Victorian Workhouse: The Pauper's Prison

Posted on 27th November 2021

The Workhouse was intended to be the solution to an age-old problem, England’s disjointed and dysfunctional system of Outdoor Relief or the resources provided to the poor and destitute to provide for themselves and their children the burden of which fell upon ratepayers of any parish.

Charity funded Alms House and Church run homes for the poor and disabled had been around for centuries but technological innovations particularly in agriculture making it less labour intensive; and the return of some 200,000 soldiers seeking work following the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815, had increased unemployment significantly and the largely ad-hoc implementation of the Poor Law could no longer cope.

This unemployment was particularly bad in rural areas where the law of supply and demand had been determined by the introduction of agricultural machinery that greatly reduced the number of people required to work on the farms while those still employed on the land also suffered due to farmers continually reducing wages to save money.

The Old Poor Law which was administered at the local parish level was costly and the strain on it was proving unsustainable. Something had to be done to change it and it was hoped that a more centralised and regulated system would reduce the burden on the property-owning middle class upon whom the costs of supporting the poor fell.

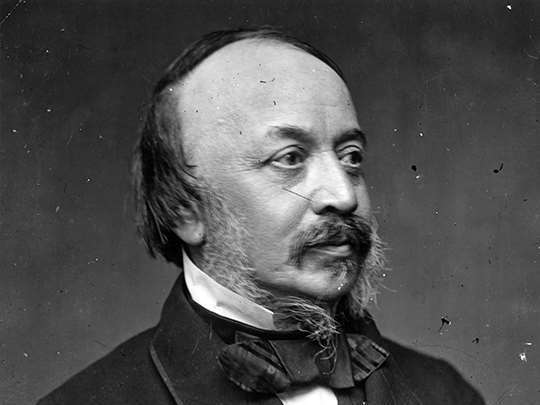

In 1832, the Prime Minister Earl Grey established the Royal Commission into the Operation of the Poor Laws It was presided over by Charles Blomfield the Bishop of London but its leading light was Edwin Chadwick the lawyer and utilitarian social reformer who influenced by the work of Reverend Thomas Malthus who believed that population would always increase faster than the resources available to sustain them worried that placing so many of the poor in close proximity to one another would only encourage them to indulge their baser instincts.

Even so the Poor Law Commissioners concluded that the current system of Outdoor Relief was ruinously expensive and breeding a nation of the lazy and the indolent who were work shy and not interested in seeking employment. It was corrupting the poor it was intended to help, and needed a serious overhaul.

As an Assistant Commissioner, Edwin Chadwick was employed to travel the country and collect of information and data. He proved very good at his job and when the final report was published it was, he who was largely responsible for it.

The Poor Law Report was published in February 1833. It recommended that all Outdoor Relief should cease, and that Workhouses be built in every parish or in a union of parishes in England and Wales. Only in the Workhouse would relief be provided and upon terms that only the most indigent and desperate would accept. The Workhouse itself would be overseen by a Board of Guardians made up of prominent local ratepayers and run by those they employed.

Many of the recommendations made by Chadwick particularly those regarding the moral improvement of the inmates were either rejected by the Commission or never fully implemented and he was to express his disappointment of what he considered a watered-down report.

The Act for the Amendment and Better Administration of the Laws Relating to the Poor in England became law on 14 August 1834.

The new law was designed to force the hand of the poor, either find work or enter the Workhouse. There was no other alternative, if you turned to crime, you would either go to prison or end up on the gallows, if you remained on the streets, you would starve and die.

Only the neediest of the people should enter the Workhouse and as such they were to be brutal, harsh and unwelcoming to deter others from doing so unless absolutely necessary. For example, a married man unable to find work would if he entered the Workhouse have to bring his entire family with him even if other arrangements had been made for them, a last resort just as the government intended.

People entered the Workhouse for different reasons however, many because they could not find work it was true, but others were disabled or simply too ill to take care of themselves. Likewise, orphaned children would be placed in Workhouses often for their own safety. So, the Workhouses took all - the old and infirm, the disabled and the sick, the unmarried and their bastard offspring.

There were 1,800 Workhouses built housing at any one time around 90,000 inmates but this would swell at times of economic hardship. They also varied greatly in size some would house as little as 50 inmates’ others could house several thousand.

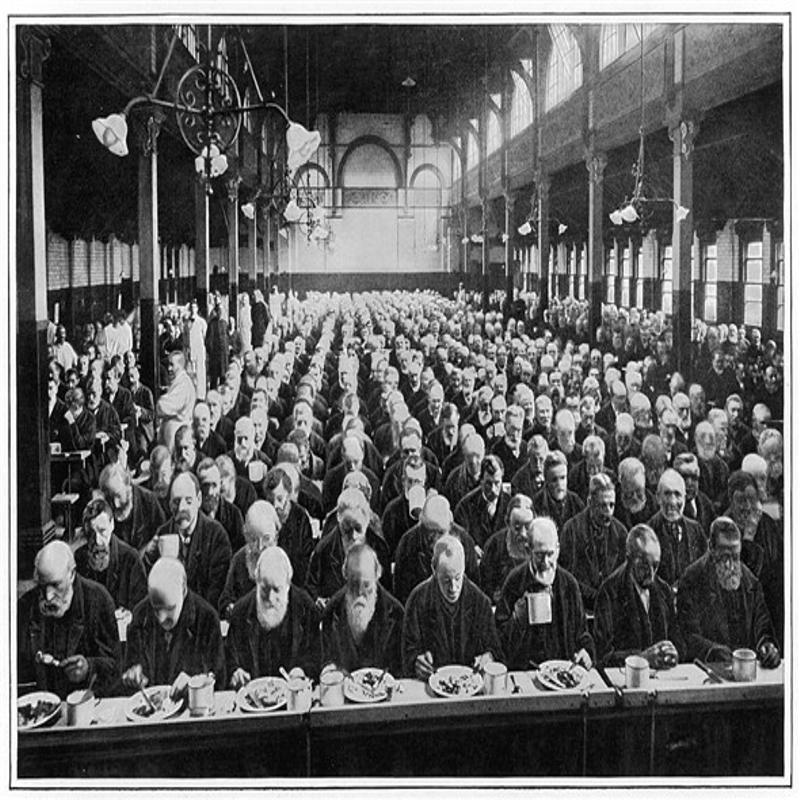

The buildings themselves were often of a forbidding central structure surrounded by exercise yards, outdoor work areas and sometimes a wall. They were also designed in a way that would facilitate the segregation of the men from the women and mothers from their children with separate dining rooms, separate communal areas, and separate outside spaces.

When entering the workhouse for the first time the inmates would be stripped, bathed and have their clothes and personal possessions taken from them before being issued with a standard uniform and boots. These could vary from Workhouse to Workhouse.

These uniforms could vary slightly for each workhouse but would mainly consist of, men a striped jacket and trousers with cap and women a striped dress and smock with cap. In some workhouses there would also be different uniforms for pregnant women and prostitutes intended to single them for the appropriate opprobrium.

Young children under the age of seven could be housed with their mother and it was intended that mothers should be given ‘reasonable access to their children but this was done at the discretion of those running the Workhouse.

The inmates were placed in different groups: able bodied men sixteen years and above; able bodied women sixteen years and above; men - the ill and the infirm; women - the ill and the infirm; boys aged between seven and fifteen; girls aged between seven and fifteen.

These groups were fully segregated and were not allowed to interact with each other at any time. Any caught doing so whether it was talking or even signalling to one another would result in punishment. This could be solitary confinement, deprivation of food, and in extreme cases such as repeat offending or physical/sexual conduct even flogging.

There were also many petty rules and obligations that banned activities such as whistling and singing with signs placed throughout the Workhouse reminding the inmates of the punishments that might accrue for any infraction of the rules. For those who were illiterate the rules would be read out at the beginning of every week and repeated at regular intervals thereafter so there could be no excuse for disobedience.

Living conditions were also harsh with inmates cramped into dormitories where they sometimes had to share a bed and had no individual personal space of their own. The beds would be plain wooden and iron with a flock filled sack used as a mattress, thin blankets and no pillow as this was considered unnecessary and superfluous. Inmates were also not permitted luxuries such as tobacco, newspapers or books while children were not allowed toys or games, not that there was much time for rest, relaxation or play. These restrictions were eased somewhat in 1860 when books and magazines received as the result of a charitable donation and deemed suitable were made available.

The Workhouse regime was regulated and ran to a very strict timetable, a typical example of which was:

5 – 6 am Rise

6 – 7 am Prayers and Breakfast

7 – 12 pm Work

12 – 1 pm Dinner

1 – 6 pm Work

6 – 7 pm Prayers

7 – 8 pm Supper

8 - 9 pm Bed

Inmates were also expected to work; men’s jobs included breaking stones, bone crushing, picking oakum, wood chopping and corn grinding. Women’s jobs were mostly domestic and included cooking, cleaning and laundry, sewing, weaving and gardening. Any income earned went directly to the Workhouse.

Children, who by 1839 would already number more than half of Workhouse inmates, were also provided with jobs and were sometimes hired out to local mines and factories. They also spent much of their time at school with the Board of Guardians hiring teachers the quality of whom would improve over time.

For those orphaned children the Board of Guardians would serve as surrogate parents until they became old enough to enter permanent employment usually 14 to 16 years of age. Some Poor Law Unions did seek to transport children to be raised in the colonies, but this was frowned upon by charitable organisations. Workhouse boys would often go on to serve in the army or navy while the girls schooled in household chores would become a valuable resource for domestic service.

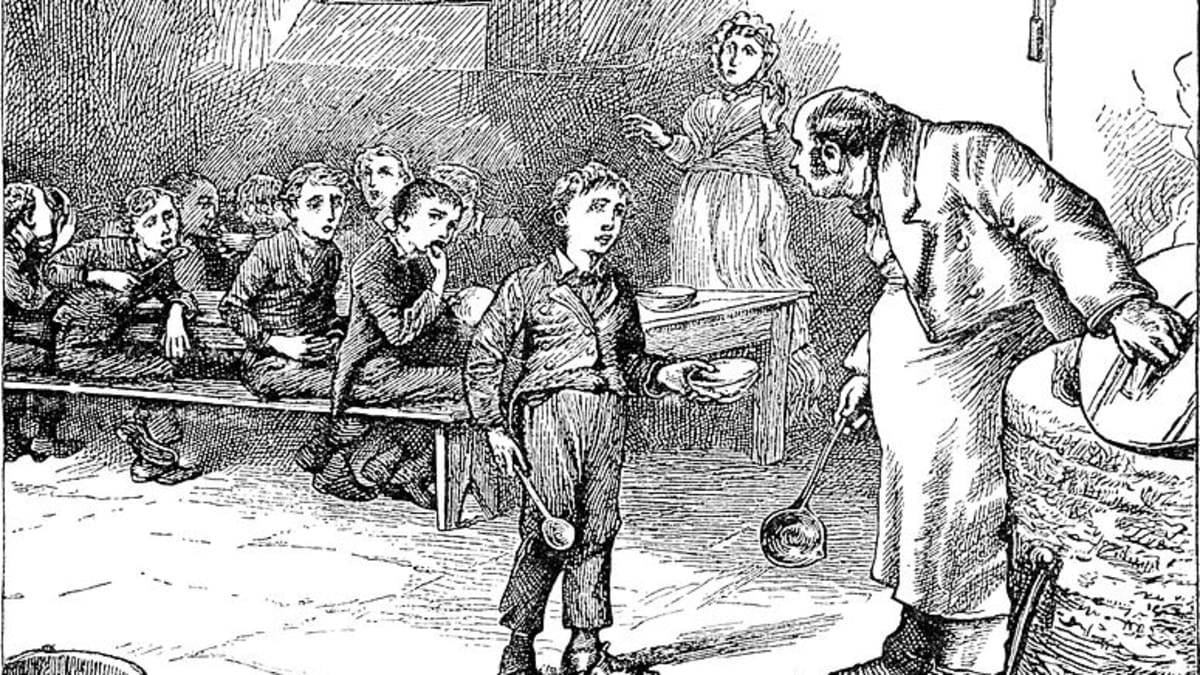

The food in Workhouse’s was not intended to be to be either ample or palatable. Local variations might apply but a typical menu would be: Bread, cheese, potatoes, vegetables, and gruel (a thin soup made of wheat, oat, or rye flour and rice boiled in milk or water). Meat was rare. The food provided was normally grown in the vegetable garden and both prepared and cooked in their own kitchens. A Workhouse also had its own laundry, infirmary, chapel and mortuary. Some even had their own cemetery.

Disease was rife within the cramped dormitories and illness such as dysentery and smallpox were commonplace. Although the sick received care they were not separated from the already old and infirm ensuring those in the mortuary and the gravediggers were kept busy.

As entry into the Workhouse was voluntary inmates could leave if they wished and as such for most it was a short-term stay. A Parliamentary Report of 1861 showed that only 20% remained more than 5 years.

There were many workhouse scandals and frequent reports of mistreatment. One of these was the Andover Workhouse Scandal of 1845 – 1846.

Around the Andover area rumours had been circulating for some time of maltreatment in the Workhouse. The inmates it was said were being deprived of the most basic of amenities in particular food, that the men employed in the work of Bone Crushing were so hungry that they were fighting each other to strip the marrow from the rotting bones.

The Board of Guardians accepted an urgent request from outside agencies to visit and check for themselves if the rumours were true. When they found then to be just the tip of the iceberg a Public Inquiry followed.

One thing that emerged from the Public Inquiry was that the Andover Workhouse had not been inspected for six years even though the Poor Law stated that Workhouses were to be inspected annually. It also found that many Workhouses were being run for profit and the inmates a resource to be exploited.

Much of our understanding of the Workhouse comes from Charles Dickens who wrote about it extensively in Oliver Twist published 1838. His depiction of it is perhaps exaggerated but not entirely inaccurate and they early on became known derisively as Bastilles.

The two most famous inmates of the Workhouse were perhaps John Rowlands, the future Henry Morton Stanley who discovered Dr Livingstone who entered the St Asaph Workhouse in Flintshire aged of 5 and remained 9 years taking full advantage of the educational opportunities on offer while he was there; and Charlie Chaplin who with his mother and brother went into the Newington Workhouse in 1896.

Regardless of their unpopularity and the many scandals surrounding them the Workhouse system of poor relief was to remain in force for almost a hundred years. It wasn’t until the various Social Security Acts introduced by the Liberal Chancellor David Lloyd George in 1906 including unemployment benefit and first old age pension that the requirement for a parish Workhouse diminished and by 1928, they had effectively ceased to exist.

Tagged as: Victorian

Share this post: