Unit 731: A Vile Contagion

Posted on 30th August 2021

On 9 July 1937, the Japanese Empire used an incident at the Marco Polo Bridge in Eastern China as a pretext for war but after a series of swift victories against a large but poorly armed Chinese Army the Japanese invasion began to stall.

As Chinese resistance stiffened Japanese casualties began to mount including some 70,000 killed and wounded during the bitterly fought three-month siege of Shanghai.

On 13 December, the Japanese Army went on the rampage following its capture of the Chinese capital of Nanking taking out their frustrations in a brutal assault upon the civilian population and hundreds of thousands were killed some doused in petrol and set alight, others beheaded or bound and used for bayonet practise. Images of the massacre, not just of men murdered but women and children also were secretly shot, smuggled out of the country and shown to shocked audiences around the world.

Indeed, such was the level of atrocity that even the Nazi Government in Berlin felt obliged to intervene to try and stop it.

The ferocity exhibited by the Japanese Army in Nanking, even taking into account a strong racial element, indicated more than anything a sense that they had bitten off more than they could chew in invading China especially when they had more important imperial ambitions elsewhere.

With the war bogged down and no end in sight victory would have to be obtained by more unconventional means.

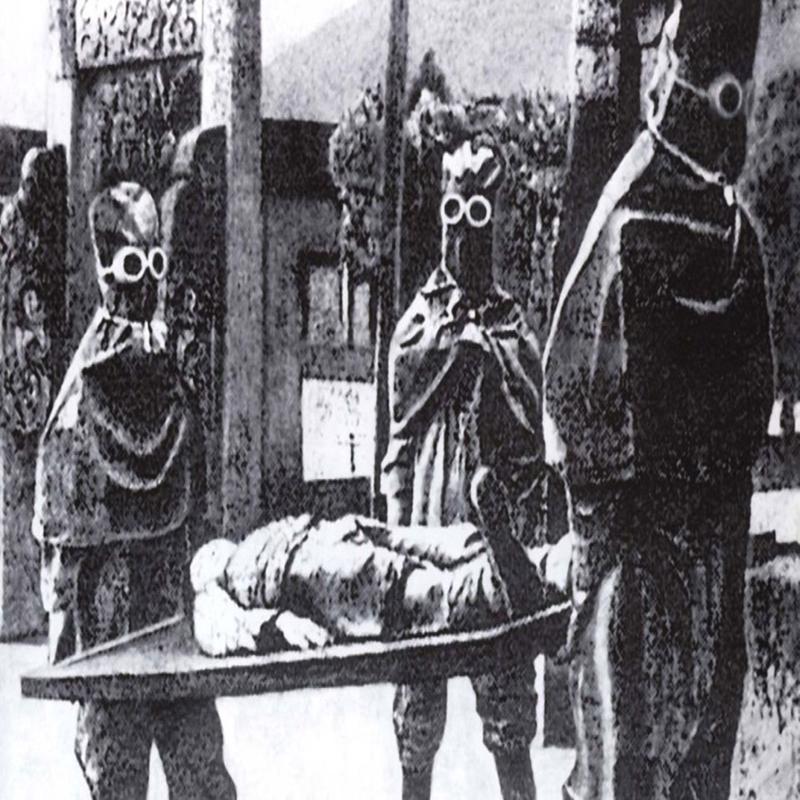

Unit 731, officially known as the Epidemic Prevention and Water Purification Department of the Kwantung Army was established by the Japanese Military Police or Kempeitai to develop biological weapons of mass-destruction for use in the war against China and later against the Western Allies in the Pacific and elsewhere. It was to be led by General Shiro Ishii, the Chief Medical Officer of the Japanese Army.

Shiro Ishii considered selfish and arrogant by his colleagues was not a popular man some even thought him emotionally unstable, but his talent could not be denied, and he had long expressed an interest in biological warfare.

Indeed, he had spent two years in the West studying the effects of the poison gas used in the First World War. His studies were well received by his superiors back in Japan and upon his return he soon found willing sponsors and financial backing.

When Unit 731 was formed Ishii seemed the obvious candidate to run it and he was excited at the prospect of having free rein to continue his experiments and the unlimited resources with which to do so, especially the continuous supply of human materiel.

In 1925, Japan had refused to sign the Geneva Convention which outlawed the use of biological weapons in warfare. Not legally bound by any International Convention they felt free to experiment at will and many within the military thought that if the Western powers wanted to ban biological weapons it was because they did not want the Asiatic nations to be in possession of something that could threaten their dominion over them.

Neither were they bound by the rules of the Convention regarding the treatment of prisoner’s-of-war who having surrendered the Japanese thought beneath contempt and unworthy of life.

Unit 731’s compound near Harbin in northern China was vast with 150 separate buildings covering an area of 6 square kilometres and employing 3,000 staff - and Ishii was eager to begin his work.

Ishii’s victims were to be prisoner’s-of-war those deemed politically suspect who were amply supplied by the Kempeitei and any local civilians rounded up at his request. The local Chinese he considered to be racially inferior, and they were regularly referred to as Logs rather than as people.

The laboratories at Harbin were not the only place where human vivisection and biological experimentation took place, Unit 731 had branches elsewhere carrying out similar work, neither were their activities a secret.

Shiro Ishii regularly addressed symposiums in Tokyo and was rewarded for his work by Prime Minister Hideki Tojo in person. Likewise, film of Unit 731’s experiments were shown to members of the Imperial Family and Emperor Hirohito’s brother Prince Mikasa actually visited the Compound at Harbin.

The worst of Unit 731’s atrocities were committed at Harbin where experiments undertaken with enthusiasm by Shiro Ishii, if not always by the doctors working under him some of whom expressed shock at what they were expected to do, became one vast Chamber of Horrors.

Victims were subjected to vivisection without anaesthesia with limbs severed to study blood loss whilst other procedures included the injection of women with diseases such as syphilis and gonorrhoea, the forced aborting of pregnancy to study the foetus, whereas others were strung up by their heels to see how long it would take them to choke to death.

Prisoners-of –War were also used to test the effectiveness of weapons often tied to a post with explosives attached and blown up, burned alive with flame-throwers or repeatedly stabbed with germ infected bayonets.

Those captured Chinese soldiers not already executed or employed in forced labour would be marched in columns and subjected to poison gas attack.

Ishii was eager to see the results of his experiments put into practise and devised plague bombs containing cholera, typhoid, and anthrax to be dropped on densely populated areas of China with similar weapons used to destroy crops and pollute water supply.

Chemical weapons were in fact deployed extensively by the Japanese throughout its war in China with Ishii’s preferred weapon the Bacilli and Flea Bomb which dropped from the air in ceramic canisters were designed to spread Bubonic Plague.

However, more than 1,700 Japanese troops also died as a result of germ warfare, and this posed a major problem for Ishii because he could not guarantee in what direction or to what extent these diseases would spread determined as they were by a simple change in wind direction. As a result, they could not be used in close proximity to Japanese held territory or on the front-line and as such they became primarily weapons of terror.

Most of Unit 731’s victims were Chinese and Korean but Russian prisoners-of-war and captured western soldiers were also subject to vivisection and biological experimentation.

Major Robert Peatty, a British Officer, reported that whilst incarcerated in a prisoner-of-war camp near Mukden, Japanese doctors from Unit 731 arrived and took away 168 American prisoners they claimed for reason of vaccination – they were never seen alive again.

On another occasion in May 1945, the 8-surviving crew of an American B-29 Super-fortress shot down over south-eastern Japan were taken to Kyushu University where doctors from Unit 731 operated on them while they were apparently both still alive and conscious. It is also claimed that western prisoners were subjected to live amputation and organ removal at camps in Thailand and Singapore but the evidence for this remains unverifiable.

There are also more than 1,100 recorded incidents of the Japanese using chemical weapons against Chinese troops in zones of conflict including at the Battle of Changi where it is believed thousands were killed as a result.

Ishii deemed his use of germ warfare a success and wished for them to be adopted in the Pacific against the advancing Americans but fear of retaliation on a much larger scale from the United States saw this idea shelved. In the final months of the war however with Japan close to defeat and their cities under intensive aerial bombardment the decision was made to take the war to mainland America.

Operation Fugo, or Wind-ship involved launching balloons designed to carry both incendiary and explosive shells high into the atmosphere to be carried by the jet stream across the Pacific Ocean to land on the West Coast of the United States.

Once again Ishii, who still had ambitious plans for his weapons programme pressed for them to be armed with plague bombs to spread disease, destroy crops and wipe out livestock. His request was denied.

Of the 9,000 balloons launched only 300 ever reached America where the only casualties were a woman and 5 children killed on a church outing in Oregon when they went to investigate the strange balloon that had just fallen from the sky.

In August 1945, the Soviet Union invaded Manchuria and Japanese resistance quickly collapsed.

Ishii, desperate to destroy the evidence of Unit 731’s activities ordered the compound at Harbin to be dismantled and burned. The remaining 150 prisoners he had executed and his staff he swore to secrecy and issued with cyanide tablets in case of capture.

Despite Ishii’s best efforts to conceal Unit 731’s very existence the Americans were already aware of its activities and were eager to obtain for themselves the scientific evidence that had been accrued.

In late August, following the dropping of America’s own weapons of mass-destruction on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan formally surrendered.

In the meantime, Ishii had fled back to Tokyo where he not only faked his death but in an example of the showmanship of which he was often accused arranged his own elaborate funeral. But he was not a man to whom anonymity came easy and in January 1946, he was apprehended and placed under arrest.

Not long after General Douglas MacArthur now the supreme authority in Japan dictated a memo: “The value to the United States of Japanese Biological Warfare is of such importance to (our) national security as to far outweigh the value accruing from a war crimes prosecution.”

Shiro Ishii was never charged with any wrongdoing and no member of Unit 731 appeared before the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal.

In 1948, a deal was struck that provided immunity from future prosecution to Shiro Ishii and his staff for full disclosure of the results of their experiments with Unit 731, although 12 doctors captured by the Russians were prosecuted and sentenced from between 2 to 25 years in a Soviet Labour Camp.

For handing over detailed documentation relating to Unit 731’s activities and working on Americas own Biological Weapons Programme Shiro Ishii was permitted to live openly in Tokyo and pursue his academic and scientific career.

He died on 9 October 1959, of lung cancer, aged 67.

He spent his final years working with children.

Tagged as: Modern

Share this post: