Battle of Crecy (1346)

Posted on 3rd May 2022

On February 1, 1328, Charles IV, King of France died. Before his death, with no legitimate male heir, he nominated his niece Joan of Navarre to succeed him. Instead, his cousin Philip of Valois usurped the throne, a fait accompli that was soon after enshrined in law. It meant a change of dynasty of course, and the end of the Capetian inheritance.

The English King Edward III, who was soon to assert his own claim to the French Crown believed Philip of Valois and his successors to be illegitimate while he as the son of Queen Isabella the so-called ‘She-Wolf of France’ and sister of Charles IV, was the rightful heir.

Ever since he had cemented his authority as King by having his mother confined to a convent and her lover Sir Roger Mortimer executed, he had long harboured the ambition to establish English dominion in France. In May 1337, King Philip V provided Edward with the excuse for doing so when he occupied his possessions of Aquitaine and Ponthieu on the grounds that the English King had failed to fulfil the obligations demanded of him as a vassal of the King of France. As far as Edward was concerned, he was no vassal and the seizure of English possessions in France was theft plain and simple – it was the beginning of the Hundred Years War.

But his campaign against the French which had started so brightly with a stunning naval victory at the Battle of Sluys on 24 June 1340, soon became bogged down in a series of sieges, counter-sieges, and forced marches that were going nowhere and achieving nothing. Finally, forced to return home with little other than a truce in place his campaign was deemed a failure, and worse still, an expensive failure.

Yet regardless of any prior humiliation he remained determined to resume hostilities as soon as possible. His Parliament did not agree however, and they were reluctant to provide the funds for their King to pursue his personal and dynastic ambitions. As frustrated and angry as he was Edward remained undeterred and if Parliament would not do his bidding then he would raise the money himself even if this would prove more difficult than he had first thought. The Florentine bankers upon whom he had previously relied for extra funding had since fallen upon hard times and were unable to help. His advisers suggested there was an even more lucrative source of finance and one closer to home, however.

The wool trade was the most profitable in England and one over which the King wielded considerable control. He not only decided its rate of taxation but also the ports where the wool merchants could operate.

Already a powerful monopoly the wool merchants had long been concerned at French interference in their plans to expand further into the Netherlands and the Low Countries; for a favourable consideration they might be willing to provide the money the King required. Learning of this those in Parliament whose prosperity did not rely upon the wool trade fearing that the King’s private financial arrangements would undermine their role as the money raising chamber upon which the Monarch relied now provided funds of their own, even if they did so reluctantly and through gritted teeth.

With the finance in place goods were purchased in haste, supplies stockpiled and ships requisitioned; so, also were troops raised mostly from Wales and the West Country. Despite the very real risk of death either in battle, by drowning, or of disease the prospect of plunder meant there was no lack of recruits.

Having seized control of the Channel following his victory at Sluys, Edward was able to transport his army to France unopposed landing at St Vaast on the Contentin Peninsular on July 12, 1356. Yet his army of 12,000 archers’ expert with the longbow, 2,400 knights and men-at-arms along with a few thousand Welsh and Irish spearmen (of little use in battle but good for spreading terror among the local populace) hardly seemed adequate to the task Edward had set himself, and so it would prove.

He also didn’t appear to have any cohesive plan in place and having rampaged through Normandy where the plunder was good burning villages and stealing livestock as they went his army marched south to capture the town of Caen before then following the line of the River Seine towards Paris but with all the bridges destroyed there was nowhere to cross. Paris had in any case been both fortified and reinforced and there was no prospect of the English besieging it.

In the meantime, disease, exhaustion and desertion were taking their toll on Edward’s army and although he had met little more than local resistance during his advance King Philip had mined a deep hatred of the English to rally the French nobility to his cause. So with a fortified Paris to his front and a powerful army fast approaching Edward who saw clearly the danger he was in chose not to give battle but instead ordered a retreat, to the coast if he could.

The order was not given too soon, the French were closing in and there was a serious prospect of Edward’s army finding, itself trapped with its back to the river Somme. He had to find a crossing and quickly. A reward was offered to any man who could indicate where a crossing could be made; an obliging peasant was found who guided them to Blanchetaque, a tidal ford that could only be crossed at certain times of the day. Its opposite bank was also heavily defended by some 4,000 French troops. But time was of the essence and Edward did not hesitate to order a forced crossing. The English prevailed after a fierce and bloody struggle, but the time lost ensured that there was no longer any prospect of them reaching the coast and possible embarkation before the French Army caught up with them – he would have to give battle, after all.

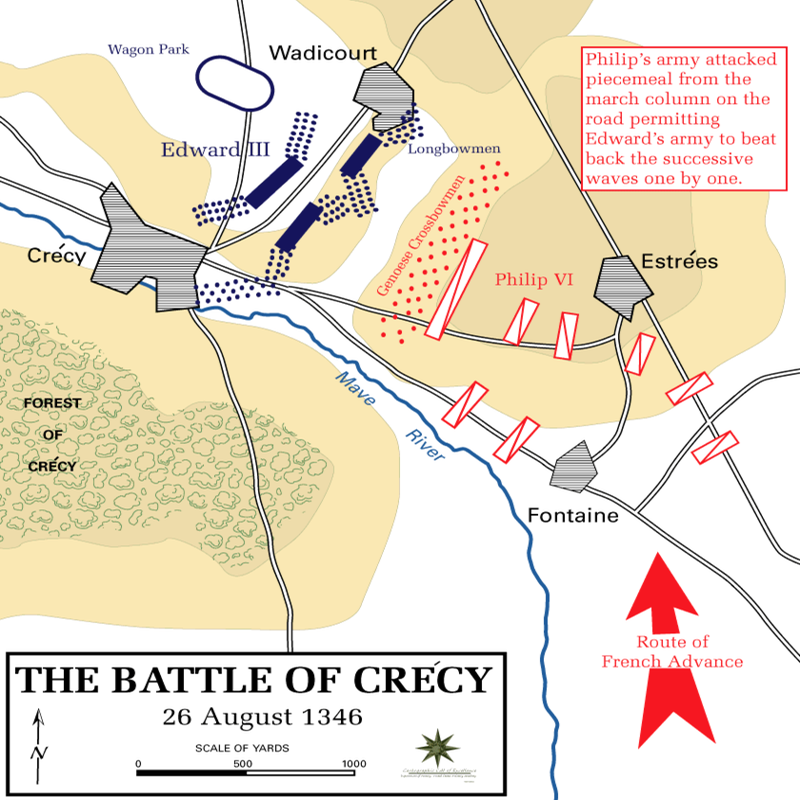

After carefully reconnoitring the ground Edward made camp between the villages of Crecy and Wadicourt some ten miles from Philip’s army camped at Abbeville. Although the ground provided little obvious topographical advantage Edward had chosen his position well, it was in effect a clearing surrounded by woods with the shallow River Maye protecting his right flank. Any attack would have to be a frontal one over undulating ground and under heavy skies.

The atmosphere in the English camp on the eve of battle was tense but calm. Edward held a Council of War before accompanied by his son also Edward, the Prince of Wales, he attended Holy Communion. In the meantime, his soldiers busied themselves polishing and sharpening their weapons while also saying their prayers and receiving confession.

Edward could muster only around 11,000 troops barely a tenth of those available to his enemy and so he prayed to God for deliverance from overwhelming odds. Divine intervention may have been sought but he was under no illusions that the fighting would have to be done by men.

The night before the battle the English King addressed his little army. In his History of the English-Speaking People Winston Churchill described the scene:

“Mounted upon a small palfrey, with a white wand in his hand, with his splendid surcoat of crimson and gold over his armour, he rode along the ranks encouraging and entreating the army that they would guard his honour and defend his right.”

With their spirits raised his troops settled down to a restless night.

Ten miles away in the French camp confidence of victory remained high. King Philip took mass in the nearby Abbey before reviewing the vast army that stretched out before him with troops it seemed still arriving from all directions. He loathed the English and was eager to engage them particularly as they were already arrayed and ready for battle. Instead, he erred on the side of caution. His army had yet to fully gather and so the order was given to halt and regroup while those columns still advancing on Crecy caught up. He would fight on the morrow - but the French blood was up.

It was customary for the Constable of France to command the French King’s army in battle, but the Count Eu had been captured earlier in the campaign. They would miss his experience and even more so his presence for with no one to lead them it fell to any number of Dukes and Counts to assume an authority they did not possess. In competition with each other for the honour and glory of victory little could now be done to slow the momentum to battle.

It was a clear, crisp day, the ground was dry, and the early morning mist had long cleared though the clouds overhead were thick and many. Edward had formed his army into three divisions with the right flank commanded by his son the seventeen year old Prince of Wales ably assisted by the Earl of Oxford and Sir John Chandos among others; the left flank was led by the Earl of Northampton while to their rear was the Reserve Division commanded by the King in person who did so from an elevated position atop a windmill from where he could get a better view of proceedings.

The English then were well prepared with long jagged lines of archer’s longbows at the ready behind stakes rammed into the ground for their protection, the knights and men-at-arms dismounted their swords and armour glinting in the sun stood ready for the fight, while behind them were the spearmen prepared to kill for profit and strip the corpses of their victims.

It was already afternoon by the time Philip ordered his 15,000 Genoese crossbowmen, mercenaries who were considered the best in Europe, to “Go before and begin the battle in the name of God and Saint Denis,” but weary from an overnight march and weak with hunger they complained bitterly “We be not well ordered to fight this day. We are not prepared to do any great deed of arms. We have more need of rest.” Their complaints were not well received, the Duc de Alencon remarked, “to be charged with such rascals, to be faint and fail now at most need.”

The Genoese would have to get within 200 yards of the English for their bolts to be truly effective while they could only fire once every two minutes. The longbow in the hands of a skilled archer could fire 12 arrows every sixty seconds. The Genoese knew this and were frightened.

As the Genoese began their advance thunder rent the air, the storm clouds broke, and the rain, came sheeting down. The storm was brief but for those of a superstitious nature it was both ominous and forbidding.

The Genoese advanced with little enthusiasm and many fired too soon, their bolts falling short. As they knelt to reload the English response was swift and deadly, taking a pace forward and aiming their longbows skywards so their arrows would descend in an arc they, (as the French chronicler Froissart described) “let fly their arrows together and so thick it seemed like snow.” They took a terrible toll, the Genoese some cutting the strings of their bows before they did so, broke and fled.

Upon witnessing their flight, a furious Philip ordered his knights to ride them down and “slay the rascals.” They needed little encouragement riding through and over them cutting them down with sword and lance. But the flower of French nobility would fare no better than the Genoese they now scorned as the arrows continued to fall thick and fast, an incessant hailstorm of death that pierced helmets and chainmail and laid low the horses in their hundreds and thousands. Some were hit multiple times while others reared up in pain and careered over the battlefield. They were sowing chaos and confusion but still more knights joined the fray.

As dismounted knights in heavy armour struggled to their feet on ground softened by rain and churned up by horse’s hooves they were set upon by the English men-at-arms emerging from the ranks to strike them down with axe, knife, and sword while others trampled underfoot suffocated in the mud. It was an assault so ferocious that many a rich ransom was lost that day. Yet still the French knights charged wave after wave of them.

One of those eager to engage was Philip’s close ally the blind King John of Bohemia who ordered his attendants to take the bridle of his horse and lead him to where the fighting was at is fiercest so he could strike a blow against the loathsome English. But he was soon dragged from his horse and butchered, his corpse found alongside those of his men.

But it wasn’t the armoured knights upon their impressive steeds who would threaten to snatch victory from the jaws of defeat but infantry from Germany and Savoy who now pressed down hard up the English right flank where they had broken through the line of archers and were engaged in heavy hand-to-hand fighting that was described by a contemporary as, “murderous, without pity, cruel, and very horrible,” as the wounded their helmets removed were knifed, clubbed to death, or had their throats cut.

The young Prince of Wales was in the thick of it, but the pressure was beginning to tell, and it seemed for a moment as if the enemy would overwhelm them. A knight, Sir Thomas of Norwich was despatched to beg the King for help but once informed that his son was neither dead nor incapacitated, he refused exclaiming: “Let the boy win his spurs, for if God has so ordained it, I wish the day to be his and the honour to go to him, and to those in whose charge I have placed him.”

The right flank would hold, and the Prince of Wales battered, bruised but otherwise unharmed and unbowed would emerge triumphant though the King did yield a little and send 30 knights to his assistance; but with fresh troops still arriving on the battlefield the attacks continued and with no less ferocity than before though the outcome remained the same with the English advancing a little to finish off the fallen before withdrawing once more to regroup and resist the next attack. It was only night that brought the fighting to an end as the French King with barely sixty knights remaining, his horse shot from under him and wounded by an arrow to the shoulder was at last led from the field of battle.

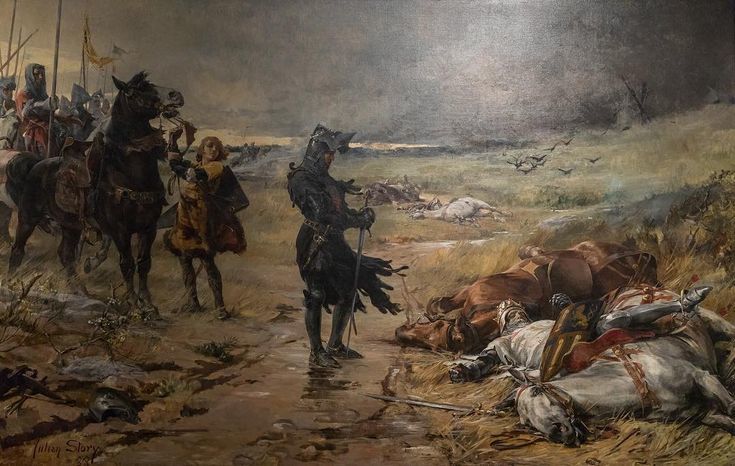

The English lit bonfires that night in celebration of their triumph, they sang songs and taunted their enemy, but they also gave thanks to God. In the meantime, King Edward who had observed the events of the day from the relative safety of the windmill and had remained calm throughout now made his way to the Prince of Wales and where the fighting had been at its fiercest and most prolonged. Embracing his young son the King told him, “You are my son, for most loyally have you acquitted yourself this day. You are worthy to be sovereign. God give you good perseverance, sweet son.” The prince, soon to be known as the ‘Black Prince’ for the colour of his armour humbled himself before his father giving all honour to him.

It had been a long, hard fought battle and skirmishing continued until well after midnight, and casualties had been high. The English had lost some 400 men killed mostly from among those who had been fighting with the Black Prince. French casualties had been devastating however, with 1,542 knights, the flower of the French nobility (among them not just King John of Bohemia but the Duc d’Alencon and the Count of Bloise) left dead on the battlefield along with 15,000 others of all ranks – and there was still more to come.

The following morning Edward despatched 3,000 men to reconnoitre the surrounding

countryside where they encountered numerous detachments of French infantry many of them untrained levies unaware of the battle just fought. Expecting the troops approaching them to be friendly they were unprepared for the ferocity of the English attack. Time and again they fled and were cut down in their thousands by an enemy no longer inclined towards mercy. Some have suggested that as many Frenchmen were killed in its immediate aftermath as died in the battle itself.

While the Battle of Crecy remains one of the great feats of English arms its consequences were not so triumphant. His army was depleted and exhausted and without the resources to properly exploit his victory Edward’s audacious plan to depose Philip VI and seize the French crown failed; so, his retreat towards the coast continued where he laid siege to Calais. Regardless of the glory accrued from Crecy he did not want to return to England without some tangible gain, but Calais would not fall for another eleven months during which time starvation and disease ravaged the English camp. Meanwhile, the Parliament in London that had been reluctant to finance his campaign in the first place now dragged their heels when it came to reinforcement and resupply.

The capture of Calais which would maintain and English presence on the French mainland for the next two hundred years and provide a port of entry for future conflicts was nonetheless poor reward for a victory of such magnitude; while any sense of triumphalism would soon be forgotten as both European Continent and the British Isles were convulsed by a killer far deadlier than the Welsh longbow – the Black Death.

Tagged as: Ancient & Medieval, War

Share this post: