentlessly in the administration of the country.

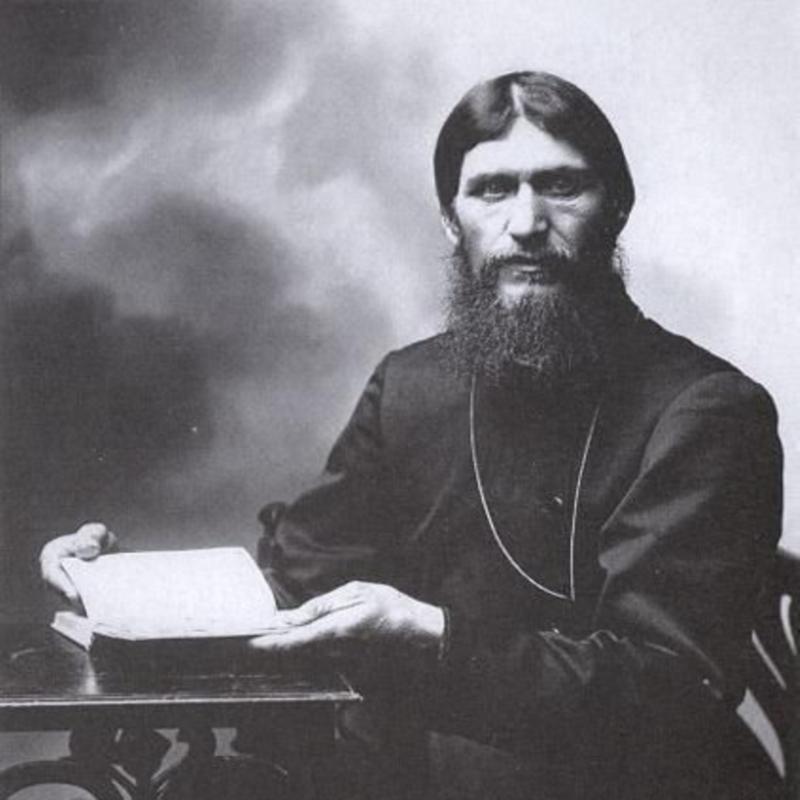

More heartily disliked than the Tsar ever was her German background made her a figure of suspicion. Moreover, she was rumoured to have fallen under the spell of the notorious Grigori Rasputin.

Rasputin was a monk from Siberia who had a reputation as a healer. He had travelled to St Petersburg upon learning that the young Tsarevich was seriously ill determined to gain access to the Imperial Court.

The Tsarevich Alexei was indeed ill, being a haemophiliac, a disease he had inherited from his mother’s ancestral line. It prevented his blood from clotting which meant that whenever he cut or injured himself, he was in serious danger of bleeding to death. The doctors had no cure and struggled to cope.

The Empress was frantic and deeply religious, when a spiritualist friend of hers brought the healer Rasputin to her attention she insisted that he be permitted to see her son.

Rasputin, described by those present as unwashed and smelling like a goat, breezed into the Tsarevich Alexei's bedchamber and demanded that all the doctors and servants present be dismissed. Then sitting beside the Tsarevich he placed his hand upon his brow and spoke quietly to the boy. Within a few hours his fever had subsided, and his health began to improve - it was a miracle, this simple peasant Holy Man had succeeded where all of the doctor's with their medicines and potions had failed.

As far as the Empress Alexandra Fedorovna was concerned he had been sent by God and for the rest of her life she would be in awe of Rasputin, his every utterance believed, his every misdeed forgiven.

On the evening of 16 December 1916, Grigori Rasputin, the spiritual healer and Mad Monk who was rumoured to be the lover of the Tsarina was murdered, not by a mob, or a lone assassin, but by a small group of feckless aristocrats.

He was lured to the home of the homosexual Prince Felix Yusupov, whose own advances towards the enigmatic, unwashed Rasputin, had been spurned, on the pretext of meeting his wife said to be the most beautiful woman in all of Russia and the prospect of an orgy. Once there he was fed a cocktail of wine and cakes laced with cyanide. These failed to kill him, however, and he finally had to be shot, strangled, and thrown alive into the Neva River where he drowned.

He had been in fear of his life for some time and just a few weeks before his death had written to the Tsar warning him: "If it is your relatives who wrought my death, then no one in your family, that is to say, none of your children will remain alive for more than two years. They will be killed by the Russian people." His assassins were indeed related to the Tsar.

Upon hearing of Rasputin's murder, the Empress went into a paroxysm of grief and rage demanding that Nicholas have the murderers arrested, tried for treason and executed. But Nicholas would not hear of it.

In the months preceding his murder Rasputin had wielded unprecedented influence in the Imperial Court and in the Governance of Russia. He took bribes, made strategic decisions and both appointed and dismissed Ministers at will. The Empress, in awe of her Holy Man did nothing to curtail his activities and deferring to him in all things effectively made him the de-facto ruler of the country. His murderers had believed that only his death could save Holy Russia from ruin.

The Tsar, who was never as much in thrall to the enigmatic Rasputin as his wife was complained to her repeatedly about Rasputin's influence at Court and he did for a short time exile him, but he would not stand up to wife and when she demanded Rasputin’s return he consented. The simple fact was he didn’t know what to and was happy to wash his hands of politics completely if he could.

In personal command of the army the Tsar could no longer blame its failings on others and deference within its rank and file was beginning to break down. Meanwhile, in February, 1917 a wave of strikes swept Petrograd bringing it to a stand-still.

Despite the severity of the weather and widespread hunger tens of thousands of workers took to the streets many carrying communist and chanting revolutionary slogans. These were no longer the icon bearing petitioners of 1905. They were no longer requesting the Tsar intercede on their behalf but demanding he abdicate.

When the demonstrators refused to disperse troops were ordered onto the streets to restore order. But there was now a breakdown of deference of frightening proportions and when ordered to fire upon the demonstrators the troops refused. Some Regiments simply returned to their barracks, but others killed their Officers and joined the demonstrations. Time was running out for the Romanovs.

By early February 1917, all authority had effectively broken down and many of Russia's major cities were in turmoil. Workers had taken to the streets, shops not boarded up were looted, and factories had ceased production.

Those troops who had been expected to restore order had not done so and many had handed over their weapons to the demonstrators. Even the Tsar's own Lifeguards had deserted to the other side.

The Chairman of the Duma Mikhail Rodzianko had wired numerous and ever more frantic telegrams to the Tsar begging him to return to Petrograd and form a new Government as the only way of saving the Dynasty. They went unanswered.

In the power vacuum that resulted from the Tsar's silence the Duma formed its own Provisional Government to work alongside the recently formed Petrograd Soviet of Soldiers and Workers Deputies. Its first act was to place the Cabinet and the Royal Family under house arrest.

Upon hearing the news that his family had been taken into custody, Tsar Nicholas was shocked and was at last prompted to act. He ordered Cossack Cavalry to advance on the capital and withdrew Regiments from the front-line in preparation for re-taking the city by force if necessary. In the meantime, he made haste for Petrograd.

Learning that the railway line he intended to use was under the control of the revolutionaries he switched to one that was controlled by General Nikolai Ruzzki, the Commander of the Northern Armies but upon his arrival at Ruzzki's Headquarters he received a frosty reception. The General curtly informed him that he now took his orders from the Provisional Government and that he had received no orders to permit the Tsar to continue his journey to Petrograd.

On 15 February, Tsar Nicholas sent a telegram to the Executive Committee of the Duma and its new leader Prince Grigori Lvov granting them permission to form a new Cabinet. In return he received a telegram from the previously loyal Rodzianko demanding his immediate abdication. The Tsar, at first dismissed the telegram saying: “That fat Rodzianko has sent me some nonsense.”

But as the reality of the situation dawned on him he declared that he had been betrayed by those he had previously thought loyal, and refused to sign any abdication document. He was adamant that the Romanov Dynasty would not cease to exist under his watch.

But on further reflection he realised that all effective power had already been wrenched from his grasp and fearing for the safety of his family, he agreed to abdicate in favour of his son, the Tsarevitch. This however the Provisional Government and the Duma would not agree to.

So instead, he abdicated in favour of his brother the Grand Duke Michael, but Michael would not touch the poisoned chalice until the decision had been endorsed by the people in a popular vote. Even so, the abdication stood and the Romanov Dynasty that had ruled the Russian Empire for more than three hundred years had ceased to exist.

The now ex-Tsar and his family were placed under house arrest on the orders of a Provisional Government that was now dominated by the ambitious young lawyer, Alexander Kerensky. He was soon to have the Romanov's, as they were now known, evacuated to Tobolsk in the Urals, supposedly for their own safety, though the truth was that he did not know what to do with them.

The Imperial Family were at first well-treated retaining their servants and many trappings of the Court while Nicholas himself was confident that his cousin King George V would grant him and his family asylum in Britain.

He was shattered to learn that the inexplicable decision to refuse his asylum request had been made and wired to the Government in Petrograd. In the meantime, Kerensky's determination to prosecute the war much as before was to have disastrous consequences for both Russia and the former Imperial Family.

His catastrophic offensive of July 1917, when much of the Russian Army simply melted away and went home was to lead directly to the overthrow of the Provisional Government a few months later.

The October Revolution and the seizure of power by the Bolsheviks under Lenin, was to change everything for the Romanovs.

The Bolsheviks were professional revolutionaries untainted by sentiment or nostalgia. To them the Romanov Family were criminals, no more, no less, and they would be treated as such. As long as they remained alive, they would serve as a rallying point for the forces of reaction.

In April 1918, they were removed to the Ipatiev House in Ekaterinburg. Here they were kept under armed guard and their every move was monitored. They were also denied luxuries such as coffee and cigarettes and were forced to eat soldier’s rations.

The Tsar's daughters were subjected to a stream of sexually charged innuendo and lewd remarks from the guards while sexually explicit drawings adorned the walls of the courtyard. The Tsar, however, was treated with greater respect and he was allowed to retain his uniform.

Strangely, the now ex-Tsar appeared to be enjoying his time under arrest. The weight of responsibility had been lifted from his shoulders it seemed and always a much better family man than he was a Tsar he was spending time with his children whom he tried to cheer up with stories and anecdotes, though he worried for their safety and that of his wife who had descended into a lugubrious fatalism. He tried very hard to ameliorate the bitterness she freely expressed towards their gaolers as it upset the children.

By mid-July gunfire could be heard in the distance and seemed to be getting closer with the passing of every day. It was the Czech Legion of the anti-Bolshevik White Army closing in on Ekaterinburg and the prospect of the Romanov's liberation began to loom large. It was to seal their fate.

On the afternoon of 27 July, ten members of the Cheka, the Bolshevik Secret Police, arrived at the Ipatiev House. They reported to the man in charge Yakov Yurovsky, who was heard to say: "Then we must shoot them all tonight."

In the early hours of 28 July, Yurovsky sent for the Tsar's doctor, Eyvgeny Botkin, and told him to rouse the Imperial Family. When the Tsar demanded to know why they had been dragged from their beds in the middle of the night, Yurovsky told them that they were being taken to the basement for their own safety. They were also to line up to have their photographs taken to show to the world that they were still alive and being taken good care of.

Once they had all gathered in the basement the Tsarina requested a chair for herself and the Tsarevich, and chairs were duly provided. Her daughters, all carrying small pillows, then gathered around her.

With the family all together posing as if they were about to have their portrait taken, Yurovsky called in the men from the Cheka and addressing the Tsar directly announced that they were all to be shot on the orders of the Executive Committee of the Urals Soviet. No one from among the Royal party or their servants uttered a sound, and it was said that you could hear a pin drop.

At last, the Tsar stepped forward as if to say something when Yurovsky gave the order to open fire. Nicholas and Alexandra died almost instantly but the Royal children did not.

Unknown to their executioners they had sewn jewels into their clothing that prevented the bullets from piercing their bodies. So they were to bludgeoned and bayoneted to death instead. The young Tsarevich was dispatched personally by Yurovsky with three bullets to the head.

Following their execution, the bodies were taken from the house to a nearby forest and placed into pits before being covered in sulphuric acid in a crude attempt to dispose of the evidence.

When this failed the bodies were removed and thrown down a mineshaft, before finally being sealed in a tomb.

Those who died in the Ipatiev House were:

Tsar Nicholas II aged 50

Empress Alexandra Feodorovna aged 46

Grand Duchess Olga aged 22

Grand Duchess Tatiana aged 21

Grand Duchess Maria aged 18

Grand Duchess Anastasia aged 17

Tsarevich Alexei aged 13

Botkin, the Family Doctor

Trupp, the Tsar's Valet

Demidova, the Maid

Kharitonov, the Cook

Share this post: