Battle of Flodden Field

Posted on 4th April 2022

On 13 June 1513, King Henry VIII invaded France - eager for war and the opportunity to emulate his great hero and namesake Henry V, the victor at Agincourt, he had earlier joined England to the anti-French Catholic League created by Pope Julius II who had also in turn urged him to renew his claim to the French crown. Henry needed little encouragement but by doing so he would challenge less for the French throne than he would imperil his own for it was not France that posed a threat but an enemy closer to home - the Scots – who through their resumption of the Auld Alliance were obliged to and would, invade England from the north.

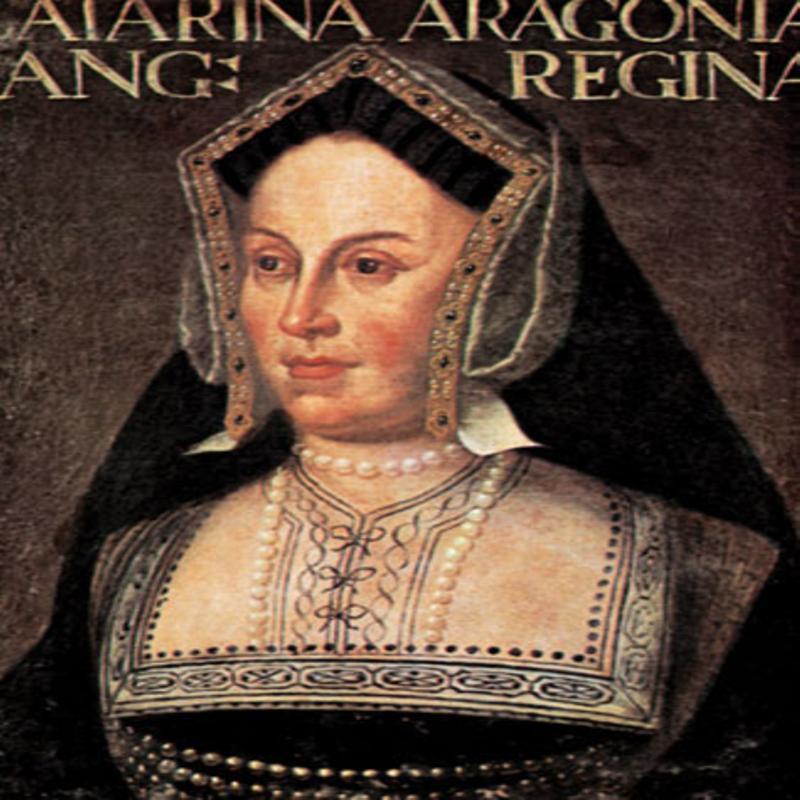

England in Henry’s absence would be governed by his Queen, Katherine of Aragon, six years his senior and a woman he trusted to keep his realm safe, a responsibility she was at ease with - my heart is very good to it. Nonetheless, aware of the threat posed by the Scots before his departure he appointed Thomas Howard the Earl of Surrey, an experienced soldier to be her military commander.

Scotland’s King James IV had inherited the throne following a coup that had resulted in the death of his father, a betrayal that weighed heavy on his shoulders. Like his brother-in-law the English King, he had married Henry’s older sister Margaret Tudor in 1503, he believed in the chivalric code but whereas Henry sought to emulate a predecessor James wished to wipe clean his earlier betrayal. A resumption of the Auld Alliance would provide him with the opportunity to do so and the French were certainly eager that he should. So, a fleet was despatched carrying arms and gunpowder along with a gift of 14,000 crowns and a personal letter from Queen Anne of Brittany imploring James to be a “true knight and invade England.” His Queen thought otherwise and beseeched James to keep the peace. When he remained firm in his view that the terms of the Auld Alliance must be honoured, she asked, “Why do you prefer the Queen of France to me your wife and mother of your children?” And she was not alone in her opposition there were others also counselling caution, but James remained adamant.

In August, James gathered his forces in Edinburgh, some 40,000 men from across Scotland including the Isles and the Highland Clans having earlier, in accordance with his understanding of chivalry, written to Henry to inform him of his intention to invade northern England should he not withdraw his army from France. Receiving no reply on 22 August the Scottish Army crossed the River Tweed into England.

Progress would be slow however, as James wasted time capturing a series of small towns and castles of little strategic value or significance. Indeed, his army was still in Northumberland when it was confronted by that of the Earl of Surrey which had hurried north on the orders of Queen Katherine.

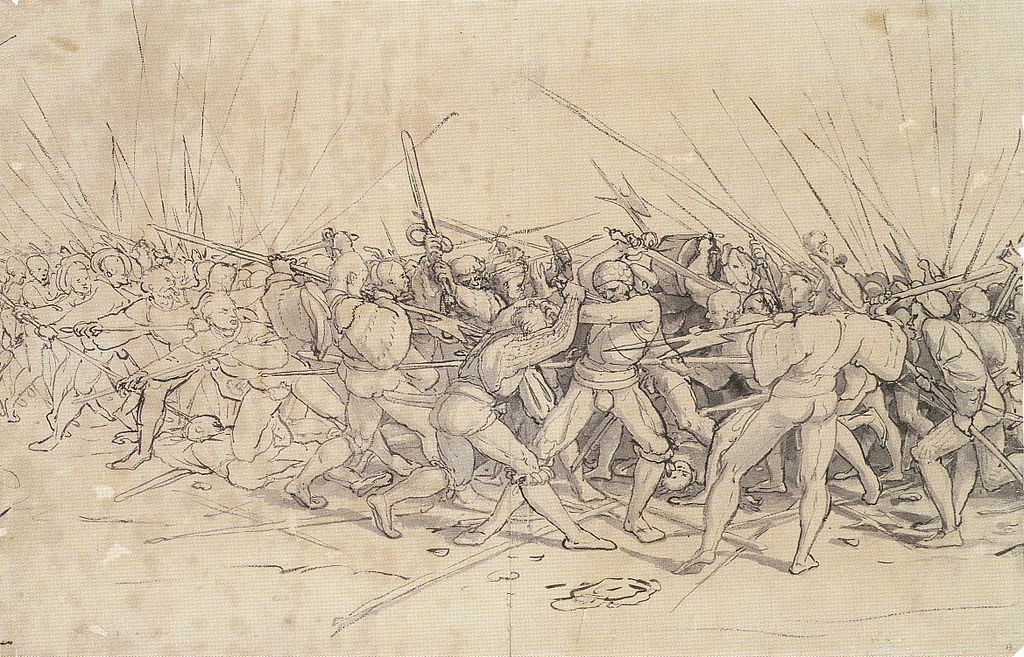

The Scottish was the larger of the two armies by some 10,000 men while both had around 30 cannons of a rudimentary kind but difficult to manoeuvre and better suited to siege warfare, they were to prove largely ineffective on the field of battle. Also, James had recently introduced the long pike as his principal infantry weapon. It had been utilised to great effect on the Continent when used in phalanx, but such deployment required a great deal of training while the pike itself at 15 feet long was both heavy and unwieldy and of little use in close quarter combat.

The English by comparison had a large contingent of cavalry and men-at-arms but their primary strike force remained as usual the many archers and long-bowmen they had in their ranks.

On 3 September, the Earl of Surrey sent a letter to James IV requesting their respective armies meet on the field of battle; to agree to such a request would be the chivalrous thing to do and James was anxious to grasp the nettle or so he told his advisers, but he was no fool. Perhaps, the recent misfortune endured by Lord Home when he led 7,000 Scottish Reivers to plunder the villages thereabout only to be ambushed and set to flight by a force of English archers leaving a great many dead behind them had cautioned him to adopt a more defensive posture, for now at least.

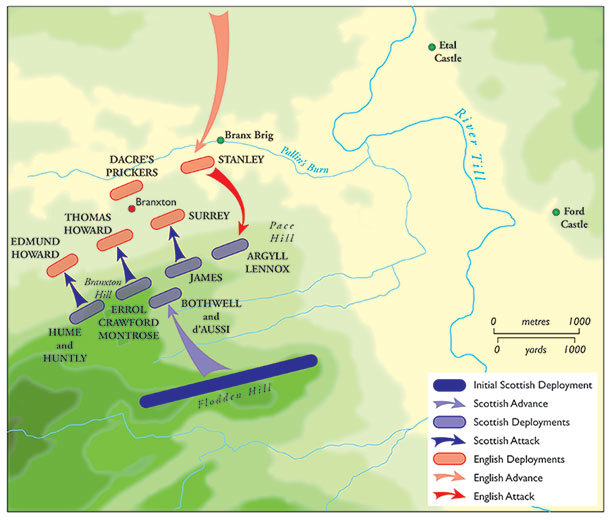

In England, Katherine of Aragon was busy raising an army of 60,000 men which she intended to march to York thereby barring the way to London should any misfortune befall the English Northern Army. The Earl of Surrey knew that he had a fall-back position then, should things not go according to plan. In the meantime, he sought to coax the Scots from their encampment at Flodden Edge by manoeuvring around their flanks, but James would not be drawn. Instead, he withdrew his army to an even better defensive position on Branxton Hill which flanked on either side by marshland could not be so threatened.

To ford the River Till, the Earl of Surrey now split his army into two. He found several places to do so downriver while he sent his son, also Thomas Howard, in command of the vanguard to cross via the Twizell Bridge. As they advanced however, they stumbled into the entire Scottish Army still camped on Branxton Hill. Heavily outnumbered any encounter now could have ended disastrously. While Howard did his best to shield his meagre force from the prying eyes of the Scots on the high ground, he sent frantic messages to his father for support. He needn’t have worried for despite being advised to do so James declined to attack declaring it dishonourable to do so and that when he defeated the English Army it would be in its entirety.

As the English Army closed in the Scots remained on Branxton Hill determined it seemed to defend the high ground they occupied. By the morning of 9 September, the battle lines were drawn but the fighting did not actually begin until late afternoon when the cannon of both sides engaged in a somewhat perfunctory and ineffectual artillery duel; far more impactful was the hailstorm of arrows that the English long-bowmen now rained down upon the Scottish formations. It was perhaps the toll they were taking that convinced James to begin a cautious advance, still in-formation thereby maximising the effectiveness of his pikemen, downhill towards the English lines. It would prove not only a rash but a fateful decision.

Yet it began promisingly enough, the left flank commanded by Lord’s Hume and Huntly raced ahead of the rest of the army with Huntly’s Highlanders particularly eager to engage. Armed with their traditional claymores they charged into the English lines with such ferocity that they didn’t just break but were soon fleeing for their lives.

Witnessing the success of his Highlanders convinced James to order an all-out advance including most of his reserves. It would prove poor timing for Huntly either unable or unwilling to maintain discipline did not order his troops to re-join the attack but left them to loot the bodies of the dead.

James had blundered and done so disastrously, with the ground soft underfoot and weighed down by the pikes they were carrying the attack slowed and any momentum gained from advancing downhill was soon lost. He was also unaware that in front of his army lay a bog which rendered any mobility a mute issue. Unable to manoeuvre the Scottish formations began to break apart – they were quite literally stuck in the mud. Observing the Scots in disarray the Earl of Surrey ordered his infantry to advance.

With their formations broken the Scots now found their pikes to be worse than useless as the English swarmed among them cutting them down in huge numbers – Flodden Field had become a killing field.

As the fighting intensified King James dismounted from his horse to stand alongside his men. Those in his entourage did likewise while other nobles also followed his example.

The failure of Huntly’s along with many of Lord Home’s troops to return to the battlefield had left the Scottish left flank exposed. The void would be filled by Lord Dacre’s English cavalry who were able to manoeuvre around the flank virtually unopposed to attack the Scottish Army from the rear. Two hours of fierce hand-to-hand fighting followed but the outcome was no longer in doubt. It was now in the forced melee of an unequal struggle the King James was killed along with so many of his nobles. Seeing their King dead on the field those Scots not yet engaged hastily withdrew while others threw down their arms and fled – the Battle of Flodden was over.

Just the previous month Henry VIII had been victorious at a brief but bloody skirmish that had seen the French cavalry flee with such haste it became known as the Battle of the Spurs. He revelled in the moment, but it paled into insignificance when placed alongside that achieved by his Queen and her General the Earl of Surrey. They had destroyed an entire army and humbled a nation.

Not only had the Scottish King been killed but the flower of its nobility and religious establishment had also lost their lives on Flodden Field:

The Archbishop of St Andrews, the Bishop of Caithness and the Isles, the Grand Prior of the Knights of St John, the Dean of Glasgow, the Abbot of Inchaffray, the Abbot of Kilwining (Lord High Treasurer):

The Earls of Bothwell, Caithness, Cassils, Crawford, Errol (Lord High Constable), Lennox, Montrose, Morton, and Rothes:

Lords Avondale, Borthwick, Elphinstone, Erskine, Innermeath, Maxwell, Ross, Seton, Sempill, and Sinclair:

Some 115 others of noble rank were also killed Knights and various Clan Chieftains. Alongside them 10,000 ordinary Scots also died.

The English had lost around 1,500 men killed.

Henry VIII had gone to war in France seeking glory only to see it achieved at home in his absence. Katherine was not insensitive to this and so she wrote to Henry a letter and with it sent a piece of the Scottish King’s bloodstained coat retrieved from his body: “You see I can keep my promise, to send for your banners a King’s coat. I thought to send himself to you, but our Englishmen’s hearts would not suffer it.”

But the victory she made clear belonged to him provided in his absence by the “valour of his subjects and God’s good grace.”

It was then the greatest honour and as if he had been there in person: “And with this I make an end, praying God to send you home shortly for without that no joy can be accomplished.”

Tagged as: Tudor & Stuart, War

Share this post: