Battle of Camerone: Making of a Legend

Posted on 13th May 2021

Formed in March 1831, the Foreign Legion was never intended to be an elite unit of the French Army, recruited as it was from men of other nations of whom few questions were asked thereby becoming a haven for ne’er do wells evading justice and political dissidents hiding from the prying eyes of the secret police.

Led by French Officers who had few illusions about the character of the men under their command discipline was harsh and punishments severe with little expected of them other than a strict obedience to orders.

They were after all disposable, so little trusted that they were not permitted to serve in mainland France, their role to do the dirty work of the French Army in its colonial possessions and the monotonous chores of an occupying force – the manning of remote outposts, the suppression of rebellion, the maintenance of law and order – to be the visible presence of French authority in those distant lands it claimed as its own.

It would be sometime before this bastion of colonial policing would forge a reputation for combat, but the opportunity would come and in an unexpected place.

On 30 April 1863 in the hot barren landscape of the Mexican desert at a place known as the Hacienda Camaron the legend of the French Foreign Legion as a unit that fought to the last bullet and the last man was born. The fact they were in Mexico at all only added fuel to the fires that make legends burn so bright.

On 17 June 1861, the Mexican President Benito Juarez declared that he was suspending the payment of interest on the country’s debt, a decision taken arbitrarily without consultation or negotiation which greatly angered its creditors, most notably Britain, Spain and France who taking advantage of the inability of the United States to intervene as a result of the Civil War then raging demanded that Mexico resume payments immediately. If not, they would be forced to comply. In a deliberate act of intimidation, a British Fleet was despatched to patrol in Mexican waters and a Spanish Army briefly occupied Vera Cruz but this combined effort soon faltered when it became apparent that the French had territorial ambitions in Mexico.

The Emperor Louis Napoleon III, a distant relative of Napoleon Bonaparte was eager to emulate the achievements of his more illustrious namesake and saw in Mexico the ideal opportunity to carve out for France a trans-Atlantic Empire.

The Confederate Government in Richmond, which at the time appeared to have the upper hand in the American Civil War and desperate for international recognition offered its support for French intervention in Mexico which compensated somewhat for the hasty withdrawal of Britain and Spain. Duly encouraged, on 5 March 1862 a French Army under the command of General Charles de Lorencez landed at Campeche confident of a rapid advance on Mexico City and a swift conquest but such expectations were soon dashed, and victory was to remain elusive.

On 5 May, they were defeated at the Battle of Puebla and forced to withdraw in some disarray not finally stabilising the situation until the 14 June when they took up defensive positions around the town of Orizaba to await reinforcements from France.

They were not to renew their advance until the late autumn taking the town of Xalapa on 12 December and the following month capturing Vera Cruz. French firepower was at last beginning to tell and by 16 March they were once again besieging Puebla but initially surprised by the effectiveness and courage of the Mexican Army they were no longer under any illusions and expected stubborn resistance and a prolonged siege.

A convoy was hastily organised to carry munitions, millions of French francs to pay the troops and gold bullion to bribe the defenders but its escort was deemed too insignificant for such a dangerous mission so it would be reinforced by the 3rd Company Foreign Legion.

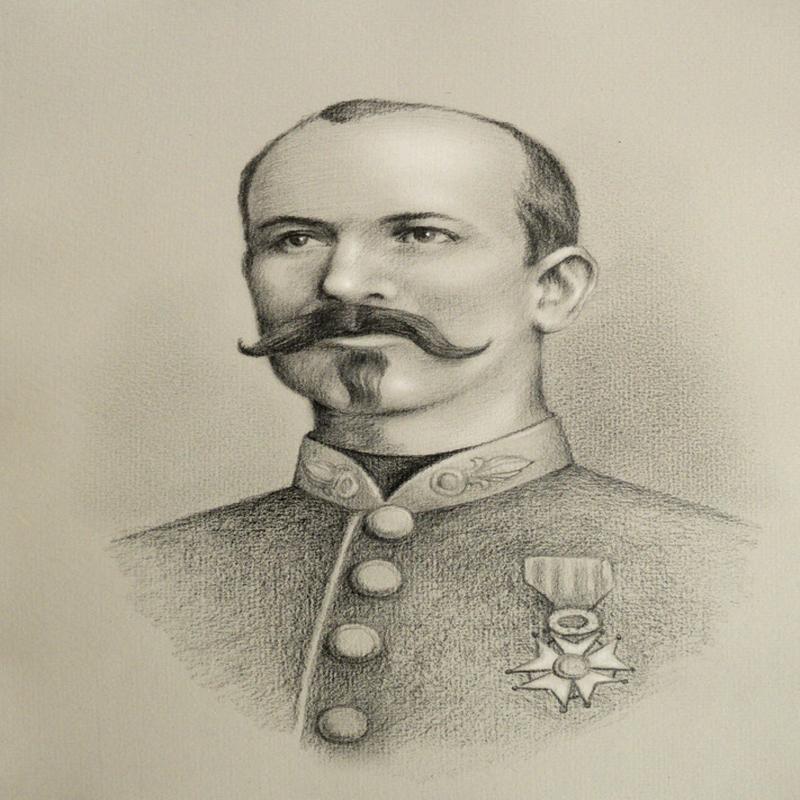

But 3rd Company had been struck by illness and disease and half its compliment and all its Officers were incapacitated and so in the absence of anyone to lead it the Regimental Adjutant Jean Danjou volunteered to do so. He, in turn, recruited two further Officers, Lieutenant Jean Vilain and Lieutenant Clement Maudet to accompany him.

Captain Danjou was an experienced Officer who had fought in the Crimean, Italian and North African campaigns and had the scars to prove it. Whilst serving in Algeria he had lost his left hand when the rifle he was using misfired and exploded. To disguise his disability, he purchased a wooden hand to replace the one he had lost which he wore at all times covered by a white glove.

A career soldier he had been delighted with his promotion to Adjutant, but he missed front-line service and the opportunity to escort the convoy was one not to be missed. His fellow Officers also saw it as the opportunity for adventure, but the dangers could not be underestimated.

A force of just 3 Officers and 62 men seemed a meagre escort for such a valuable cargo and Danjou was advised to await reinforcements but he had confidence in his men, and he had confidence in himself.

The trek to Puebla across a fly infested landscape largely devoid of cover amidst choking dust and in intense heat did not make for a scene of glory – progress would be slow, and they were vulnerable to attack especially from fast moving cavalry.

The convoy of 60 wagons and 150 mules left Vera Cruz for Puebla under the cover of darkness in the hope of maintaining the secrecy of its departure but with the long days to come and hampered by the difficult terrain their presence would be revealed soon enough.

Slowed to the pace of its dismounted escort there could be no swift flight from imminent danger, so caution became Captain Danjou’s watchword as he divided his command into two columns positioning them at a distance of 100 yards either side of the convoy to protect its flanks whilst he scouted ahead with a small detachment seeking advance warning of any enemy incursion.

The first day of the march had been trouble free and no reports of enemy activity received so they rested at the village of Chiquihuite from an arduous journey made under a blazing sun which in their heavy woollen uniforms of blue tunics and red pantaloons caked in sweat and sticking to their skins, weighed down by backpacks and heavy smoothbore muskets saw the stark reality of exhaustion and the constant yearning for water to moisten their lips and clear their dust-filled lungs belie the colourful and vivid image they struck in the grim and featureless landscape.

Departing Chiquihuite they had marched some ten miles when they rested but no sooner had the arms been stacked and the coffee brewed than a report was received that enemy cavalry barred the road and were advancing toward them. Danjou, who had rejoined the column aware that the convoy could be easily overwhelmed in open country, ordered it to head for the seemingly deserted Hacienda Camaron nearby.

Unknown to Danjou, the motley collection of broken-down huts and out-houses had already been occupied by Mexican snipers and under enemy fire many of the convoys handlers fled and the mule train was scattered. As a result, he tried to draw attention away from the convoy by confronting the advancing Mexicans head-on and ordered the formation of a Square for mutual protection and to maximise firepower but in their haste to form up a unit of sixteen men had become isolated and taken prisoner.

Reduced to just 3 Officers and 46 men the sight of this insignificant band of Legionnaires seemingly prepared to make a fight of it only served as a provocation to the Mexican cavalry which charged with reckless abandon across open country and into a thunderous volley of musket fire suffering grievously as a result before withdrawing in some disarray.

As they continued to hold their position in defiance of repeated enemy attacks Danjou began to despatch his men in small groups to take up defensive positions in Camaron with orders to clear it of snipers which they failed to do.

Despite the danger of enemy fire Camaron did at least afford some protection, it had a partial high wall and the small clump of houses where the Legionnaires had taken up their defensive position could only be accessed via a narrow courtyard. As a result, Danjou, believing that he had merely encountered a Mexican reconnaissance in force remained confident that he could hold out even if his original plan of fighting from behind the high wall had to be abandoned due to the intensity of enemy sniper fire.

The Mexican Commander Colonel Francisco Paula de Milan was no less confident despite the early setbacks his 800 cavalry were soon to be reinforced by 1,200 infantry, an overwhelming force that through sheer numbers alone doomed the French opposing them to defeat. He called upon Danjou to surrender but to his astonishment he refused declaring that – we have the ammunition; we will not surrender. He then broke open a bottle of wine, took a sip, and swore an oath to fight to the death. He then summoned his men to take the same oath, which they did.

A furious Milan ordered his cavalry to attack at once but unable to manoeuvre in the narrow confines of the courtyard they were sitting targets and repulsed with great loss of life.

But surrounded and under a constant rain of fire French casualties were also mounting yet blooded and exhausted though they were, without access to water, low on ammunition and with no hope of relief they fought on exhorted to ever greater efforts by the omnipresent Danjou until struck down by a sniper’s bullet and shot through the chest, he died.

Shorn of their inspirational leader surely now the surviving men would see sense and lay down their arms, but Danjou’s replacement Lt Vilain would prove no less determined. He shouted to his men: “I command you now, and tell you – we may die but we will never surrender!” Many had already died and would continue to do so as the Mexican Infantry closed in and the fighting intensified. At 5 pm, some three hours after the death of Danjou, Vilain was himself killed trying to clear enemy troops off the high wall.

A brief lull in the fighting now followed as Colonel Milan approached the French lines under a flag of truce, the sight that greeted him was one of slaughter with bodies burned by the sun and infested with flies piled up before the defences both French and Mexican together in an undignified but eternal repose.

Now under the command of Lt Maudet and confined to a stable with the roof burned off and a partially destroyed ranch house kept under constant fire by enemy troops in the courtyard outside there were only 12 Legionnaires remaining some of whom wounded with bloodied faces and uniforms torn to shreds were barely able to stand. With the situation utterly hopeless they were called upon once again to surrender but still they refused – they had sworn an oath to fight to the death and they would honour it. They were also fearful after such a protracted and bloody struggle what might become them should they fall into Mexican hands.

Colonel Milan was troubled by a sense of guilt, perhaps even despair – more men would die and for what, glory? To which the answer appeared to be, yes.

As the sun began to set on a day of carnage and death Maudet with just five men remaining, their ammunition expended, ordered fix bayonets and charged the Mexican lines. Two were shot down almost immediately, a third, a Belgian, was killed trying to shield the wounded Maudet (who would die soon after) while the remaining Legionnaires had to be quite literally beaten into submission.

It was a dramatic end to a day of brutal struggle, of endurance, fortitude and courage from the men of both sides. Of the 46 Legionnaires who had fought behind the mud and brick defences of the Hacienda Camaron 43 had been killed, 1 found wounded, and 2 captured.

The Mexicans had lost some 300 men, 190 of whom had been killed in what would prove a pyrrhic victory, for Danjou, though he had not lived to see its fruition had succeeded in his plan to draw attention away from the convoy which, with the exception of the mule train, escaped back to the town of La Soledad largely intact.

Disarmed and helpless the two surviving Legionnaires were asked sarcastically if they might now consider surrender but still, they remained defiant demanding instead that they should be permitted to recover the body of Captain Danjou and bury it with full military honours. In response Colonel Milan could only splutter: “What can I refuse to such men – no, these are not men, they are devils!”

Captain Danjou’s prosthetic hand lost in the immediate aftermath of the battle was later recovered and returned to the Regiment. It is now carried with pride at the head of the Foreign Legion’s annual Camerone Day Parade.

But as is so often the case in war glory is not always the offspring of victory and Louis Napoleon’s incursion into Mexico was to prove a fiasco and a curb to his Imperial ambitions. Yet at first, after some initial setbacks, everything had seemed to go so well. On 17 May 1863, Puebla, the last major barrier to an advance on Mexico City surrendered and two weeks later President Juarez fled the capital which the French occupied without a shot being fired in its defence – it appeared that Mexican resistance was crumbling. In the meantime, Louis Napoleon preferring to rule by proxy rather than establish a permanent French occupation of Mexico persuaded the Habsburg Duke Maximilian Ferdinand to take the throne. With the support of the Mexican aristocracy, the Catholic Church, and he believed French troops the hapless Duke agreed and was installed as Emperor Maximilian I on 3 October 1863, though he didn’t arrive to take up residency in his new realm until May the following year.

But it was clear from the outset that he had little, if any, support among the people and ex-President Juarez had not fled but was rallying Republican forces in the countryside. His army was incapable of preventing the French from occupying town after town but outside of the urban areas Mexico was already proving ungovernable.

Following the conclusion of the Civil War in America the United States Government asserting the tenets of the Monroe Doctrine made it clear that it opposed French intervention in Mexico and sent a large army to patrol its southern border threatening an intervention of its own. They also provided the Juaristas with weapons and supplies.

Fearing conflict with the United States and under pressure from a resurgent Prussia at home Louis Napoleon without consulting his allies decided to abandon Maximilian and evacuate Mexico.

On 31 May 1866, the French Army began its embarkation for home but despite repeated requests to do so Maximilian refused to go with them. His sense of duty, he declared, dictated that he must remain and displaying a sense of honour that not shared by his erstwhile ally he refused to abandon to their fate those who had been loyal to him. By doing so he signed his own death warrant.

Without French military support, outnumbered, and poorly armed by comparison with their opponents the Mexican Imperial Army went down to a series of crippling defeats – it could only be a matter of time before the regime fell.

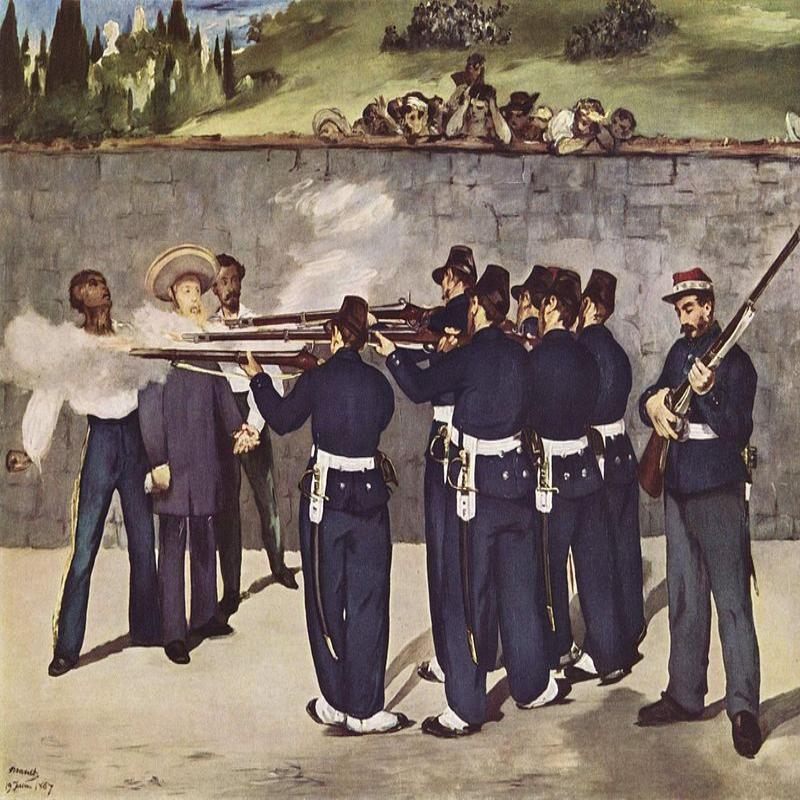

In May 1867, the Emperor Maximilian was captured trying to escape the net that was closing in around him and there was too be little of the respect or deference considered due to the scions of a Noble House and certainly not that afforded to Louis Napoleon by the Prussians just three years later.

On 17 June 1867, in the town of Queretaro the Emperor Maximilian I of Mexico was executed by firing squad.

Louis Napoleon’s dream of creating a vast Catholic French Empire in central and southern America had ended in the nightmare of betrayal, abandonment and humiliation. Yet in France itself his campaign of risky adventurism and Imperial hubris was soon forgotten except for the events at the Hacienda Camaron where the Foreign Legion had become part of the nation’s consciousness with a reputation for valour beyond the call of duty that had been written in its own blood.

Tagged as: Miscellaneous, War

Share this post: