Zeppelin: Terror from the Sky

Posted on 19th April 2021

On the early morning of 19 January 1915 two Airships the L3 and L4 armed with 8 bombs and 25 small incendiary devices took off from Fuhlsbuttel Airfield in Germany. They had been ordered to target military and industrial sites in eastern England but to avoid London, the Kaiser being concerned it was said for the safety of his relatives.

At around 08.30 they crossed the Norfolk coastline and then separated, one headed for Kings Lynn the other for Great Yarmouth.

Once over the two coastal towns the Airships let loose their loads and in the ensuing chaos 9 people were killed and many more wounded. The attacks had taken the British people totally by surprise and were the cause of much panic. What had been a largely ineffective military operation had become a terror raid and it was to prove a foretaste of things to come.

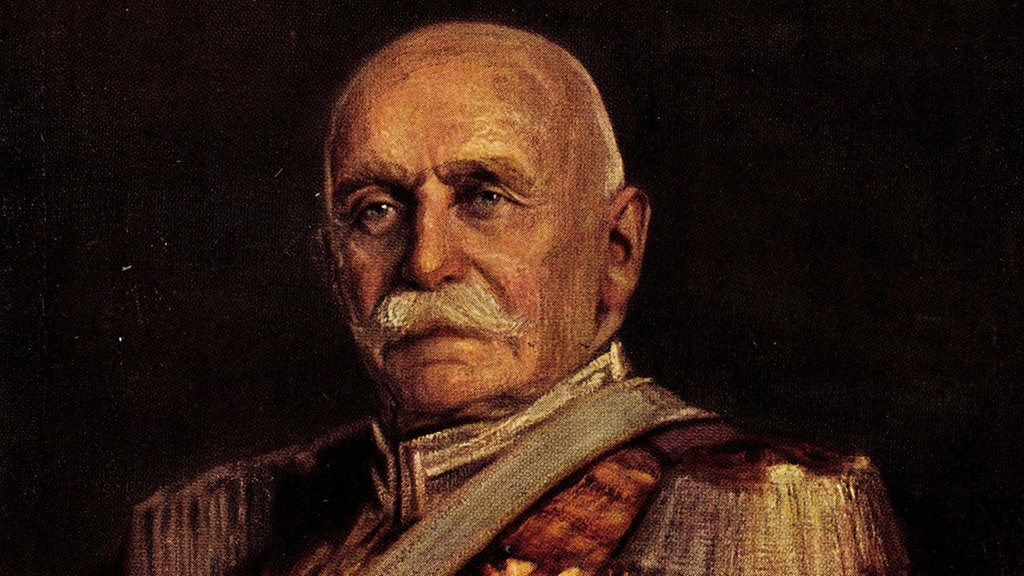

The development of an Airship originally designed for commercial travel had been the brainchild of Ferdinand Graf von Zeppelin, a German Officer who had devoted more than thirty years of his life bringing it to fruition.

The maiden flight of a Zeppelin, the L1, had taken place long before on 1 July 1900 over Lake Constance and despite its many setbacks and its huge cost, the German Military High Command were quick to recognise its potential as a weapon of war and once given the opportunity were determined to test it. Unlike its people the British Government was aware of the danger and as early as October 1914 had attempted to bomb the Zeppelin Hangars.

Following the attack on East Anglia rumours began to spread that hundreds of Zeppelins would soon appear over British cities dispensing death and destruction from the skies and that they intended to use gas bombs and had specifically targeted schools and hospitals. Despite the propaganda and the scaremongering of the press few believed that even the Beastly Hun would stoop to such levels of depravity.

On 31 May 1915 a Zeppelin attacked London for the first time and 6 people were killed in the East End.

Mobs of outraged people now took to the streets and attacked any shops with German sounding names; windows were smashed, doors kicked in, goods looted while anyone who looked as if they might be of foreign extraction was liable to a beating. The public reaction to the Zeppelin Raids was violent and ugly and out of proportion to the effectiveness of the raids themselves for the bombs dropped caused little real damage but they were also a safety valve for the expression of pent-up anger.

No targets of any military significance had been hit and in the first eighteen Zeppelin Raids only 98 people had been killed, all of them civilians. Even so, the press and the public demanded that Britain respond in kind. The Government refused stating that: "Britain should not be party to a line of conduct condemned by every right thinking man of every civilised nation."

As it stood no Zeppelin had yet been shot down and it seemed that they were able to come and go as they pleased and administer their nighttime dose of death with impunity.

Often lit up by the searchlights people were able to watch the Zeppelins as they dropped their bombs, and they could hear the few anti-aircraft guns booming out, but they could also see how ineffective they were. They were frightened and felt defenceless.

In the early hours of 7 June 1916, Lieutenant Reginald Warneford patrolling in the skies over the Belgian city of Ghent in an incident now barely remembered, encountered Zeppelin L37.

Seizing his opportunity, he was determined to attack it but his plane was armed only with bombs not machine guns but he did have a rifle in the cockpit and so flying as close as he safely could he took pot-shots but to little effect and the intensity of fire from the Zeppelin’s machine guns finally forced him to withdraw, but he had not yet given up. It took him more than two hours, but he eventually managed to fly his plane to a height of more than 13,000 ft and above the Zeppelin. He now swooped down and dropped his six bombs onto its roof. Some of the bombs missed the target, others bounced harmlessly off its shell, but then there was a tremendous explosion that was so great it almost destroyed his, own plane.

As Warneford struggled frantically to keep his plane in the air he could see the Zeppelin L37 crashing to the ground in flames. It had been utterly destroyed, incinerated, as also had those crewmen inside. For his actions that night Lieutenant Warneford was awarded the Victoria Cross, but he was never to receive it. Ten days later he was killed in a flying accident.

Reginald Warneford was the first man to down a Zeppelin but because it had happened in foreign skies it had been a feat largely ignored in Britain.

On 3 September 1916, Lt Leefe Robinson was patrolling the skies over London when he intercepted one of sixteen Zeppelins that had been sent on a mass-bombing raid of the city.

Flying at 12,000 feet with little instrumentation and in poor visibility he could see that the anti-aircraft fire was falling well short of its intended targets. Armed with recently issued new incendiary bullets that had yet to be proven in combat he attacked the first Zeppelin he encountered. His first two attacks appeared to have little impact and his plane had taken several hits but on his third assault his bullets penetrated the Airships hydrogen gas tanks and it suddenly exploded into a ball of flames and had crashed to the ground within seconds.

The dogfight had been seen by thousands of Londoners who had come onto the streets to witness the spectacle and as the Zeppelin fell to earth the crowd cheered and began to sing the National Anthem. All fifteen crewmen aboard were burned to death.

The crash site behind the Plough Inn Public House in the village of Cuffley soon became a tourist attraction with thousands of people queuing up to witness the macabre scene.

Particularly popular was the charred remains of a German crewman and people had their photograph taken standing beside it.

Leefe Robinson became an overnight national hero and was awarded the Victoria Cross, along with a large cash prize and a trophy from his hometown. In 1917 he was transferred to the Western Front where, forced to crash land he was captured by the Germans. Treated badly in captivity he was so physically weakened that he died within weeks of being repatriated back to England at the end of the war on 31 December 1918, a victim of the Spanish Flu Pandemic.

For all the terror it spread the Zeppelin was proving militarily ineffective. They were slow and cumbersome; their bomb load was limited and had now been shown to be vulnerable to attack. Many planned raids had even had to be abandoned due to bad weather.

By January 1916 the British had begun to put in place effective air defences and in London alone there were to be 490 searchlights and 271 anti-aircraft guns and similar levels of defence were replicated in all the major cities. Planes armed with ever more powerful incendiary bullets also patrolled the skies day and night.

Far more effective than the Zeppelin were the raids by the German bomber planes that they had paved the way for. On 25 May 1917 a fleet of Gotha Bombers attacked the Kent town of Folkestone killing 76 people in just 4 minutes. On 13 June they attacked London killing 97 and wounding a further 431. It was the deadliest raid of the war.

Despite their greater effectiveness planes never had the same quiet menace of the Zeppelin - the large low-flying dispenser of death casting its shadow over cities so, undisturbed as it went about its destructive and deadly business. It fascinated and horrified in equal measure, and many people were killed and injured coming onto the streets to watch it.

Many in the German High Command began to view the Zeppelin as a costly failure and the Army abandoned its use of them; the Navy however decided to persevere and on 28 September 1916 appointed Captain Peter Strasser to be its Leader of Airships.

Strasser was both single-minded and proactive and determined to prove the effectiveness of the Zeppelin as a weapon of war if not in its capacity to destroy then as a purveyor of fear. Unlike many he understood its value as a weapon of terror: “We who strike the enemy where his heart beats have been described as baby killers. But now there is no such thing as a non-combatant. Modern warfare is total warfare”.

On 5 August 1918 he organised the largest single Zeppelin raid on Britain. It would involve 24 Zeppelins and would take place at night to maximise the terror and he would lead it himself.

It was to prove a disaster and seven Zeppelins were lost including Strasser’s own which was shot down over the North Sea and all its crew killed. Strasser’s determination to prove the Zeppelin’s value had not only cost him his own life but was to see the Zeppelin effectively shelved as a weapon of war.

The Zeppelin Raids had frightened the British people who now realised they were no longer safe in their little island, but they would get used to it; and though the Zeppelin would continue to fly elsewhere its effectiveness was much diminished and at ever-increasing cost to themselves. By the end of the war 77 of the 115 Zeppelins that participated had been destroyed or disabled beyond repair.

Over Britain the Zeppelins undertook 53 strategic bombing raids on London and elsewhere during the war and of the 84 Zeppelins involved 30 were lost to accident and enemy fire. A little over 1,500 British civilians died as a result of direct military action during the Great War of which 523 were victims of the Zeppelin.

The Zeppelin made no difference to the course of the war, but it did make the British people aware of how vulnerable they now were to attack from the air. It would be a mere 23 years later and the outbreak of the Second World War before they found out just how vulnerable.

Share this post: