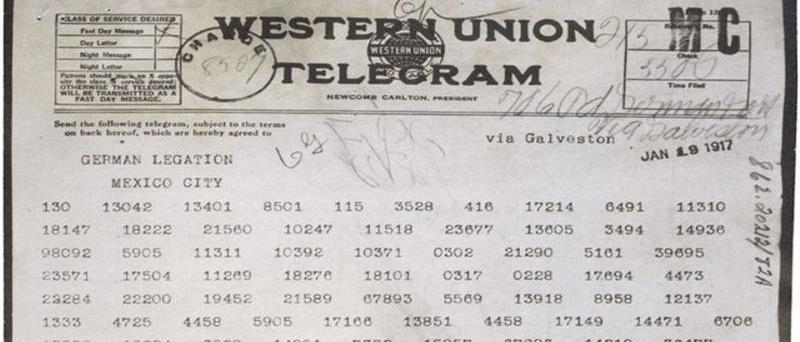

Zimmerman Telegram

Posted on 19th April 2021

In the early afternoon of 11 May 1915, as it passed by the Old Head of Kinsale off the southern coast of Ireland just within sight of land the RMS Lusitania was struck by a single torpedo fired from the German submarine U.20. A secondary internal explosion soon followed causing her to sink in just 18 minutes drowning 1,198 of the 1,962 passengers and crew aboard including 128 Americans.

The sinking of the Lusitania caused outrage around the world and particularly in the United States where it was not only a human tragedy but a propaganda coup for the British who keen to encourage the Americans to enter the war on the Allied side exploited it mercilessly.

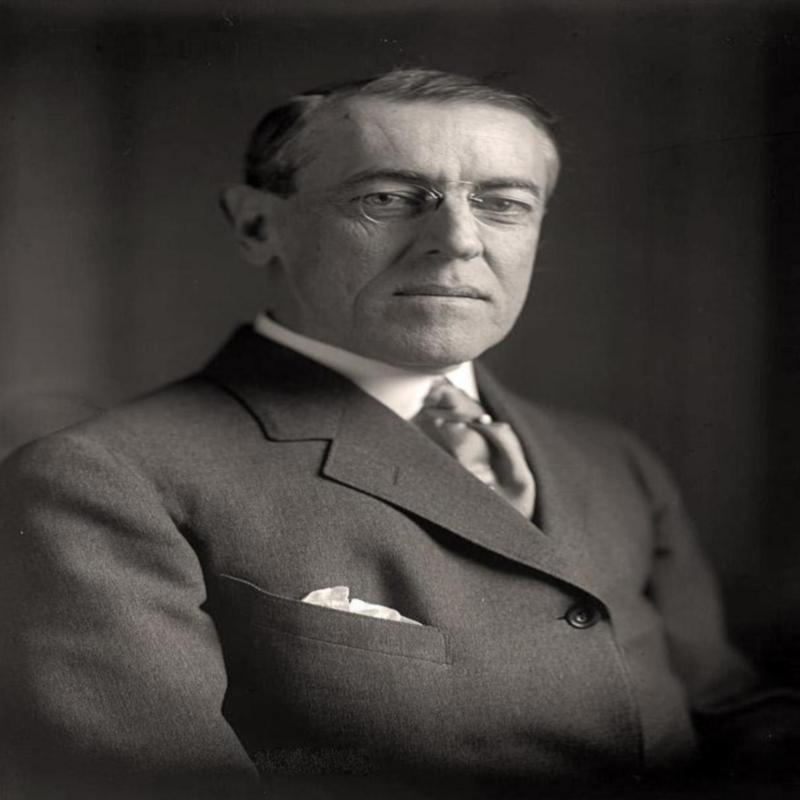

But President Woodrow Wilson was quick to end speculation that the Lusitania’s sinking would prove a casus belli when shortly after, he declared, “There is such a thing as a man being too proud to fight. There is such a thing as a nation being so right that it does not need to convince others by force that it is right.”

Many were relieved that the United States would not become embroiled in the conflict that was tearing Europe apart but to others it seemed little short of moral cowardice and the pro-war lobby with its most vocal spokesman the ex-President Theodore Roosevelt not shy in declaring so.

No sooner had the outrage over the Lusitania’s sinking begun to subside when it was revived by the German artist Karl Goetz who angry over the universal condemnation it had received and believing that it had been little more than a contraband runner produced a medallion to commemorate the event.

Its depiction of people queuing in line to buy tickets for the doomed ship from the skeletal image of death sought to highlight British responsibility for the sinking, but he had mistakenly incorporated the wrong date 5 May, two days before the sinking making it appear premeditated. It proved another propaganda coup for the Allies and the British swiftly produced 250,000 replica medallions distributing many of them in the United States.

President Wilson remained determined to keep the United States out of the war however, and despite demands from his political opponents that he act instead communicated America’s formal response and his personal disapproval of German actions in a series of vaguely worded telegrams. He was barely censorious let alone threatening but aware of the growing war lobby in America and that Wilson was due to stand for re-election the following year the Germans soon after abandoned their policy of unrestricted submarine warfare.

Despite Americans continuing to die in German U-Boat attacks it was never in great enough numbers to dictate a change of policy and Wilson’s neutrality was to prove popular with a people reluctant to become involved in foreign entanglements, so much so that the slogan for his successful re-election campaign was – He kept us out of the war.

With the war on the Western Front deadlocked and having to prop up a series of weak and increasingly unstable allies by early 1917 the German position was becoming parlous. Moreover, the Royal Navy’s blockade of German ports was slowly squeezing the life out of the country.

Indeed, the pinched and harrowed faces of the starving and the swollen bellies of abandoned children were becoming a familiar sight on the streets of German towns and cities. It was undermining morale at home and thereby threatening discipline at the front - a means had to be found to break the stalemate.

Cutting Britain’s Atlantic lifeline, it had been estimated would reduce the imported foodstuffs she needed to survive by half. She would then have to seek terms with Germany within six months of any resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare.

But to resume submarine warfare as before would almost certainly see the United States enter the war on the Allied side. The Germans, however, were willing to gamble that they could bring the British to heel and defeat an isolated France before the Americans could mobilise, train, equip and transport an Expeditionary Force large enough to affect the outcome. It was a perilous course of action, but plans were already underway to emasculate further any American response.

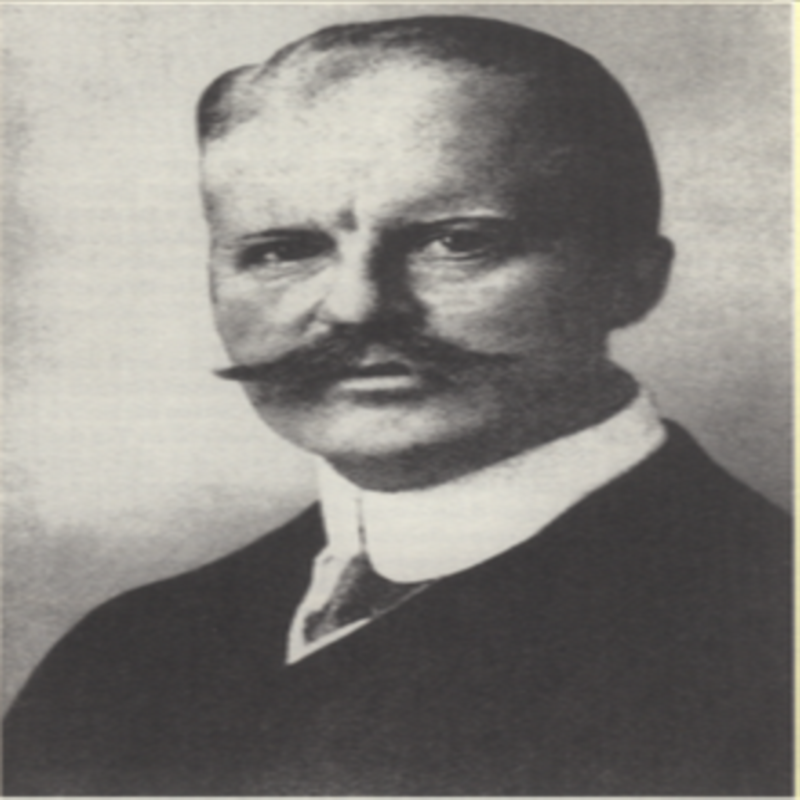

On 11 January 1917, the German Foreign Minister Count Arthur Zimmerman sent a coded telegram intended to remain secret to their Ambassador in Mexico proposing in the event of a war between the United States and Germany an alliance:

"We intend to begin on the first of February unrestricted submarine warfare. We shall endeavor in spite of this to keep the United States of America neutral. In the event of this not succeeding, we make Mexico a proposal of alliance on the following basis: make war together, make peace together, generous financial support and an understanding on our part that Mexico is to reconquer the lost territory in Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona. The settlement in detail is left to you. You will inform the President of the above most secretly as soon as the outbreak of war with the United States of America is certain and add the suggestion that he should, on his own initiative, invite Japan to immediate adherence and at the same time mediate between Japan and ourselves. Please call the President's attention to the fact that the ruthless employment of our submarines now offers the prospect of compelling England in a few months to make peace." Signed, ZIMMERMANN

But it was far from a secret.

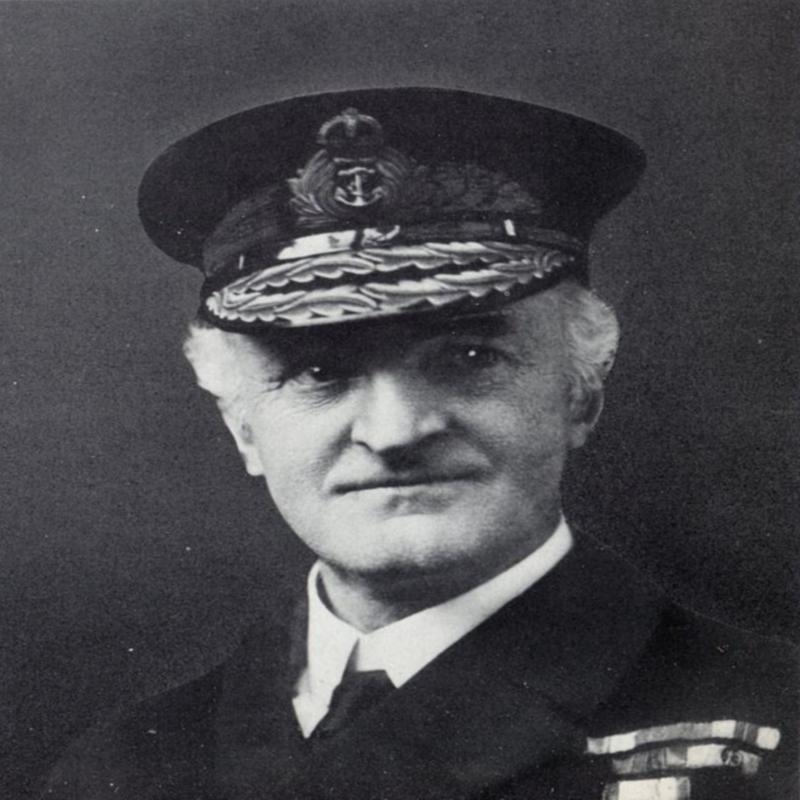

The German trans-Atlantic telegraph cables had been cut in the early days of the war and they had since been using the American cables. But unknown to them and indeed the United States, the British had long been intercepting American cable traffic. They had also since August 1914, when the Russians had recovered the codebook from the stricken Cruiser Magdeburg and passed in onto their ally been able to break the German codes. The intercepted cable was sent to the codebreakers based in Room 40 of the Admiralty building in London. They soon realised they had received a diplomatic bombshell but one that had to be handled with care.

It would not only be reason for embarrassment but a potential cause of friction if the Americans discovered that British Intelligence had been reading their diplomatic cables and to reveal the contents of the telegram would also expose the fact they had broken the German codes.

They knew they had in their possession the information that would make it very difficult for the United States to remain neutral but Admiral Reginald ‘Blinker’ Hall, in command of Room 40 advised caution - because of the potential fall-out from its revelation it must remain secret until the moment of maximum impact. In the meantime, they would do their best to muddy the waters and disguise their sources.

The Mexican Government had not responded to the Zimmerman Telegram, but its de-facto President Venustiano Carranzo did not dismiss it out of hand, the feasibility study he established to look into it did.

Mexico, still amid a revolution was in no position to wage war on its more powerful neighbour and as there was little chance that the Germans could provide any effective assistance there was no prospect of re-conquering its lost territories. Even so, Mexico was not to formally reject the German proposals until after the United States entry into the war.

Despite the Mexican Governments silence on 1 February 1917, Germany declared that it was resuming unrestricted submarine warfare.

This was the moment ‘Blinker’ Hall had been waiting for, but he did not pass on the decoded telegram to the Foreign Office to present to the American Ambassador until 25 February providing time for the German U-Boats to have an impact.

The Zimmerman Telegram caused an outcry in America that changed public opinion at a stroke. Theodore Roosevelt in typically robust fashion stated in reference to Woodrow Wilson – if he doesn’t go to war now, I shall skin him alive. He needn’t have worried for unlike the sinking of the Lusitania the Zimmerman Telegram was an act of aggression that posed a direct threat to American security.

On 2 April, President Wilson outlined the case for war to a joint meeting of Congress declaring that right was more precious than peace and that America would save the world for democracy. Congress was to vote almost unanimously for war and four days later on 6 April it was formally declared.

The Zimmerman Telegram must be considered as one of the greatest diplomatic blunders in history. It had forced a reluctant President to go to war, it rallied a people many of whom had been hostile to the Allied cause behind their country, and it produced an enemy whose capacity to wage war was far greater than all the other combatants combined.

The resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare was also a strategic blunder for it was the precursor to the adoption of the convoy system and the protection it now afforded to merchant shipping against U-Boat attack meant there was little prospect of bringing Britain to its knees by submarine warfare alone, unrestricted or otherwise.

Tagged as: Modern

Share this post: