Battle of Hastings

Posted on 10th January 2021

Following the death of Edward, the Confessor in January 1066, Harold Godwinson was crowned King of England, however others had claim to the throne and they would fight for it.

First to invade was Tostig, Harold Godwinson’s brother, along with Harald Hardrada of Norway, but they were defeated by Godwinson at the Battle of Stamford Bridge in Yorkshire.

This left only William Duke of Normandy to contend with. William decided not to invade immediately but to spend many months building his army in France.

He finally set sail from France on 27 September and landed at Pevensey, Sussex on the south coast of England on the morning of 28 September 1066. On landing, William received the news of Harold’s victory against his Norwegian invaders. Harold was already marching his army south in preparation of Williams invasion.

Harold rested his army in London for a few days, then continued marching south to meet Williams army, and meet them he did on 14 October 1066 at the Battle of Hastings. The battle itself, actually took place seven miles outside of Hastings in the town of Battle.

Harold positioned his army high on Senlac Hill overlooking the battlefield. His soldiers were weary after their battle in Yorkshire and the subsequent march south.

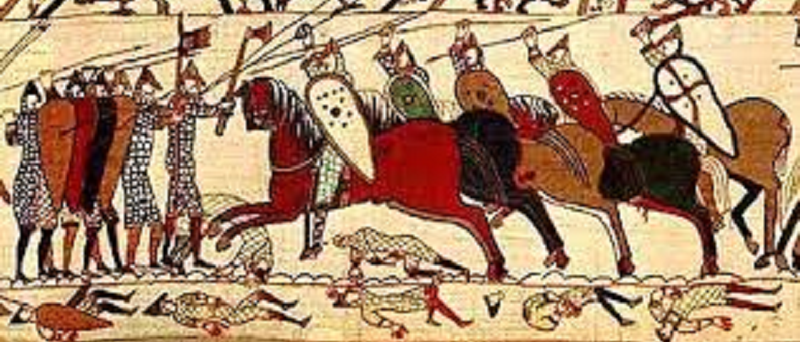

Harold’s army was heavily outnumbered and had no choice but to fight a defensive battle. He set his front soldiers in a shield wall formation (holding shields close together or overlapping to form a wall of protection) and prepared for the onslaught.

William formed his army into three sections with archers at the front and foot soldiers behind. William sent his archers uphill, to shoot at the English shield wall, but this made little impact. He then sent his spearmen forward, but again they failed to impact on the shield wall. Williams army, attacking uphill were unable to gain any force of attack. Cavalry were then sent, but the English shield wall continued to hold firm.

Rumours circulated amongst the Norman army that their leader William was dead; this caused them to retreat. Many of Harold’s Saxon army followed the Norman knights downhill; William seeing this removed his helmet to show his soldiers he was still alive, then turned back to lead a counter-attack charging at Harold’s men, who were no match for William’s mounted knights.

The shield wall continued to hold, but was becoming weaker. William charged the Saxon army again and again. As the shield wall weakened, William sent both his cavalry and foot soldiers to attack together. At the same time his archers fired arrows high into the air, both to distract the opposition and to fly over the shields and land on top of the English.

The shield wall having held strong, now began to crack and break. Hand to hand combat ensued for hours with the English finally being massacred.

Harold died in the battle, hit in the eye by an arrow; his army now without its leader started to flee.

By nightfall the battle was over, the English either dead or being pursued by William’s men through the surrounding area.

Harold was always going to be at a disadvantage, his army were weary from battle in Yorkshire and the long march down south. William was an experienced military leader and his cavalry contingent also vastly outnumbered that of Harold giving him greater flexibility in battle.

The day after the battle Harold’s body was identified and his personal standard was handed to William. The King of England had been defeated, but still the English leaders opposed William.

William rested his army for five days and then marched towards London. He continued to meet opposition on his march to London including at Winchester, Canterbury and then at Southwark and Wallingford. Being unable to storm London Bridge, he had to take a longer route to London.

English leaders finally surrendered to William at Berkhamsted in Hertfordshire. William finally received what he believed to be his. He was crowned King William I of England on 25 December 1066 at Westminster Abbey. He continued to meet opposition to his crown for many years to come.

He later became known as ‘William the Conqueror’.

Tagged as: Junior Middle Ages

Share this post: