William Wallace

Posted on 12th April 2021

William Wallace was a man driven by his hatred of the English and their presence in his country, so he fought them whenever and wherever he could winning a decisive victory at the Battle of Stirling Bridge that for a brief time made him de-facto ruler of Scotland; and it was his courage, his unrelenting opposition to English interference in the affairs of his homeland and his role in the Scottish Wars of Independence that has since seen his legend grow until he is now often spoken of in the same breath as Robert the Bruce.

He was born sometime in the 1270’s the exact date remains unknown, in Elderslie, Renfrewshire and was not raised in poverty as has often been suggested but in a genteel manor house as the son of Malcolm Wallace*, a nobleman who owned several significant if not particularly large estates. When his father and his elder brother John were killed in a skirmish with English soldiers at Loudon Hill in 1292, he went to live with his uncle where he continued his education becoming fluent in French and Latin and learning the arts of war that were expected and required of a Knight of the Realm.

Scotland at this time remained an independent country but one that had been in turmoil since 1286 and the death of King Alexander III. He had no surviving children, so the Scottish nobility declared his only grandchild, the four year old Margaret, Maid of Norway, his successor. Edward I, King of England, was quick to take advantage of the situation and negotiated the betrothal of his son, also Edward, the Prince of Wales, to Margaret. Though in doing so he had been made to consent to the Treaty of Bingham and thereby promise to preserve Scottish law, customs, and independence.

But Scotland was to be plunged into further disarray three years later when the now seven-year-old Maid of Norway died and the contending parties for the throne were immediately at each other’s throats. To prevent Scotland descending into chaos and civil war the nobility approached Edward to act as independent arbitrator and make the final decision on their behalf. Whatever he decided would be binding on all parties, including Edward himself.

There were many claimants to the throne but in the end the choice came down to just two, the Balliol family or the Bruce family. Both had strong claims, but in the end, Edward decided that the Balliol's claim was senior in genealogical primogeniture if not by proximity of blood.

On 17 November 1292 at Berwick-Upon-Tweed, Edward announced his decision; two weeks later on 30 November at Scone, John Balliol was crowned King of Scotland - it was to be a short reign and an unhappy one. He was not a strong enough man and was to prove himself incapable of standing up to his more powerful neighbour Edward who soon determined that he could bully him into being little more than his vassal in Scotland. So much so in fact that Balliol soon became known derisively as Toom Tabard, or Empty Coat.

If ever he stepped out of line he would be ordered to appear before Edward's Court in London where he would be subjected to one of the King's notorious rages and like so many before him he cowed before the furious Longshanks so known because of his great height.

Balliol was treated with utter contempt by Edward who often publicly belittled and humiliated him. After one such torment in March 1296, he returned to Scotland only to be humiliated once more but this time by the Scottish nobility which forced him to renounce his homage to the English King.

Edward's response was swift and decisive raising an army and marching on Berwick then Scotland's most populated city and the hub of its commercial activity he took his revenge, the town was ransacked and burned and those who could not flee in time put to the sword. Indeed, so great was the slaughter it was said the killing only stopped when Edward himself witnessed the baby of a pregnant woman being torn from its mother's womb. Those Scots who had survived the initial bloodbath were then cleared from the town and it was repopulated with Englishmen from Northumbria. It has remained south of the border ever since.

Edward then proceeded to rout a hastily formed Scottish army at the Battle of Dunbar and in July 1296 in a public ceremony he forced King John Balliol to abdicate. Scotland would now be run by Englishmen appointed by Edward. In the meantime, he had removed the Stone of Scone upon which Scottish Monarchs had traditionally been crowned and the Royal Seal and taken them back to London, remarking as he did so: "It does one good service to rid himself of a turd.” It seemed that Scotland's days as an independent sovereign nation were over.

William Wallace had by this time already acquired a reputation for violence, as early as 1292 he had knifed to death the son of Lord Selby for which a warrant for his arrest had been issued but was never enforced. He also later killed the son of the English Governor of Dundee over the continuing harassment of his family.

On one occasion he was approached by some English soldiers in the marketplace at Lanark who accused him of having poached the catch of fish that he had been intending to sell and demanded that he hand it over. He refused but having a surplus anyway offered them half. They insisted that he relinquish the entirety of his catch, or he would be arrested and the argument soon descended into a brawl during which Wallace killed two of the soldiers before the others ran off.

William Wallace was proving a dangerous man to cross but he remained elusive and so unable to apprehend him other means of punishment had to be found. In May 1297 learning of Wallace's recent marriage, William de Heselrig, the English High Sheriff of Lanark ordered the arrest and execution of his bride Marion Braidfute. Already a fugitive from the law Wallace had no hesitation in slitting de Haselrig's throat.

Vengeful, uncompromising and violent William Wallace was not a man to be meddled with and if anyone was willing to fight it was him.

Despite the forced abdication of King John Balliol and the country being awash with English soldiers Scotland remained in a state of rebellion even if most of the 1800 or so Scottish Nobles many of whom had been captured at the Battle of Dunbar had since renewed their pledge of allegiance to Edward and had been richly rewarded for doing so.

It was in large part an uprising of the common people and by late 1296 William Wallace had raised a small army of his own from those who had rallied to him in Selkirk Forest.

Meanwhile, in the Highlands, the Earl of Moray was waging a guerrilla war against the English that was so successful he had made the region effectively ungovernable. He had already captured Inverness and Urquhart Castle when he decided to march his forces south. At the same time Wallace decided to march his army north. They were to meet at Stirling where they decided upon a joint-command and to lay siege to the Castle.

They knew that Stirling Castle was the symbol of English power in Scotland and that they would have to come to its relief. On 11 September 1297 an English Army under the command of John de Warenne, the 7th Earl of Surrey, descended on the town. His force of 3,000 Knights and 8,000 Men-at-Arms greatly outnumbered the 3,500 Scots who sallied forth to confront them and seeing the forces arrayed against them many Scots were reluctant to fight.

It may have appeared to be a hopeless situation, but Wallace and Moray had carefully laid out plans and Wallace was determined that there would be a fight no matter what. When two Dominican Friars were sent by the English to negotiate a Scottish surrender they were told by Wallace in no uncertain terms: "We are not here to make peace but to do battle, defend ourselves and liberate our Kingdom. Let them come on, and we shall prove so in their very beards.” These were well chosen words intended to provoke the English and they worked like a dream.

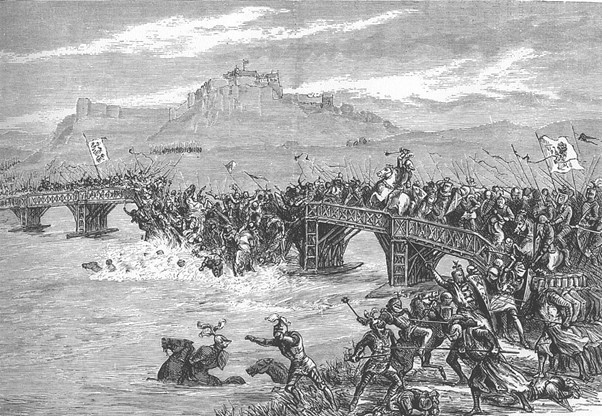

John de Warenne was an indolent and arrogant man who'd had to delay his own battle plans because he had overslept and certainly wasn't going to tolerate being spoken to in such a manner by some jumped up colonial subject of the English Crown. Outraged by Wallace's impertinence de Warenne sent his army across the bridge that separated them from the Scots. But at some points the bridge was so narrow that only two people could cross at a time, the logjam that quickly ensued caused chaos in the English ranks. Moray and Wallace who had invested the bridge with their troops allowed about half of the English army to cross before they attacked.

Taken completely by surprise the English fled in panic and many were cut down while others drowned in the river in their desperation to escape.

De Warenne responded to this setback by sending in his heavy cavalry, but these were easily repulsed by the Scottish schiltrons or tightly packed squares defended by 15 foot stakes jammed into the ground. The Knights forced to retreat rode down the infantry behind and even though half of the English army had yet to be committed to battle de Warrenne seeing the disaster unfold before his eyes could not flee quick enough.

One of those who had been killed in the fighting was Hugh de Cressingham, the hated Lord Treasurer of Scotland. It is said that Wallace ordered his body to be flayed and then had a belt made for his sword from a strip of the torn skin.

At least 5,000 Englishmen had been killed at the Battle of Stirling Bridge in what was an overwhelming and decisive victory for the Scots, and in the midst of the fighting had been seen William Wallace wielding a massive 5-foot-long broadsword. The Earl of Moray had been mortally wounded during the battle and died some weeks later.

William Wallace was described at this time as being: “A tall man with the body of a giant, cheerful in appearance with agreeable features, broad-shouldered and big-boned, with belly in proportion pleasing in appearance but with a wild look.”

Following his victory at Stirling Bridge Wallace despite being a Balliol man was knighted by Robert the Bruce and appointed Guardian of Scotland. In the absence of a King, Wallace as de facto leader of Scotland was determined to take the war to the English and so he invaded the most northern regions of England ravaging much of Northumberland and advancing as far south as Newcastle - if Edward could rampage across Scotland with impunity then he could do the same in England.

Edward I, who had been campaigning in France at the time of Stirling Bridge was quick to return to London and demanded that the Scots Commissioners present themselves at Court and renew their homage. When they refused to do so he denounced them as traitors and ordered his army to assemble at Roxburgh. This time Wallace would not be facing a subordinate of Edward's but the King himself who had assembled a powerful army of 3,000 knights and 12,000 infantry. He also had in his ranks a great many Welsh Long-bowmen while Wallace could muster only 6,000 men, almost all of whom were foot soldiers.

The disparity between the two armies could not be starker but then Wallace had no intention of confronting Edward, instead he adopted a scorched earth policy. All crops, livestock, and even places of shelter in the path of Edward's army were destroyed as at the same time his supply lines were cut and his baggage train harassed.

As a result of Wallace’s strategy, Edward's army began to starve and reports of dissent within the English ranks soon reached the Scottish camp. Wallace now moved his army closer to the English with the aim of pursuing them on what he believed would be their inevitable retreat out of Scotland. But he strayed a little too close and when on 1 April it was reported to Edward that Wallace's army was within ten miles of his own camp at Falkirk, he was heard to exclaim: "Then he need pursue me no more for as God lives, I will meet them this day".

Wallace was inclined once more to withdraw but those few Scottish Nobles present, and in particular John Comyn who commanded the Scots cavalry, demanded he stand and fight, to turn and run in the face of their enemy would be an act of the most shameful cowardice, they said. Wallace, who needed little encouragement to fight, formed his troops into four tightly packed schiltrons and waited for the English army to come on. He did not have to wait long.

Still smarting from the defeat at Stirling Bridge and the humiliation of Wallace's invasion of England the English knights charged with great gusto but were to be shattered on the 15 foot pikes of the schiltrons and forced to retreat. Likewise, Edward's infantry were also repulsed in fierce and bitter fighting that saw Wallace's entire advance guard wiped out.

Edward remained unperturbed by these early setbacks for he had kept in reserve his secret weapon, his Welsh bowmen. With total disregard for the safety of his own troops many of whom were still engaged with the enemy and would be in the line of fire he ordered them to unleash their arrows and continue to do so until gaps appeared in the Scottish schiltrons that could be exploited by his infantry.

In response to the murderous rain of arrows Wallace ordered those commanding the few cavalry he had, to attack and disperse the bowmen but instead they began to flee the field and despite increasingly desperate protestations to do so would not return. Wallace's men were by now falling in great numbers and what had been a closely fought battle soon became a rout. Those who could, including Wallace himself, escaped into nearby woods but more than 2,000 Scots had been killed along with a similar number of English.

William Wallace's reputation as a battlefield commander never recovered from his defeat at Falkirk and those among the nobility who had never truly reconciled themselves to Wallace, a social inferior as their ruler now turned against him and in September 1298 he was forced to resign as Guardian of Scotland.

Unlike the majority of the nobility who wanted to make peace with Edward, Wallace was determined to continue the fight and, in the winter of 1298, along with a friend William Crawford, he travelled to France to plead with King Philip IV for assistance in the struggle for Scottish independence but despite a stream of fine words and broken promises no help was forthcoming. By 1303, he was back in Scotland and continued to harass and ambush English troops from his base in Selkirk Forest, but he never again had the strength to wage war.

Edward, aware that Wallace was active again in Scotland was determined to bring the brigand to justice. By 1303, the Scottish Nobility had made its peace with Edward among them Robert the Bruce. With the nobility against him and the country crawling with English troops Wallace could not remain at liberty for long. On 5 August 1305, he was captured by troops loyal to the Scottish Noble John de Monteith, who it is believed on the orders of the Bruce handed him over to the English.

With no one willing to speak on his behalf, the victor of Stirling Bridge and the former Guardian of Scotland was taken to London without so much as a murmur of protest.

On 23 August, William Wallace stood trial at Westminster Hall charged with treason during which he only once spoke in his own defence and that was when the charge of treason was read out and he indignantly shouted at the Court: "I cannot be a traitor, for I owe him no allegiance, he is not my Sovereign, he never received my homage, I am a subject of King John Balliol".

He was right of course, for no one had been as steadfast and unwavering in their resistance to Edward I than William Wallace. Whether he had ever at any point pledged his loyalty to Edward troubled the Court not at all and he was found guilty of treason as expected.

Later that same day he was stripped naked, forced to wear a laurel crown and dragged through the streets of London to Smithfield as a crowd furious at Wallace the butcher and Wallace the baby-killer, closed in and jeered, abused and spat upon him. On the scaffold he was asked if he wished to confess his sins and ask the forgiveness of both God and his King, but he said nothing in reply.

He was then hanged until barely conscious before being cut down and having his entrails removed and then burned before his own eyes. Still alive, he was then beheaded before his body was quartered and the various parts distributed around London for public display.

It was a slow and agonizing death in which those watching took great delight. Many years before his uncle had told him, “Of all things freedom is most fine. Never submit to live in the bonds of slavery entwined. At least that pain was spared him for William Wallace never did.

* The reverse side of his official seal suggests he was in fact the son of Alan Wallace and therefore the grandson of Malcolm Wallace, or the second son of a second son.

Tagged as: Ancient & Medieval

Share this post: