Wartime Rationing

Posted on 27th July 2021

When war was declared in September 1939, Britain was far from self-sufficient importing 50 million tons of foodstuffs a year, or 70% of its total requirement including 50% of its meat, 70% of its cheese, cereals and fats, 80% of its fruit, and almost all its sugar – by 1942 this would drop to just 12 million tons.

In February 1917 at the height of the Great War Germany implemented a policy of unrestricted submarine warfare that was to see Britain come within weeks of starvation. It had only been the adoption of the convoy system protected by armed escorts that had prevented it from being so.

Similar would have to be implemented again and the fact Britain possessed the largest Merchant Marine in the world would mean the Royal Navy’s resources would be stretched to the limit.

For the most part food stocks had remained high during the Great War and limited rationing wasn’t imposed until February 1918, but the sudden collapse in the number of imported edibles due to increased U- Boat activity revealed in the starkest terms Britain’s vulnerability to having its vital maritime artery severed during a time of war and of slowly bleeding to death as a result. It had worried the Government then – it worried them still.

Indeed, with so much of the country’s Merchant Fleet given over to the transportation of arms and other essential war materiel Prime Minister Winston Churchill would say that it was only the Battle of the Atlantic that kept him awake at night.

With priority given to the armies in the field the British people would have to feed itself and the country be galvanised into a supreme effort to do so.

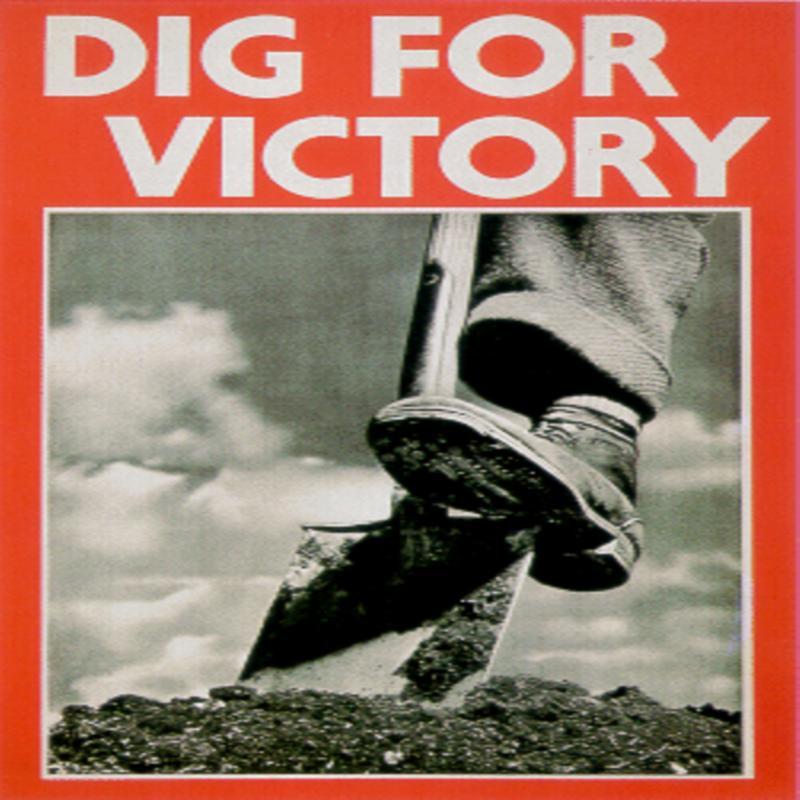

The Ministry of Agriculture had begun its ‘Dig for Victory’ campaign even before rationing was introduced; posters adorned all public buildings, millions of leaflets were delivered with the morning mail and adverts preceded the main feature at every cinema encouraging people to turn their gardens into cabbage patches, to cultivate wasteland and to increase the size of their allotments.

As early as September 1939, the first ‘Grow More Bulletin’ was issued advising gardeners how to change from flowers to vegetables with regular updates to follow.

In October, the people were told in a radio broadcast that 500,000 more allotments would produce enough potatoes and vegetables to feed 2.5 million adults and children for eight months. People were also encouraged to keep their own chickens and goats, to rear their own rabbits and the better-off could even purchase their own pigs.

Soon public parks and football pitches turned into ploughed fields became a common sight, even small pockets of inner-city land such as that available outside St Paul’s Cathedral was cultivated as were the lawns that surrounded the Tower of London – every patch of land where food could be grown would be given over to its production.

By the end of the war the number of allotments had increased almost two-fold from 800,000 to 1.4 million and were producing more than 10% of Britain’s total foodstuffs.

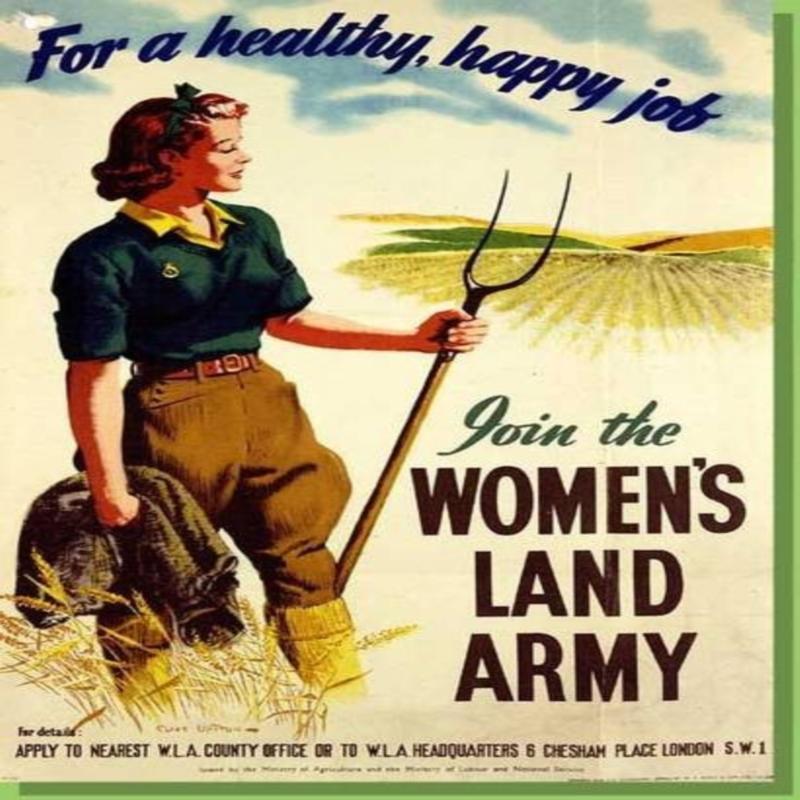

The Women’s Land Army had already been reformed in July 1939, as war loomed to replace agricultural workers who would be needed for the Armed Forces and some 80,000 ‘Land Girls’, many of them volunteers would keep the farms going, ploughing the land, sowing the crops and gathering in the harvest.

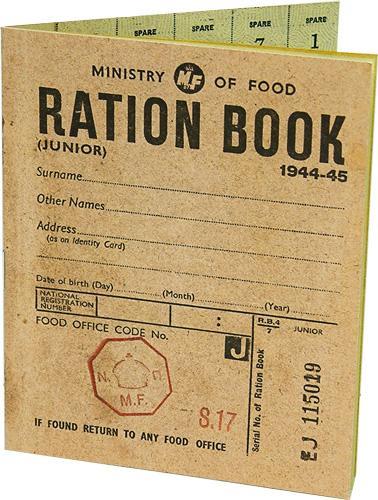

With special measures having already undertaken to prevent the mass-hoarding of food which had occurred during the early months of the Great War on 8 January 1940, rationing was introduced in Britain and the wasting of food made a criminal offence.

Food stock preservation and distribution was to be run by the Ministry of Food under Lord Woolton who was to become one of the most familiar faces of Britain’s war effort.

Every adult and child were to be issued with a ration book and had to register with a single shop for the items of food they required and as there were no supermarkets this meant signing-up with an individual butchers and grocers etc.

As ration books were non-transferable what meat, cheese and vegetables could be purchased or received were always subject to availability. What a person could receive would reflect that individual’s circumstances but a typical adult weekly ration would be:

1/ Bacon and Ham 4oz (100 g)

2/ Meat to the value of 1s 2d – the fact that meat was rationed according to its monetary value meant that cheaper cuts such as corned beef and offal like liver, tripe and kidneys became extremely popular though this too had been rationed by 1942. Sausages were not rationed mainly because butchers rarely receive the meat to produce them.

3/ Cheese 2oz (50 g) but could rise to 8oz (225 g) depending on availability.

4/ Butter 2 oz (50 g)

5/ Margarine 4 oz (100 g)

6/ Milk 3 pints (1800 ml) occasionally reduced to 2 pints with 1 packet of dried milk per month.

7/ Sugar 8 oz (225 g)

8/ Jam 1 Ib (450 g) every 2 months

9/ Tea 2 oz (50 g)

10/ Eggs 1 per week (but often only every 2 weeks)

11/ 1 packet of dried eggs per month.

12/ Sweets 12 oz (350 g) per month.

The health of children was given special consideration in the compiling of ration books and schoolchildren would be given a weekly dose of Virol, a sticky malt-based extract to ensure they would not become vitamin deficient.

Not all foodstuffs were rationed, and it was possible to still purchase vegetables in the normal way but they were often in such short supply that shopkeepers would impose their own restrictions. For example, apples and onions could be bought but often only at one per person per day.

People found it difficult to adjust at first and it wasn’t uncommon to try and erase the mark or stamp that had been made in the ration book and reuse the coupon.

It became then a time of great creativity in the kitchen and the chef Marguerite Patten’s Cooking Tips broadcast daily on the BBC Home Service regularly attracted six million listeners with the humble carrot becoming the hero vegetable of wartime Britain used in salads, casseroles, pies, cakes, and even as lollipops.

The white loaf which had become a staple diet of the British ceased to be produced during the war and was replaced in the autumn of 1942 by the ‘National Loaf’ made from a bitty and heavy wholemeal that was no doubt healthy but thought unappetising and was deeply unpopular.

Meat remained available in restaurants but with much of it purchased on the Black Market would be charged accordingly which meant that the rich could continue to dine lavishly whilst others had to make do causing such resentment that in 1942 the Government imposed a maximum price on meals served in restaurants of 5/.

Earlier in 1940, communal canteens known as British Restaurants had been established to ensure that workers could receive the sustenance required to maintain their energy levels. Set up in churches and schools and run by Local Authorities on a not-for-profit basis meals were priced at 9d and despite the often-barren fare with substitute food such as whale meat and snoek fish cake on the menu the British Restaurants remained popular serving up to 600,000 meals a day and were not finally abolished until 1947.

Food is the most famous example of wartime rationing but it touched every aspect of British consumer and commercial life –soap, coal, cigarettes, wood for furniture and clothing among many others. Petrol had been denied to those not in business or working directly for the war effort since September 1939.

Scarcity of goods in any circumstances invariably creates in its wake a flourishing Black Market and this was no different during the war when ration books were regularly bought and sold (particularly those of people who had recently passed away) along with ones stolen from depots and distribution centres. Everyone knew their local Spiv, as he was known, and though they were widely despised they were rarely short of customers.

In rural areas the cases of illegal fishing and poaching increased considerably whilst in the towns and cities not only did the pigeon population decrease but so did that of cats and dogs.

But rationing also brought people together in a way that mere propaganda never could as women, it was invariably women, whether dressed in furs or dungarees could be seen in the same queues ration books in hand. It was a shared experience not dissimilar to the Blitz minus the element of danger, though few were so naive as to believe that what was required could not be bought by those who could afford it.

People could not understand why rationing continued for so many years after the wartime emergency had passed and, in many cases, became even more severe with the bacon, lard and soap ration being reduced, the sweet ration resumed, and potatoes and bread rationed for the first time.

People were sick and tired of queuing for everything but the Labour Government surviving as it was on a loan from the United States, burdened with a massive rebuilding programme, the creation of the National Health Service and the Welfare State and responsible for those areas of Europe under its occupation simply could not afford to import the foodstuffs required to bring it to an end.

In 1951, the Labour Party campaigned in the General Election on a programme of continuing rationing indefinitely. They won but with such a reduced majority that another Election soon followed which they subsequently lost despite polling more votes.

On 4 July 1954, nine years after the end of the war, the Conservative Government formally ended rationing.

Despite the deprivations of wartime Britain, the people had never been healthier. The rations that had been worked out in Cambridge prior to the war were not just based on the likely scarcity of certain foods but the requirement for a balanced diet and so just as calorie intake decreased so did the consumption of protein and carbohydrates increase.

Tagged as: Modern

Share this post: