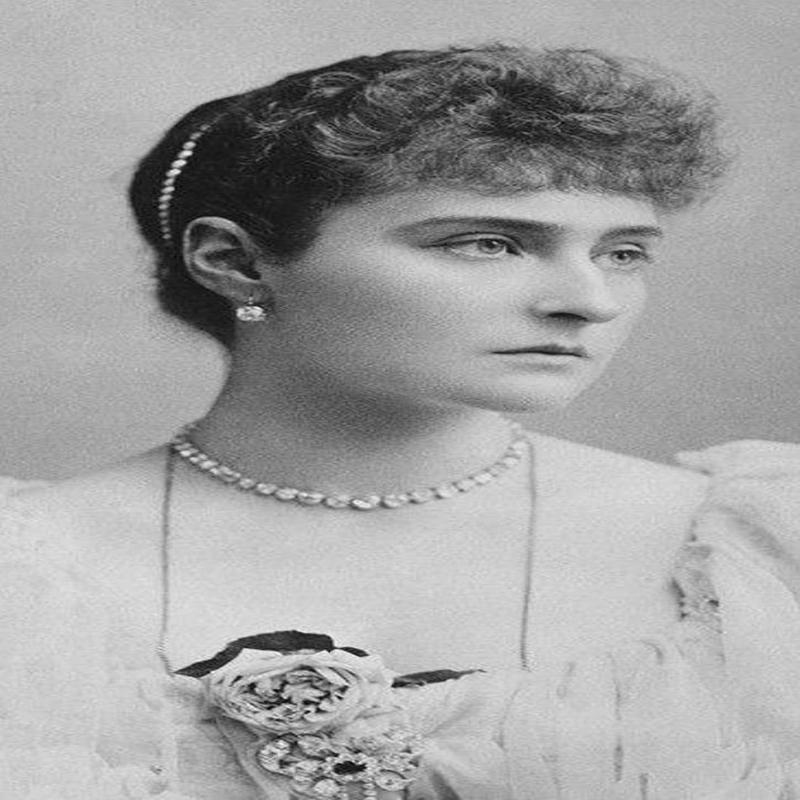

Alexandra Feodorovna: The Last Tsarina

Posted on 17th March 2021

She was the favourite granddaughter of Queen Victoria and was to marry into one of the great Dynasty’s of Europe – the Romanov’s. As the descendants of both Peter and Catherine the Great they were the absolute rulers of the vast Russian Empire and had been so for more than 300 years.

As wife to the Tsarevich Nicholas she would one day become Empress, but little could she have imagined that she would be its last and that little more than twenty years later along with her husband and children she would be taken to a dank and dimly lit cellar and be shot to death by those she had so recently ruled.

She was born on 6 June 1872, in Darmstadt, Germany, as Princess Victoria Alix Helena Louise Beatrice, known simply as Alix of Hesse. As a child she frequently used to holiday in England with Queen Victoria and her family with whom she was popular and was to be remembered fondly for her always ready smile and sunny disposition, a trait that few would recognise in later life.

Indeed, so popular was she that Queen Victoria wanted her to marry her grandson Prince Albert Victor, but this Alix flatly refused to do displaying as a young woman the stubborn streak that was to characterise so much of her later life. By doing so she became one of the few people willing to stand up to the elderly Queen which Victoria actually, quite admired.

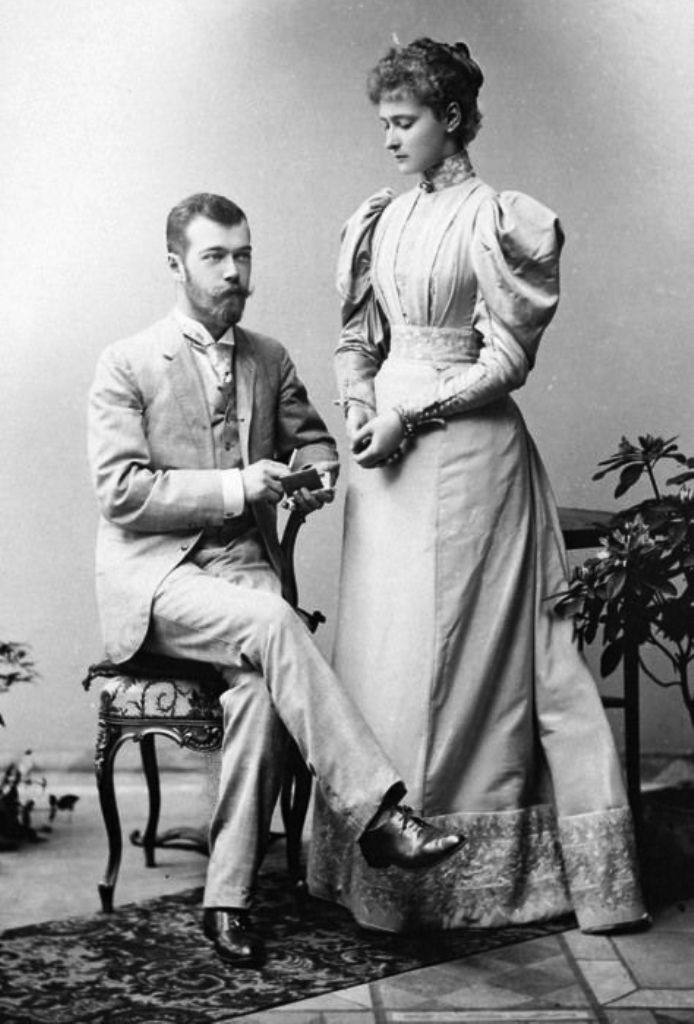

There was a reason for her refusal however, she had already met and fallen in love with her second cousin, the heir to the Russian Throne, the Grand Duke Nicholas. The feelings were mutual as Nicholas confided to his diary: “It is my dream one to marry Alix H. I have loved her for a long time.”

Much to his satisfaction he was to discover his feelings reciprocated and the six weeks Alix and he were to spend in St Petersburg together in 1889 were to be some of the happiest of his life.

Nicholas had expressed his feelings for Alix and his desire to marry her to his father Tsar Alexander III who was not keen on the match. He was avowedly anti-German, and she was also a Lutheran by faith and not of the Russian Orthodox Church which would not be accepted by the people. She would at the very least have to renounce her faith and this was something that the deeply religious Alix had shown a reluctance to do; but such was her love for Nicholas and her firm belief that it was their destiny to be together that she was persuaded to do so, there was after all only one God, and she was to embrace the Russian Orthodox faith with such commitment and zeal that it not only appeared insincere but became almost embarrassing.

Despite Alix’s best efforts to ingratiate herself with her prospective father-in-law Alexander remained reluctant to give permission for his son to marry and Alix and Nicholas were not to become engaged until the elderly Tsar had already taken to his sick bed, and they were not finally to wed until three months after his death on 26 November 1894.

Perhaps Alexander had been wise to withhold his consent for the marriage was not well received by the Russian people who said that she had come to them in the wake of a coffin.

During the celebrations for their formal Coronation eighteen months later on 14 May 1896, 1,389 people were crushed and trampled to death at Khodynka Field in Moscow. The tragedy was seen as an ill-omen for the reign to come.

The decision by the Tsar, despite his own reservations, to attend the French Ambassador’s Ball given in his honour that same night was also to prove a public relations disaster. His apparent indifference to the suffering of his people it was rumoured was because he was under the spell of a malevolent spirit and even in polite circles the new Tsarina was being referred to as – That German Woman.

The Russian people never came to love their German Tsarina despite her attempts, initially at least, to win them over. She changed her name to the Russian sounding Alexandra Feoderovna to disguise her German ancestry and embraced the Russian Orthodox Church in public displays of overt devotion. That she didn’t succeed was as much to with her character as any lack of desire on her part.

Her demeanour was haughty and cold and she was often curt to people in public and visibly uncomfortable in the presence of ordinary Russians. She chose to isolate herself from the aristocracy, including many of the Tsar’s own family who she believed were against her and her life was to revolve around her husband, a few select friends, and her religious devotions. She was lonely from the outset and her isolation would only worsen as the years passed. She was described by the historian Barbara W Tuchman in her seminal work about the First World War, The Guns of August, as being: “Beautiful, hysterical and morbidly suspicious, she hated everyone but her immediate family and a series of fanatic or lunatic charlatans who offered comfort to her desperate soul.”

As time went on she became increasingly reluctant to be seen in public or to carry out official functions. On the rare occasion that Nicholas tried to impose his will regarding such matters she would have a headache or feign illness and take to her bed. Their relationship however remained a passionate one and Alexandra gave birth to their first child, a daughter they named Olga, on 15 November 1895. She was quickly followed by three further daughters – Tatiana on 10 June 1897, Maria on 26 June 1899, and Anastasia on 18 June 1901. But still there was no son and heir and each formal notification of a Royal birth was not greeted with joy but trepidation, this woman it seemed was cursed.

When on 12 August 1904, she at last gave birth to a boy they named Alexei Nikolaevich it was met with relief rather than jubilation. Even this sense of relief would have been tempered however, had they known the truth of his condition. Alexei had been born with haemophilia, an incurable and life threatening disease that prevents the blood from clotting leading to extensive internal and external bleeding depending on the severity of the injury. As it is passed down through the female line and was known to exist in the family of Queen Victoria it could only have been inherited from Alexandra.

With the Tsarina widely believed to be cursed and with the future stability of the regime at stake it was vital that the vulnerability of the young Tsarevich be kept secret and not made public but if it was a secret then it was to prove a poorly kept one.

Alexandra was happy to surround herself with the few friends she had who shared her obsession with religious mysticism and they invariably came from the lunatic fringe of Russian upper-class society. Her closest confidante was one of her ladies-in-waiting Anna Vyrubova who was described by the foppish transvestite homosexual who would later be the man behind the murder of Rasputin, Prince Felix Yusupov, as being tall and stout with a puffy, shiny face, and no charm whatsoever.

Though she was not considered at all intelligent Anna Vyrubova was crafty and sly if obviously so, and few could have foreseen that this unattractive woman who alienated most people upon their first meeting with her would one day become the intimate friend of the Tsarina able to introduce her to any number of healers, mediums, mystics, outright charlatans and various other religious cranks.

The health of the Tsarevich was a constant concern to Alexandra and she would express her anxieties to Anna Vyrubova who along with the Militsa sisters, two Montenegrin Princesses who were heavily into the occult and held séances which Alexandra would regularly attend, told her of a Siberian Holy Man named Rasputin who had extraordinary powers of healing. Alexandra was intrigued but for the time being at least she put the information to one side.

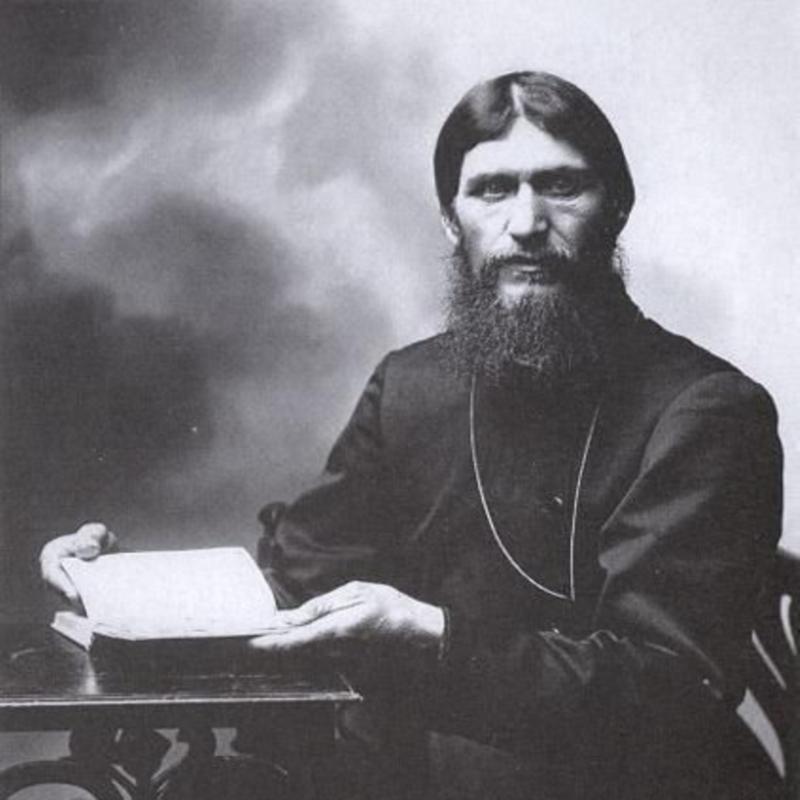

Rasputin had arrived in St Petersburg in 1903 and had since been introduced to Bishop Hermogen by the monk Illiodor who had been made aware of his reputation as a great healer and of his apparent powers of hypnosis.

Illiodor complained upon meeting Rasputinof his lack of hygiene and the suffocating stench of his body odour, accusing him of smelling like a goat. Complaints that Bishop Hermogen dismissed – a Holy Man has no need of perfumes and fancy clothes. It was a sign of his simplicity and his closeness to God and he too suggested the Tsarina provide him an audience.

The Tsarina was intrigued by all the talk and in November 1905, Rasputin was invited to dine at the Imperial Palace. He did not make a particularly favourable impression. He was scruffy and unwashed, had no table manners, had to be told not to eat with his fingers, drank to excess, and his conversation was coarse and vulgar. The Tsarina saw this as a sign that he was a simple man of faith for whom social mores were an irrelevance. The Tsar, perhaps less forgiving, merely noted in his diary: “November 1, 1905, at a private dinner made the acquaintance of a Holy Man named Grigori.”

In the late autumn of 1907, the Tsarevich fell seriously ill, and the doctors were unable to do anything to reduce his fever, alleviate his pain, or more importantly stop the bleeding. Alexandra was distraught and believing her son would die in her desperation ordered that this Holy Man, this Rasputin, be sent for immediately. Even before the request could be relayed to him Rasputin was at the Gates of the Imperial Palace. He was only admitted on the insistence of the Tsarina. The doctors objected to his presence and demanded that this Witch Doctor be forced to leave. The Tsar likewise was sceptical, but Alexandra was insistent that he be permitted to treat her son.

Rasputin immediately dismissed all the doctors and servants in attendance and demanded that those remaining stay silent. He then gently placed his hand upon the boy’s brow and whispered quietly into his ear. The Tsarevich appeared to calm down, his metabolic rate slowed, his fever reduced, and the pain left him. It was a miracle! Or, at least, the Tsarina thought it was and she became in thrall to this simple Siberian peasant, this plain man from the mystical vastness of the Russian interior, this man of the soil, this Holy Man born without sin and thereby closer to God who could succeed where the greatest medical minds had failed. In the future, she was to become reliant upon him in all things, he could not be questioned, nor should he be, and he could not be interfered with.

Hereafter, Rasputin was to become an increasingly frequent visitor to the Imperial Court and could come and go more or less as he pleased and being no admirer of rank or status, he offended almost everyone of any importance he came into contact with. He was also often drunk, though never in the presence of the Tsarina. He rarely bathed or changed his clothes and spent his days seducing aristocratic women and his nights in brothels, bathhouses and dancing with gypsies.

He would boast of his relationship with the Imperial Family claiming that the Tsar had given him permission to penetrate the Tsarina whenever he wished and that he had free access to the bedrooms of the daughters. Whether his talk of having sexual relations with the Imperial Family had any truth in it seems unlikely but it was easily believed.

As far as Alexandra was concerned, he could do no wrong. He had been sent by God not just to preserve the life of the Tsarevich but the very existence of the Romanov Dynasty. Their relationship was to do untold damage to the reputation of the Imperial Family not just in real terms, but the rumour soon began to spread that she was Rasputin’s lover. This almost certainly wasn’t true; she was devoted to her Nicky but it was soon taken as a matter of fact with Rasputin’s own reputation for seducing aristocratic women going before him.

Tsar Nicholas shared with his wife the conviction that they had been appointed by God to rule. He was then an autocrat by both temperament and belief, but he was not of the strength of character to be one. He was incapable of taking the tough decisions required of a despot, but he was equally incapable of admonishing those who took such tough decisions in his name. It was a fatal flaw in his character which saw him take the blame for harsh acts of repression without ever reaping the benefits of them. Indeed, Alexandra would often demand of him that he be more of an autocrat, that he should dismiss those in Government who disagreed with his policies, exile those who opposed the regime, use troops to disperse rioters and never concede to demands for popular representation in the form of a Duma, or Parliament.

But Nicholas was only ever indecisive at best. Indeed, the joke was that the two most powerful men in Russia were the Tsar and the last person he spoke to.

Russia however was a country in transition, it was industrialising fast, and a proletariat was forming in the cities that would change the nature of the old Peasant State forever. Workers were banding together as never before with trade unions and political parties, though illegal, being formed and industrial unrest was increasing. The general sense of despondency was made even worse by the stream of bad news and reports of military failure coming back from Manchuria during the winter months 1904-05. The war with Japan was not going well and the lengthening casualty lists which come with defeat on the battlefield were causing alarm..

The situation was particularly poor in St Petersburg, where centred on the giant Putilov Steel Works industrial unrest and a wave of strikes had virtually shut down the city for over a month. The workers’ demands for higher pay, better working conditions and shorter hours went unheard and with neither side willing to yield no end to the dispute lay in sight. The workers still had one option available to them however – a direct appeal to the Tsar.

To the ordinary Russian the Tsar was thought an almost semi-divine father figure, someone above the self-interest of the moneymen and corrupt officialdom. On the advice, and under the guidance of a Russian Orthodox Priest Father Georgi Gapon, they would take their grievances directly to the one man they felt assured would listen and understand.

On 22 January 1905, as many as 100,000 striking workers and their families marched on the Winter Palace singing God Save the Tsar and carrying religious icons and banners with messages such as The Tsar is Our Father and Father, Help Us!

Unknown to the demonstrators the Tsar and his family had left the Winter Palace the previous week for their residence at Tsarskoye Selo some 15 miles distant and not for the last time he would be absent at a time of crisis and at a pivotal moment in his reign.

As the striking workers began to converge on the Winter Palace with Father Gapon at their head the decision was made to ring the Palace with troops. Despite the presence of the soldiers three or four deep and lined up as if on a parade ground, the mood among the demonstrators remained positive and non-threatening but the sight of so many people marching towards them many arm-in-arm sent ripples of panic through those in command and when the crowd refused to disperse and were within yards of the Palace Gates the order was given for the Imperial Guard to open fire. Dozens fell dead as the bullets ripped into the crowd and the white snow that glistened in the winter sunlight was soon spattered red and bathed in blood.

Around Father Gapon alone some 40 people lay writhing in agony on the ground and panic set in as those at the front desperately tried to get away from the firing that continued and many more were trampled to death in the crush.

The official figures for what became a massacre were 95 killed and 333 injured but it is widely believed that as many as 4,000 unarmed civilians were victims of the bloodshed that day.

What was too become known as Bloody Sunday was yet another political and public relations disaster for the Romanov Dynasty. It had always been felt that the Tsar loved his people, that for all the iniquities of Russian society, the corruption and the hardships endured he was the great moderator. They had turned to him for help, and he’d had them shot dead in the streets.

Learning of the events outside the Winter Palace the Tsar wrote in his diary of a “sad and painful day.” It was a sentiment not necessarily shared by his wife who had long insisted that he take a firm hand with such people, and no public apology or attempt to prosecute those responsible followed.

Bloody Sunday was not to prove the end of a crisis but the beginning of a far greater one. The blood that was shed that fateful day and the humiliation of defeat in the Russo-Japanese War was to spark a revolution in Russia’s urban centres that was to threaten the very existence of the regime and see the emergence of men previously unheard of such as Lenin and Trotsky as significant players in Russian politics for the first time.

The revolution had to be bloodily crushed by troops returning from the East as many of those stationed in the major cities were not considered reliable. But even this was easier said than done and the unrest rumbled on for many months.

The major demand of the more moderate elements among the opposition was the formation of a Duma. To the Tsar’s Ministers threatened with the violent overthrow of the regime this seemed the better of two evils. Even so Nicholas was reluctant to agree and when he finally did so on 18 February 1905, the proposals were so watered down that it merely served to escalate the violence. Alexandra was adamant that even this was a sign of weakness on his part and that the radical’s refusal to accept it was proof that she had been right all along - that give them enough rope and they will hang them all.

Despite the violent response of the Authorities the unrest continued but a watershed moment was reached when on 14 June, the crew of the Battleship Potemkin mutinied and murdered their Officers. If the spirit of revolution infected the military, then it was all over for the regime. Negotiations regarding the formation of a Duma resumed.

On 30 October, Tsar Nicholas signed into law the October Manifesto. It established the principle of Universal Suffrage, permitted the formation of trade unions and political parties thereby allowing for a lawful opposition for the first time, and it created an elected Duma as the central legislative body of the State. The Tsar could no longer act according to his whim, and it was the end of autocratic rule in Russia. As he signed the document he remarked: “I feel sick with shame at my betrayal of the dynasty.”

Alexandra could not have agreed more, all the problems that would beset Russia and their family in the future were caused by this one moment of weakness on his part, she would tell him.

Despite their anger and despair at having to yield to the demands of an ignorant and ungrateful rabble as they saw it, the passage of the October Manifesto saw some stability at last return to Russia. The Tsar remained the undisputed ruler of his Empire and he could dissolve the Duma if he wished, a power he exercised whenever they disagreed with him. This was never enough for Alexandra however who believed that he should have quashed all dissent regardless of the consequences of doing so. Better to have executed those who now formed the Duma not given them a role in Government. Perhaps it is to Nicholas’s credit that he listened to wiser counsel.

The establishment of the Duma helped quell the unrest but the potential for violence remained as did the threat of political assassination and being in the presence of the Tsar was no protection it seemed. On 1 September 1911, the Prime Minister Pyotr Stolypin was shot dead by an anarchist while attending a production in the Kiev Opera House just feet away from the Imperial Box where sat Nicholas, Alexandra, and their two eldest daughters. It was a particularly frightening moment and the safety of her family, particularly the Tsarevich, was to dominate the rest of Alexandra’s life to the point of paranoia where she saw conspiracies everywhere and trusted no one outside of her immediate circle not even those who had proved their loyalty over many years of devoted service.

The tragedy of Bloody Sunday was to be repeated seven years later on 17 April 1912, at the Lena Goldfields in Siberia when troops opened fire on striking miners killing 270 men, women, and children. Many members of the Imperial Family were shareholders in the Lena Gold Company including the Tsar’s mother, the Empress Maria, and responsibility for the massacre led directly to the Tsar. Once again Nicholas expressed his horror at events but did nothing – he was becoming a Tsar with a lot of blood on his hands.

Later that year while on holiday in Poland the Tsarevich had an accident that caused a severe haemorrhage. It seemed to everyone including the Court doctors that the young Alexei would die and there was nothing they could do to ease his pain. In her desperation Alexandra wrote to Rasputin in St Petersburg begging for his help. He wrote back immediately:

“God has seen your tears and heard your prayers. Do not grieve, the Little One will not die. Do not allow the doctors to bother him too much.”

Alexandra dismissed the doctors from Alexei’s bedside and read out Rasputin’s words to him. The Tsarevich gradually recovered and Alexandra already in awe of Rasputin was now more convinced than ever that he was a Holy Man sent by God for the protection of the Imperial Family. She would in future always refer to him as Our Friend and insisted her children do likewise. Tsar Nicholas who was always more sceptical, felt uncomfortable in Rasputin’s presence, did not particularly like him around his family, and was aware of the detrimental impact he was having on the reputation of the Imperial Family. As such, he maintained a discreet distance and was never so informal.

Rasputin by now a regular fixture at the Imperial Court was already casting a dark shadow over the family with whom he was now invariably linked and neither the Tsar or Tsarina could be spoken of without the name Rasputin being whispered in turn and the presence of this dirty, dishevelled peasant with the overpowering body odour was greatly resented in the glittering corridors of the Winter Palace. He was rude and discourteous to his social betters and liked nothing more than seducing their wives. His boasts of having free access to the bedrooms of the Tsar’s daughters, the implication being obvious, caused great offence.

When reports reached the Tsarina of Rasputin’s boasts, frequent drunkenness, lewd behaviour, and association with prostitutes she dismissed them as being the inevitable consequence of genius.

By 1 August 1914, Russia was at war with Germany and the Austro-Hungarian Empire and for the first time Tsar Nicholas found himself, genuinely popular as a wave of patriotism swept the country. No doubt he was overwhelmed by the adulation for the practicalities of waging a major war seemed to escape him.

Russia was woefully ill-prepared, mobilisation was painfully slow and the few munitions’ factories could not keep up with the demand for shells; many of the millions of men called-up could not even be provided with rifles, rolling stock was sparse and the lines of communication across the Russian hinterland were primitive to say the least. Despite all this optimism remained high and in the early months of the war all seemed well as the Russian juggernaut rolled into German East Prussia sweeping all before them. But it wasn’t long before German reinforcements turned the tide and the war was to become one of frequent defeat, demoralising retreat and ever mounting casualties.

Rasputin who had been absent from St Petersburg at the time war was declared recuperating in hospital following an assassination attempt in his hometown of Prokrovskoye wrote to the Tsar warning him against such a course of action:

“A terrible storm cloud hangs over Russia, disaster, grief, murky darkness and no light, a whole ocean of tears there is no counting them, and so much blood. I can find no words to describe the horror we will all drown in blood. The disaster is great, the grief infinite.”

For once his words were ignored.

The logistics of waging war may have passed him by in the patriotic fervour that had gripped the country, but Nicholas remained mindful of the fact that the love being showered upon him did not extend to his wife. The Russian people remained well aware that she was German, but he thought it an opportunity for her to prove her loyalty to her adopted country.

Despite the fact she was German Alexandra remained firmly behind her husband and volunteered to train as a Red Cross Nurse. Though she spent many hours at the bedside of convalescing soldiers she could hardly be said to have got her hands dirty. It was felt improper that she should be subjected to the horror of war and the worst wounds were shielded from her, at least until she demanded otherwise. She also felt ill at ease in the presence of ordinary Russian soldiers, but she enjoyed chatting to Officers from the better Regiments and it was felt that her presence alone was enough to raise morale.

By 1915 the war had turned against Russia and the early successes of the previous year had become a distant memory.

Heavy defeats at the Battle of Tannenberg and later the Masurian Lakes and Gorlicky Tarnow saw their army in full retreat. Their failure however was as much down to the continuing logistical deficiencies and problems of supply as it was any strategic or tactical failure on the part of its Commander Grand Duke Nicholas who despite some initial chaos and a spate of desertions managed the withdrawals in relatively good order.

Tsar Nicholas however thought otherwise. He had always felt more comfortable in the presence of soldiers and working within the rigid command structure of the army than dealing with squabbling politicians and the problems of administration and government, and he was eager to escape the constant scheming and grubby politics of the Imperial Court.

In September 1915, encouraged by Alexandra who believed that the simple Russian peasant soldier would fight better for the person of the Tsar, he dismissed Grand Duke Nicholas travelled to the front and took personal command of the army. He was to prove no strategist, and little changed as a result of his presence at the front but it was to have dire political implications. Now the failures of the army led directly to him and his absence from St Petersburg left a power vacuum at the heart of Government.

Any crisis of Government that might result from the Tsar’s absence could be taken care of Alexandra believed. While her husband was away at the front she would rule in his name.

Alexandra was in charge, but it was Rasputin who was making all the decisions. As the war went from bad to worse, the problems of supply mounted, and dissent grew, the Duma demanded that changes be made. Alexandra who hated the Duma with a passion refused to co-operate with them and so they in turn appealed directly to the Tsar.

In the meantime, Rasputin appointed one incompetent Minister after another only to dismiss them a few weeks later. In little over a year, he appointed 4 Prime Ministers, 4 War Ministers, and 6 Ministers of the Interior among many others. Some he did so out of favouritism, others on a whim. He also regularly took bribes not out of any love for money because he regularly gave it all away but simply because he could.

The Tsar isolated at the front was bombarded not by enemy shells but by official telegrams from home, some from the Duma demanding that he act before the war was lost and remove Rasputin from all positions of influence, others from his wife praising the work of Our Friend and that he should prove himself the autocrat by dismissing the Duma who she thought were deliberately seeking to undermine the Dynasty. In turn, they believed her, along with most of the Russian people, to be a German spy who was working for Russia’s defeat.

Under pressure Nicholas agreed to exile Rasputin from St Petersburg, since renamed Petrograd because of its German connotations, and for a short time at least some semblance of normality returned to the capital, the efficiency of the Administration improved, and Court life took on a more familiar look, but the decision plunged Alexandra into despair.

In turning against Rasputin, the Tsar had acted against the Will of God. They would all be cursed and what would happen if the Tsarevich fell ill? She wrote to her husband begging that Rasputin be permitted to return. As usual Nicholas was incapable of denying his wife anything, he permitted Rasputin to return. It was yet another disastrous decision among many.

The strain of it all was proving too much for Alexandra who now often took to her bed and had to be pushed around in a wheelchair. She now refused to discuss policy, once a decision was made it was made, and any dissent was often met by a hysterical outburst. She trusted only in Rasputin and God and was incapable of distinguishing between the two.

By mid-1916 the situation at the front had stabilised somewhat. The Brusilov Offensive in the South which had begun on 4 June had proved a startling success with the Russians breaking through the Austro-Hungarian lines and capturing hundreds of thousands of prisoners. But if morale had improved at the front it was collapsing at home. Food was scarce, inflation rampant, strikes on the increase and protests against the war commonplace. The crowds now thronging the streets were reinforced by thousands of politicised deserters from the front, many still in uniform and many still armed. By September the Brusilov Offensive upon which so much had hinged had petered out and the Russian Army was once again in retreat. There was still no victory and no end to the war in sight.

At the insistence of the Chairman of the Duma, Mikhail Rodzianko, the Tsar briefly returned to Petrograd where he addressed the Duma in person and praised them for their sterling work during difficult times. His words were warmly received, and he felt confident that he had their full backing for his handling of the war. As far as Alexandra was concerned however it was a betrayal. Only Rasputin could be relied upon, she said, and some of those in the Duma had not only demanded the arrest of Our Friend but even his execution. The Tsar of all the Russia’s should be ashamed of himself.

Delighted though he had been to see his family once again, a battered and bruised Nicholas returned to Army Headquarters at Mogilev relieved to leave the cesspool of political intrigue and personal animosity that was Petrograd behind him.

The problem of what to do with Rasputin had not gone away, however. His pernicious influence seemed to be everywhere and if the Tsar would not remove him then the responsibility would have to fall to another. In early December 1916, the right-wing politician Vladimir Purishkeyvich made a speech in the Duma in which he lambasted Rasputin in the most graphic terms:

“A dirty, illiterate peasant is playing with our judgement, what a place he is taking us into. I want to sacrifice myself and kill this vile creature. Evil comes from those dark forces, from the influences headed by Rasputin, the evil genius of Russia.”

Present that day to hear Purishkeyvich was Prince Felix Yusupov, he was greatly impressed.

Prince Felix Yusupov was the richest man in all Russia after the Tsar, but he was little admired. Tall and handsome he had a feminine demeanour and did little to hide either his homosexuality or his love of dressing in women’s clothes. At a time of great trauma for Russia his flamboyance and refusal to serve his country in any capacity made him a figure of ridicule. The Grand Duchess Olga Nikolaevna wrote to the Tsar in criticism of him: “What a thoroughly unpleasant impression he makes, virtually doing nothing, a man idling in such times is a disgrace.”

In an attempt to deflect further criticism Yusupov trained as an Officer Cadet but he never joined a regiment, and it was said that he just enjoyed parading around Petrograd in his uniform. It fooled no one.

The day after his speech Purishkeyvich received a telephone call from Yusupov, together they would murder Rasputin and that to do so would be a patriotic act. Yusupov’s reasons may have been more personal, however. It was rumoured that he and Rasputin had had a homosexual affair but that his advances had recently been spurned. The subsequent brutality of the assault on Rasputin’s person provides some credence for this.

Rasputin had long been aware that his life was in danger. In the autumn of 1916, the Tsarina had been presented with a letter. It was addressed to her husband and contained a warning:

“Tsar of the land of Russia, if you hear the sound of a bell that will tell you that Grigori has been killed, you must know this: if it is your relations that have wrought my death then no one in the family, that is to say none of your children or relations will remain alive for more than two years, they will be killed by the Russian people.”

Alexandra struck down with foreboding did not show the letter to Nicholas.

On the night of 16 December 1916, Rasputin was lured to the palatial home of Prince Yusupov on the pretext of attending a party and of meeting the Prince’s wife Irina, considered one of the most beautiful women in Russia.

The intended party had earlier come to the attention of Anna Vyrubova who was aware that the Princess Irina was not present in Petrograd having already journeyed to the Crimea. She suspected that the party may not be as innocent as it appeared but declined to relay her suspicions either to the Tsarina or Rasputin.

Upon his arrival at Yusupov’s grand residence in the Moika Palace Rasputin was taken to the cellar where he was told that the other guests were just departing and that in the meantime he should tuck into the wine and cakes both of which had been liberally laced with cyanide. The truth was that besides Rasputin and Yusupov the only other people in the Palace that night were Purishkeyvich, the Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich and the mysterious Dr Lazovert.

The poisoned cake and wine did not have the effect that the conspirators had hoped for, and the murder of Rasputin was to be a messy and muddled affair. In the end he was poisoned, shot, and brutally beaten. Even so, it is said that he either drowned or froze to death after being thrown into the Neva River.

Rumours swept Petrograd concerning the mysterious disappearance of Rasputin and Alexandra was desperate for news of his whereabouts. It was resolved two days later when his body was plucked from the icy water. Alexandra, who still had Rasputin’s letter of warning in her possession swung from bouts of hysterical grief to feelings of despair and resignation. Rasputin had predicted that she and her entire family would be killed if he was harmed by any of their relatives and both Prince Yusupov and the Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich were cousins of the Tsar.

Alexandra demanded that the assassins of Our Friend be immediately arrested, tried, and executed. Nicholas for once refused to yield to his wife’s demands – he would not hear of any such thing – and the assassins were permitted to leave the city.

The murder of Rasputin did little to improve the political situation in Petrograd and by early February 1917, the absence of deference had reached frightening proportions and all authority had begun to break down with many of Russia’s other major cities similarly in turmoil. In many places workers had downed tools and a series of strikes had paralysed the economy, street protests were commonplace, and shops were either closed or had been looted. Those troops who had been expected to restore order had either handed over their weapons to the demonstrators, joined the protests themselves, or simply returned to barracks, some had even turned on and killed their Officers.

Rodzianko sent increasingly frantic telegrams to the Tsar begging him to return to Petrograd and form a new Government as the only way of saving the Dynasty, they went unanswered. In the power vacuum that ensued the Duma was forced to act and established a Provisional Government to work alongside the recently formed revolutionary Soviet of Soldiers and Workers Deputies. Almost its first act was to take those members of the Imperial Family present in Petrograd into custody.

Upon being informed that his family had been placed under arrest a shocked and outraged Nicholas at last decided to act. He made haste for Petrograd but upon learning that the railway line he had intended to use had fallen to the revolutionaries he switched to one controlled by General Nikolai Ruzzki, the Commander of the Northern Armies.

Upon his arrival at Ruzzki’s Headquarters he received a frosty reception and was curtly informed by the General that he now only took orders from the Provisional Government and that he had received no notification that the Tsar should be permitted to proceed to Petrograd.

In desperation on 15 February, the Tsar wired the Executive Committee of the Duma and its new Chairman Prince Grigori Lvov granting him permission to form a new Cabinet. In response he received a telegram from the previously loyal Mikhail Rodzianko demanding his immediate abdication. Nicholas initially refused remaining adamant that the Romanov Dynasty would not cease to exist under his watch, but he was too far removed from the centre of power to any longer influence events. With all power effectively having been wrenched from his hands he had little choice but to sign. He did so however with a heavy heart and no little sense of betrayal, but the safety of his family came first.

The now ex-Tsar was re-united with his family at Tsarkoye Selo where they were kept under close house arrest. At first the Romanov’s, as they were now known, were well treated and permitted to keep their servants and maintain many of the trappings of the old Imperial Court. On 13 August, however, the Provisional Government now dominated by the ambitious young lawyer Alexander Kerensky ordered their removal from the capital city to Tobolsk in the Urals. It was for their own safety he said, though in truth he did not know what to do with them.

In the meantime, Kerensky’s determination to continue to prosecute the war was to prove a serious error of judgement. He had visited the army earlier in the summer and had determined that their morale was high. The offensive he launched in July based as it was on his faith in the loyalty and courage of the simple Russian peasant was a catastrophe as the army after some initial success displayed the first signs of disintegration and simply melted away.

The failure of the July Offensive and the inability of the Provisional Government to bring an end to the war seriously undermined it and lead to its downfall just a few months later.

In captivity Nicholas, who had always been a better family man than he had ever been an autocrat, seemed almost relieved at no longer having the responsibility of being Tsar. He remained cheerful throughout and felt confident that his application for asylum in Great Britain would be accepted by his cousin King George V and initially it seemed that it would but when later it was denied by the British Government it came as a shattering blow. Even so, he did not allow his disappointment to filter down to his children continuing to reassure them that everything would be fine.

Reassuring his wife was another matter however, she was downcast and pessimistic and more demanding of him than ever. She was convinced that they were all to be punished for the murder of Rasputin just as he had predicted and there was nothing the Tsar could say or do to deflect her from this view.

The October Revolution and the coming to power of the Bolsheviks changed everything for the ex-Imperial Family, rather than being treated as guests of the Provisional Government they were now effectively political prisoners considered enemies of the state liable to prosecution and punishment.

In April 1918 the family were removed to the Ipatiev House in Ekaterinburg where the regime was considerably harsher. The Bolsheviks were professional revolutionaries unaffected by sentiment or any sense of deference or nostalgia. As far as they were concerned the Romanov’s were criminals who as long as they remained in Russia or indeed alive would serve as a rallying point for the forces of reaction.

They were placed under armed guard and closely always monitored, they were also denied luxuries such as coffee and cigarettes and forced to eat soldier’s rations. The guards also regularly mocked the Tsarina and her daughters who were often subjected to lewd remarks, gestures and sexual innuendo of all kinds. The walls of the courtyard were adorned with sexually explicit graffiti that shocked and appalled Alexandra. Nicholas, though certainly no less offended shrugged it off. It was just soldiers behaving as soldiers do.

During the day the family were allowed to wander the grounds and Nicholas would spend much of his time with the young Alexei. Both had always enjoyed the outdoors and manual labour and together they would garden and chop wood. The girls would often remain indoors sewing with their mother to avoid the lewd comments and crude remarks of the guards.

In the evening Nicholas would drink coffee and smoke cigarettes that he had managed to procure from some of the more sympathetic guards and regale his children with stories. He did everything he could to maintain their spirits.

By mid-July 1918, the sound of gunfire could be heard in the distance and with the passing of every day it appeared to be getting closer. It was in fact the Czech Legion of the anti-Bolshevik White Army closing in on Ekaterinburg. The prospect of the Romanov’s liberation loomed large. It was a scenario that could not be allowed to endure, and it was to seal their fate.

Nicholas was excited at the prospect that their liberation might be at hand and remained confident that at the very least a deal could still be struck that would secure their release. He played down his optimism in the presence of Alexandra who was convinced that it would never happen. Indeed, her lugubrious presence and precarious state of mind did little to relieve the burden placed upon Nicholas to shield the children from the reality of their situation. She feared for her husband’s life, she feared that her daughters would be sexually molested or worse and she feared that the young Alexei would have an accident or fall ill and be denied treatment.

No doubt Nicholas shared her concerns but unlike him she was incapable of putting on a brave face or creating a positive facade. She complained regularly about the rudeness of the guards, the lack of deference they were shown, the poor quality of the food. She was often close to tears, both of anger and of anguish and was more cloying than ever. Yet even in these dark times, Alexandra and Nicholas, whose love for one another had never been in doubt, became closer than ever before.

In early July, Yakov Mikhail Yurovsky took command of the Ipatiev House. He was a dedicated Bolshevik hardened by years of revolutionary activity, exile, imprisonment, and the rigours of war.

He was a much harsher man than his predecessor, stern, humourless and generally unsympathetic who was later described by some of those who delivered food to the Ipatiev House as being chilling. He increased the number of guard posts, imposed a curfew, and restricted the family’s freedom to move around the grounds. Yet he also ensured that the family’s provisions were delivered to them un-pilfered by the guards and returned personal belongings to the Tsar that had earlier been stolen.

In the late afternoon of the 16 July, ten members of the Cheka, the Bolshevik Secret Police, arrived at the Ipatiev House. It remains unclear whether they had been sent by the Ekaterinburg Soviet on the direct orders of Lenin or had been requested on the initiative of Yurovsky, himself.

The likelihood is that the coming events had been planned for some time and though the exact details of the discussion Yurovsky had with the men from the Cheka remain unsubstantiated he is reported to have said: “Then we must shoot them all tonight.”

That night Alexandra made her last entry in the diary that she had maintained throughout their captivity:

“Grey morning after lovely sunshine. Tatiana started to read from the prophet Obadiah – though thou exalt thyself as the eagle and set thy nest among the stars, thence will I bring you down, sayeth the Lord – played bezique with Nicholas. 10.30 too bed – 15 degrees.”

In the early hours of 17 July, Yurovsky sent for the Tsar’s doctor Eyvgeny Botkin and told him to rouse the family.

Nicholas, who had learned to assert an authority whilst in confinement that he had so often lacked as Tsar, demanded to know why he and his family had been dragged from their beds in the middle of the night. Yurovsky told him that they were to be removed to the cellar for their own safety and that they should also dress to have their photograph taken. The picture, he said, was to be distributed to the foreign press to show the world that they were alive and being well treated. The Tsar was disgruntled by the imposition but complied.

The family hastily dressed before being led down to the cellar along with the doctor, their cook, the Tsar’s valet, and the maid. The daughters took small cushions with them, and the Tsarina requested a chair for herself and the Tsarevich which were duly provided. The family then lined up in anticipation of having their portraits taken. Once they had done so Yurovsky ordered in the Cheka who set up a machine gun.

Yurovsky then curtly informed the Tsar that they were to be executed on the orders of the Regional Soviet. There was silence except for the audible gasps from the family and a brief pause before the Tsar walked forward and simply said “what?”

Yurovsky taking out his revolver shot him through the chest, he then ordered the Cheka to open fire.

The servants were shot first before the guns were turned on the family themselves. The Tsarina tried to shield her son but was killed almost instantly. The children however did not die so easily. They had been busy in the previous months sewing jewels into their dresses and these prevented the bullets from penetrating. The guards had to bludgeon and bayonet them before they were finished off with shots to the head with Yurovsky personally dispatching the Tsarevich and the Grand Duchess Tatiana.

Yurovsky later wrote of the night’s events and of his impressions of the Imperial Family. The Tsar he personally liked saying:

“He was an ordinary gentleman, simple, and very much I would say, like a peasant soldier.”

His impression of the Tsarina was less favourable – proud, haughty and domineering, he said.

The Grand Duchess Tatiana he remembered as being the most intelligent and mature of the girls whilst Anastasia was pretty and charming. But he was always to be conflicted by his encounter with the Imperial Family:

“It was impossible not to hate what the Imperial Family represented and have bitterness for all the blood of the people that had been shed on their behalf. Yet even with these feelings it was difficult for me to view them in this way. One could not but find such simple, unassuming and generally pleasant people as enemies. Had I not been given my charge it would have been difficult for me to have anything against them.”

The truth was he had been determined to settle the score with the Romanov’s for centuries of oppression, but he was clearly shaken by what he had done, and though he never explicitly expressed regret for his actions it was clear to those who knew him that he was haunted by it. Indeed, a British Army Officer who met him some two years later wrote:

.”

“The man who led the execution squad was filled with remorse and horror at having murdered the Imperial Family”.

There still remains some doubt regarding the fate of the Tsar’s youngest daughter the Grand Duchess Anastasia as neither her body nor that of the Tsarevich were initially recovered along with the others, though it is claimed that they have been since.

A woman known as Anna Anderson was to claim to be Anastasia, the last surviving member of the Imperial Family, and fought to be recognised as such until her death in 1984.

She convinced many among the Tsar’s relatives that she was the woman they had known as a little girl but significantly not all. A private investigation paid for by the Tsarina’s brother the Grand Duke of Hesse claims to have revealed her to have been an emotionally unstable Polish factory worker named Franziska Schanzkowska, which she denied.

If it had been proved that she was Anastasia, then not only would she have become the effective heir to the Russian throne but could have laid claim to the vast Romanov wealth that had been smuggled out of Russia following the revolution.

Before the remains of the Imperial Family were reburied in 1994, D.N.A tests carried out appeared to confirm that all the family died in the Ipatiev House.

Unfortunately, there could be no corresponding test done with the remains of Anna Anderson whose body had long since been cremated.

Share this post: