Young Adolf: The Adolescent Hitler and Beyond

Posted on 10th February 2021

“To know Hitler, means to know him before he came to power.”

(Otto Strasser)

Adolf Hitler was born in Braunau-Am-Inn on 20 April 1889, a subject of the then Austro-Hungarian Empire. His elderly father, Alois Schickelgruber was a Civil Servant, and an illegitimate child most probably the issue of a liaison between his mother, a housekeeper, and the nineteen-year-old son of her Jewish employer, Leopold Frankenberger who continued to pay maintenance for the child long after she had left his employ.

In 1876, Alois applied to change his surname by deed poll to that of his stepfather Johann Georg Hiedler. On the deed poll document the name was written down incorrectly as Hitler, which he apparently quite liked. The likelihood is that he had been pressurised into changing his surname by the Schicklegruber family who did not want knowledge of his illegitimacy to stain the family name. It has been suggested that he was also paid to do so.

Alois, an ill-tempered and some might say unsympathetic man was employed as a minor customs official, a job he took very seriously and great pride in. He was rarely seen out of uniform and liked to be addressed formally with reference to his rank. In 1873, he married Anna Glasl-Horer, an independently wealthy but sickly woman. It was hardly a love-match and Alois was to have numerous affairs including fathering a child, also named Alois, by their nineteen-year-old maid, Franziscka Matzelsberger who was soon after ordered to leave the household. In 1876, he invited his seventeen-year-old niece Klara Polzl to be their housekeeper and to take care of Anna.

Alois and Anna were forbidden from divorcing by the Catholic Church but had been living separate lives for many years before she died in April 1883 leaving him free to marry Franziscka with whom he was to have another child they named Angela, before she too died just over a year later of lung disease. Not long after On 7 January, 1885, at the age of forty eight, Alois married yet again, this time to his cousin Klara Polzl, half his age.

As his niece, Alois had to get special dispensation from the Catholic Church to marry Klara which was granted on humanitarian grounds though it was in effect a fait-accompli as Klara was already pregnant with his child.

On the day of their wedding Alois wore his uniform, held a short reception for a few friends and then returned to work. It was an early insight into the kind of man Klara had married and even she expressed shock at his behaviour; but then there were to be few terms of endearment and even less moments of affection ever exchanged between them. Indeed, Klara did not even refer to her husband by name but as uncle.

Klara was to have six children by Alois the first three of whom were to die before on 20 April 1889, she gave birth to a son they named, Adolf. He was to be her first healthy child and she adored him showering all her love and affection upon him but as the young Addy, as he soon became known grew up, he was to have a far more fractious relationship with his father.

Addy had dreams of becoming an artist something his father thought ridiculous and would not countenance. He expected him to follow in his footsteps as a Civil Servant, but the young Adolf had no intention of wasting his life in the application of other people’s petty rules. They rowed often and Klara would always take her son’s side even when he deliberately provoked his father. His younger sister Paula was to write that: “Adolf challenged my father to extreme harshness and got his sound thrashing every day.”

It was as if his father’s wrath was his validation, and it seems the bullying was handed down for Paula also tells of how after a beating her brother would often slap her face if she dared disagree with him.

Adolf may have been the fulcrum of an old man’s ire, but Alois regularly beat all his children and they were relieved when following his retirement he spent his days tending to his bees and his nights at the local tavern. When on 3 January 1903, he died of a stroke the period of mourning was brief and though Adolf did shed a tear for his father his death for him was a release. Now he would have his way.

As a child Adolf attended a local monastery where he sang in the choir and was praised for having a fine voice. He also attended Church regularly and later admitted that he found Latin Mass intoxicating and that Catholic ceremony had made a lasting impression on him.

His favourite game was Cowboys and Indians which he would play with his friends and always insisted upon being the leader of the Indians. He had always been a voracious reader though he would not waste his time on books he thought he might disagree with for he could not tolerate views that were diametrically opposed to his own. He was a great admirer of Jonathan Swift, in particular the books Robinson Crusoe and Gulliver’s Travels but his favourite author was always the low-brow Karl May, who wrote dime novel westerns.

Later in life he would indulge his passion for the movies sharing with his fellow dictator Josef Stalin, a love of light comedies and musicals.

In 1896, Klara gave birth to a baby boy she named Edmund.

Adolf adored his younger brother and when he died on 2 February 1902, he was utterly devastated and people remarked upon how greatly it had affected him; but then he was always greatly disturbed by death, particularly the death of those close to him. He did not like to witness it and he always feared emotional pain more than he ever did physical injury, and as the Holocaust he had engineered continued apace he refused mention of it in his presence, or for it to be referred to in any correspondence. He didn’t wish to be associated with the horrors that were being committed in his name no doubt, but to believe this was solely to appear an innocent bystander to events is not to understand the man.

Adolf, whose bedroom overlooked the grave of his younger brother, was sullen and depressed following his death, and he could often be found sitting alone by his grave quite late into the night just staring up at the stars. His depression wasn’t lifted until the death of his father which created a release that he had previously thought unimaginable. He would now be able to be the great artist he undoubtedly thought he was.

He soon lost all interest in school considering his teachers fools and not worthy of his attention, and the only class he bothered to attend was history taught by Leopold Potsch who imbued him with stories of German heroes and the destiny of the German people.

In 1905, he left school without passing his final exams informing his mother that he was leaving home to go and live in Linz, a place that to the young Adolf seemed the centre of the world. Klara was distraught at his leaving but would not oppose her beloved Addy’s wishes and so he left home aged just sixteen, with his mother’s blessing.

In Linz, he lived off the generosity of his mother who regularly sent him money and food parcels which allowed him to do as he pleased wandering the streets sketch pad in hand visiting the city’s museums and reading libraries. With time to dream he developed grandiose schemes for the architectural redevelopment of the city which he still hoped to see implemented even at the end of his life. It was also while in Linz that he met the only man he would ever call a friend, the aspiring musician, Auguste Kubizek.

In 1907, he applied to enrol at the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts but failed the entrance exam. Still, encouraged by his mother he remained undeterred, but Klara was by this time seriously ill with breast cancer and by the winter of 1907, her condition had worsened to such an extent that her death appeared likely.

Hitler returned home to care for his mother doing the cooking and tending to the household chores but was soon informed by the family’s Jewish doctor Eduard Bloch that there was no prospect that Klara would recover. He would later say referencing Hitler’s relationship with his mother that he had had never witnessed a closer attachment or seen anyone so sad. A distraught Adolf later admitted that it was the only time he had ever prayed. But his prayers would go unanswered and on 21 December 1907, Klara Hitler, died, aged 47. Adolf was inconsolable for some weeks weeping profusely at her funeral and again many times thereafter – it was to be the worst moment of his life.

Visiting Dr Bloch to pay the medical bill he told him “I shall be grateful to you forever” and he was to prove as good as his word. Following the Anschluss with Austria in 1938 and the subsequent persecution of the Jewish community Hitler ordered that the Bloch family be left alone, and they were later permitted to leave for the United States taking their property and personal fortune with them.

In February 1908, Hitler went to live in Vienna where he hoped to at last fulfil his ambition to be an artist.

Vienna was a very different city to Linz being the centre of a multi-ethnic Empire with a large Jewish population and where ethnic Germans were in a minority. Adolf was initially shocked by what he found and later wrote in Mein Kampf about when he first became an anti-Semite:

“Once I was strolling through the inner-city when I suddenly encountered an apparition in a black kaftan with long black hair locks. Is this a Jew was my first thought. For, to be sure, they had not looked like that in Linz. I observed the man furtively and cautiously, but the longer I stared at his foreign face, scrutinising every feature, the more my question assumed a new form, is this a German? The more I saw, the more sharply they became distinguished in my eyes from the rest of humanity.”

His friend Kubizek would later contradict this stating that Hitler was already a convinced anti-Semite when they had been together in Linz, but his comments make sense in respect of Vienna being a hotbed of anti-Semitism. Its popular Mayor Karl Lueger had based his electoral campaigns upon anti-Jewish rhetoric even though, in a population of 2,031,420 only 175,294 were classified as Jews. However, their representation among the professional classes was disproportionate to their overall number. For example, 75% of Viennese bankers were Jewish, 63% of artists and academics were Jewish, 51% of doctors, and 49% of lawyers. This caused a great deal of resentment, but it was too easily forgotten that the majority of those who lived in the Jewish Leopoldstadt district of Vienna were unemployed and homeless. This was the world that the young Adolf Hitler now lived in, but for all the bitterness and hatred he later expressed towards the city his time in Vienna defined his life.

People who knew him around this time remember a quiet, reserved, and polite, if slightly odd young man who women found attractive though he rarely showed any interest in them. Instead, he always had his head in some book, magazine, or other roaming the streets of the city dressed as he thought an artist would, visiting galleries, museums, and attending musical recitals. His nights he spent at the opera, dreaming dreams of what would be.

A few weeks after Hitler had established his home in the city his friend Kubizek arrived, and Hitler went to meet him at the Station. In his memoir of their friendship Kubizek recalls how a clearly delighted Hitler took his hand and kissed him full on the lips leading some to suggest that their relationship was deeper than at first thought but he does not elaborate further and little evidence exists this may have been the case.

Kubizek later described that wearing his best dark overcoat, a broad-brimmed felt hat and carrying an ivory handled cane the slim, pale-skinned Hitler looked every inch the gentleman and together they strolled to his new apartment on the Stumpe Gasse.

Of their life together Kubizek explained how Hitler would sleep until noon and always stay up late into the night. He would be willing to discuss his views on any topic to anyone who showed an interest in listening and was always brimming with ideas talking excitedly of projects he had in mind but despite the earnestness with which he spoke his behaviour would be mostly temperate and polite unless anyone dared to contradict him or doubt the absolute truth of what he was saying. Then he would shout and rave and refuse to listen. He was to describe him unstable but even so, Hitler and Kubizek enjoyed each other’s company, though their relationship soured somewhat when Kubizek was accepted into the Vienna Academy of Music where Hitler’s application to the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts was once again rejected. Indeed, this time he wasn’t even permitted to sit the entrance exam. He was jealous of his friend, but this soon passed, at least Kubizek thought it had but while he was away doing his National Service, Hitler moved out of their shared apartment without telling him he had done so or leaving any forwarding address.

Auguste Kubizek was to continue to follow his friend’s career with interest though he did not attempt to contact him again for another twenty-five years when he wrote to Hitler to congratulate him on becoming German Chancellor. To his great surprise he wrote back declaring: “I should be very glad to revive again once more with you those memories of the best years of my life.” They were reunited on 9 April 1938, when they chatted for more than an hour and Hitler offered to fulfil Kubizek’s dream of becoming the conductor of an orchestra, an offer he politely declined. So instead, Hitler insisted upon paying for his children’s education. They were to meet again on two further occasions, the last in 1944 when he was to send Kubizek’s mother a basket of food on the occasion of her 80th birthday.

Interestingly in 1940, Hitler had told Kubizek: “This war will set us back many years. It is a tragedy. I did not become the Chancellor of the Greater German Reich to wage wars.”

Asked to write an account of their time together Kubizek recalled the story of how Adolf Hitler had fallen in love with a mutual friend of theirs, a young woman named Stefanie, and how he would write poetry and love letters to her but never had the courage to send them. Later told of this fact the woman concerned feinted with astonishment.

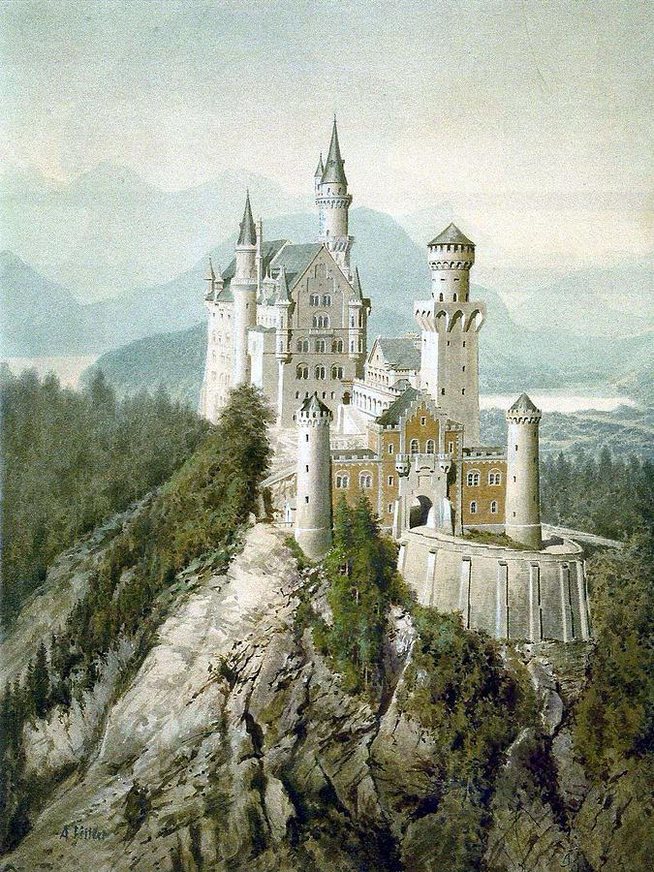

For much of his time in Vienna, Hitler lived off the proceeds of a small inheritance. He also sold drawings he had made of the local architecture and landscape some of which he had printed as postcards to sell in local shops and to tourists. He never sought regular employment and instead spent his days immersed in the works of Hegel, Nietzsche, and the anti-Semitic writings of the Englishman Houston Stewart Chamberlain. He also loved the Operas of Wagner and his stories of the Nordic Gods and was to spend much of his life thereafter trying to make them a reality with all that entailed.

By the end of 1909 however, his inheritance had run out and he found himself both penniless and homeless. He was to all intents and purposes an inconsequential drifter. Yet few who met him during this period ever seem to have forgotten the experience.

In early 1910, he entered a Homeless Shelter on the Meldemenstrasse that was mostly populated by poor Jews and was eating at soup kitchens. By this time, he had pawned all his belongings and seen shivering one cold night he was provided with an overcoat by an elderly Jew. Still, he continued to draw and another of the residents at the Shelter, Reinhard Hanish, agreed to act as his agent hawking his art to mostly Jewish owned shops. Hanish, remembered Hitler as being emotionally unstable and prone to rages. They were eventually to fall out when Hitler accused Hanish of selling his art and pocketing the money for himself. He went to the police and in the ensuing Court Case Hanish was sentenced to eight days in prison. Twenty-eight years later in 1938, Hitler ordered Hanish’s execution for going public about their relationship.

Following his fall out with Hanish, Hitler befriended a Jew, Josef Neumann, who continued to sell his art to local Jewish retailers to cover their wall space. This was a tough time for Hitler when he was frequently cold and hungry, but he later said of the experience: “During that period I grew hard and am still capable of being hard.”

Such were Hitler’s reduced circumstances that even he was forced to work, and he did two days shovelling snow and the odd day here and there carrying bags at Vienna Station. In May 1913, he fled Austria for Bavaria to avoid conscription into the army of the multi-ethnic Empire he had now come to despise. In Munich he continued to sell his drawings. When he was asked how he expected to survive for any amount of time without regular employment he replied that it did not matter as war would come soon.

He was right and on 1 August 1914, he joined an enthusiastic crowd crammed into the centre of Munich to celebrate the proclamation of war. Upon hearing of the news, he later said that he fell to his knees and thanked heaven. Two days later he enlisted in a Bavarian Infantry Regiment.

Despite a natural desire on our parts to wish otherwise, Hitler had a good war serving as a runner carrying communications between command posts, one of the most dangerous and unenviable of duties; he was twice decorated for bravery, receiving the Iron Cross First Class in 1918 on the recommendation of his Jewish Commanding Officer.

If Hitler was a coward, then it was of the moral not the physical kind. Undoubtedly what he had witnessed during the war affected him greatly as indeed it did all the combatants but perhaps not in the way that one might expect. He was not horrified by the slaughter but by the defeat. Germany lost the war because she did not fight hard enough, she was not willing to sacrifice enough, and because she was betrayed by those at home - communists, socialists, and of course Jews. He returned from the war even more distant and aloof than he had been before. And even more determined to succeed.

By the time the war ended on 11 November 1918, he had risen to the rank of Corporal. He may have been awarded the Iron Cross, but no subsequent promotion followed. He was recuperating from a mustard gas attack that had left him temporarily blind in a Military Field Hospital about which he wrote: “If twelve or fifteen thousand of those Jews who were corrupting the nation had been made to submit to poison gas then the millions of the sacrifices made at the Front would not have been in vain.” When he heard the news of the surrender he could not believe it, tore the bandages from his eyes and wept later claiming: “It was now I decided to enter politics.”

Adolf Hitler, the man whose choices led directly to the deaths of millions of people was a tee-total, vegetarian, non-smoker and a late riser; a lazy, ill-disciplined, impatient and often ill-tempered man. He had an insatiable desire for tea and cake but ate only sparingly. He enjoyed the company of children and loved to play with his pet dog. He enjoyed the adoration of women but had an aversion to physical contact. He peddled in death but was capable of tears. He was a man of violence, but he shrank from the sight of blood. Yet he inspired a devotion that few have ever experienced before or since.

He seems to us now with all the theatre, the flourishes and the plumage that accompanied him an almost monstrous absurdity and a by-word for evil. But was he not a child of obscurity raised of modest background and no great eccentricity with all the insecurities, and neuroses of a human being. In any study of Hitler and those like him we should remember this for it does a disservice to history to make monsters of men.

For as both his architect of choice and his confidante Albert Speer remarked:

“To say that Hitler was a madman is to make a very serious mistake.”

Tagged as: Modern

Share this post: