Battle of Omdurman: Blood in the Sand

Posted on 6th March 2023

On the morning of 26 January 1885, after 319 days of siege the city of Khartoum in the Sudan fell to the forces of Muhammad Ahmed, the self-proclaimed Mahdi, or Expected One. The garrisons Commander General George Gordon had been speared and hacked to death on the steps of the Governors Palace his severed head carried off in triumph to the enemy camp where a displeased Mahdi, who had ordered that the English Pasha be spared such indignities responded angrily: “What is this? What deeds are these, why do you disobey me, why have you mutilated him? What use is it?”

His apparent respect for his enemy did not extend to the dignified repose of his corpse for the head he ordered hung between trees to be pecked at by crows and looked upon with disdain by children. What else remained of him he had thrown down a well.

The Sudan, still nominally under the control of Egypt, had been cleared of the Infidel but the Mahdi’s dream of spreading his Wahhabi influenced brand of fundamentalist Islam to the rest of the Muslim world would go unrealised for he too would die, suddenly and unexpectedly just six months after the moment of his greatest triumph.

The Mahdi was succeeded by his long-time ally Abdullah ibn Muhammad, also known as Muhammad al-Taashi who took the title of Khalifa, but he was not the ‘Expected One’ neither was he entirely trusted being seen as a man of ambition and pride who wished to make himself a King.

His assumption of power did not go unopposed, and he was to spend many years establishing his authority maintaining the strict Sharia law that had been imposed by his predecessor and a large army with which to enforce it. Aware that he was not the Mahdi and did not command the same respect he would use war as a means of diverting criticism of his rule. In 1887, he invaded neighbouring Ethiopia singling out the Christian population for particularly harsh treatment destroying Churches and massacring thousands, but for all his brutality and a series of victories that culminated in the death of the Emperor Yohannes IV at the Battle of Metemma, by 1889 he had withdrawn back to Khartoum.

If he had ever truly shared the Mahdi’s vision of imposing Wahhabism on the entire Islamic world, and many doubted his sincerity, then it had stalled in the desert wastes of the Sudan. Even so, al-Taashi’s evident belligerence and the fervent religious fundamentalism of the Ansar Movement he led posed a constant threat to Egypt and thereby Britain’s control of the Suez Canal, its lifeline to the East; but it would not be the shifting sands of Islamic rivalry or the yearning to avenge Gordon that would see the wrath of the British Empire once more descend upon the Sudan but the ambitions and frailties of its Imperial competitors in the Scramble for Africa.

But Africa was not just the geographical expression of Imperial aggrandisement but also a convenient place for the making of ersatz conflicts and the fighting of proxy wars, an opportunity for the bellicose flexing of muscles far away from the political tinderbox of Europe that could spark a far greater conflict as happened in 1914 with catastrophic consequences.

On 1 March 1896, an Italian attempt to annexe Ethiopia ended disastrously when its army was annihilated at the Battle of Adowa. Political hubris had led to national humiliation, but worse it had shown to those seeking to do so that the Western Powers could be successfully resisted. The Italian defeat had also left their possessions in the Horn of Africa and elsewhere vulnerable to incursion, and it was this coupled with French encroachment into the Upper reaches of the Nile Delta, that now threatened British hegemony in Egypt.

The presence of a British Army in the Sudan had once again revived the campaign to avenge Gordon. The passage of time had done little to diminish his status in the public imagination as the quintessential Englishman, a Victorian Christian hero who had given his life in the service of God and the Empire. As far as the public and the popular press were concerned the New Mahdi was much the same as the Old Mahdi and they were both the Mad Mahdi indistinguishable in their savagery and barbarism.

Lord Salisbury’s Government needed little encouragement to undertake a campaign of retribution and General Kitchener would soon receive his orders for the re-conquest of the Sudan.

Although his army had been heavily reinforced Kitchener could only muster around half or even fewer the number of fighting men available to the Khalifa but his 8,200 British Regulars among them the Seaforth and Cameron Highlanders along with 17,600 Egyptian and Sudanese troops were well-armed and well-prepared.

The British troops were armed with the new Lee-Metford bolt action magazine rifle, and some units had been provided with the recently developed hollowed out Dum Dum bullet designed to cause maximum damage which would be banned at the Hague Convention of 1899.

Although they had been trained by and were led by British Officers the Egyptian troops along with their Sudanese allies were still not thought entirely reliable and so were armed with the old single-shot Martini-Henry rifle; but then they were expected to play a subordinate role, though this would not be the case at Omdurman.

There was also the Camel Corps and a sole Cavalry Regiment the 21st Lancers.

Four River Gunboats had also been built in Britain and despatched to Egypt in pack form to be reconstructed upon arrival increasing his number of Steamers to ten armed with 36 cannon and 24 machine guns in total.

The 21st Lancers would achieve lasting fame at Omdurman and among their number would be the young Lieutenant Winston Churchill of the 4th Hussars then stationed in India.

Churchill was desperate to see action and participate in the Sudan campaign but his attempts to obtain a transfer or secondment to the 21st Lancers despite frequent telegrams and intensive lobbying on his behalf by friends and colleagues alike, were ignored by Kitchener who had no time for jingo Officers especially those who wished to write of their experiences, and Churchill had just published his book The Malakand Field Force. The Sirdar was not impressed. It was only when Sir Evelyn Wood who had the authority to appoint Officers to the Regiment overruled Kitchener that Churchill at last got his wish, but even now he would have to wait for a fellow Officer to signal his inability to participate. Kitchener’s ire only increased when just prior to his embarkation for the Sudan Churchill received the commission as War Correspondent for the Morning Post.

As dissatisfied as he often was with 25,000 men under his command, 44 artillery pieces and 20 Maxim Machine Guns supported by Gunboats Kitchener was confident of victory. It was after all the best equipped army ever to undertake a desert campaign.

The large Dervish Army was a seething mass of 60,000 fierce, experienced warrior tribesmen armed with spear, club, and sword along with the many firearms they had captured from their Egyptian enemy. And they were a sight to behold, dressed in white tunics with black patches on their chest with an array of flags in a multitude of colours, green, black, red, and white embroidered with quotes from the Koran, the razor-sharp tips of their swords and spears glinting in the desert sun. The coming conflict was for them Jihad, or Holy War, and fired by religious zeal they would fight and die for Allah against the Infidel it being said that their desire for death was greater than their lust for life.

Adhering rigidly to the course of the Nile where he could be supplied and supported by his steamers and gunboats Kitchener’s progress was slow much to the frustration of the Government in Westminster which sought a swift conclusion to the campaign. A frustration that only increased further when an overwhelming victory at the Battle of Atbara in early April did not speed up the momentum.

If Government Ministers were muttering dissatisfaction under their breath, then Kitchener cared little for it, he knew that inconclusive victories become mere footnotes of history whereas defeats are rarely forgotten. If it was not in the Sirdar’s character to act in haste, then it was not in the Khalifa’s interests to compel him to do so.

He may have wished to lure Kitchener’s Army into the desert wilderness as the Mahdi had done to General Hicks at El-Obeid with such catastrophic consequences for his Egyptian Army fifteen years earlier; but the Sirdar could not be tempted by the prospect of battlefield heroics so instead his advance was closely monitored and his patrols harassed while communications could often be seen flashing across the desert plain, The Sudan is vast in its expanse and there was no need for confrontation - time is less precious in a timeless place, and Allah would provide.

As August passed into September the Sirdar’s Army reached Kerreri just seven miles short of the Khalifa’s capital at Omdurman where they dug-in and awaited the inevitable attack.

Military convention declared it unwise to position an army with its back to a natural obstacle that prevented the opportunity to retreat in adversity, but Kitchener did so before the river Nile so he could be supported by the gunboats thereby maximising his firepower. There the army prepared for battle behind the Zariba, a series of shallow trenches protected by a thorn thicket fence. Before them was a wide open plain almost devoid of cover with hills either side that loomed large in the barren landscape and did offer the opportunity for concealment.

Kitchener despatched his cavalry to reconnoitre the terrain and drive any Dervish from nearby hills, but the enemy were closer than was at first thought and they soon withdrew back to the Zariba.

The Dervish Army was moving fast, as in five great columns they advanced on a front four miles long with a force that appeared to make the ground shake. Many of them were from the feared Haddendowa Tribe known to the British soldier as the Fuzzy-Wuzzy for their distinctive hair.

An attack seemed imminent as in the Zariba bugles sounded the call to arms, but the Dervish stopped short of doing so and instead with a great roar that seemed to echo off the hillsides made camp, their distant flags fluttering in the light breeze.

Battle would be delayed for the time being then, and as darkness descended searchlights from the steamers on the Nile swept the desert plain making for an eerie sight as both camps settled down for a nervous if not quiet night.

In the meantime, Kitchener had sent gunboats down the river to bombard Omdurman with their howitzers and silence its guns which after a short but ferocious exchange of artillery fire they succeeded in doing.

The Khalifa had intended to prevent the Sirdar from using his gunboats to such good effect by mining the approaches to both Omdurman and Khartoum, but the experiment was abandoned when the Egyptian engineer who had been released from prison on condition that he assist in the defence was killed when the boat he was working from blew up.

At 05.50 on 2 September 1898, with his men already at their posts, having ordered his cavalry back into the hills, and with the gunboats ready to support the vulnerable flanks of his army, General Kitchener surrounded by his Staff Officers heard the banging of drums, the blowing of horns, and the barely distinguishable cries of Allahu Akbar on the still, hot air – the Dervish Army was advancing.

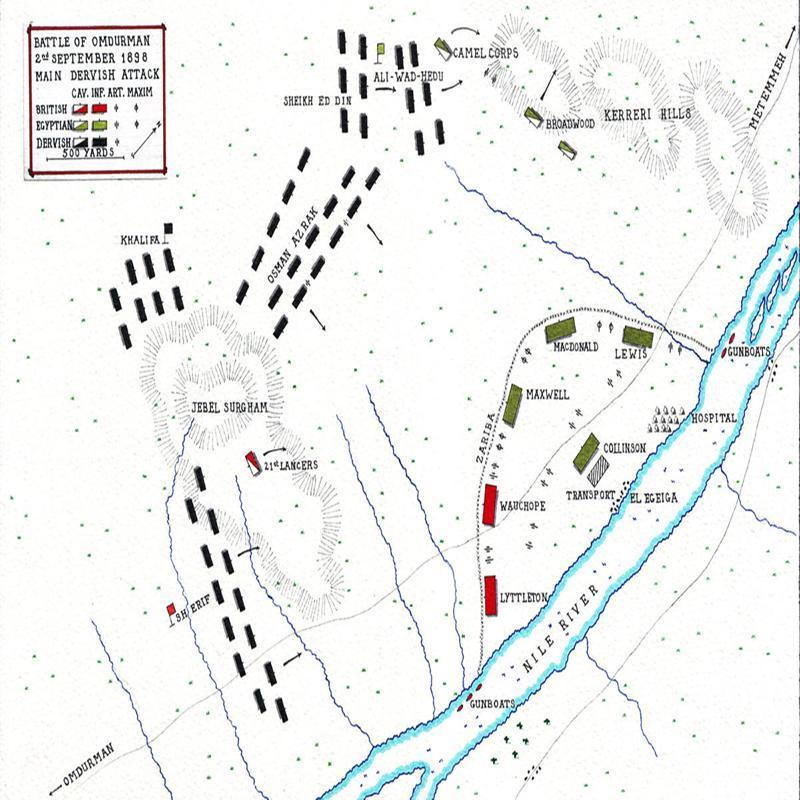

The Khalifa’s plan was a simple one - he would overwhelm the Infidel by sheer weight of numbers with the ferocity of the attack sweeping the enemy into the Nile from where there could be no escape. As such, he ordered his trusted subordinate Osman Azrek with two Corps, around 16,000 men, to advance across the open plain and assault the centre of the Allied line whilst simultaneous attacks would be made on both flanks. In the meantime, he would wait in reserve with a similar number of men concealed behind hills and in the folds of the ground ready to exploit the weaknesses exposed as the enemy crumbled before the Will of Allah. Should the slaughter of the Infidel not prove to be the Will of Allah then he had an alternative plan in mind, but this had already been second-guessed by the Sirdar.

The Khalifa’s guns fired first but fell short of the Zariba kicking up dust but little else. They did, however, cause the Allied artillery to retaliate and to far greater effect as opening fire at some 3,000 yards distance while the Dervish Army remained but dots in the desert the shells tore into their ranks reaping a terrible harvest long before they even came within range of machine gun and rifle fire.

But the Dervish were advancing fast particularly into the hills with the 21st Lancers forced to beat a hasty retreat to the Zariba whilst the Camel Corps in the Kerreri Hills were forced to dismount and engage in hand-to-hand combat, only saved from annihilation by supporting fire from the gunboats positioned on the right of the line.

In the centre, the Dervish came on through the torrent of shot and shell and into a withering wall of fire that saw them disappear in a cloud of gun-smoke and dust. Few were to get within 350 yards of the Zariba with those armed with rifles lying down to exchange fire while others exhausted and terrified sat upon the ground and merely prayed. Unable to close with the Infidel they withdrew in disarray leaving behind more than 4,000 dead and wounded among them Osman Azrek, himself.

On either flank the Dervish attacks were likewise bloodily repulsed unable to sustain their momentum against the pounding of the howitzers and relentless rat-tat-tat of the Maxim guns coming from the boats.

A lull in the fighting followed the Dervish retreat and the devastating impact of Allied firepower on their massed ranks now prompted Kitchener to take a bold decision – he would order his army to advance concerned that the Khalifa might withdraw to Omdurman or Khartoum and fight for them street by street, something he wished to avoid; neither did he wish to engage in a siege which would negate his superiority in arms and so he determined to place his army between the Khalifa and his capital forcing him to flee west into the desert.

His decision was opposed by many on his Staff who thought it premature arguing that the Dervish Army was still intact, indeed many had not yet even been engaged, and that to advance now would be to lose the support of the gunboats moored on the river and expose the army to possible encirclement. But Kitchener’s worst fears seemed realised when reports reached him that large numbers of Dervish had been seen marching in the direction of Omdurman.

The 21st Lancers were sent to reconnoitre the Jebel Surgham and locate the main body of the Khalifa’s Army; this they could not do but they did signal to confirm the earlier reports. A little later they received the order: “Advance and clear the left flank and use every effort to prevent the enemy re-entering Omdurman.”

Commanding the 21st Lancers Lieutenant-Colonel Martin took the order to mean that he was to engage the enemy where he found them, something he was eager to do, so when he received the news that some 700 Dervishes had been observed sheltering in a Khor, or hollow in the ground, on the road to Omdurman he determined to attack them.

Whether they had been deliberately reinforced in the meantime or the initial report had been misleading the actual number of Dervishes present was nearer 2,500.

The Officers of the 21st Lancers were desperate to win the Regiment its first battle honours and Lt-Colonel Martin determined to do so in the grand style by dispersing the enemy in a classic cavalry charge with lances lowered and swords drawn.

Lt Winston Churchill, commanding a troop, sheathed his sword trusting instead to the Mauser pistol he had purchased in London prior to his departure for the Sudan.

Advancing slowly at first wheeling left and right to avoid groups of Dervishes who stood in their path they began to pick up the pace as they neared their destination until at 250 yards distant the bugles were blown to sound the charge. Whether by this time or not Lt-Colonel Martin had realised it he was in fact leading his 350 men into an ambush and as they swept down the side of the Khor they did so into a solid mass of humanity as Dervish tribesmen seemed to appear from nowhere.

Churchill later described the scene:

“A deep crease in the ground – a dry watercourse, a khor – appeared where all had seemed smooth, level plain, and from it there sprang, with the suddenness of a pantomime effect and a high-pitched yell, a dense white mass of men nearly as long as our front and about twelve deep. A score of horsemen and a dozen bright flags rose as if by magic from the earth.”

Surrounded with their horses speared and slashed, hands reaching up to pull them from the saddle, the Lancers maintained enough momentum to cut their way through but at a cost, 109 horses lost, 20 men killed, and a further 50 wounded.

Had the charge stalled it would have ended in a massacre and now free of the melee Lt-Colonel Martin wasn’t about to repeat the mistake, he ordered his men to dismount and engage the enemy using their carbines who under fire and unable to respond simply melted away.

At 09.15 the Allied Army marching in line with the British Brigades in the vanguard moved out from the Zariba heading west towards the Jebel Surgham Ridge from where they hoped to sever the Khalifa’s line of retreat.

The advance was covered, though from some distance, by the gunboats on the Nile as they moved towards Omdurman whilst the artillery and Maxim guns had been distributed throughout the Column to provide added protection on the open plain.

Kitchener had guessed correctly that the Khalifa intended to withdraw to Omdurman and fight a defensive battle but by advancing while still unaware aware of the disposition of his enemy’s forces he had exposed his flanks to attack and left the rear-guard vulnerable to being separated from the rest of the Column and systematically destroyed.

The Sirdar in his haste had provided the Khalifa with an opportunity he had not expected and one he was determined to seize.

Despite the bloody repulse of earlier in the day he still had some 40,000 men at his disposal, 20,000 in the Kerreri Hills to the east and rear of the Allied Column including fast-moving Baggara Horsemen and his own elite bodyguard the Black Flag concealed behind the Jebel Surgham - and it would be with these and the blessing of Allah that he would annihilate the Infidel.

As the advance units of the Column began to scale the Jebel Surgham, they encountered the 21st Lancers still holding their position and tending to their wounded (many of whom had deep and disfiguring cuts to their legs, arms, and faces) who with the adrenaline still pumping through their veins were eager to make their report and talk of their exploits. General Kitchener was unimpressed disappointed that they had failed in their mission to locate the main body of the Dervish Army.

Bringing up the rear of the Column were the 3,500 men of Colonel Hector MacDonald’s mostly Sudanese Brigade who found themselves particularly vulnerable to attack from the tribesmen massed in the Kerreri Hills and so had been provided with 8 cannon and 3 Maxim guns as a precaution, they would prove an invaluable reinforcement as the Column became increasingly stretched, gaps appeared in the line, and their position became ever more exposed.

The Sudanese contingent of the Sirdar’s Army also drew the ire of their tribal brethren for whom they were not only traitors but apostates who had abandoned the One True Faith and so were primed for death.

As the Sirdar prepared to storm the Jebel Surgham Ridge and expel the Dervish there, MacDonald could already be seen deploying his troops for what he thought was the threat of imminent attack – he was right. Out from behind the Jebel Surgham stormed the 15,000 men of the Black Flag, the finest warriors in the Dervish Army led by Yakub, the Khalifa’s most trusted commander.

Sweeping past and beyond other Allied units on their flanks the Black Flag headed straight for MacDonald’s Brigade still deploying frantically to meet the threat. As they did so the Sirdar’s troops who had since captured the Jebel Surgham Ridge were ordered to fire down upon the Black Flag as they advanced forcing the Khalifa to divert men from the main thrust of the attack to try and re-take the heights.

It was a forlorn hope they might do so and charging uphill into a hail of gunfire they were cut to pieces.

The Black Flag fared little better in their attack upon the rear-guards right flank for despite an effective range of only 400 yards and a maximum rate of fire of 12 rounds per minute, which few could achieve, the massed ranks of the Martini-Henry armed Sudanese and Egyptian troops of MacDonald’s Brigade took a terrible toll of the attacking Dervish who began to break up and fall away long before they could even get close to the hand-to-hand fighting they so desperately sought. But any respite for MacDonald’s men would be brief.

As the Black Flag began to flee the field Ali-Wad-Helu led his 20,000 tribesmen from the Kerreri Hills to attack from the rear as once again the experienced and capable MacDonald had to rapidly re-deploy amidst the chaos of battle and impose discipline on frightened men with parched throats, sweaty palms and ever on the verge of panic. It must have seemed as if he was being assailed from all directions but now reinforced by an Egyptian Brigade on his left and the Lincolnshire Regiment coming up on his right the Dervish were mown down like skittles.

Yet, had Ali-Wad-Helu co-ordinated his attack with that of the Black Flag MacDonald’s Brigade may well have been overwhelmed and the outcome of the Battle very different. Indeed, Winston Churchill was to express less admiration for the performance of the Sudanese Brigade than others claiming that they had been in a funk and firing wildly and indiscriminately and had only been saved from annihilation by the timely arrival and well-disciplined enfilading fire of the Lincolnshire Regiment; and a careful audit of ammunition expended did reveal that in the final assault each Sudanese and Egyptian trooper had fired on average sixty rounds, an extraordinary amount for a single-shot weapon. But such criticism seems churlish, 0jand it was not widely shared.

In a final tragic denouement to events 400 Baggara horsemen appeared and charged Macdonald’s line, all were shot down.

As the dust began to settle it became increasingly clear that the Dervish Army had been destroyed in both manpower and spirit. They had lost more than 12,000 men killed, 13,000 wounded, with a further 5,000 taken prisoner.

Despite all the fury of the battle the Anglo-Egyptian Expeditionary Force lost just 47 men killed and 382 wounded, fewer casualties than they had suffered in the engagement at Atbara five months earlier.

It had been a great slaughter and one who had witnessed it later described the scene:

“They could never get near, yet they refused to hold back. It was not a battle but an execution. The bodies were not in heaps – bodies hardly ever are – but spread over acres and acres. Some lay very composedly with their slippers placed under their heads for a pillow, some knelt cut short in the middle of a last prayer. Others were torn to pieces.”

No weapon had been more effective at Omdurman than the Maxim gun for which a terrain of flat earth and open spaces could not have been more ideal as they swept the landscape reaping a rich and deadly harvest. In his book on the campaign in the Sudan, The River War, Winston Churchill described the impact of the Maxim gun:

“A dozen Dervishes are standing on a sandy knoll. All in a moment the dust jumps in front of them, and then the clump of horsemen melts into a jumble on the ground, and a couple of scared survivors scurry for cover.”

The Battle of Omdurman spawned the author Hilaire Belloc’s famous line:

“Whatever happens we have got the Maxim gun and they have not.”

It was a sentiment echoed perhaps more profoundly by the philosopher Bertrand Russell who saw that courage and belief in one’s cause was no longer enough:

“Ironclads and Maxim guns must (in future) be the arbiters of metaphysical truth.”

With the Dervish threat eliminated Kitchener ordered his troops to advance with fixed bayonets to clear the field and force any remaining Dervish west into the desert. They were also ordered to despatch any wounded encountered unable to shift for themselves, and to do so with the bayonet so as to save on ammunition.

The Khalifa had in the meantime fled to Omdurman where he ordered what remained of his army to join him and defend the city. The order was largely ignored and unable to fight on he later abandoned the city riding a donkey through an opened gate during the hours of darkness, a handful of die-hard loyalists following in his wake. Shortly after the Khalifa’s hasty departure the Sirdar occupied Omdurman with barely a shot being fired in its defence, Khartoum soon followed.

When news of the victory at Omdurman reached Britain, it was greeted with joy and no little satisfaction as the newspaper headlines screamed – Gordon Avenged! And General Kitchener became the great hero of the late-Victorian era. His reputation soared even further when not long after he thwarted a French incursion into the Upper–Nile in a bloodless confrontation that became known as the Fashoda Incident.

The public also revelled in the four Victoria Crosses that were awarded at Omdurman all to men who had fought with the 21st Lancers, the greatest cavalry charge since the Light Brigade at Balaclava, and as it transpired the last such in British military history. They were the heroes of the battle much to the chagrin of Kitchener who sought to heap praise on MacDonald’s Brigade and their gallant defence of the rear-guard.

While Kitchener received the thanks and plaudits of a grateful nation the Khalifa, who was hiding out in the desert proved incapable of rallying his forces sufficiently or revive his Ansar Movement that had been so savagely mauled. He was killed on 24 November 1899, when his much-diminished army was routed at the Battle of Umm Diwaikarat.

The more brutal aspects of the Sudan campaign such as the killing of prisoners and the desecration of the Mahdi’s Tomb were overlooked, at least by the public who were little interested in the subsequent Inquiry into inappropriate conduct which failed to gain any traction and ended without much fuss in Kitchener’s complete exoneration.

On 31 October 1898, General Kitchener became Baron Kitchener of Khartoum, Lord K of K, and was to be a surprisingly enlightened Governor of the Sudan given the brutality of its conquest. He was later to bring the Boer War to a successful conclusion and in August 1914 was appointed Minister of War lending his image to one of the world’s most iconic posters.

Share this post: