Victoria Hall Tragedy

Posted on 4th September 2021

The visit of travelling entertainers to a town always caused a ripple of excitement and it was no different when in June 1883, Annie and Alexander Fay arrived in Sunderland to put on a show of puppetry, ventriloquism and conjuring tricks for the local children.

The Fays were experienced and popular performers even if their shows had in the past been the source of complaints that the abundance of smoke, they used in their illusions had caused many children to be sick.

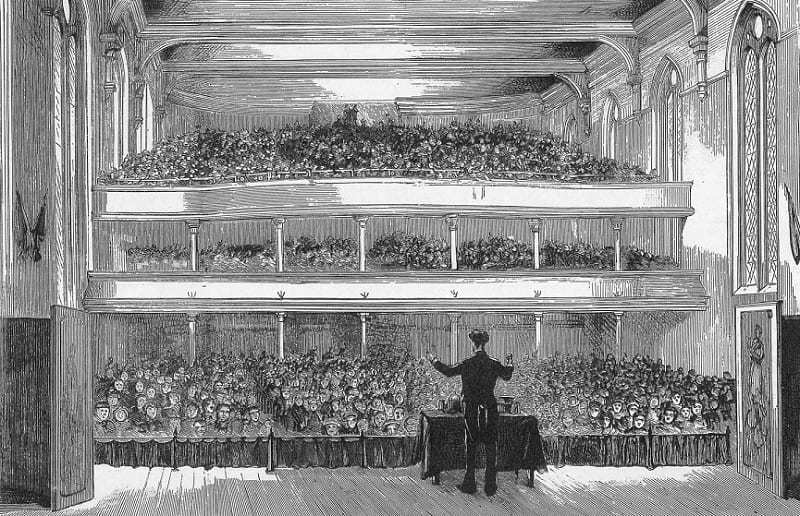

Tickets were distributed to local schools in advance of their arrival and sales were so good that by the day of the show on 16 June 1883, more than 1,200 had been sold. The Victoria Hall then was packed with excited and expectant children but the unusually large numbers meant the show was largely unsupervised while many parents taking the opportunity for a restful day allowed their younger children to be taken to the event by their older siblings.

The show had been going well and audible gasps of astonishment, cheers, applause and collective sing-a-longs could be heard emanating from the hall and the excitement only intensified as the show neared its. As the light show came to an end and the smoke began to clear from the hall an announcement was made that as the children left their tickets would be checked and if they had the right number, they would receive a gift. Mr Fay then thanked them for attendance, asked them to come again and began to distribute sweets from the stage.

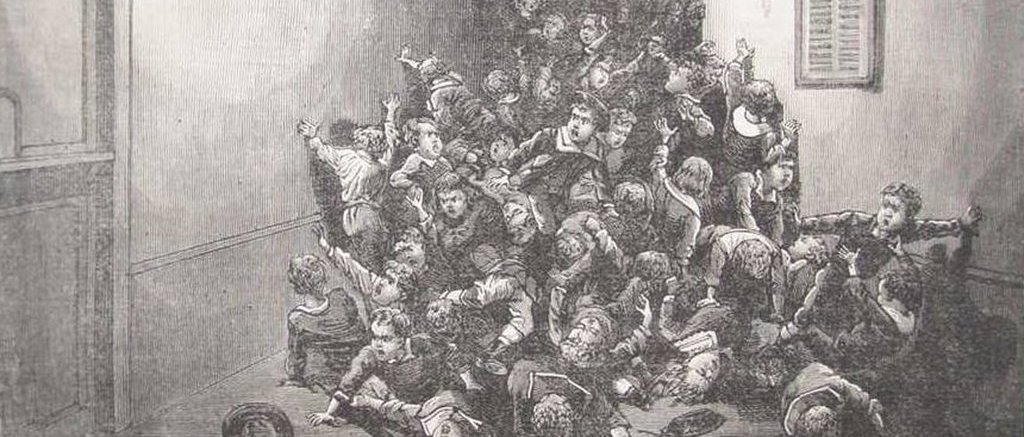

The many children in the gallery believing they would miss out rushed for the stage while other made for the stairs and crammed into the narrow hallway that led to the exit door which opened inwards onto the stairwell and had been locked slightly ajar to permit only one person to pass through at a time so their tickets could be checked as they left.

A survivor of the tragic events that followed William Codling later recalled the scene:

“Soon we were most uncomfortably packed but still going down. Suddenly I felt that I was treading upon someone lying on the stairs and I cried in horror to those behind "Keep back, keep back! There's someone down." It was no use, I passed slowly over and onwards with the mass and before long I passed over others without emotion.”.

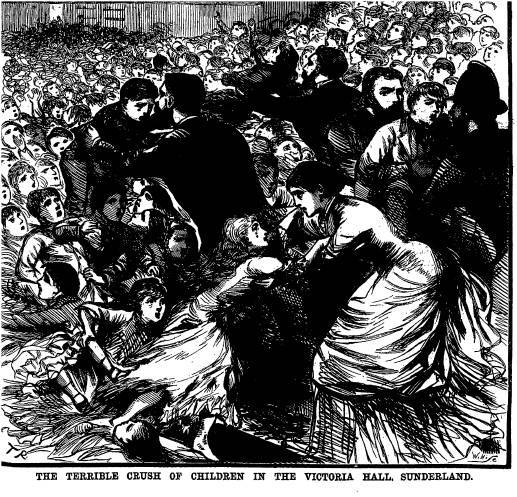

Those children who reached the door could not get through quick enough and as more and more joined the surge those at the front were pushed up tight against it. The screams of the children being crushed were at first mistaken for shrieks of excitement but as the reality of the tragedy emerging became clear some men desperately tried to push open the door, but the weight of the crush was too great.

Children who had stumbled were now trampled upon by those following behind and their cries and pleas for help were unbearable to hear but there was little anyone could do.

The caretaker of the Hall Frederick Graham unable to help those children already crushed, pinned up against the wall and trampled underfoot ran up another staircase to prevent others from coming down and managed to divert more than 600 children to safety by another exit.

Distraught parents who had arrived at the scene were pulling children through the partially opened door one at a time most already dead. By the time help arrived and the door could be removed from its hinges it was too late, and of the more than 600 children found jammed into the short narrow hallway 183 (114 boys and 69 girls) aged between 3 and 14 were found trampled, suffocated or crushed to death and it was reported that at the door itself the bodies lay twenty deep.

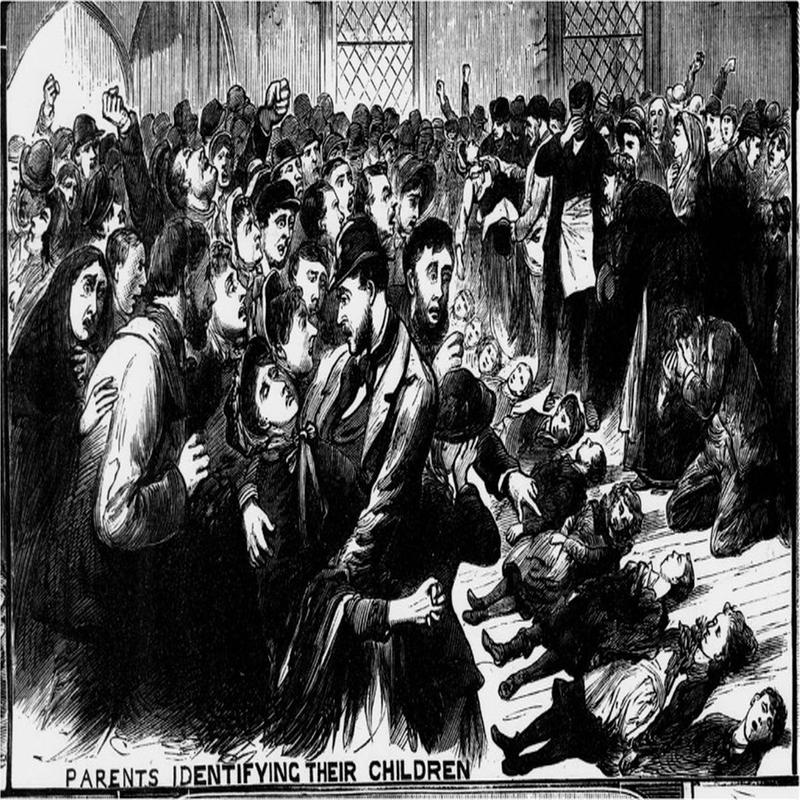

The dead children were taken to the main hall of the theatre where they were lined up in neat rows as distraught relatives rushed to it from all around to begin an identification process that saw many parents or close relatives of the deceased refusing to look upon the child instead identifying them by a scarf, a bonnet or another recognisable piece of clothing.

The tragedy was a trauma for the town which was plunged into a deep mourning and a Relief Fund was established to pay for the many funerals that took place over the following weeks.

Queen Victoria personally donated £50 to the fund and sent a letter of condolence to the families in which she quoted from the Bible (Luke 18:16): “Suffer little children to come unto me and forbid them not; such is the Kingdom of God.” Many of the parents had the letter read out at their child’s funeral.

The Court of Inquiry following the tragedy, despite the great public outrage, did not hold anyone to have been responsible but did recommend that all public venues be fitted with outward opening emergency exits that must remain unlocked while the venue was in use. This resulted in the invention of the push bar operated door.

The Victoria Hall Tragedy which remains the worst of its kind in British history was one of many that occurred during the Victorian era and a memorial to its victims now stands in Sunderland’s Mowbray Park.

Tagged as: Victorian

Share this post: