Victorian Death

Posted on 17th April 2021

The Victorians had a relationship with mortality often referred to as a ‘Death Cult’ when in truth it was not an obsession with death but the desire to preserve life after death through custom, ritual, image and the written word.

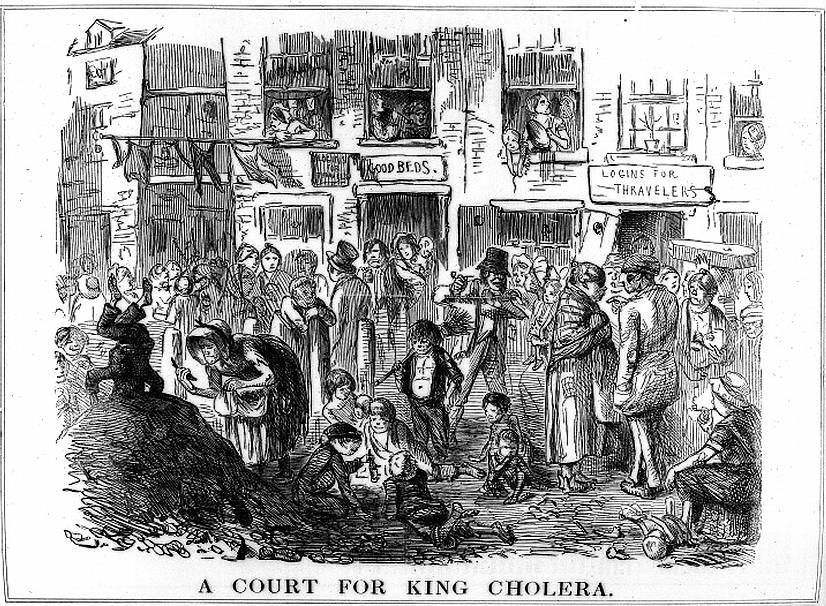

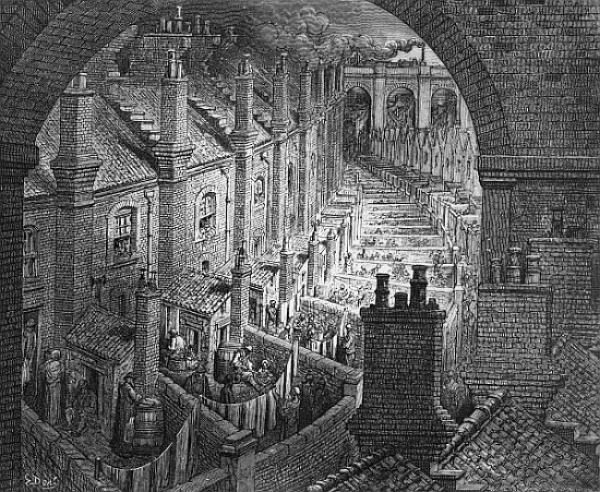

But then it was a time of disease and epidemics - of foul air, adulterated food, polluted water, overcrowded conditions and minimal sanitation. Death at a young age or in the prime of life was commonplace with infection rife the pallid complexions and skeletal figures of the sick quite literally stalked the streets of Britain’s cities.

The frequent re-occurrence of epidemics and pandemics such as cholera and typhoid fever took a great many lives but none more so than that permanent feature of Victorian life consumption or tuberculosis also known as ‘White Death.’

Wealth and privilege were no guarantee of immunity from the diseases that accounted for so many lower down the social order. In 1861, Queen Victoria’s husband Prince Albert died of typhoid fever that had almost certainly been contracted from drinking filthy water at Buckingham Palace.

The philosopher Thomas Hobbes had written in his Leviathan that life was – nasty, brutish and short. It was a phrase from an earlier time but it resonated more than ever even in a period of such great technological innovation and scientific advance for life in Victorian Britain was all those things.

In 1840, life expectancy was 29 years with 1 in 5 babies dying within a year of their birth and 1 in 3 children before they reached the age of 5. Disease could strike at any time and to devastating effect. For example, in the spring of 1856 Scarlet Fever struck the family of the Reverend A.C Tate: On 6 March, his daughter Charlotte died, on 11 March, Susan Elizabeth, on 20 March, Frances Alice, on 25 March, Catherine Alicia and on the 8 April Mary Susan.

He had lost all his daughters and five of his seven children to illness in less than three weeks and the medical profession had proved no more effective in preventing it than had the power of his prayers.

Scarlet fever was just one of the many diseases that would strike without warning reaping a grim harvest and producing in the Victorian mindset a level of fatalism that manifested itself in obsessive mourning and relentless commemoration.

Cholera, most virulent in the summer months first came to Britain in October 1831 when a ship carrying the infection docked in the port of Sunderland. It soon spread and by the time the outbreak had run its course more than 32,000 people had died. It would return with equally devastating results in 1848, 1853, and 1861.

Cholera had a frightening aspect as the blood coagulating in the veins would turn the victim’s skin blue with death occurring within a few hours of the first signs becoming visible causing panic, hence the term ‘Blue Funk.’

In 1854, the physician Dr John Snow narrowed down the source of a cholera outbreak in London to a single water pump in Broad Street. As a result of his findings the Local Council had the handle to the water pump removed. But the discovery of the cause and effect of disease did not necessarily provide the solution and once the cholera outbreak appeared to subside the handle to the pump was simply replaced.

Tuberculosis, also known as consumption, was a slow death and not always an obvious one but as contagious as the flu it was easily spread with people often going about their business despite declining health until the moment of their death. It was the greatest single killer of the Victorian era it had many notable victims almost certainly among them the Bronte sisters – Emily in 1848, aged 30; Anne in 1849, aged 29; and Charlotte in 1855, aged 38.

The sexually transmitted disease syphilis, known as the ‘Great Pox’, was responsible for as many as 50,000 deaths a year reaching its apex in the 1860’s when it was estimated than more than half of all prostitutes carried the disease and a third of troops stationed in Britain had contracted it. With its slow mortality rate numbers of the syphilitic are difficult to calculate but some experts believe it likely to have been in the millions and it has often been viewed as the ‘disease of the respectable classes.

The famous cook and mistress of household management Isabella Beeton contracted the disease from her husband on their wedding night. But in Victorian society anything relating to sex was more often the cause of moral outrage than an issue worthy of medical investigation.

Other diseases that accounted for a great many lives were smallpox, and rubella, which was particularly virulent and deadly in children. Then there was just general ill-health brought about by poor living conditions and a lack of sanitation.

Damp was a permanent feature of Victorian life and homes with wallpaper which is seen as a pre-requisite of contemporary interior design was often in fact used to hide damp patches and the paper itself could often be wet to touch. It was also difficult to sufficiently dry clothes that had been washed or made wet by rain and the constant damp was the cause of frequents chills and colds weakening the immune system.

Raw sewerage, industrial waste, and the detritus of dead animals were also regularly disposed of in the same rivers that were used for bathing, cleaning clothes and as drinking water.

It is hardly surprising given the proclivity of disease and the high number of fatalities caused by a dearth of health and safety measures either in the workplace or elsewhere that the Victorians embraced death in a way that we would now consider maudlin.

Following a death, a period of very public mourning would be expected the burden for which would invariably fall upon the women of any household and the mourning would be expected to occur at home. Often this would involve the laying out of the corpse in an open casket for family, friends and neighbours to file past and pay their last respects - doors would be kept shut, curtains replaced with black drapes that would remain drawn and the clocks stopped at the deceased’s passing.

The custom of keeping the corpse at home also had a practical purpose providing as it did time for the corpse to decay sufficiently to render it worthless to anatomists and thereby less attractive to the Resurrection men or Body-snatchers.

IIt had previously been traditional for the dead to be buried in their finest clothes and with valuables such as a silver cigarette case or gold pocket watch and as a result freshly dug graves became a magnet for the Resurrection men and so family members remaining at the graveside overnight to retrieve the valuables themselves in the morning became a familiar sight. By the time of the Victorian era however the finery had been restricted to the period of the laying out.

Women would be expected to wear only black for a suitable period of mourning which would vary, depending on the social standing of the deceased. This would not only be expected of a wife but also her daughters, and other female members of the family. Any semblance of mirth was frowned upon as also was social discourse of any kind – doleful silence was the prerequisite of the recently widowed.

The bereaved were expected to be deeply saddened by their loss but not to be emotionally overwrought, a solemn dignity was required.

The invention of the daguerreotype in 1839 provided the middle-class who had not been able to afford to commission a portrait of the recently deceased in life could now do so in death in the form of the photographic image and a booming trade now developed in what became known as ‘Memorial Portraiture.’

The dead, dressed in their best clothes were positioned in life-like poses, sometimes even standing up with their eyes forced open and often with their close relatives appearing alongside them. Particularly popular were photographs of dead children with their grieving mother’s. Death was no longer merely a communion with God but with the image maintained in perpetuity.

The Victorian era also witnessed the building of the vast park cemeteries that became such a feature of the rapidly growing industrial landscape going far beyond the confines of the traditional churchyard they provided scope for ever bolder expressions of grief and commemoration with elaborate tombs and headstones sometimes a statue of the deceased or in the case of children an angel its arms outstretched and arching to the heavens.

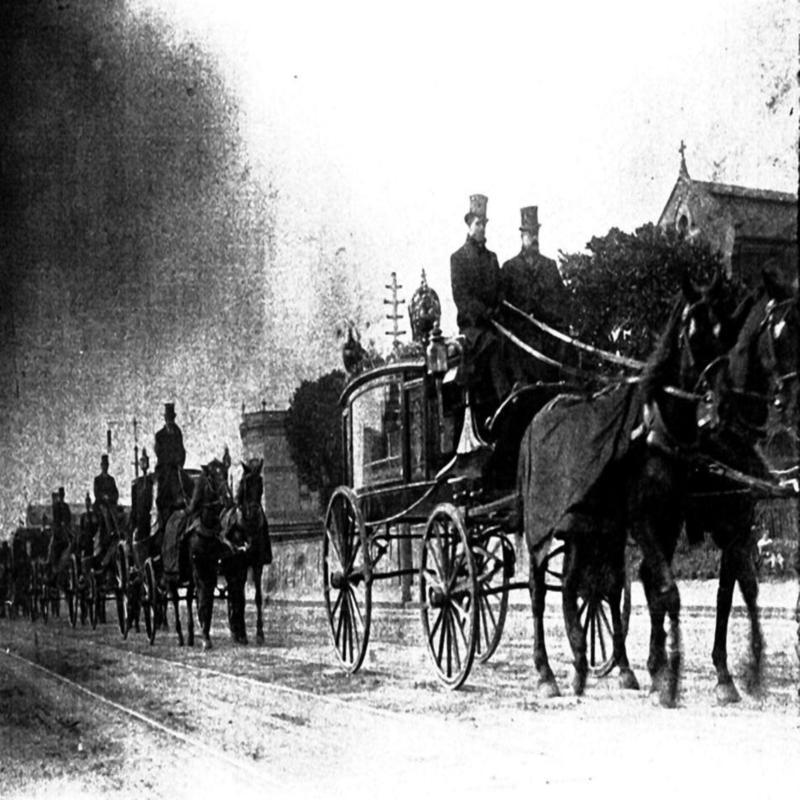

Epitaphs that had in the early decades of Victoria’s reign often been condemnatory suggesting that a premature death bore witness to a life lived in sin now became elegiac in tone. It was also the time of the extravagant funeral.

It was the family’s responsibility to provide for a Minister to speak a few words over the grave regardless of the deceased’s own wishes.

Just as bold display was so central to Victorian life so it would also be in death with even the poorest paying into a funeral club to ensure the dead received a good send off and it was not uncommon to witness a funeral procession with mourners often walking slowly to the cemetery slowly alongside a hearse pulled by dark horses adorned with black plumes in a scene of solemn grandiloquence.

As general sanitation improved and a greater understanding of germs as the cause of disease rather than the miasma theory of foul toxins in the air spread by the prevailing winds transformed the science of medicine, so the death rates began to fall and our obsession with it likewise.

Tagged as: Victorian

Share this post: