Wilberforce and Slavery

Posted on 4th September 2021

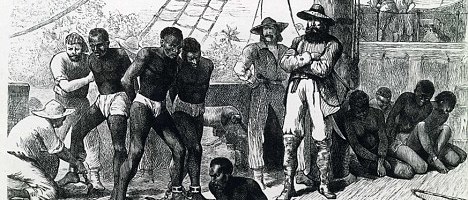

On 29 November 1781, becalmed in mid-Atlantic and fearing the spread of disease from overcrowding, Captain Luke Collingwood of the Slave Ship Zong ordered 132 sick black slaves be thrown overboard.

It was a harsh decision, but he thought a necessary one given that the cost of any slaves landed dead or near death from natural causes would be borne by the ship’s owners and crew. If they were to be disposed of at sea however, then the financial liability became the responsibility of the ship’s insurers.

Having resolved the problem Collingwood sailed the Zong on to successfully deliver the remainder of its cargo to the slave auctions of the Caribbean before returning to London where the insurance claim was duly made.

Collingwood stated that he had no choice but to dispose of the sick slaves aboard the Zong because of water depreciation but an inventory taken of the ship upon landing found that there were many hundreds of barrels of water aboard, more than enough for the journey.

The ship’s insurers decided to contest the claim.

It had not proved possible to keep the shocking events aboard the Zong a secret and they were soon brought to the attention of the anti-slavery campaigner Granville Sharp, who in the absence of Collingwood who had since passed away, tried to bring a private prosecution against the ship’s owners for murder. It was not the first time Sharp had become involved in an anti-slavery court case.

Ten years earlier he had helped achieve a landmark ruling when a reluctant Attorney-General Lord Mansfield, after considerable prevarication, had to concede that an American slave James Somersett who had been captured and imprisoned by his master to await transportation back to America after 56 days on the run in London was being illegally held and should be released on the grounds that - slavery did not exist in England.

As was pointed out at the time the ruling applied only to the specific case under review and not generally, but it was significant nonetheless and was to provide the reference point of precedence in all such future cases - and it was a personal triumph for Sharp.

He was to be less successful this time however, with the recently appointed Attorney-General Sir John Lee dismissing the case out of hand: “What is this claim that human people were thrown overboard. This is a case of chattels and goods. Blacks are goods and properties. It is madness to accuse well-serving and honourable people of murder. The case is the same as if wood had been thrown overboard.”

When the case eventually came to Court in March 1783 it would not be for mass-murder as Sharpe had hoped but for insurance fraud.

The attempt by Granville Sharp, who in previous decades had appeared almost as the lone voice of the anti-slavery movement, to bring a criminal prosecution against the ship’s owners though unsuccessful did generate a great deal of publicity for the cause. The brutal murder by drowning of sick men, women, and children aboard the Zong caused shock and outrage and provided momentum to a campaign that had in recent times appeared almost moribund.

Whilst the morality of the slave trade could be questioned its commercial viability and profitability could not, and many of the fastest growing and most prosperous cities in England had generated their wealth from the traffic in human lives.

The first slave ship had sailed from Bristol for the African Continent in 1697, one of 2,108 that were to do so before 1807 carrying around 300,000 black men, women, and children into captivity on the sugar and cotton plantations of the Caribbean and Americas, making Bristol for a short time at least the wealthiest city outside of London.

By 1740 however, its pre-eminence in human trafficking had been surpassed by Liverpool which though coming late to the slave trade had a greater capacity which saw it expand rapidly. In 1792, for example, 131 slave ships sailed from Liverpool, 42 from Bristol, and 22 from London and by 1795, Liverpool controlled 80% of the British and 40% of the European slave trade.

Despite this it never represented more than 10% of Liverpool’s overall trade and so did not, unlike in Bristol, contribute significantly to the city’s greater prosperity though it made its merchants of human misery and death very rich.

Many smaller ports also prospered from the slave trade as did the many businesses that provided it with goods and services such as merchants, insurance brokers, its many investors, the banks, and any campaign to restrict or abolish slavery would have to overcome a powerful vested interest that had become sewn into the very fabric of British commercial life.

The campaign against the slave trade led for the most part, though not exclusively, by the non-conformist religions such as the Quakers and the Methodists was rarely absent of passion and commitment but often lacked coherence, any sense of strategy, and more importantly influence.

John Wesley, one of the co-founders of Methodism had long campaigned against the iniquities of slavery but though his voice was often heard it was rarely listened to.

In 1788, an old man and in ill-health he travelled to Bristol to preach against slavery for one last time and though his body was weak his ardour remained as he made a passionate plea for justice and humanity:

“Give liberty to whom liberty is due, that is, to every child of man, to every partaker of human nature. Let none serve you, but by his own act and deed, by his own voluntary action. Away with all whips, all chains, all compulsion. Be gentle to all men; and see that you invariably do with every one as you would he should do unto you.”

His message was not always well-received and the windows of the Chapel were installed in its roof to prevent missiles, and the pulpit raised high and blocked off from the congregation to protect its speaker.

The outrage caused by the murders on the Zong had provided the anti-slavery

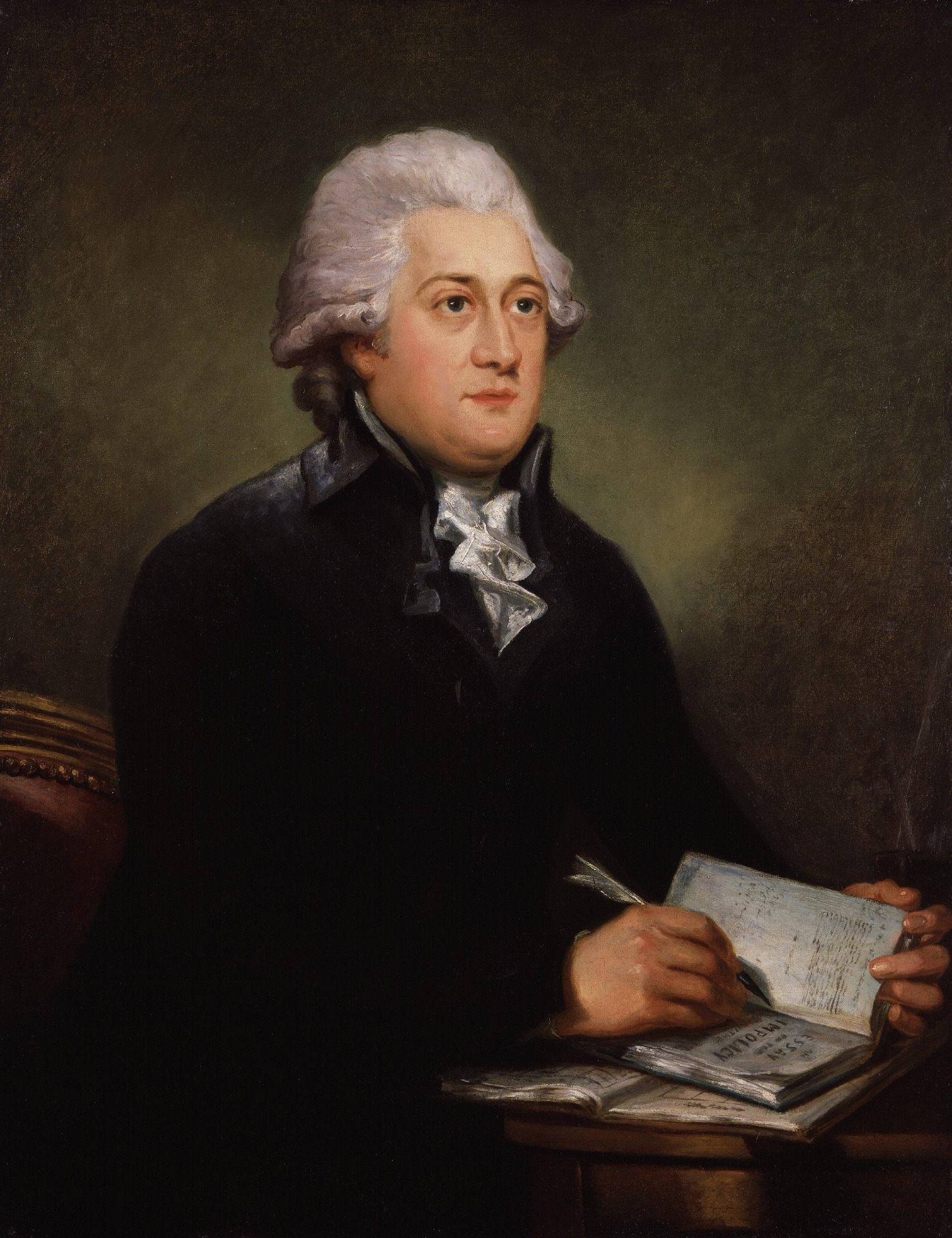

campaign with a renewed vigour but its driving force was not to be the somewhat, cloistered, and other-worldly Granville Sharp but Thomas Clarkson, the son of an Anglican clergyman who had become committed to the abolition of slavery when at university in 1785 he researched what would become a prize-winning essay on the subject. He would later write that completing the essay had been like a revelation from God: “A thought came into my mind, that if the contents of the essay be true it was time for some person to bring their calamities to an end.”

He would dedicate the rest of his life to ending not just of the trade in slaves but slavery itself.

It was his essay that was to bring him to the attention of Sharp and others, and it would transpire that the anti-slavery movement would need Thomas Clarkson as dedicating himself to the cause he toured the country visiting all the major ports, interviewing the sailors who worked aboard the ships, and purchasing the tools of the trade – the shackles, the manacles, the instruments of punishment.

He addressed audiences in the very places where he was least welcome, in the taverns overlooking the harbours from where the ships were moored waiting to embark for Africa, and the meeting houses where the deals were struck, and money counted. Often to great hostility he would remove from his bag and hold up for all to see the chains of human bondage and he wasn’t afraid to remind them from where came the money for their refined ornamentation, their delicate silks, their fine wines, and their gracious living.

Attempts were to be made on his life but the very fact that people were willing to kill for the right to enslave others was proof of slavery’s corrosion of the human spirit. It only served to embolden him further.

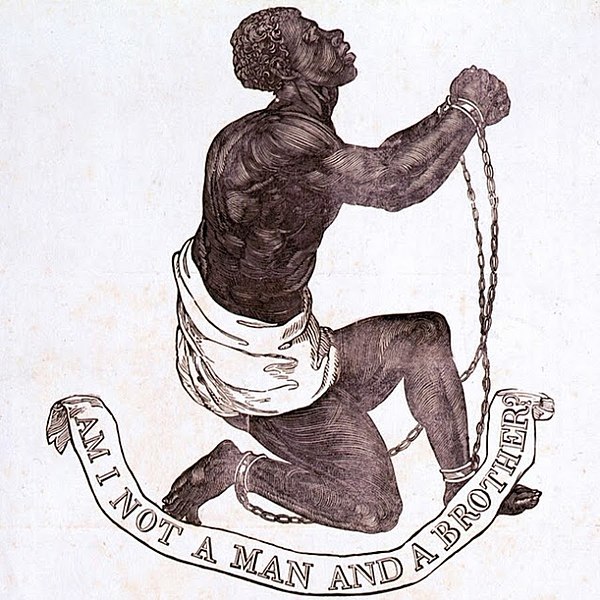

In May 1787, the ‘Committee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade’ was formed with Clarkson, Granville Sharp, the businessman Josiah Wedgwood, and the playwright Hannah More among its more prominent members.

That same year Wedgwood who had made his money in ceramics produced his famous medallion with the image of a slave and the words – Am I not a man and a brother. It would become the motto for the campaign.

As the title of the Committee indicates they were not campaigning to abolish slavery as such. This, they believed, was beyond their means entailing as it would the deprivation of property, claims for compensation, and involve them in years of endless litigation. And that was if they were successful, which they doubted they would be.

The detrimental economic impact of slavery’s abolition guaranteed it would be fought tooth and nail by the plantation owners of the Indies who were so so reliant upon black labour and their financial backers. Better to end the trade in slaves, to cut off its lifeline, and let it die a natural death. Not all agreed but it was at least a first step.

The formation of the Committee provided the anti-slavery movement with the cohesion it had previously lacked but they still remained outside the decision-making process. They required a representative in Parliament, someone of influence who could carry the campaign into the corridors of power – but who?

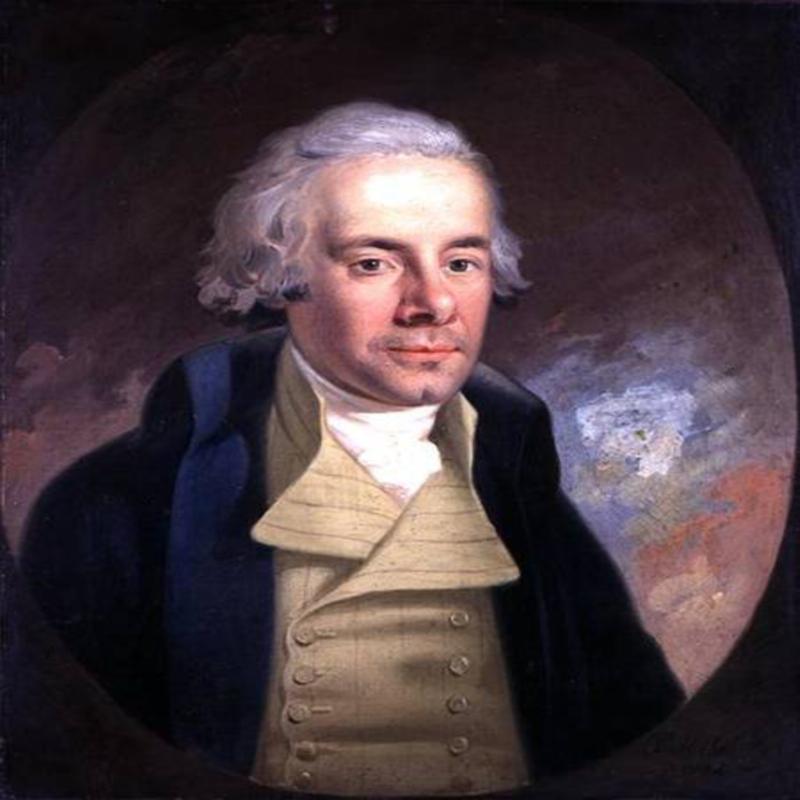

William Wilberforce was born in Hull on 24 August 1759, the only son of a wealthy merchant who unlike so many others in the city made his money trading goods not people.

When he was aged just 9, his father died and his mother struggling to cope with the loss of her husband sent the young William to live with his relatives in London. There he remained for three years before his mother concerned that he might be imbibing his uncle’s non-conformist religious views brought him back to Hull. It made little difference for he was to prove non-conformist by nature and not just education.

In 1783, Wilberforce attended St John’s College, Cambridge where he was a contemporary of the future Prime Minister William Pitt at nearby Pembroke who would become one of his closest friends.

Pitt was to prove a constant source of encouragement to his friend throughout his campaign to abolish the slave trade particularly during those dark moments of despair of which there were many; but either unwilling or unable to do so he did little to facilitate its progress through Parliament during his tenure as Prime Minister much to Wilberforce’s frustration and disappointment.

Sociable and independently wealthy as a result of several inheritances the young Wilberforce embraced the good life drinking, gambling, attending the theatre and despite being physically unimpressive with the pallor of ill-health that made him appear sick even when he wasn’t, his undoubted charm and erudition saw him favourably considered. He was then, far removed from the rather stern and puritanical figure we recognise today.

But he was also a young man who had a very high opinion of himself and believed he was destined for great things – he just didn’t know what.

Aged just 21 he became the Member of Parliament for his home town of Kingston-Upon-Hull with the intention of making his mark and doing good but the frustrations of parliamentary politics soon bore down upon him when he found that the private members bills he presented for among other things, the moral improvement of the people, were either rejected at their second reading in the House of Commons or were dismissed out of hand once they were introduced in the House of Lords.

Despite these early failures he remained an independent refusing to join either of the two factions within Parliament - the Tories and the Whigs.

Disappointed he took solace in what he always had the card tables and bawdier entertainments of Georgian London. In October 1784, he embarked upon a Grand Tour of Europe, a rite of passage for any young man or woman of means returning a year later having it seems undergone a religious conversion. He now doubted whether the combative arena of politics was a suitable place for a man of God and considered resigning as an MP on the grounds of conscience.

He was dissuaded from doing so by his friend Pitt and John Newton, the ex-slave trader turned clergyman who was the author of the hymn Amazing Grace; he could do more good inside Parliament than he ever could from without, they told him. So he would serve God but not in the cloistered world of solitude, prayer, and quiet devotion but in the sphere of public life.

Wilberforce’s reputation as an independent, his conversion to Christian Evangelism and his subsequent joining of the Clapham Sect, a group of Christian social reformers and activists, soon came to the attention of those campaigning to end the moral outrage that was the slave trade. It was suggested by Charles Middleton, a Naval Captain who was himself an MP but one of poor debating skills that the independent-minded William Wilberforce might be persuaded to take up the anti-slavery cause in Parliament.

It was agreed that Thomas Clarkson should contact Wilberforce which he did at his home in Old Palace Yard within sight of the House of Commons armed with his Essay and his familiar box of chains and manacles. Clarkson explained in detail the appalling conditions aboard the slave ships and the harsh treatment meted out to the slaves themselves.

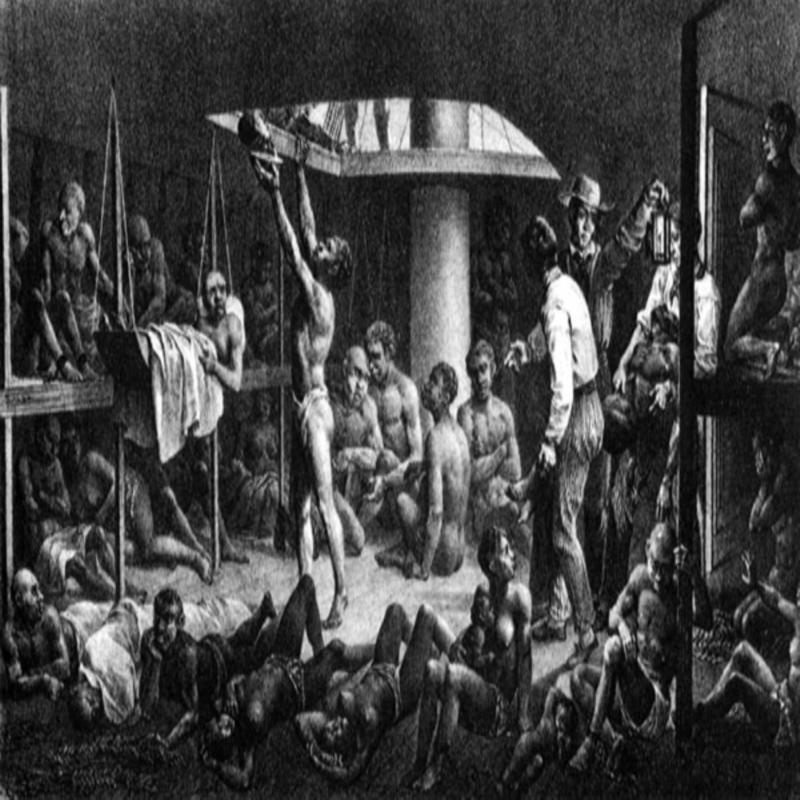

Sailing at full capacity the men taken below would be chained to their bunks, unable to stand up or move about and forced to urinate and defecate where they lay - the air was putrid, the smell foul and disease quickly spread making illness commonplace.

The women and children would be quartered on deck where exposed to the elements the conditions were hardly any better and at night were vulnerable to sexual molestation and rape.

Often slaves would be forced to perform for the crew’s entertainment, dancing or singing. If they refused or in any other way misbehaved, they would be punished and more often than not made to bow in gratitude for having been so.

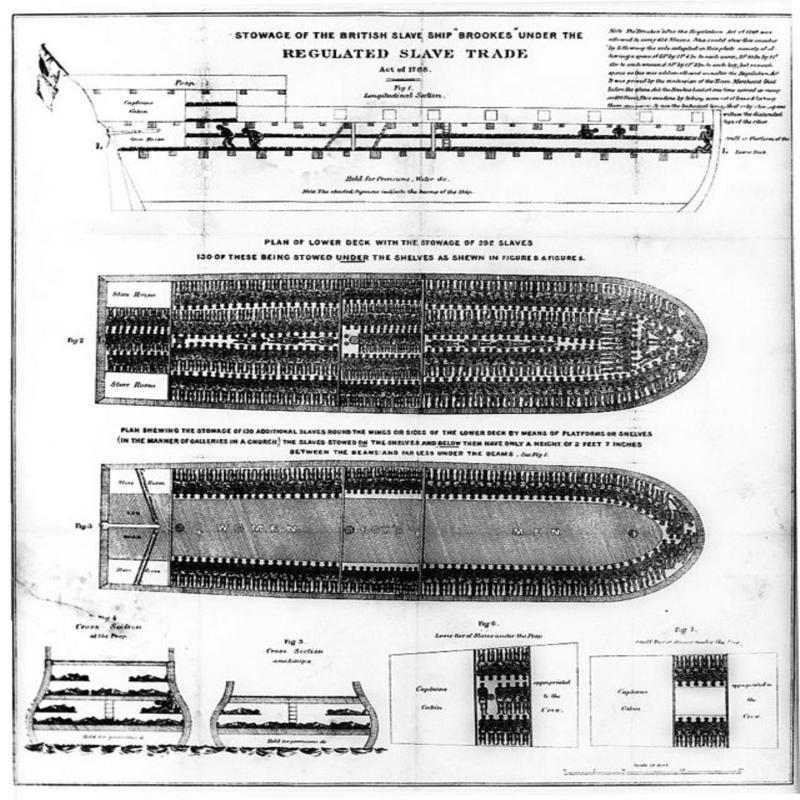

So awful was the journey from Africa to the Americas, the so-called Middle Passage, that it has been estimated that tens of thousands of slaves died before ever reaching their destination. To illustrate the deprivations endured by these ‘poor unfortunate wretches’ Clarkson would later produce his famous lay-out of the Slave Ship Brookes:

Little of this was unknown to Wilberforce who’d had such discussions before but Clarkson with his power of persuasion and the facts to hand could convey the reality better than most. The two men spoke for some time but Clarkson made no proposal other than to suggest they should meet again.

On 13 March 1787, Wilberforce was invited to attend a dinner party at the home of Bennet Langton a committed abolitionist along with other guests such as the artist Sir Joshua Reynolds, James Boswell the biographer of Samuel Johnson, and a number of fellow MP’s.

The conversation though it ranged over many things kept coming back to the theme of injustice – how could there ever be social reform or an improved morality when the original sin of slavery stalked the streets of every city and town in Britain, when its profits constructed their municipal buildings, when the blood of slaves signed the documents of every commercial transaction. At the end of what had been a convivial if at times passionate evening of argument and debate the request was put to Wilberforce that he be the anti-slavery’s representative in Parliament?

The details of the role were left vague but though he listened with interest he remained non-committal for he was he was under no illusions as to the magnitude of the task should it be undertaken. He would be opposing not just the commercial vested interest but a landed aristocracy that had in large part seen its wealth restored by investments made in a business that in public they would shrug their shoulders at as if in apparent ignorance.

On 12 May, sitting beneath the large oak tree that dominated the grounds of his estate at Holwood discussing the slavery issue and the request made to him by the Committee with his friend Pitt and another future Prime Minister Lord Grenville, Wilberforce was still prevaricating when Pitt interjected: “William, why don’t you give notice of a motion on the subject of the Slave Trade? You have already taken great pains to collect the evidence and so are entitled to the credit that will come to you. Do not lose time, or the ground will be occupied by another.”

He had at last found the cause he had been looking for – his mind was made up.

On the 22 May, the first meeting of the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade took place delighted to have Wilberforce to campaign for them. But they were also disappointed that he declined to join the Committee itself. Despite this Wilberforce firmly believed that he had found a cause worth fighting for. He was to write: “My first years in Parliament I did nothing, nothing to any purpose, my own distinction being my darling object.” His campaign however would be delayed by ill-health possibly the result of a nervous reaction to the burden he now knew he had to bear. In the meantime, the anti-slavery campaign was given a boost with the publication of the freed slave Olaudah Equiano’s biography.

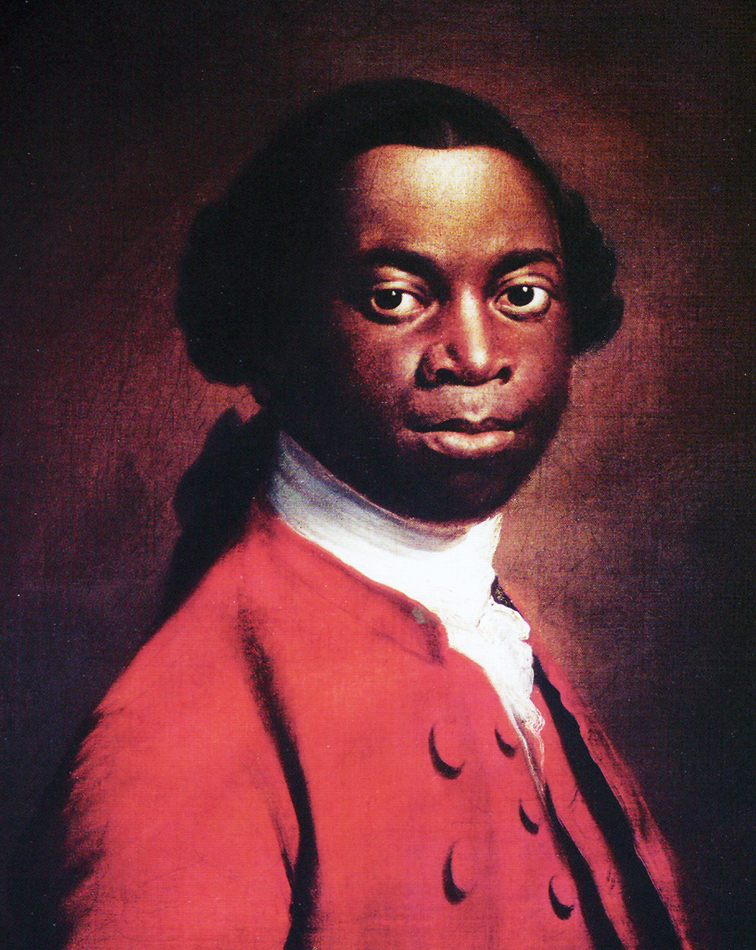

Equiano, who preferred to be known by his given name of Gustavus Vassa had either been taken into captivity from Africa when still a child or had been born into slavery in colonial South Carolina his own account and the evidence appear to conflict, had laboured on the plantations but had spent most of his time at sea where he had been sold several times.

His last master was Robert King, a Quaker who perhaps feeling pangs of guilt at owning a slave at all permitted Equiano to earn the money with which he could in time purchase his own freedom which he did in 1766, aged 21.

Equiano was to spend many more years at sea before settling in London where he felt safe from possible kidnap and an enforced return to slavery than elsewhere, particularly the Americas. In London he joined a group of fellow black men, freed and escaped slaves called the Sons of Africa formed to campaign against the slave trade.

The fact that there was a black campaign group within a heartbeat of the commercial centre of the slave trade was possible because of the many black grooms and valets in England and the thriving if small black communities in London and the other port cities.

Indeed, it was Equiano who first brought the case of the Zong to the attention of Granville Sharp and it was his vivid description of the conditions slaves were forced to endure, the sickness and disease, the punishments and savage beatings, and the slave auctions caused a sensation and sold many copies running through six editions in a very short time.

In the absence of Wilberforce from Parliament, William Pitt acted on his behalf cautiously introducing the motion for a bill on the abolition of the slave trade before concerned that he would lose support within the House of Commons were he seen as partisan, withdrawing from the issue.

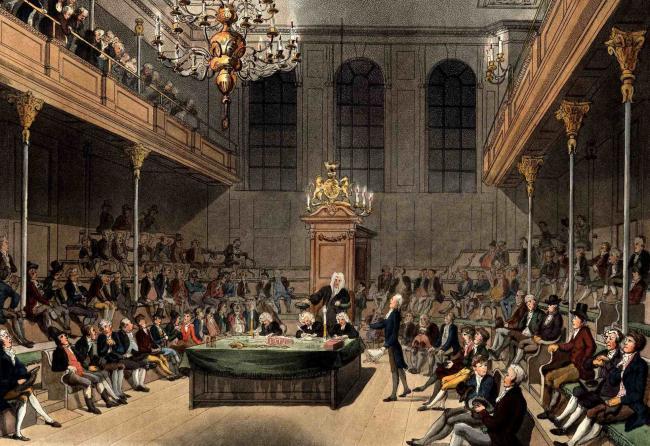

His health restored, on 12 May 1789, William Wilberforce stood up in the House of Commons to make his first great speech against the slave trade beseeching his fellow Members of Parliament to vote in favour of its abolition.

Adopting a tone of sadness at the injustice rather than one of anger or grievance he based his speech not merely upon a sense of moral outrage but evidence, the evidence so assiduously compiled over so many years by Clarkson, Sharp and others.

“I wish exceedingly, in the outset, to guard both myself and the House from entering into the subject with any sort of passion. It is not their passions I shall appeal to—I ask only for their cool and impartial reason; and I wish not to take them by surprise, but to deliberate, point by point, upon every part of this question. I mean not to accuse any one, but to take the shame upon myself, in common, indeed, with the whole parliament of Great Britain, for having suffered this horrid trade to be carried on under their authority. We are all guilty—we ought all to plead guilty, and not to exculpate ourselves by throwing the blame on others; and I therefore deprecate every kind of reflection against the various descriptions of people who are more immediately involved in this wretched business.”

He detailed the cruelties of the institution of people taken forcibly from their homes and separated from their families, the hardships of the voyage, the cramped conditions, the filth and disease, and the arbitrary use of punishment to maintain control. He exposed the lies that were peddled to mask these truths to spare the feelings of those concerned, to hide the facts that could only prick the conscience of humanity, and he appealed to the common decency of the slave traders themselves.

The speech concluded to a lukewarm reception followed by the suggestion that before any vote, be taken on the motion the evidence he had produced should be properly scrutinised in committee. Wilberforce agreed - a decision that was later criticised for having seriously impeded the anti-slavery campaign at a time when it appeared to have the momentum.

His opponents in Parliament led by the hero of the American Revolutionary War and MP for Liverpool Banastre Tarleton were delighted but if they thought Wilberforce’s decision had effectively mothballed the campaign, they were to be mistaken for he was to prove a determined and relentless adversary. Similarly, the aggressive pro-slavery lobby in Parliament were to fight a grim and protracted defence.

The moral case for the abolition of the slave trade had been made no doubt, but it was the opposition who had the Blue Books, the economic facts detailing the harm it would do to commerce, the letters and depositions of the plantation owners predicting economic ruin were any restrictions at all placed on the regular and safe delivery of robust slaves to replenish their always depreciating stock of labour.

But they too were willing to argue a moral case:

1) Servitude was the natural condition of the black race.

2) Slavery which had been in existence since antiquity was common to man.

3) With slavery came the benefits of Christian civilisation, the means by which the black race would eventually be freed from barbarism.

4) It was a pleasure to be in the service of a kind master and to be provided with all things

In truth it was a battle of Gods – the God of profit or the God of conscience.

Later in that year of 1789, revolution erupted in France and foreign affairs came to dominate Parliamentary procedure but nonetheless on 18 April 1791, Wilberforce once again introduced his bill in the House of Commons this time with an impassioned plea:

“Never, never will we desist till we have wiped away this scandal from the Christian name, released ourselves from the load of guilt, under which we at present labour, and extinguished every trace of this bloody traffic, of which our posterity, looking back to the history of these enlightened times, will scarce believe that it has been suffered to exist so long a disgrace and dishonour to this country.”

Despite the well-chosen words when the vote was taken the bill was rejected by 163 to 88, a scale of defeat that surprised Wilberforce, but it did not deter him and the following year he tried once again.

This time the Government proposed a compromise solution that would placate the slave owners but also lead to the slave trades gradual abolition. The motion was easily passed by 230 votes to 85 but Wilberforce was no fool and for gradual he read never. He was to remain largely silent on the issue but there was a sense that he had been sold out by Pitt and his colleagues.

Despite the Government attempt to side-line the issue in February 1794, Wilberforce returned once more to Parliament and this time his bill to abolish the slave trade was defeated by just 8 votes. It appeared the anti-slavery campaign had regained the momentum, but this was all about to change.

In April 1794, Revolutionary France declared war on Britain, a ruinously expensive conflict that was to see any proposal that interfered with British trade as an unpatriotic act and those who advocated it as dangerous radicals.

The opponents of abolition in Parliament now seized their opportunity and all decorum was brushed aside as orchestrated by Tarleton his supporters heckled and jeered those speaking in favour of abolition accusing them of being Radicals and Jacobins, an accusation that appeared confirmed when the National Convention in France abolished slavery and Wilberforce suggested to Pitt that he seek a peace settlement.

Accused of treason by Tarleton and his friends every time they rose to speak in the House the anti-slavery campaigners began to absent themselves from its proceedings. When Pitt ordered the arrest of those who had long been campaigning for Parliamentary reform on charges of sedition the message was clear.

By 1795, Wilberforce was exhausted and needed to rest, Clarkson suffering from ill-health had retired to the Lake District, the Committee for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade had ceased to meet, and many others had been intimidated into silence.

Wilberforce refused to yield to despair and continued to introduce his bill year on year but to waning public support and a much-diminished audience. The campaign to abolish the slave trade appeared moribund. It only revived in 1804, when Napoleon Bonaparte reintroduced slavery in the French colonies turning the campaign to abolish it in Britain from a treasonable act into a patriotic one.

The abolition of the slave trade would provide Britain with the moral high ground in a conflict they often seemed destined to lose. It would in effect be a war measure. Wilberforce also now had the new Prime Minister Lord Grenville (Pitt had died in 1806) firmly on his side.

Grenville decided to force the abolition bill through the House of Lords thereby overcoming its greatest obstacle first so that when Wilberforce introduced his bill in the House of Commons he would be doing so almost as a fait accompli.

On 23 February 1807, after ten hours of debate during which it seemed that Tarleton was now the lone voice it was announced that the bill had passed by 283 votes to just 16 as people crowded around a weeping Wilberforce to congratulate him.

Some now wanted him to push on and demand the abolition of slavery in its entirety but not wanting to jeopardise what had already been achieved he declined to do so.

The Slave Trade Act received Royal Assent becoming law on 25 March 1807, and it was to be rigorously enforced - between 1808 and 1860 the Royal Navy’s West Africa Squadron intercepted some 1,600 slave ships and freed more than 200,000 slaves. Those rulers in regions of British occupation or influence who permitted slave trading were forced to comply with the new law or face arrest and possible execution.

After 20 years of constant campaigning, broken promises, frequent rebuttals, and vicious mudslinging the evil of the slave trade had been eradicated from British commercial life. It would be far from Wilberforce’s only achievement, but it would always be his finest, though throughout he had rarely been free of criticism and not just from his opponents.

Despite the fact that his relationship with William Pitt was to sour somewhat he remained loyal to his old friend speaking in his favour and supporting him in Parliament which meant voting for repressive wartime legislation. Indeed, his politics often appeared not to mirror his commitment to social reform. Besides his opposition to the slave trade he also campaigned for animal welfare, legislation to restrict child labour, improved working conditions, and penal reform but at the same time he voted in favour of press censorship, the criminalising of trade unions and against Catholic Emancipation and an Inquiry into the Peterloo Massacre.

In 1821, Wilberforce handed over the reins of the anti-slavery campaign in Parliament to Thomas Fowell Buxton but remained its figurehead writing often in support of slavery’s abolition and from time to time once again taking up the cudgel of debate.

The last decade of Wilberforce’s life was blighted by ill-health and failing eyesight and though the argument against slavery had long since been won it appeared that he would not live long enough to see its formal abolition.

The 1832 Reform Act, of which he approved with some reservation, extended the franchise to many of the towns and cities of the industrialised north where abolitionist sentiment was at its strongest and many of their elected representatives to Parliament shared that sentiment.

In May 1833, the Whig Government introduced the Abolition of Slavery Bill to little formal opposition.

On 26 July, Wilberforce convalescing at home was visited by friends who informed him that the abolition of the slave trade throughout the British Empire was certain. Three days later aged 73, he died and was buried in Westminster Abbey not far from his friend William Pitt.

The Abolition of the Slave Trade Act was passed into law on 28 August 1833.

Tagged as: Georgian

Share this post: