Verdun: Hell on Earth

Posted on 21st April 2021

Although the onset of war in late July 1914, appeared to take many by surprise it had in fact been a long time coming and all the major protagonists had plans well in place for just such a scenario – bold strategies intended to vanquish their enemies in just a few weeks of swift but intense martial glory.

France had its Plan 17, an advance en-masse upon the lost provinces of Alsace and Lorraine with the fury of the assault sweeping all before them and propelling them into Germany itself.

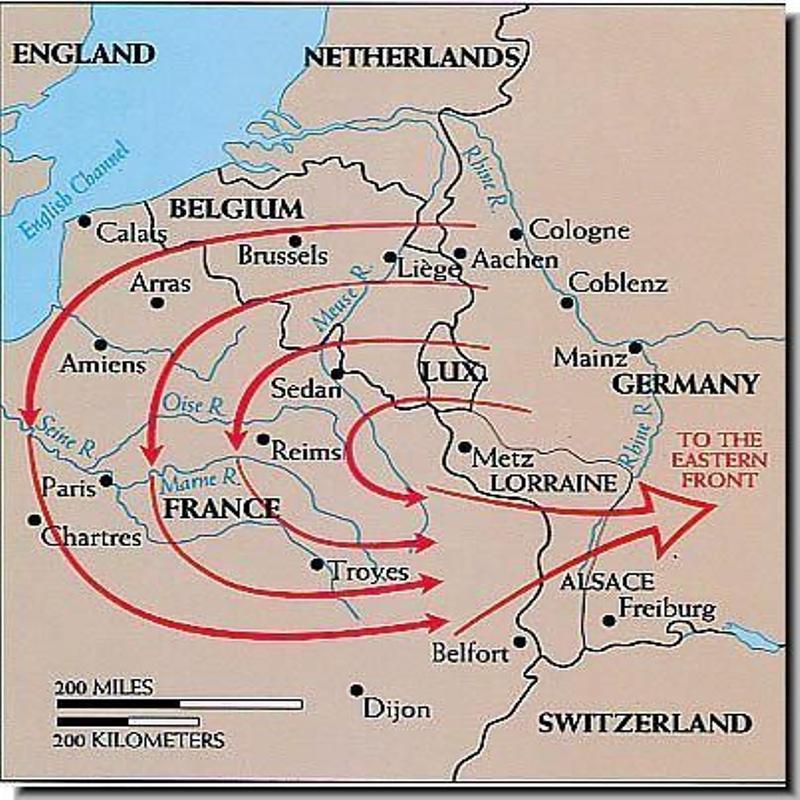

Germany by contrast had its famous Schlieffen Plan which had correctly anticipated that any future conflict in Europe would embroil Germany in a two-front war, in the West against France and the East against Russia. Believing the latter to be the more formidable opponent the Schlieffen Plan was designed to defeat France in just six weeks before the Russians could fully mobilise; so, two great armies would advance through Belgium and into France itself encircling Paris from the West and pinning the French Army on its Eastern frontier. But despite the French Plan 17 having played into German hands and been bloodily repulsed the Schlieffen Plan had likewise stalled on the Marne in September and been rolled back.

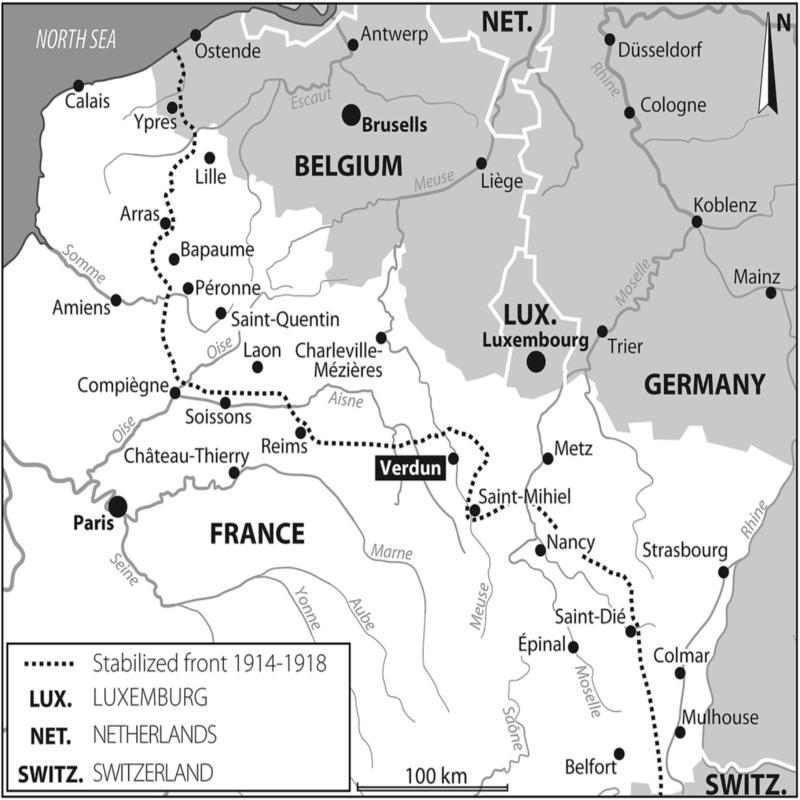

Shocked by the casualties and scale of destruction both sides now dug-in and by the winter of 1915 the mobile warfare of those early months had become a distant memory as a line of trenches protected by barbed wire and machine guns stretched from the Channel ports to the Swiss frontier scarring the landscape and dominating the battlefield. Various attempts at finding a breakthrough had since floundered in the desolate and fragmented vistas of no-man’s-land and at a very great cost in human life. Another way to break the deadlock had to be found, and the German Commander-in-Chief Erich von Falkenhayn believed that he had the formula for doing so.

Verdun in North-East France near the frontier with Germany had been a fortress town and a bulwark against Teuton aggression since the time of Louis XIV, protecting as it did the route to Paris. It had provided one of the few glimmers of hope during the country’s disastrous war with Prussia 40 years earlier and in doing so had become symbolic of French defiance and pride.

Yet those early months of mobile warfare had left the town exposed at the apex of a vulnerable salient reducing its strategic value. Indeed, its abandonment would permit the French Army to shorten and thereby strengthen their lines but given its iconic status in the collective imagination of the French people this could not be countenanced – or so believed, Falkenhayn. He told the Kaiser in December 1915:

“The strain in France has just about reached breaking point, a mass breakthrough, which is in any case beyond our means, is unnecessary. Within our reach there are objectives for the retention of which the French General Staff would be compelled to throw in every man they have. If they do so the forces of France will bleed to death.”

Falkenhayn’s intention was to capture the French front-line trenches seize the high ground and break up and destroy the French formations with overwhelming artillery fire as they approached the town. He had already made the chilling calculation that defending Verdun would cost the French five casualties for every two Germans lost. But it was never his intention to capture Verdun merely to threaten it sufficiently for the French to defend it whatever the cost and it was upon this premise that the success of his entire plan hinged.

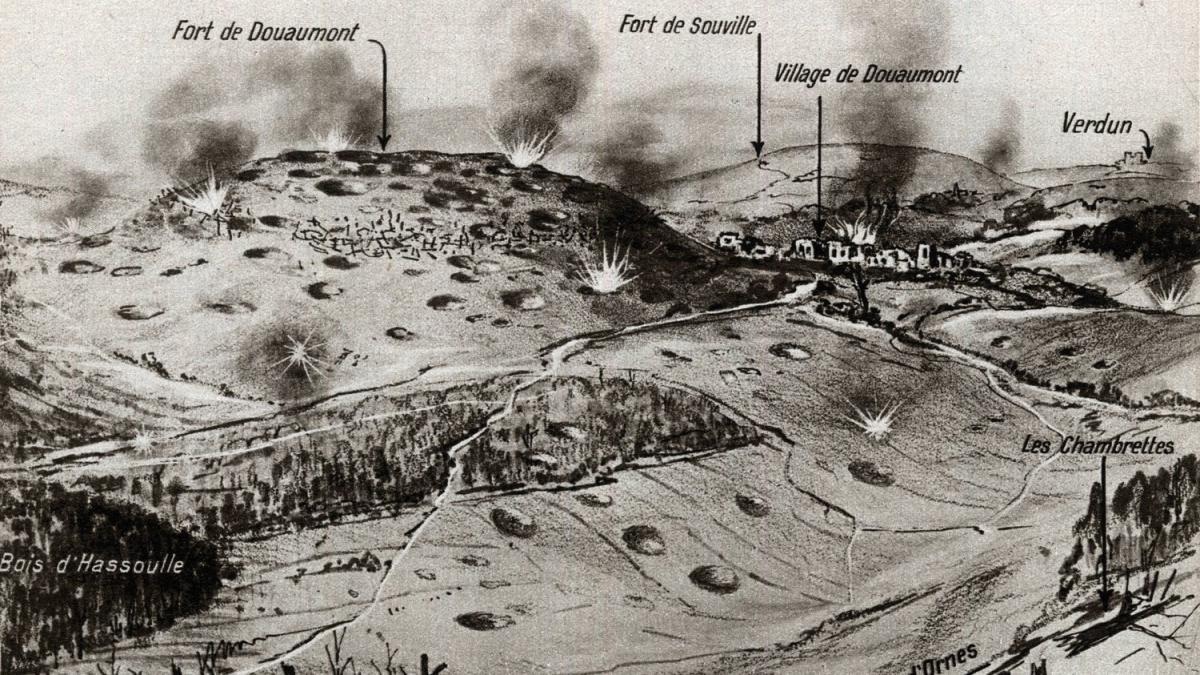

Verdun was defended by 20 large and 40 small forts the most powerful of which was Fort Douamont some 6 miles from the town and standing at the highest point for a 20-mile radius. Bristling with guns it had a concrete roof thirty feet thick to protect it from plunging mortar fire and walls similarly formidable. Surrounding it was a deep moat topped with thick barbed wire intended to trap any attacking force that would then be exposed to raking and sustained machine gun fire. Inside it was a labyrinth of corridors with gun emplacements, arsenals, storerooms, kitchens and a barracks with accommodation for 500 men.

The other forts were built according to a similar plan and along with the front-line trenches that threaded their way through the woods along the banks of the River Meuse were believed to present an impregnable barrier of concrete, steel and barbed wire. But the French High Command thought otherwise. They had seen how the Belgian forts of Liege and Namur had been swiftly pulverised into rubble by the German heavy guns and now doubted the effectiveness of such fixed fortified positions and had since been stripping the forts of guns for mobile use on other sectors of the front. Similarly, the forces around Verdun had been reduced to around just 60,000 men many of them reservists considered fit for garrison duty only.

This denuding of the defences around Verdun did not appear important for with the exception of the opening months of the war it had been one of the quietist sectors on the Western Front. It was not considered a target for attack and certainly not on a scale that would threaten it with capture. There were some however who did perceive its vulnerability.

In late 1915, the Minister of War Joseph Gallieni wrote to the French Commander-in-Chief Joseph Joffre: “Reports have come to me indicating that in the Verdun region the line of trenches appears not to have been completed. If t enemy should break though not only would your responsibility be involved but also that of the entire Government.”

Joffre replied: “Nothing justifies the fears you express in your dispatch.”

But Gallieni was not the only Officer to express his concerns.

Lieutenant-Colonel Emile Driant, a well-known author who had been a Deputy in the National Assembly prior to the outbreak of war but had re-enlisted in the army despite being almost sixty years of age used his and his political connections to warn repeatedly of the weakness of Verdun.

Driant, commanding two battalions of light infantry at Verdun, was in a position to know but such doom-laden prophecies only served to anger further an increasingly irascible Joffre and yet again the warnings were ignored.

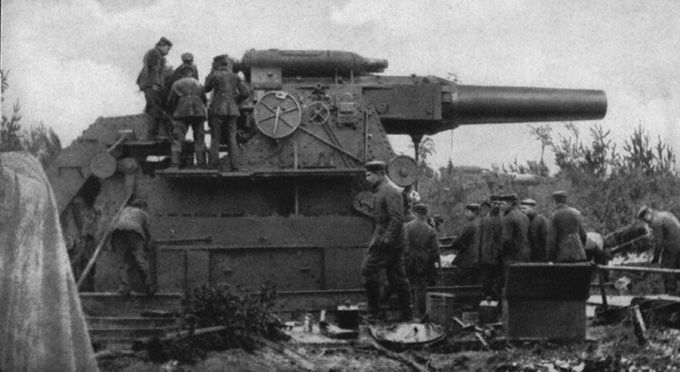

Throughout the month of December and into January 1916, the German’s increased their forces around Verdun with troops brought from other sectors while ten railway tracks were laid to bring the formidable artillery train of more than 1,200 guns – quick firing guns, naval guns, siege mortars, and heavy howitzers, along with a stockpile of more than 2.5 million shells. By the beginning of February, Falkenhayn had gathered 191,000 men and 25,000 tons of supplies.

Despite having long established air superiority in the skies over the Verdun sector the German’s nonetheless remained surprised that their build-up had gone unnoticed by the French until almost the designated time of the attack itself; but now the treacherous climate in that part of France intervened and the inclement weather and in particular the poor visibility forced the Germans to twice postpone the date of their intended assault.

At last, the French High Command woke up to the threat and though they remained ignorant of the scale and intensity of the intended assault they began to hurriedly repair and reinforce the defences around Verdun. But it was too little too late.

Operation Gericht, or Judgement, began at 4 am on 21 February 1916 with an intense three-hour bombardment of the town intended to sow confusion in the rear areas before then switching to the front-line defences.

The ferocity of the bombardment restricted to just six miles of front was like nothing witnessed before and utterly devastated the French forward defences obliterating many of the trenches entirely along with the frightened men huddling for protection within them. A survivor of that first day’s bombardment described the experience: “Men were squashed. Cut in two or divided top to bottom. Blown into showers; bellies turned inside out; skulls forced into the chest as if by a blow from a club.”

As German infiltration units armed with a fearful new weapon the flame-thrower advanced, they met little resistance greeted instead by the gruesome sight of a shattered landscape littered with body parts.

The following day the main German advance began and though some French Units had recovered sufficiently to resist they were few in number and easily outflanked. As the Germans advanced more than 10,000 prisoners were taken. That same day Emile Driant, leading his men in the defence of the village of Omes was shot through the head and killed as he came to the assistance of a wounded soldier.

The heavy guns had done their work and the Germans advanced more than three miles for the loss of just 600 men killed and wounded.

In Verdun there was chaos as French troops flooded back into the city and panic soon took hold as the rumour spread that all was lost. Now only the forts barred the way to Verdun – but could they hold out?

On the afternoon of 25 February, just four days into the campaign, soldiers of the 24th Brandenburg Regiment approached the citadel of Fort Douamont. They had no orders to capture it but meeting little resistance ten pioneers under the command of a Sergeant Kunze reached its walls where they found an open and unoccupied gun portal. Fearing that a trap had been laid for them Kunze entered the fort alone where he wandered its vast expanses somewhat lost before encountering the crew of the only gun that was firing (at targets far in the distance as it happened) he took them prisoner. He was soon joined by 130 further troops who had entered the fort by other means and together they found the garrison of 56 elderly reservists huddling for safety in one of the cellars. They did not resist.

Fort Douamont, the most powerful fortress in the world, had been captured without a shot being fired in its defence.

In Germany church bells were rung and a national holiday declared as it at last appeared that a breakthrough on the Western Front had been achieved. The Kaiser rejoiced and convinced that Verdun was about to fall visited the front to witness the devastation first-hand from a distance and through a particularly powerful and heavily protected telescope.

In France the reaction was very different, and the official communiqué published in the newspapers the following day adopted a tone of nonchalant indifference: “A fierce struggle around Fort Douamont, an advanced outpost of the old defences of Verdun, the position carried by the enemy after several fruitless assaults which cost them very heavy losses has since been reached and surpassed by our own troops.”

Few people believed it and the rumour began to spread that Paris itself would soon be abandoned.

As the German attack bore down on Verdun and it seemed increasingly likely that the town would fall the call went out for General Petain.

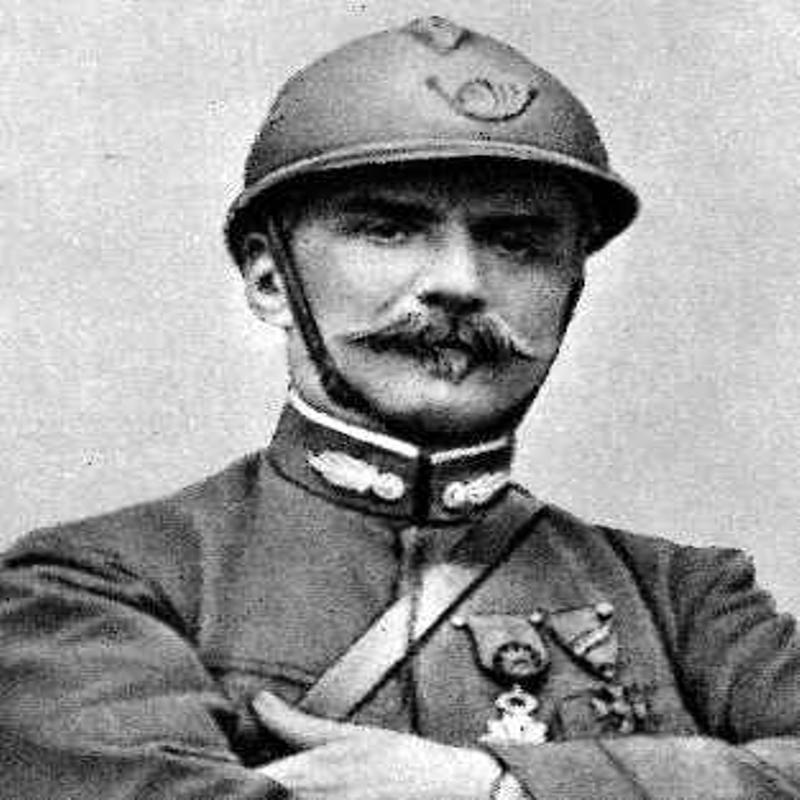

Dragged from the bed of his mistress in the dead of night Philippe Petain, the 58-year-old peasant from Northern France who had retired as a lowly-Colonel before the war but since returning to the colours had been promoted to command the Second Army at Verdun was now given the onerous task of its overall defence and of saving French pride and prestige.

Considered steady and reliable if also stubborn and if unimaginative Petain’s motto at the French Military Academy had been ‘firepower kills’ and he would not be wasteful with the lives of his men. He was also considered a logistics expert and so it would prove.

Under his command vain and costly counterattacks would cease, he ordered. They would hold what they had and if Falkenhayn sought to kill Frenchmen with his artillery then he, Petain, would kill Germans with his. In the meantime, he would begin the urgent process of reinforcement and resupply, a much harder task that one might imagine for despite its designation as a strategically important fortress town communication and transport links to Verdun were poor.

Verdun was linked to Bar-le-Duc, 50 miles to its rear by a single-track railway line and a heavy pot-holed road barely 20ft wide but it was to be this road, later named La Voie Sacre, or the Sacred Way that would become the besieged town’s lifeline.

Petain ensured that a convoy of trucks carrying troops, munitions, and supplies ran ceaselessly day and night, a truck every 14 seconds. He also organised a rotation system intended to ensure that no Unit would spend more than two weeks in the front-line before being replaced and more than two-thirds of the French Army was to pass through Verdun at some time or other. This was something that the Germans could not do on anything like the same scale and many of their troops who had been present at the battles outset would, if they survived, remain for its duration.

It was to be Petain’s mastery of logistics more than any battlefield genius or long-term strategic plan that was to save Verdun but he was also quick to recognise the value of artillery bringing their full-weight to bear on the advancing Germans who had made the strategic error of not capturing the high-ground on the East Bank of the Meuse thereby exposing their right-flank to the quick-firing French guns and despite their early successes there were tensions within the German Command Structure.

Crown Prince Wilhelm, the heir to the throne who was regularly lampooned in the British press as the ‘Kaiser’s Little Willie’ had in fact proved to be a competent Commander of the 5th Army that had launched the initial assault on Verdun struggled to grasp the strategy that underpinned it and could not conceive of ordering his men to risk their lives attacking a position it was not their intention to capture. But then a battle has a momentum all of its own and success breeds ambition.

The capture of Fort Douamont, the Kaiser’s triumphalism and the cheering of the Berlin crowd beneath the din of Church bells had undermined the entire purpose of a campaign that was intended to see the French Army commit itself to a funeral pyre of its enemy’s making. A victory has to be seen not just believed, the Crown Prince recognised this while Falkenhayn had feared it but the tension between the two men would ease for a time at least.

It would emerge once more as both armies became locked in a savage and unrelenting embrace in which neither could break free. A battle that the Crown Prince would soon insist could not be won and was a waste of German lives and resources. But it was also a battle that could not now be lost.

A combination of bad weather, stubborn French resistance and the ample and effective use of artillery had slowed the German advance but on 6 March they attacked once more and with renewed vigour in an attempt to eradicate the threat posed by the French guns positioned on the aptly name La Morte Homme or Dead Man’s Hill that had been decimating the German right-flank.

Advancing behind an artillery barrage from 25 heavy guns firing 3,000 shells the Germans met stiff resistance and made little headway as no sooner was a position taken than it was counter-attacked by the French and retaken.

The Germans withdrew temporarily to re-gather their forces but on 11 March following a bombardment that saw 15,000 high calibre mortar shells fired in short order they renewed their assault but this time on the hills to the east and west of La Morte Homme and with some success this time digging-in to consolidate their gains; but even as they did so they were raked by the very French guns the assault had been intended to eliminate.

By the end of March, the French had lost 86,000 men and it seemed as if Falkenhayn’s prediction that they would defend the sacred soil of Verdun at all costs was correct. As one French soldier wrote, “An artery of French blood was cut on February 21st, and it flows in large spurts.” But the Germans had also lost 80,000 men – the difference in the butcher’s bill was negligible.

This mutual bloodletting was not what Falkenhayn had envisaged, and it was getting out of hand. He now began to doubt the soundness of his own strategy and when the Crown Prince requested reinforcements to compensate for his losses in the recent offensive it was denied.

Following the March attacks targeted assaults and incursions continued as the battle descended into an artillery duel of unparalleled proportions and hellish intensity infernal in its design as both protagonists appeared intent upon blasting the other into extinction.

The guns thundered, the ground trembled beneath their feet, the shrieks of the dying the maimed and the endless days without food, water or sleep was unbearable; the sight of bodies unburied and uncovered were everywhere as was constant all-pervasive stench of death in a nightmare landscape of mud and blood where soldiers awaited imminent death – atomised, dismembered or buried alive: “To die from a bullet seems to be nothing; parts of our being remain intact, but to be dismembered, torn to pieces, reduced to pulp, this is the fear that flesh cannot support and which is the great suffering of the bombardment.”

Another soldier wrote: “You eat beside the dead, you drink beside the dead, you relieve yourself beside the dead and you sleep beside the dead.”

The nightmare of Verdun was etched on the face of every man forced to endure it with their morbid expressions of eternal damnation in life. Even the usually insouciant Petain felt compelled to write: “When they came out of the battle, what a pitiful sight they were. Their expressions seemed frozen by terror; they sagged beneath the weight of horrifying memories.”

Petain had stabilised the situation but the French remained under pressure particularly by the German preponderance in heavy guns and his constant demands for more men and resources when he had no plan for bringing the battle to a successful conclusion and at a time when Joffre was gathering Divisions for the Anglo-French offensive on the Somme intended for August, saw him dismissed in May to be replaced by the more offensive-minded Robert Nivelle who informed Joffre that he didn’t require reinforcements just fighting spirit.

But that fighting spirit was being sorely tested as the frozen ground and cold of winter became the rains of spring and the heat of summer. Men once fearful of frostbite now dreaded exposure to the sun and disease as flies gathered on rotting corpses and the dysentery caused by parched throats seeking hydration from whatever they could.

And all the time hunkered down in inadequate boltholes they awaited the shell that would obliterate them from history only to emerge briefly once more on the roster of the missing presumed dead. As one German soldier wrote: “Drum, fire, and bravery no longer exists only nerves, nerves, nerves.”

Nivelle, who had experienced some success on a much smaller scale but had a reputation for being wasteful with the lives of his men was eager to take the offensive once more and his target would be Fort Douamont.

On 17 May, 300 French guns began a sustained bombardment of Douamont and for five days the fort and the trenches around it were plunged into darkness as filled with smoke and choking dust lines of communication were cut, food became scarce, water ran out and sleep impossible but still these tortured, bedraggled and exhausted men would be expected to fight when the assault came, and they would, as the German soldier always did.

On 22 May, French troops assaulted the Fort determined to retake it and restore French prestige and despite sustaining heavy casualties from German small arms fire were able to penetrate and occupy a large part of it but the reinforcements sent to consolidate their gains were bloodily repulsed and those inside the fort cut off and surrounded were forced to surrender.

Nivelle’s assault upon Douamont which had expended thousands of shells, killed many Germans but had also cost the French 5,640 men changed nothing and it appeared the nightmare of Verdun was destined to continue.

Also in May, Falkenhayn, whose nerves had been seriously strained in the previous weeks, had his confidence restored by intelligence reports that the French had suffered some 500,000 casualties more than twice as many as his own army. Encouraged by, as it turned out flawed information and the failure of Nivelle’s own offensive Falkenhayn now abandoned his policy of bleeding the French white and bowed to the demands of his Army Commanders to go on the attack and crush once and for all the French before Verdun and capture the town.

As a precursor to the main assault on 2 June the Germans attacked Fort Vaux, the most powerful fort in the Verdun defences after Douamont and which despite being under almost constant bombardment since the opening days of the battle had remained remarkably intact. It was now to resist a bombardment from German heavy howitzers intended to cave in its roof. They failed to do so but they cleared the way for the German assault troops to advance upon and penetrate the fort in a number of places.

Outnumbered 5 to 1 the garrison of 600 men commanded by Major Sylvain Raynal may have been expected to surrender but instead he erected barricades inside the fort’s narrow corridors. In semi-darkness and barely able to breathe in the choking dust and fumes Raynal and his men retreated from barricade to barricade holding out for five days and only surrendering when the water ran out. It is believed that the Germans had poisoned the supply.

For the loss of 163 men killed and 191 wounded Raynal’s heroic defence had cost the German’s 2,470 casualties but Fort Vaux had been lost nonetheless and was to be the stepping-stone for the main German assault to follow.

On 22 June, after a bombardment that included 120,000 phosgene gas shells that effectively silenced the French guns the Germans were able to penetrate to within 2.5 miles of Verdun. After months of bitter struggle, it seemed that a German victory was at last within sight. Certainly, Petain thought so telling Joffre that he intended to withdraw the troops of his Second Army from the East Bank of the Meuse and that unless the British brought forward the date of their offensive on the Somme then all was lost.

Joffre who’d had to withdraw the bulk of the French Divisions that had been assigned to assist in that offensive now demanded that the British attack as soon as possible to relieve the pressure on Verdun. The British Minister for War Lord Kitchener agreed despite the reservations of his Army Commander Field Marshal Haig. In the meantime, Joffre issued an appeal to his men: “Soldiers of Verdun, upon your heroic resistance still depends our future victory. I make one more appeal to your courage, your ardour, your spirit of sacrifice, your love of country. Hold fast and strive with all your might to shatter the last desperate efforts of an enemy at bay.” At the same time General Nivelle issued his famous order of the day that would resonate throughout Europe and the World: “You shall not let them pass.”

But a temporary shortage of shells hampered the German advance and continued French resistance saw it stall. When the Germans resumed their assault on 9 July firing a further 60,000 gas shells, they found that the French had equipped their troops with the most up-to-date gas masks and that other than causing a general discomfiture the toxic fumes had little effect. The 300,000 high explosive and shrapnel shells fired had a more telling impact but failed to silence the French guns which reciprocated reaping a rich harvest in killed and maimed Germans advancing on their new target Fort Souville.

After much bitter fighting on 12 July a handful of German troops at last reached the fortress on the heights above Verdun, the last great obstacle between them and the town, and standing upon its roof could see its Church spires and deserted streets. It was a brief moment of triumph, but Souerville did not fall, the French swiftly counter-attacked, and that glimpse of Verdun was to prove the high-water mark of the entire German campaign – they would go no further.

Throughout the Battle of Verdun, the French soldier noted for his dash, elan and courage in the attack had displayed characteristics of obduracy, fortitude and a grim determination that had surprised his German enemy.

Yet again they had resisted the shelling and at close quarters and in the narrow confines of trenches that were often little more than slits in the ground they fought furious hand-to-hands battles of brutal and merciless savagery. As Corporal Louis Barthas recounted, “Woe betide anyone who fell into the hands of the enemy alive; all sense of humanity had disappeared.”

Instead of taking the town the German attack had merely created for themselves a dangerous salient vulnerable from three directions which the French were eager to exploit and Falkenhayn now halted all further offensive operations and ordered the German army to go over to the defensive. His decision to do so was not just the result of events on the battlefield but also external factors.

On 4 June, General Aleksei Brusilov had launched the great Russian offensive against the Austro-Hungarian Army in Galicia which in the first week alone took over 400,000 prisoners and not for the first time the Germans were forced to come to the aid of their ally who seemed on the brink of collapse including two Divisions of the 5th Army at Verdun. Similarly, the British offensive on the Somme brought forward to the 1 July saw the Germans fearing a breakthrough remove many of their heavy guns from the Verdun sector.

The tide of battle had swung firmly in favour of the French as the German forces at Verdun continued to be denuded of men and guns, but they were in no rush to take the initiative and for a time at least hostilities eased a little and the death rate slowed.

It wasn’t until the 20 October that the French began their offensive to drive the Germans from the area around Verdun once and for all with their first priority the recapture of the iconic Fort Douamont.

During the preliminary bombardment along the length of the German line the French fired 855,264 shells one of which penetrated Douamont’s roof and ignited in its arsenal killing 53 German soldiers and triggering a secondary explosion that killed many more in a barracks nearby.

The fighting around Douamont was fierce but seriously damaged by further shelling and with many of its guns destroyed or inoperable on 24th the Germans abandoned it. Fort Douamont which had fallen in the first week of the battle without a shot being fired in its defence and was dismissed as insignificant had been recaptured at the cost of thousands of lives but also much glory and triumphalism.

With a superiority in guns for the first time and having long ago regained control of the air the French renewed their offensive determined to finish the job.

On 15 December following a six-day barrage from 827 guns firing 1,169,000 shells the French advanced. As they did so the artillery switched to the German second line peppering it with thousands of shrapnel shells that prevented both reinforcement and retreat. The German defence collapsed and by 20 December they had been forced back 5 miles, all the forts secured, all the ground lost retaken, and 12,000 prisoners were marched with much fanfare through the shattered streets of Verdun.

Fighting now at Verdun, on the East Front and at the Somme it was the German Army that was being bled white.

In a ten-month battle of attrition that need never have been fought but for a flawed strategy based upon a calculus of death (a concept that would be repeated in Vietnam fifty years later) the French suffered around 474,000 casualties of whom some 162,000 were killed, the Germans 434,000 casualties with 143,000 killed. But such was the degree of carnage that no figure given can be considered definitive, yet even at this admittedly conservative estimate it accounts for a casualty a minute throughout the entire duration of the battle.

More than 70% of those killed and maimed at Verdun were the victims of artillery fire and during one four month period of the battle 24 million shells were fired or 2 shells every second of every day and every night.

The Battle of Verdun, the greatest clash of arms then known to mankind had ended in a French victory though some would later claim stalemate – so much destruction and death for so little gain on either side it was said. As one French soldier wrote shortly before he died: "They will not be able to make us do it again another day.”

They were to be fateful words for when in May 1917, General Nivelle with the usual promise of ultimate victory and the demand for ever greater sacrifice launched the bloody shambles that was his offensive on the Chemin des Dames Ridge the French soldier at last cracked He had had enough. They would no longer march to the tune of human sacrifice, attack and be butchered like cattle.

It would be General Petain who would once again ride to the rescue of the French Army reorganising it and restoring morale, but he did so with the promise that they would remain on the defensive and they were to do so for much of the rest of the war.

Likewise, the German Army following the bloodletting at Verdun were not able to launch another major offensive on the Western Front until March 1918 and only then in the wake of their defeat of the Russians in the East.

The Battle of Verdun was summarised at the time in the words of the future British Prime Minister David Lloyd George: “One of the most gigantic, tenacious, grim, futile, and bloody fights ever waged -on those heights Gaul and Teuton fought out a racial feud which had existed for thousands of years. The concentrated fury of ages raged, and tore, shattered and killed in one intensive struggle that has no parallel in the history of human savagery.”

Share this post: