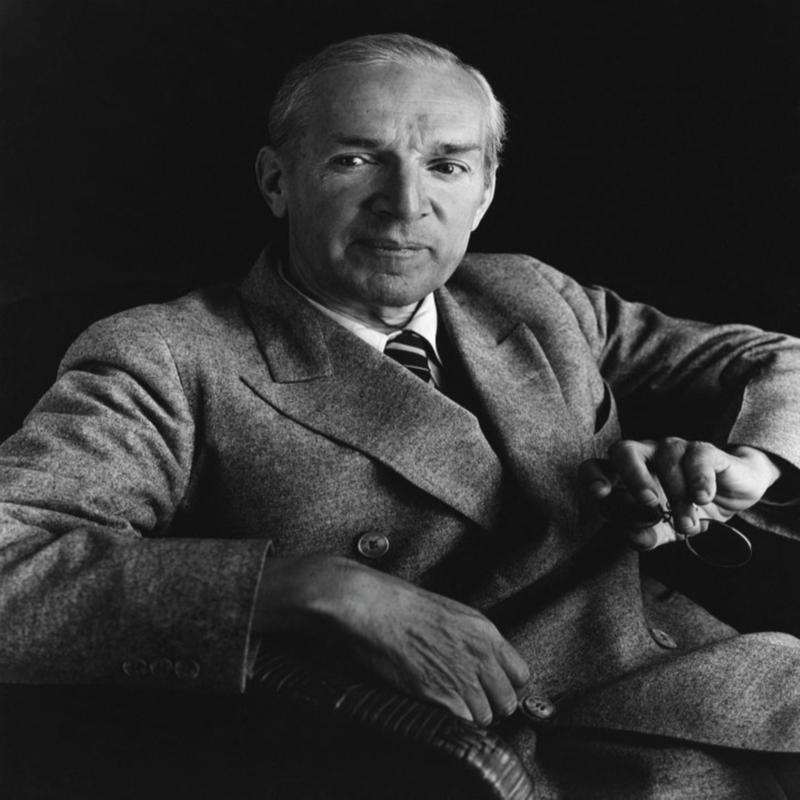

Upton Sinclair: A Socialist Governor for California

Posted on 16th February 2021

Upton Beal Sinclair was born in Baltimore on 20 September 1878. His father was an alcoholic who could not hold down a job and the family were often so poor that the young Upton was for the most part raised by his wealthier grandparents, and he was later to say that it was this early experience of the extremes of wealth and poverty that first made him a socialist.

From an early age he displayed a precocious talent as a writer and was already having his articles published in magazines and journals while still in college. Indeed, he was so successful that he was able to purchase an apartment, pay his was through university and help out his family financially.

Following a series of meetings in the autumn of 1902 with prominent left-wing intellectuals and an extensive reading of the works of Karl Marx the always politically engaged Sinclair decided to devote himself to Socialism.

As much an investigative journalist as he was an author in 1906 his novel The Jungle, in which he exposed the dire conditions prevailing in the Meat Packing Industry and its exploitation of immigrant workers, caused such an outcry that it was claimed he more than any other cajoled Congress into passing the Pure Food and Drug and Meat Inspection Act.

Despite the book being a best seller, he was disappointed that the controversy it had caused was not about the low pay, long hours and general abuse of the workers but the shock at the filth and lack of hygiene in the preparation of the meat. He somewhat despairingly remarked: “I wished to appeal to their consciences but instead won over their bellies.” Nonetheless, it proved his big break.

Sinclair was eager to become politically active but soon found that success in one sphere of public life did not always transfer to another. In 1922, persuaded to stand as the Socialist Party candidate for Congress in industrialised New Jersey he polled just 750 votes.

He was not discouraged however and four years later ran for Governor of California. Again, he was to find that a high-profile did not necessarily harvest many votes at election time and he received just 45,872 out of a total of 1,143,238 ballots cast. His experiences in New Jersey and California convinced him that no one who professed himself to be a socialist could hope to be elected to a position of power and authority in America. He would run for Governor of California again but this time it would be on the Democratic Party ticket.

The idea of California as the Land of Milk and Honey was already well-established by the 1930’s, a view only reinforced by the glamour and glitz of Hollywood but it was to prove no more immune to the degradations of the Great Depression than anywhere else; but it should be declared Sinclair for there was no excuse for poverty in California, a State where surplus food stocks could regularly be seen piled up and burned or dumped in San Francisco Bay.

Despite his poor performance in the Election of 1926, California was in fact a State where socialism in the form of co-operatives and collective communities where people bartered goods and services and shared produce on a not-for-profit basis had already taken root. By 1934, there were 176 such co-operatives in Southern California where the poor and unemployed worked together to create sustainable communities.

Sinclair now looked to take this movement State-wide in his End Poverty in California or (EPIC) programme, and to promote it he wrote the pamphlet ‘I, Governor’ in which he detailed his plans for the State and outlined what California would look like under an Upton Sinclair Administration. For example, abandoned farms and idle factories would be appropriated and given over to the unemployed to work as not-for-profit co-operatives. It was an idea that at a time of great distress in large parts of the State caught the imagination of many and ‘I, Governor’ quickly became a bestseller. It also appeared to chime with the collaborative ethos of President Franklin D Roosevelt’s New Deal for the American People. Sinclair’s programme had struck a chord and his campaign for the Democratic Party nomination took off as he became known as the – Man with the Plan.

Taking the industrious Bumble Bee as its symbol EPIC clubs now began to spring up the length and breadth of the State and its newspaper EPIC News was soon selling 500,000 copies a week.

President Roosevelt had recently passed legislation removing the restrictions placed on the formation of trade unions and a wave of strikes had followed as workers asserted their new-found industrial muscle and one of those cities in turmoil as a result was San Francisco where the Longshoremen had been on strike for two months. On 5 July 1934, the police tried to break the picket-line that had effectively closed the port and in the ensuing violence two men were killed and 73 injured. In response, and maintain the peace, but many saw it as a deliberate attempt on his part to break the Republican Governor Frank Merriam called out the National Guard, he said to restore law and order strike. In sympathy with the Longshoremen workers downed tools, shops closed their doors, the transport system ceased to run, and the city was effectively closed down for the best part of a week.

Merriam, who had not been elected Governor but had succeeded to the post in his role as Lieutenant-Governor when his predecessor James Rolph died in Office the previous month, was not a popular man. He was an old-style conservative in a State which despite having voted Republican for the previous 35 years had always considered itself as innovative and progressive. Many doubted that he was up to the job and his clumsy handling of the strike that saw troops and tanks on the street of San Francisco only seemed to confirm his detractors in their view. There was no doubt that in any election he would be vulnerable, and his behaviour had given a boost to the EPIC campaign which had previously been seen as a largely rural phenomenon by providing it with traction in the industrialised regions of the State that it had previously lacked.

In the meantime, Upton Sinclair’s campaign to be the Democratic nominee was sweeping the State and by August more than 1,000 EPIC clubs had been established and EPIC campaign volunteers had registered so many new voters that for the first time in California’s history there were more registered Democrats than there were Republicans. It was becoming increasingly likely that Sinclair would win the nomination, but he still had to win over moderate Democrats if he wished to capture the State Party Machine. So, he chose as his running-mate the mainstream Democrat Sheridan Downey earning the ticket the nickname ‘Uppey and Downey’ but his selection of Downey did not as he had hoped to placate the Democratic Establishment in California who remained wary of his so recent socialist past, something he had done little to disavow. They were disinclined to lend their support and National Committee Chairman James Farley wrote to President Roosevelt on their behalf requesting that he publicly declare against Sinclair, but he chose instead to keep his own counsel.

On 28 August, Upton Sinclair won the Democratic nomination in a landslide with 436,000 votes more than twice as many as all his opponents put together. But he knew that to maintain unity within the party he would have to compromise on some of his more radical proposals and many of his more fervent supporters were to experience early feelings of disenchantment as a result.

Returning from the Convention a clearly exhausted Sinclair was asked by a waiting reporter if he believed the unemployed and dispossessed of America would flock to California were the EPIC Programme to be implemented? Sinclair replied: “I told Harry Hopkins in Washington that if I’m elected half the unemployed would come to California and he would have to make plans to take care of them.” It was intended as a joke, but it was one that amused few and would come back to haunt him time and time again.

By the 1930’s the United States was the only major power in the Western Hemisphere that had no system of social security. There was no help for the old, the sick, the unemployed other than that provided by charitable organisations. These may have proved adequate at times of prosperity but during the worst economic slump then known to history they were simply overwhelmed. In the wake of the Wall Street Crash of October 1929, soup kitchens became a common sight in most towns and cities across America and were the only source of sustenance for millions of men, women, and children. If for no other reason the sight of long lines of idle men with pinched unshaven faces in filthy clothes begging for a handout was an embarrassment for the richest and most powerful country on earth.

President Roosevelt wished to eradicate not only such transparent poverty, but the stigma attached to it and so determined to pass the first Social Security Act in American history but the New Deal platform on which he had been elected two years earlier had been opposed at almost every turn and his proposal of a system of social security had already come in for intense and sustained criticism. He was accused in both Houses of Congress of seeking to implement socialism by the back door.

It was felt by many within the Roosevelt Administration and the National Democratic Party that Upton Sinclair’s campaign in California was jeopardising not only any future social security legislation but the entire New Deal Programme. There was a genuine fear within the Democratic Party that they would lose the mid-term elections leading to a Republican majority in both Houses and thereby leaving the New Deal dead in the water. The party wanted to distance itself from Upton Sinclair while he believing he needed Roosevelt’s endorsement to secure victory in California was insisting upon an audience with the President. It was granted, but reluctantly and only if he agreed to keep the details of the meeting confidential.

They met in private, not at the White House but Roosevelt’s home in Hyde Park, and it was a meeting Sinclair was to describe as the most fascinating two hours of his life, but no endorsement was forthcoming just vague promises from Roosevelt that he would do so in one of his future fireside chats.

The continuing unpopularity of Governor Merriam, the success of the EPIC campaign in setting the political agenda, and opinion polls suggesting a comfortable Sinclair victory alarmed the rich and powerful of California of who were at last induced to act and none were more powerful than the Movie Moguls of Hollywood.

Sinclair had suggested that redundant movies sets should be used by unemployed actors and technicians to make not-for-profit movies which posed a direct threat to the major Hollywood Studios. He had also vowed to raise State taxes for the rich.

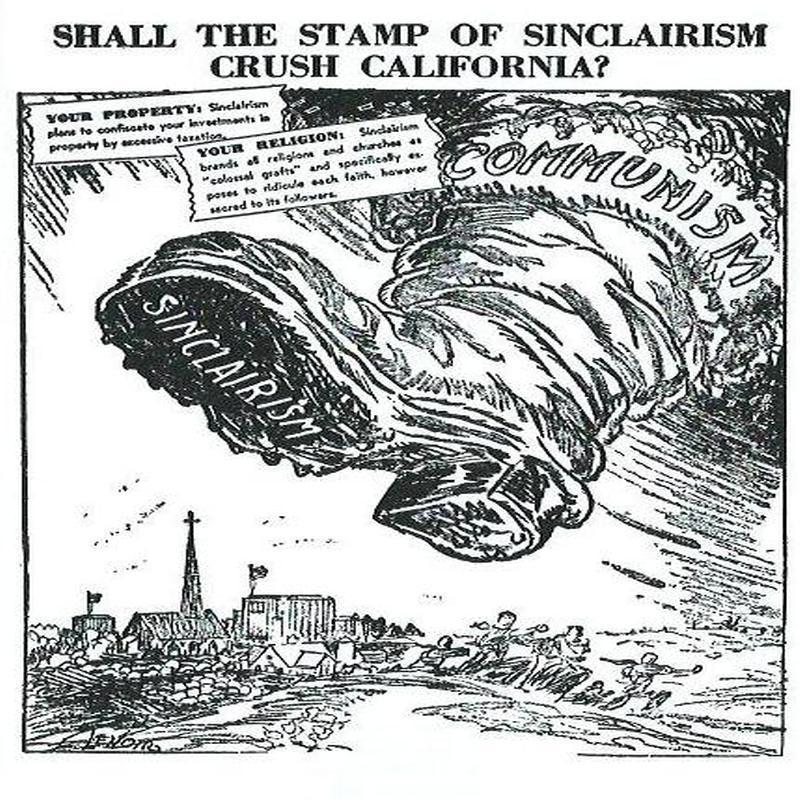

In September, the owner of MGM Studios Louis B Mayer, and Los Angeles Times owner Harry Chandler along with leading industrialists met with prominent Republicans in Los Angeles to devise a strategy to stop Sinclair. Funds were raised and for the first time in American political history an Advertising Agency was hired to run the campaign. Soon a relentless stream of negative advertising appeared on billboards, in newspapers, and cinemas denouncing the EPIC programme.

Sinclair had proposed that a paper currency known as ‘scrip’ should be used in the co-operatives and his opponents were quick to pounce pronouncing that he intended to abolish money in California replacing it with a barter system, that wages would no longer be paid in dollars but with notes of exchange, and that a person’s savings would become worthless overnight. If Sinclair wanted to abolish money they said, then he must also wish to see the abolition of private property. They even produced their own version of Scrip in the form of a dollar bill called the ‘Sincliar’ with the liar underlined and carrying the motto ‘Endure Poverty in California.’ Sinclair, they said, wanted to return California to the Stone Age.

Every day in a box on the front page of the Los Angeles Times would appear a quotation supposedly by Upton Sinclair attacking America’s most cherished institutions – marriage, religion, private property, law and order. They were in fact mostly comments made by fictional characters in his novels but were portrayed as being direct quotations from the author himself. Cartoons not just mocking the EPIC programme but warning of its threat appeared in magazines and journals and were freely distributed across the State.

In cinemas before the main feature a newsreel was shown pertaining to be impartial but in fact sponsored by Louis B Mayer that interviewed ordinary Californians to elicit their views on the forthcoming election. Those spoken to by the so-called ‘Inquiring Cameraman’ who advocated support for Sinclair were often from outside the State, incoherent in their speech, or declared themselves to be Communists or atheists.

Despite lacking the resources to respond in kind the EPIC campaign continued to grow. Their newspaper was by now selling 2 million copies a week, the national press was never as hostile to Sinclair as that in California, and he even appeared on the front page of Time Magazine. His supporters also remained confident believing that President Roosevelt would endorse Sinclair by saying something positive about their programme of production for use not profit.

They gathered expectantly around their radio sets to listen to his final fireside chat before the election, but no endorsement came. Instead, unknown to them, the leading Californian Democrat J.F.T O’Connor had approached Sinclair and asked him to step aside in favour of the third-party candidate, Raymond Haight. Despite the polls that now showed him trailing Merriam by a significant margin, he refused.

The following day O’Connor had a meeting with Merriam and told him that if he would declare a by-partisan victory and publicly endorse the Presidents New Deal, then the Democratic Party in California would endorse his campaign and advise its members to vote Republican. Merriam, agreed.

Ignored by the President and abandoned by the Democratic Party, Sinclair nonetheless fought on campaigning tirelessly and refusing to countenance defeat declaring that the support of the ordinary people of California would propel them to victory. But with Sinclair in abeyance, his opponents now began to turn the screw.

The fear of many Californians already enduring hardships was that their State would become a magnet for the dispossessed of America. After all, hadn’t Upton Sinclair suggested as much? The ‘Inquiring Cameraman’ now turned his attention on the hobos riding the trains into California – that surge of wretched humanity trailing poverty in their wake determined to cast the dark shadow of deprivation upon the Land of Sunshine and Opportunity. Those interviewed made it plain their intention was to remain and then send for their relatives should Sinclair win the election and the EPIC programme be implemented.

Despite the unrelenting hostility he encountered in interviews, the sustained negativity of the media and the increasingly gloomy poll forecasts Sinclair remained cheerful and upbeat. On 2 November, the eve of the election he broadcast an appeal over the radio directly to the voters of California: “The issue of the campaign is can they fool you with their lies and get you to vote in their interests instead of your own. It’s up to you.” But the following day as the election results rolled in the pollster’s predictions were confirmed: Frank Merriam retained the Governorship of California winning a clear majority – 1,138, 629 or 48.87% of the vote to Upton Sinclair’s 879,537 or 37.75% of the vote. The third-party candidate Raymond Haight polled 302,519 or 12.99% of the vote. When he ran again four years later his vote fell by more than 250,000. His increased share of the vote in 1934 is now believed to have been the result of mainstream Democrats advised not to vote for Sinclair and being unable to bring themselves to support Merriam. Had they voted for Sinclair, the official Democratic Party candidate then the election result would have been on a razors edge.

As it transpired, the Roosevelt Administration need not have been concerned with the outcome of the mid-term elections as the Democrats won 70% of the seats in both Houses of Congress. The New Deal was secure for now.

Although, 27 EPIC candidates won election to the California State Legislature the great social experiment of production for use not profit would never be implemented and ceased to dominate the political agenda. Upton Sinclair would never run for public office again, but his writing career continued to flourish and in 1943 he won the Pulitzer Prize for his novel Dragon’s Teeth.

He died on 25 November 1968, aged 90.

On 14 August 1935, President Franklin D Roosevelt signed into law the Social Security Act which for the first time provided 46 million Americans with access to old-age pensions, disability benefits, and unemployment cover.

Tagged as: Miscellaneous, Politics

Share this post: