Wild Bill Hickok

Posted on 18th May 2021

Wild Bill Hickok is perhaps the most famous gunfighter to emerge from the Old West whose fame spread far beyond the shores of the American Continent. Yet despite his reputation as a ruthless killer and a man not to be messed with, he started life on the side of the so-called angels.

He was born James Butler Hickok on 27 May 1837, in the town of Homer, Illinois. He was one of seven children from a respectable family of God-fearing Baptists and along with his siblings he would attend Church regularly.

His father, William Hickok, was an active anti-slavery man and the family farm was often used as a stopover on the underground railway, or the route used by abolitionists to spirit runaway slaves from the Deep South to freedom in Canada and the North and it is believed by some that the future Wild Bill who had always displayed a keen interest in guns had learned his skill as a marksman protecting his father from slave hunters.

It wasn’t until 1855, that the eighteen year old James Hickok first found himself in any serious trouble and it was an incident that was to change his life when in an argument with another young man James Hudson, angry words soon escalated into a full-blown fist fight which saw Hickok knock his opponent unconscious. Believing that he had killed Hudson, he took what he thought was a lifeless body and threw it into the canal. He then mounted his horse and fled to Kansas where he joined the Free State Vigilantes, the anti-slavery Army of General James Lane, and fought in the bitter struggle that was to earn the State the name Bleeding Kansas.

Admired for his leadership skills his reputation soon spread and earned him the job of Constable in the town of Monticello.A physically imposing figure with the attitude to match Hickok appeared the perfect man to impose law and order on a town where it was required but he had a temper and a ruthless streak that went well beyond the bounds of legality.

On 16 December 1861, David McCanles, along with his 12-year-old son and two other men, James Woods and James Gordon, visited Rock Creek Station to demand the payment of money he was owed on a property sale. The argument with the Station Manager Horace Wellman soon turned violent and in the ensuing scuffle McCanless and the other men were forced to leave the office by Hickok who was there to protect Wellman.

McCanles however, was not willing to leave it there and hurled insults at Hickok from the street. As people were soon to discover it didn’t do to insult James Butler Hickok. When he refused to come outside McCanles and the other men re-entered the office where Hickok emerging from behind a curtain began firing. McCanles was killed instantly, Woods and Gordon died later of their wounds. They were the legendary Wild Bill Hickok’s first recorded victims.

He was tough and uncompromising, and it was clear that as long as he was the law there would be little disorder but he wasn’t always admired, “a ruffian by nature, a drunken, swaggering fellow, who delighted when on a spree to frighten nervous men and timid women.”

He did not remain long in Monticello following the McCanles shooting but moved onto work as a guide on both the Sante Fe and Oregon Trails.

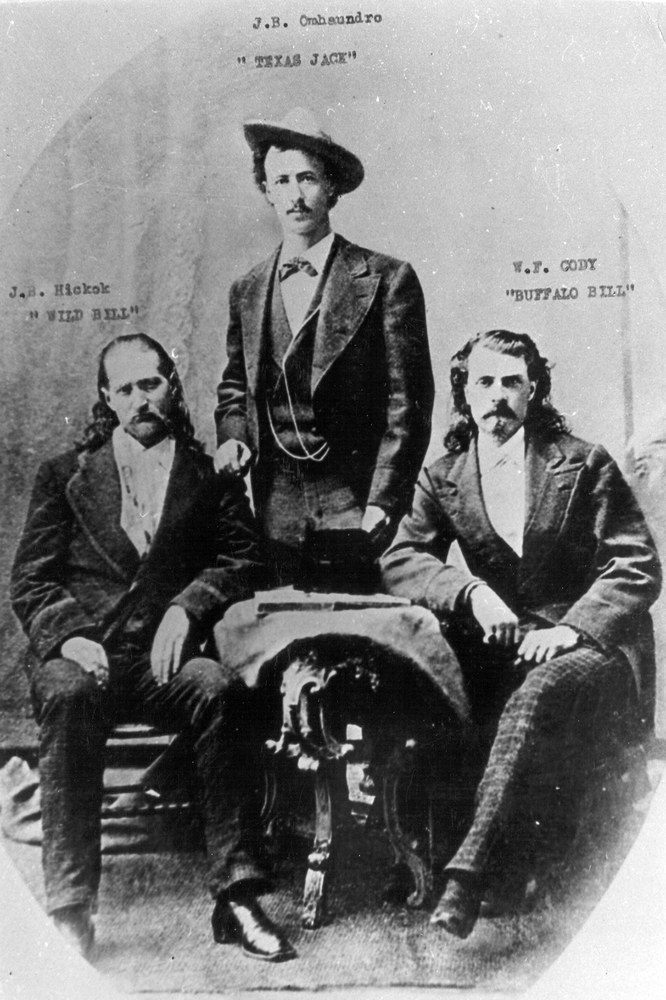

During the Civil War he served as a wagon-master and later as a scout in the Union Army serving mostly in the fratricidal struggle that tore apart the States of Kansas and Missouri. It was fight where the rules of war simply did not apply and where prisoners taken were regularly executed. It taught him that there were few depths to which a man would not stoop and that just how few could be trusted. Serving alongside him was a fellow scout, Buffalo Bill Cody, who would become a lifelong friend.

On 10 August 1861, he fought at the Battle of Wilson’s Creek in Missouri. It was a bloody affair in which the Union Army he was serving with were routed and he later wrote home to his brother how terrified he had been at the booming of the cannon. It was the only time that he ever admitted he was scared.

Previously known as ‘Duck Bill’ because of a protruding upper lip that he hid with a moustache it was during his time in the army that he received the name Wild Bill when he saved a man from being lynched in a saloon in the town of Independence. As he was leaving with the man he had just rescued a woman shouted, “Good on you, Wild Bill,” and the name stuck.

Following the conclusion of the Civil War Wild Bill moved to Springfield, Missouri, where he was to meet for the first time his future lover the 17-year-old Martha Jane Canary, who would become better known in later life as Calamity Jane.

On 21 July 1865, he got into an argument with an ex-Confederate soldier Davis Tutt who he had earlier befriended, but it was a friendship born of necessity not of affection. Both men had been army scouts on opposing sides during the Civil War and in the same zone of conflict and there existed a desire on both parts to humiliate the other should the opportunity arise.

For the previous few months Hickok had been leeching off Tutt to whom he now owed a great deal of money. Tutt now wanted his money back. During a card game Hickok, who was having a bad night, placed his much-cherished pocket watch on the table to use as a bargaining counter should his money run out. Tutt, who was present, took Hickok’s watch saying he would keep it as collateral for the unpaid debt.

Hickok, who acknowledged the debt but not the amount owed, warned Tutt to not be wearing the watch next time he was in town. He knew however that the watch provided Tutt with the opportunity to humiliate him in public and he also knew that he would take the opportunity. That night he polished and oiled his Navy Colt revolvers in preparation for what he knew would be a showdown the next day.

Tutt did not appear on the street until 6 pm the following night and having been informed that Tutt was wearing his pocket watch, Hickok went outside to confront him. Tutt was proudly showing off the watch to onlookers when Hickok shouting from a distance reminded him of his warning of the previous night. Tutt merely laughed and began to walk towards Hickok who said, “Don’t come any closer, Dave,” and took up a sideways duelling stance. It was obvious there was going to be a showdown and the crowd began to disperse and take cover.

The two men eyed each other for a moment and then drew each firing almost simultaneously from about 75 yards. When the smoke cleared Hickok was still standing while Tutt lay dying on the street shot through the heart. He had fired wide, Wild Bill who always remained calm and rarely missed, hadn’t.

Hickok was arrested and put on trial for murder, but it was evident to everyone that it had been a fair fight and he was cleared of any wrongdoing. Despite his acquittal Hickok thought it best to leave Springfield which he believed was a viper’s nest of Confederate supporting rebels. In what was now to become an increasingly itinerant lifestyle he travelled to Dakota where he served for a time as a scout for George Armstrong Custer’s Seventh Cavalry.

As a man who never hid his hatred of Indians, he was happy to serve Custer in his campaign against them and it was during his time with the 7th Cavalry that he got to know Custer’s wife, Elizabeth, who wrote of him: “Physically he was a delight to look upon. Tall, light, and free in every emotion, he rode and walked as if every muscle was perfection.”

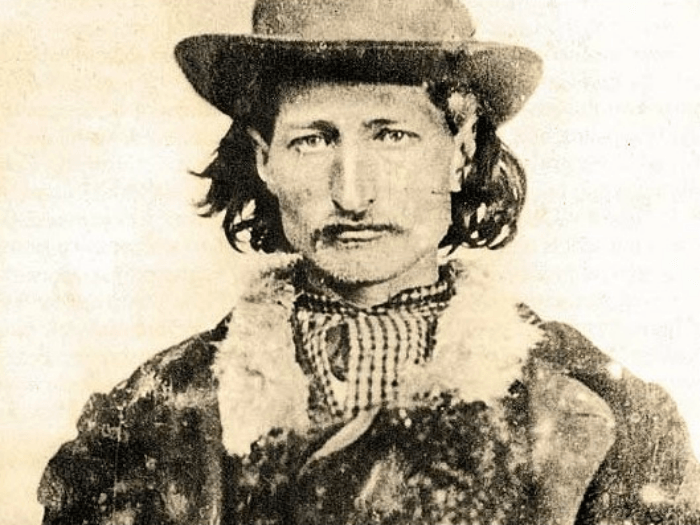

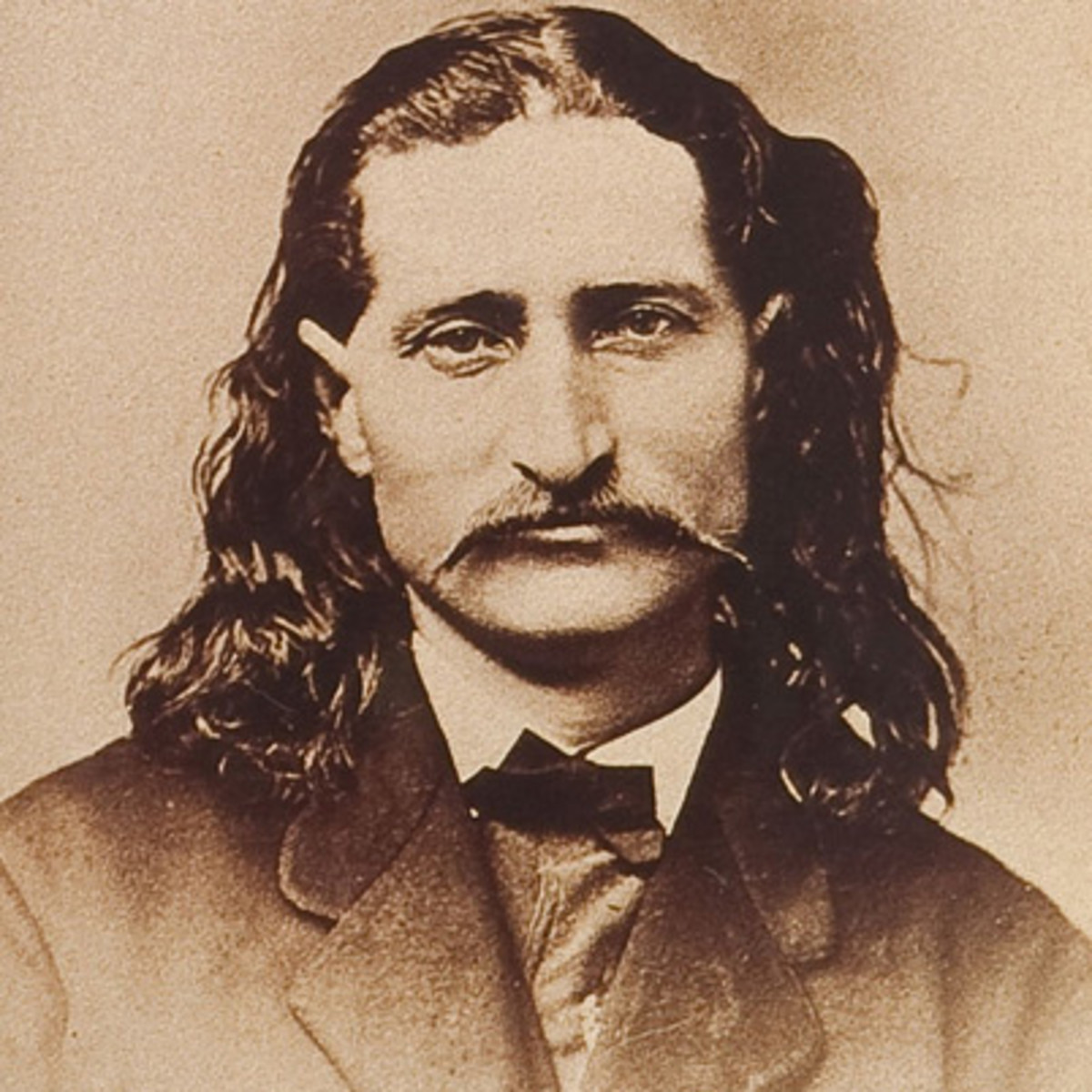

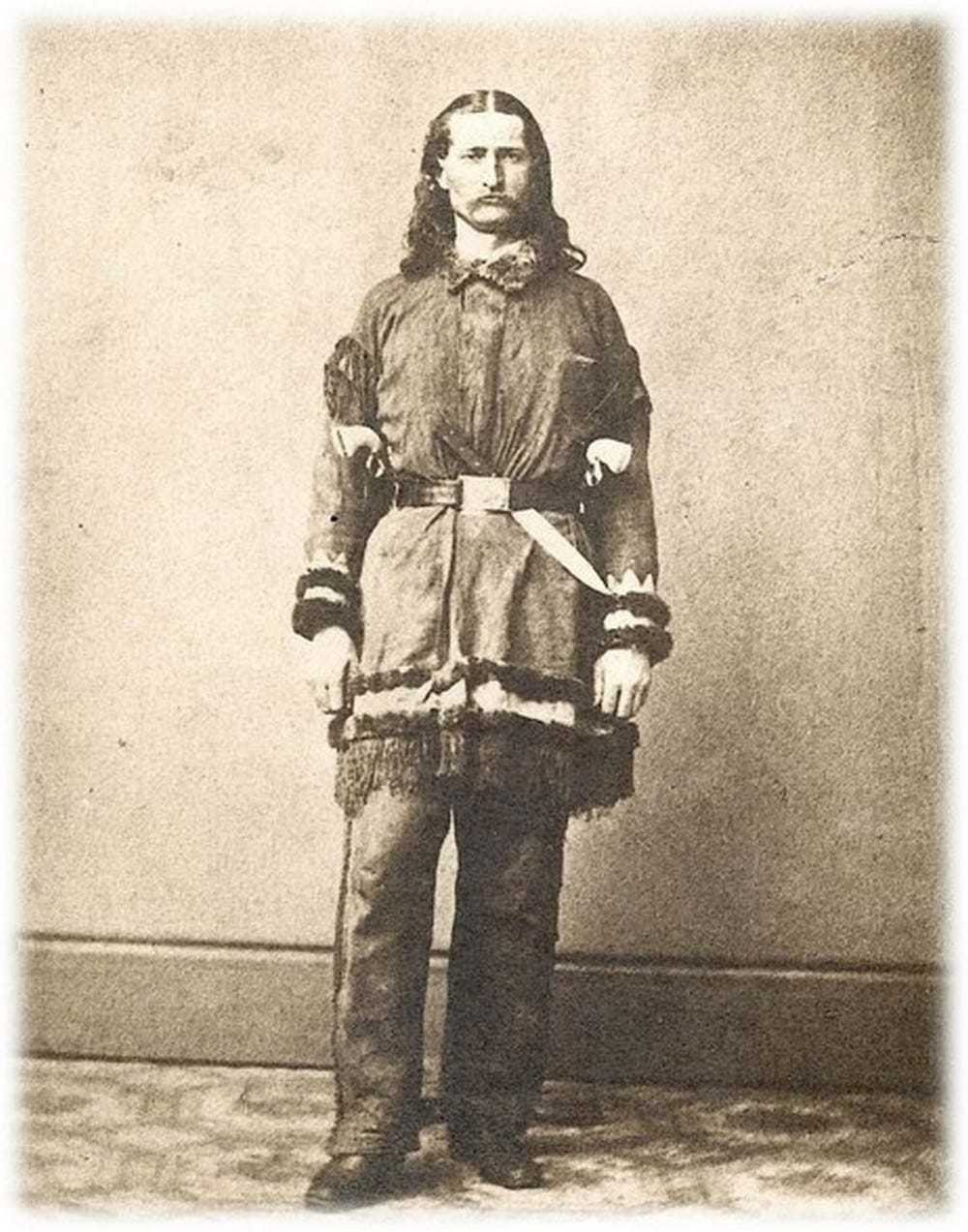

In truth, Wild Bill’s physical appearance belied his fearsome reputation.

Long-limbed and slight at 6’1” he was taller than most men and was so graceful in his movements that with his long auburn hair tinged with red and gentle soporific eyes he had an almost feminine mien. He was also quietly spoken rarely raising his voice except in anger though it was said that his expression could change in an instance, that his clear blue eyes would narrow, and a darkness would descend that was frightful to behold.

Still unable to settle he moved back to Hays City, Kansas, where he was appointed Sheriff but his stay there was to be brief after he killed two men, Bill Mulvey and Samuel Strawhun in separate gunfights.

In 1867, Hickok was interviewed by Colonel George W Nichols of Harper’s Magazine who he told, perhaps tongue-in-cheek, of the more than hundred men he had killed. Nichols however reported it verbatim, and the story was later picked up by Henry Morton Stanley who was working for the New York Daily Herald and would later find fame himself as the man who discovered the famous explorer Dr Livingstone. As a result of Stanley’s intervention, the story was syndicated nationwide and almost overnight Wild Bill Hickok had become one of the most famous and notorious men in America. Now at the height of his fame he was rarely out of the newspapers and dime novels detailing his exploits sold in the thousands.

Wild Bill was happy to burnish his reputation with evermore outrageous tales of derring-do and in photographs he now posed in buckskins with his six guns on display and an unsheathed Bowie knife tucked into his belt.

Hickok now linked up for a time with his old friend Bill Cody who was making a lucrative $500 a month selling buffalo meat to the army but Wild Bill was never very keen on anything that involved work and shooting buffalo bored him – they soon parted. Rather, as an inveterate gambler he wanted something that would give him the time to play poker and so on 5 April 1871, he agreed to become Marshal of the town of Abilene in Kansas.

Abilene was a tough, lawless town but one that was in transition, and it was both a staging post for the rough cow-hands that rode the trails and a place of respectable citizens seeking a quiet life.

Hickok, who was more at home in the brothels and saloons of the rough side of town and spent much of his time playing poker did little to control the activities of those seeking a good time, but he did guarantee that the two sides of the town were kept apart. If anyone stepped out of line, they were dealt with harshly.

During his stay in Abilene, Hickok fell out badly with saloon owner Phil Coe. The cause of their antagonism remains obscure, but Coe was an arrogant man with a high opinion of himself who may have resented Hickok’s fame and notoriety. Also in town at this time was John Wesley Hardin, the psychotic gunman who is known to have killed some 27 men during his lifetime, though he was to claim many more.

He had been born in Texas and had often expressed his regret that he had been too young to fight for the Confederacy. As such, he was approached by Coe who tried to coax him into confronting Hickok who he said picked on southerners and ex-Confederates. But Hardin, who got on well with Hickok, was not just an admirer but wary of him. He told Coe to go his own way.

Not long after Hardin fired through the ceiling of his hotel room after being awoken by the snoring of the man who was staying in the room above. The man was killed outright, and Hardin was forced to flee in the dead of night with Hickok in hot pursuit.

The dispute between Hickok and Coe continued, however.

One day boasting of his prowess with a pistol Coe turned to Hickok and said, “I can kill a crow on the wing.” To which Hickok famously replied, “Did the crow have a pistol? Was it firing back? I will be.” A confrontation was now inevitable.

Not long after these words were exchanged Coe confronted Hickok on the street and in the ensuing argument fired several times at Hickok but missed. Wild Bill fired just once and shot him dead. Just after he did so someone rushed from the crowd shouting his name, Hickok turned around and fired killing the man instantly. It was his Deputy and close friend Mike Williams who had rushed to the scene to help him. Hickok was distraught and ushering all the onlookers away he knelt over the body and wept. Later that night he rampaged through the rough side of town closing the saloons and brothels and violently confronting anyone who tried to stop him.

He never really got over having killed his friend and to rub salt into the wounds a few weeks later the Town Council, concerned that their Marshal was no better than the men he was protecting them from, dismissed him from his post. Unable to remain in Abilene, Hickok for a time wandered aimlessly from town to town playing poker to make ends meet. But he was rarely out of trouble and in a bar room brawl with three other men he beat them so severely that one later died of his injuries.

Despite his short temper many considered him to be a placid man, but he was not someone who would endure an insult and his reputation ensured there was always someone looking for fame and willing to chance their arm.

In late 1871, he teamed up again with his old friend to make his acting debut in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show, but his stage career was brief and undistinguished and he soon returned to the itinerant lifestyle he had become accustomed to. During his travels he met and married a 50-year-old circus entertainer, Agnes Lake Thatcher, even though it was widely rumoured that he was already married to Calamity Jane and that she had borne him a child.

But by now, though only being in his late thirties Wild Bill’s health was beginning to fail him and thinner and less mobile than he had once been the years of rough living and heavy drinking had taken their toll. Also, he had made little money from his fame and the press had in recent years moved onto new heroes of the frontier. His star was fading fast, and he was even arrested for vagrancy on a number of occasions.

In early 1876, Hickok, who had been having trouble with his eyesight visited a doctor in Kansas City who diagnosed him with glaucoma, a deteriorating disease of the eye that would eventually render him blind. Indeed, some who knew him at the time said that in bad light he could barely see at all and that at night he would often have to be led home on someone else’s arm.

Hearing the news gold had been discovered in the Black Hills of Dakota, Hickok decided to try his hand once more at prospecting and joined a wagon train heading west. No one knows for sure if he had a premonition of the fate that awaited him but before he left, he wrote to Agnes: “If we should never meet again, while firing my last shot, I will gently breathe your name.”

Hickok’s old aversion to physical labour soon re-emerged and so his prospecting for gold was not a success. He soon returned to his favoured way of making a living, the poker table.

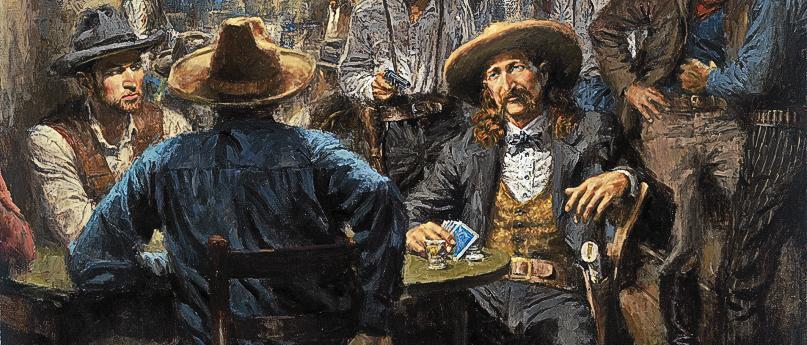

Resident now in the town of Deadwood deep in the heart of the Black Hills he became a regular player at Saloon No 10. On the afternoon of 2 August 1876, he joined a game already in progress so wasn’t able to get his usual seat where his back would be to the wall, and he could see everyone who came and went. Not long after he started playing John McCall, a buffalo hunter, entered through the door to Hickok’s rear and shouting – Take That! Shot him once through the back of the head. Wild Bill Hickok, the Legend of the West, died instantly.

McCall made no attempt to flee town but rather stayed to make the most of his great deed and was subsequently arrested and put on trial for his life. He was to claim that he shot Hickok because many years before he had been responsible for the murder of his brother and a man by the name of Lew McCall had indeed been killed in Abilene, though it is not known by whom.

The Jury was inclined to believe that a notorious gunman such as Wild Bill Hickok must have brought dire retribution upon himself and McCall was acquitted. The Court was not legal however, in what was still officially Sioux territory. Nevertheless, McCall might still have got away with murder had he not boasted to any and every one about what he had done. Hickok’s friends demanded a retrial which was granted and held in the town of Yankton.

McCall who showed no remorse at his trial and indeed complained that he was not receiving the recognition he deserved was this time found guilty and sentenced to hang. Even as he stood upon the scaffold awaiting execution he continued to boast of his great deed.

Following his death an old friend of Hickok’s, Captain Jack Crawford who had served with him during the war and kept in contact thereafter wrote: “Wild Bill had his faults, grievous ones, perhaps. He would get drunk and indulge in the licentiousness characteristic of the border in the early days, but he was as gentle as a child unless aroused to anger by intended insults. He was loyal in his friendships, generous to a fault, and invariably espoused the cause of the weaker against the stronger in any quarrel.”

The hand that Wild Bill Hickok had been holding that fateful late afternoon in the summer of 1879 was two Black Aces, two Black Eights, and an unturned Queen of Hearts known ever since as – Dead Man’s Hand.

Tagged as: Miscellaneous

Share this post: