World War One: The Last Days

Posted on 4th June 2021

By 20 July 1918, the last great German offensive on the Western Front had failed and having suffered 688,000 casualties including 270,000 dead the morale of their desperately tired and half-starved troops was close to collapse.

On 8 August, the Allies launched a massive offensive of their own and before long a 12-mile gap had appeared in the German lines, 18,000 prisoners taken, and 330 guns captured. It was, said General Ludendorff: “The Black Day of the German Army.”

Their resolve would stiffen but their capacity for offensive action had been destroyed. It marked the beginning of the end.

On 26 September, the Allies attacked once again and broke through the supposedly impregnable Hindenburg Line and despite often stiff resistance it was becoming increasingly apparent to the German High Command that the Army was beginning to disintegrate and was close to collapse. On the Home Front the situation was even worse.

The Allied blockade of German ports had led to mass-starvation throughout the country and strikes had paralysed most of her major cities. Ludendorff knew the war was lost and that he could no longer prevent the invasion of his homeland and he feared not just the rout of the German Army but a Bolshevik Revolution in Berlin. He declared that there must be an immediate cease-fire, but he also wanted the Civil Administration to take responsibility for it.

The German Government approached the Allies as early as the first week of October seeking an armistice based upon the American President Woodrow Wilson’s Fourteen Points of the previous year. The Allied High Command refused to negotiate insisting that their terms for an armistice must be accepted unconditionally.

So, the war continued, but the more time passed the more untenable the German situation became with even her Allies now deserting her. Bulgaria had changed sides in September, on 30 October the Ottoman Empire surrendered, and four days later on 3 November the rapidly disintegrating Austro-Hungarian Empire agreed to lay down its arms and sign a separate peace.

On the night of 29 October, the sailors of the Kriegsmarine stationed at Kiel and Wilhelmshaven refused to take their ships out to sea in an attempt to break the blockade on what they knew was a suicide mission. Discipline had effectively broken down and the fleet was in a state of mutiny – The Revolution had begun.

In Berlin, the Kaiser fantasised about triumphantly leading his troops into his capital city to reclaim its streets from Bolshevik revolutionaries. Detached from reality he had already effectively been side-lined but still he stubbornly refused to abdicate so on 9 November the Government simply announced that he had. He now fled in haste to the Netherlands.

On the Western Front meanwhile the German Army with food scarce, ammunition short and morale low remained intact if stretched almost to breaking point with troops surrendering in ever greater numbers and desertion commonplace.

Free now of the Kaisers interference and with the Army effectively abdicating responsibility the new Government again approached the Allies seeking a ceasefire. They agreed to meet on 8 October in a train carriage in the Forest of Compiegne some 40 miles north-east of Paris. But it would be a meeting on the Allies terms.

The German delegation to the talks was headed by Matthias Erzberger, a centre-right politician who though a patriot had been a long-time opponent of the war. His colleagues were also for the most part civilian - it seemed that the German Army so desperate for a truce was not willing to endure the humiliation that came with requesting one.

It was of course, a mistake by the Allies not to demand that the German Army be seen to endorse the peace terms or indeed to invade and occupy Germany itself. Both were to have serious repercussions for it allowed the lie to be peddled that the Army had never been defeated but had instead been stabbed in the back by duplicitous ‘Jewish’ politicians at home.

There was, however, not a great deal to negotiate. Erzberger, whose remit was to seek an honourable peace, was soon told he must accept the terms for Armistice offered if he did not the Allied Supreme Command was content to continue the war, all the way to Berlin if necessary. Despite being served the best French cognac the atmosphere was frosty.

The terms of the Armistice called for the German Army’s disarmament, the German Navy’s internment, the occupation of the Rhineland, and her agreement to accept culpability for the war and all the carnage wrought. The blockade of Germany that had seen millions of its people reduced to starvation would also continue until a formal peace agreement was reached – it was, take it or leave it. Erzberger was both stunned and dismayed and after just 45 minutes the meeting broke up.

This was not an armistice it was unconditional surrender and Ludendorff now called for hostilities to be resumed, but this was impossible. The Germans had been given 72 hours to sign the Armistice Agreement, or by 11 am on 11 November. If they did not sign the Allies would resume the advance with all the force at their disposal.

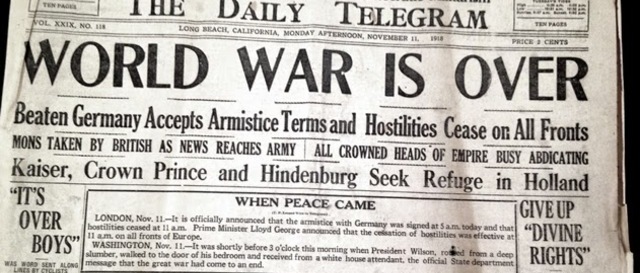

At 5.10 am on 11 November a sullen and morose Erzberger signed the Armistice Agreement. It was to come into effect at 11.00 the same day.

As news of the Armistice began to filter through the need for both sides to dispose of their remaining artillery shells became a matter of urgency. It was also a last opportunity to batter the enemy one last time and a furious bombardment ensued as a result in the hours leading up to the armistice coming into effect there was little reduction in the rate of death.

For some reason the Americans now launched a series of assaults on towns that in just a few hours’ time would be given up without a fight. Such reckless action was to result in 3,500 unnecessary American casualties and a Congressional Inquiry.

The last British soldier to be killed of the 564,517 who died on the Western Front was Private George Edwin Ellison, aged 40. He had previously been a professional soldier but had left the army in 1912 to marry and raise a family. He had been working as a coal miner in Yorkshire when he was recalled to the colours in 1914. He was shot dead at 09.30 as he scouted positions just outside Mons.

The last French soldier to be killed of the 1.3 million who died on the Western Front was Private Augustin Trebuchon, aged 40. He had been working as a shepherd when he volunteered to serve in the French Army. He was shot dead at 10.45 as he was on his way to inform his fellow soldiers that soup would be served as soon as the Armistice came into effect. He had enlisted on the first day of the war and had died on its last.

The last Canadian soldier to be killed of the 56,639 who died on the Western Front was Private George Lawrence Price, aged 25. He had been conscripted into the army in October 1917 but was nevertheless an enthusiastic soldier.

On the last day of the war his Unit pursued some Germans into a house near the town of Mons, but they managed to escape. Despite being advised to remain inside the house until the Armistice came into effect he chose to do otherwise. As he exited the house at 10.58 am he was shot dead by a sniper.

The last American soldier to be killed of the 53,402 who died on the Western Front was, Private Henry Gunther, aged 23. He was drafted into the army in September 1917, where his previous employment as a bookkeeper saw him promoted to Sergeant and assigned to Army Stores. A letter home seen by the Censor in which he criticised the appalling conditions in France saw him demoted back to Private, however.

He was shot dead at 10.59 am when he inexplicably charged some nearby Germans, though it has been suggested that he was taking this last opportunity to restore his reputation and recover his old rank. The Germans had shouted to him, waved their arms and tried to usher him away but when he opened fire they had little choice but to respond in kind. The luckless American with the German name whose grandparents had come from the old country died less than 30 seconds before the Armistice was due to come into effect. It made him the last official casualty of the Great War.

The last German soldier of the 1.7 million who died on the Western Front was Lieutenant Alfred Tomas who was shot dead at 11.01 when he approached some American soldiers to inform them that his men were preparing to vacate their positions. The Americans had not been told of the ceasefire.

There were 10,944 casualties on the final day of the war of whom, 2,738 were killed but the total number of those who succumbed to wounds received in the days, weeks and months following the ceasefire was almost 68,000.

At 11.00 am precisely the guns ceased firing and an eerie silence descended upon the Western Front. The smell of cordite and the stench of rotting corpses remained but the din of war had ceased. The constant fear of death that had been so much a part of their daily lives was no more. Now there was nothing, just silence and a bloody great mess. Any celebrations were somewhat muted with soldiers simply milling about not knowing what to do or taking the opportunity to sleep. There was disbelief of course it being so unexpected even, so it was a sense of relief that prevailed not triumphalism. But this was not echoed on the Home Front.

In Paris gas lamps were lit for the first time in four years as tens of thousands gathered in the centre of the city and chanted for the Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau.

In London, the British Prime Minister, David Lloyd George was angry. He had wanted the ceasefire to begin at 2 pm when he was due to address the House of Commons and could make the announcement himself but by the time, he rose to do so the news was already out and the moment for theatre had passed.

Big Ben had also tolled for the first time since the start of the war as crowds flocked to Trafalgar Square amid scenes of wild jubilation and lewd behaviour unknown in previously tight-laced Edwardian Britain.

Similar scenes were witnessed in Times Square New York and throughout the towns and cities of all the victorious Allied powers. But the mood was to become more sombre in the coming days as the true toll of four years of unparalleled bloodshed began to sink in.

In Germany there was a sense of stunned disbelief. Despite the overwhelming desire for peace many people could not understand the capitulation when their army still fought everywhere on foreign soil.

In time the returning troops were to be blamed for what had happened and would be shunned sometimes even abused in the streets. A little-known Corporal Adolf Hitler, who was recovering in a Field Hospital from temporary blindness caused by a Mustard Gas attack wept when he heard the news of the armistice. But his emotional response did not reflect the general mood which regardless of the shame and humiliation that accompanied defeat the sense of relief at the wars end was palpable.

Few could have imagined at that moment that the ‘War to End all Wars’ had merely been the dress rehearsal for an even more catastrophic conflagration to come.

Share this post: