Battle of Tsu Shima

Posted on 12th September 2021

The Meiji Restoration of 1868, the elimination of the Shogun, and the subsequent suppression of the Samurai had seen Japan undergo a period of unprecedented modernisation, and social change but the spirit of the Samurai lived on however, in their martial spirit and in their political ambitions.

A resurgent and confident Japan now saw itself as the natural successor to its traditional enemy, a now weak and ineffective China as the dominant power in South-East Asia but their strategy for doing so was impeded by the continuing presence of the Russian Empire and tensions between the two countries had been simmering for many years.

Russia had already extended its territories into Manchuria and Korea areas that Japan considered to be within its own sphere of influence and vital to its security. Negotiations between the two countries to find a settlement of their differences had been underway for sometime but the Russians who had already reneged on a series of agreements were no longer considered by the Japanese to be trustworthy. Indeed, their attitude in the negotiations had been one of contempt for a people they so evidently considered to be inferior.

So the Russians continued to encroach on still disputed territory and had expanded the trans-Siberian Railway as far as the port of Vladivostok though it was only operational during the summer months.

In 1897 they exploited the weakness of China following its defeat in the Sino-Japanese War of 1894-5 to acquire Port Arthur with its all season, deep-water harbour despite the fact that it had earlier been ceded to the Japanese following the subsequent Treaty of Shimonoseki but under pressure from the Western Powers they had been forced to yield it up. Now that the Russians had the lease on it the Japanese feared they would go onto occupy the whole of the Liaotung Peninsula.

Once the construction of the trans-Siberian Railway was complete the Japanese knew that the Russians would be able to speedily reinforce and re-supply their armies in the Far-East and with their Pacific Fleet already stationed at Port Arthur they knew they would have to act, and act fast, if they were to thwart Russian imperial ambitions. If they could destroy the Russian Fleet anchored at Port Arthur as a fait accompli then they could return to the negotiating table in a position of strength. Late on the night of 8 February 1904, they attacked.

As the home base of the Pacific Fleet Port Arthur was heavily fortified but it was not in a state of preparedness and as the Japanese warships closed in there were few patrol boats in operation and most of the Russian fleets officers were ashore attending a party, and it was only the fact that the anti-infiltration nets were in place that prevented a catastrophe. So despite achieving total surprise and severely damaging several Russian ships the attack had failed in its aim to neutralise the Russian fleet as an effective fighting force.

The suddenness of the attack had stunned the Tsar and the Russian High Command in St Petersburg, however. Indeed, so much so that they did not issue their own declaration of war for another eight days.

The indecision in St Petersburg and the Russian forces at Port Arthur doing little in the way of retaliation allowed the Japanese to land forces on the Korean peninsula unopposed.

It wasn’t until the arrival of Admiral Stepan Makarov at Port Arthur on 24 February that things began to change.

Admiral Makarov was considered a man of action and he was determined to do everything in his power to bring the Japanese Fleet to battle. He maintained a state of heightened readiness at all times, kept the fleet in battle formation even when they were moored in harbour, ensured that the harbour entrance was patrolled by ships of the Cruiser Squadron, and made regular forays with the fleet into the Yellow Sea in an attempt to seek out the enemy. He also ordered that should enemy ships appear on the horizon they were to be immediately pursued and engaged.

On the 13 April, the Russian Strasny was returning to port when she was intercepted and attacked by a number of Japanese destroyers. Upon seeing this Makarov ordered the cruiser Bayan to go to the Strasny’s assistance whilst he set off in pursuit of the Japanese Fleet.

As they had done many times before however, the Japanese withdrew until they came under the protection of the guns of their main battle-fleet. Aware that he was out-gunned and beyond the support of his shore batteries Makarov decided to return to port but as his flagship, the Petropavlovsk neared the entrance to the harbour she struck a mine and sank in just minutes taking 679 men, including the Admiral, with her.

The Japanese later recovered his body from the wreckage and returned it to the Russians in Port Arthur with full military honours but his death was a blow from which the Russian Pacific Fleet and the defenders at Port Arthur never fully recovered.

The Russian’s slow response to the Japanese attack saw Japanese forces quickly sweep across the Korean Peninsula and into Russian occupied Manchuria. The first major land engagement took place at the Yalu River on 1 May 1904 and the Japanese showed themselves willing to accept high casualties in capturing entrenched Russian positions and the often heavily outnumbered Russians were forced to retreat as defeat quickly followed upon defeat.

By July, they had been forced back as far as Port Arthur itself which soon found itself under siege from both land and sea.

The Russians were also hampered by problems of reinforcement and re-supply, the trans-Siberian Railway was not yet complete and the Russian General’s without urgent assistance had proved, themselves incapable of stemming the Japanese tide. If a swift and humiliating defeat were to be avoided then drastic action had to be taken.

Fearing that Port Arthur might fall in August the Russian Pacific Fleet was ordered to break out and make its way to Vladivostok to link up with the Cruiser Squadron based there. The Japanese Navy were hot on their heels and following a series of inconclusive engagements in the Yellow Sea that saw the Russian Fleet become dispersed, so much so that the battleship Tsarevich ended up seeking shelter in the Chinese port of Tsingtao, the attempt to reach Vladivostok was abandoned.

The Fleet was ordered to return to Port Arthur where its Commander General Anatoly Stoessel now began to strip some of the ships of their guns to reinforce his shore batteries; with defeat looming and under pressure from his senior Commanders, Tsar Nicholas II reluctantly agreed to dispatch the Russian Baltic Fleet to assist them.

The plan was to relieve Port Arthur, link up with the First Pacific Fleet and then overwhelm the Japanese Navy in one decisive engagement. The Japanese advance into Manchuria would then be impeded sufficiently for Russian reinforcements to arrive in such numbers that they could turn the tide of the war.

It was a bold but also a desperate plan, for though the Baltic Fleet included four recently built battleships some had barely had their sea-trials and many of the crew were poorly paid conscripts who’d had only partial, if any training. Indeed, some had never even been to sea before.

The Fleet would also have to sail the equivalent of 25,000 miles, re-fuelling and re-supply was to prove a serious problem, and morale was low with many of the sailors believing the war already lost and that they were being sent on a suicide mission.

Nevertheless, every available ship was mustered – 8 battleships, 8 cruisers, 9 destroyers, and even 3 old coastal defence vessels, along with numerous support ships.

The Fleet set sail from various Baltic ports on 15 October, 1904.

IIt was to be commanded by the 54 year old Admiral Zinovy Petrovich Rozhestvensky, an iron-disciplinarian and man of quick fiery temperament who was not afraid to display his displeasure to his subordinates. Indeed, such was his demeanour he was known as “Mad Dog” though never to his face.

He was a veteran Commander who had experienced naval warfare before but it would take all his skill to command a Fleet on an epic voyage with crews so inexperienced that gunnery practice would have to take place en-route.

The emergence of the powerful Russian Baltic Fleet in the North Sea sent shivers down the backs of most of the Western Powers who if truth were known relished the thought of a Japanese victory. As such, their ports were closed to the Russians who would have to re-supply and re-fuel their coal powered vessels at sea.

Logistical problems were not Rozhestvensky’s only concern, however. He feared to the point of paranoia an attack by fast moving Japanese Torpedo Boats.

The torpedo was a fairly recent and frightful innovation and Rozhestvensky, who already believed that he was being followed and closely monitored was convinced that they would come at night when they could not be seen and so the sea around his fleet was constantly lit up by the sweep of searchlights and the sound of warning klaxons and false alarms rent the still night air. His paranoia was to have almost fatal consequences for the entire mission.

In the early hours of 22 October, small vessels spotted in the distance were mistaken for Japanese Torpedo Boats and a number of Russian ships opened fire. They had in fact just encountered British trawlers fishing off the Dogger Bank, one of which, the Crane, was sunk and three men killed while several others were damaged and crewmen injured. Upon receiving news of the incident the Royal Navy was mobilised to intercept the Russian Fleet.

Frantic messages were exchanged between the two Governments and an international incident and possible conflict was only avoided because of the Russian’s swift apology, agreement to abide by the rulings of an independent tribunal, and their willingness to pay compensation.

Things did not improve any for Rozhestvensky when the British denied him permission to sail his fleet through the Suez Canal and they would now have to take the laborious and hazardous route around Africa and Cape Horn.

More worrying still perhaps was the fact that during the encounter at the Dogger Bank Russian ships had fired upon each other, and one had released more 500 shells and not hit anything.

The rest of the voyage was to remain fairly incident free but it was long, arduous, and morale sapping with insubordination becoming an almost daily occurrence.

Earlier on the 15 May, the Russians in Port Arthur had avenged the loss of the Petropavlovsk and the death of Admiral Makarov when two Japanese battleships, the Yashima and Hatsuse struck mines and sunk with great loss of life in full view of those on shore. The loss of the two battleships proved a serious set-back for the Japanese Commander Heihachiro Togo and reinforced his much criticised policy of caution first.

Admiral Togo Heihachiro had been raised in the Samurai tradition and as a young man had a reputation as a hot-head who was not afraid to use his fists in an argument but had since learned to rein in his temper and caution had long since become his watchword but he did not shirk decisive action where it was required.

He had received his naval training in England where he impressed those who knew him with his hard work and depth of knowledge. A veteran of the Sino-Japanese War he had been appointed Commander-in-Chief of the Japanese Imperial Fleet in 1903, much to the surprise of everyone and ahead of a number of his seniors.

On 2 January 1905, after just under a year of siege General Anatoly Stoessel surrendered Port Arthur.

The capitulation came as a complete surprise for the Japanese had made numerous attempts to storm the fortifications and had been beaten back with heavy losses. It was evident that they could neither break in nor the Russians break out and that there was stalemate.

The Japanese took 24,000 prisoners and were astonished to find Port Arthur amply stocked with food, ammunition and other supplies. Why Stoessel surrendered Port Arthur when he did remains a mystery and upon his return to Russia from captivity he was court-martialled and sentenced to death for cowardice and dereliction of duty. His sentence was later commuted to a dishonourable discharge.

The loss of Port Arthur and the surrender of the Pacific Fleet was a devastating blow. The plan for the Baltic Fleet to link up with the Pacific Fleet and together overwhelm the Japanese was now at an end and new orders were issued for the Baltic Fleet to make its way to Vladivostok.

By the 27 May 1905, after seven months at sea the Baltic Fleet was at last nearing its destination.

As he approached the Yellow Sea, Rozhestvensky had three available routes to Vladivostok but with supplies low, indiscipline rife, and desperate to make landfall he chose the most direct one through the Straits of Tsu-Shima. He hoped to do so speedily and unobserved – but Admiral Togo had second-guessed him.

Upon receiving news of the Baltic Fleet’s approach Togo ordered his ships to take up position in the Straits and manoeuvre so as to cross the T of the advancing Russian fleet and be sideways on so they could bring all of their guns to bear.

On a dark moonless night and with a thick fog descending, Rozhestvensky remained confident that he could pass through undetected but at 02.45 the Japanese Armed Merchantman Shinano Maru spotted the Russian Hospital Ship Oryol that had kept its lights on in accordance with the rules of war. Worse for Rozhestvensky the Captain of the Oryol had mistaken the Shinano Maru for a Russian ship and did not the report the incident.

The sighting of the Oryol had given the Japanese a long time to prepare and unaware that he had been sighted Rozhestvensky ploughed on at full speed to exactly where the Japanese Fleet was waiting for him.

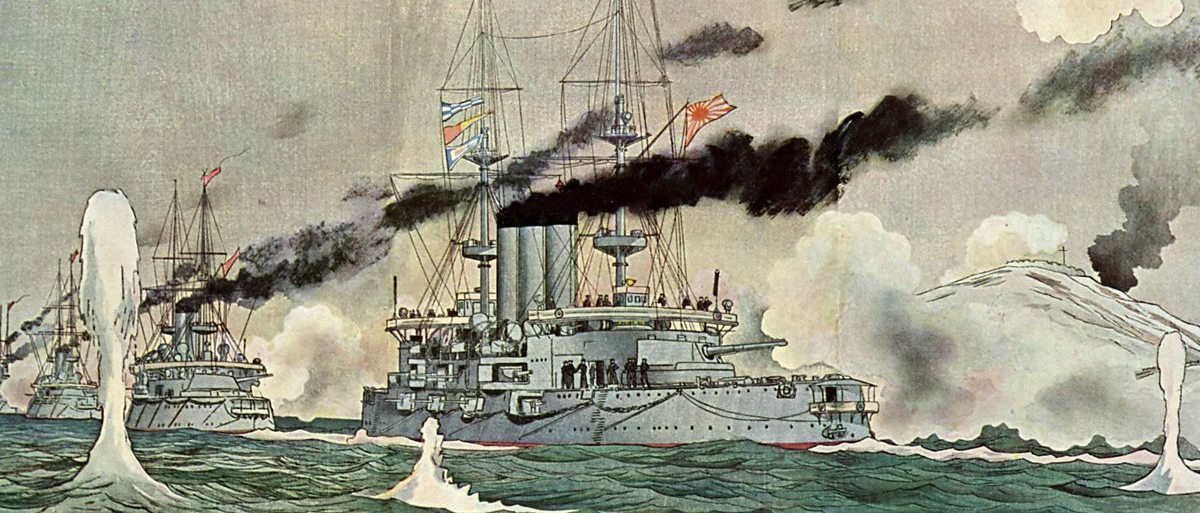

At 14.08 the following day, sailing in single file with Rozhestvensky’s flagship Knyaz Suvorov in the lead they encountered the Japanese Fleet.

Rozhestvensky immediately ordered his forward batteries to open fire at a distance of 7,000 yards. Despite being at a tactical disadvantage with his ships only being able to bring their forward turrets to bear he was determined to take the fight to the Japanese and force a way through.

Just fifteen minutes into the attack the battleship Oslyabya was badly hit and fell out of formation. Almost immediately she was descended upon by 6 Japanese destroyers who loosed their torpedoes at close range. Trying to manoeuvre and with the force of her guns rocking her to and thro she rapidly took on water and became unstable. In an attempt to compensate for the imbalance and as a precaution against possible ignition Captain, Vladimir Ber ordered the starboard magazine to be flooded, but he had miscalculated, and the Oslyabya capsized. She sank soon after, taking Captain Ber and 473 of her crew with her.

The Knyaz Suvorov now came under heavy shellfire and took such damage that she was temporarily forced to leave the line. She later returned but it was not long before a shell hit the bridge rendering Rozhestvensky unconscious and injuring most of the other senior Officers on the bridge. By this time the Suvorov was ablaze and had slowed to just 4 knots making her a sitting target and so at 17.30 the destroyer Buinyi came alongside to evacuate Rozhestvensky and the other wounded Officers.

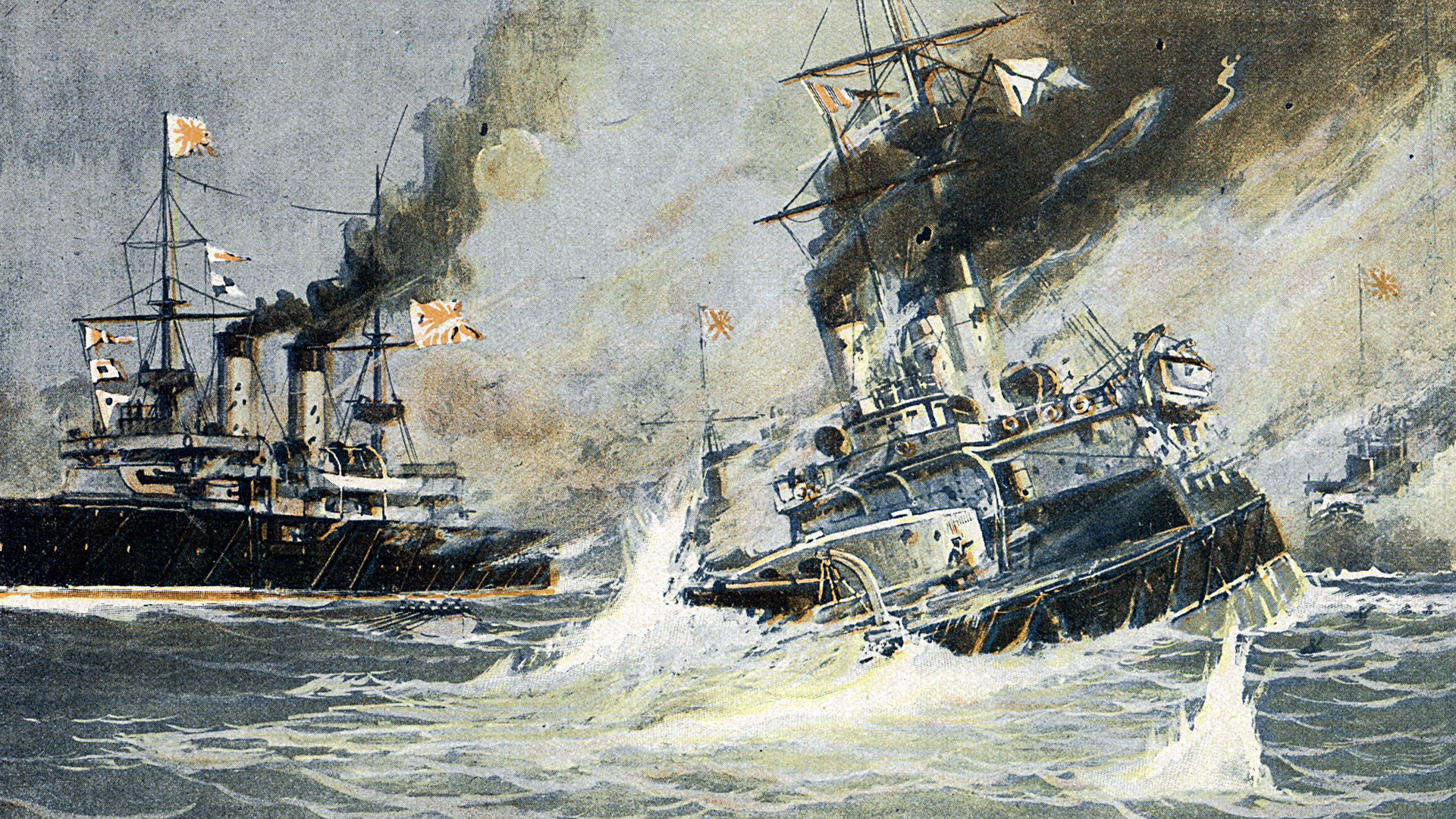

A little later the Captain of the battleship Imperator Aleksandr III, Nikolay Bukhustov, charged at full speed towards the Japanese formation in an attempt to deflect fire from the crippled Knyaz Suvorov. For a time he succeeded but at a high price. At 18.30 under heavy fire with her deck ablaze and the men trapped inside the hull unable to get out she capsized and went down with all hands.

Around the same time as the Imperator Aleksandr III capsized a shell hit the Knyaz Suvorov’s forward magazine sparking a massive explosion that saw her sink taking many souls with her.

A little earlier the battleship Borodino had been devastated by a massive detonation that had sent her to the bottom in just minutes with only one of her crew of 855 surviving.

The daylight engagement had been a disaster for the Russians who had lost four battleships and numerous smaller vessels with heavy loss of life whilst barely damaging the Japanese Fleet at all. Her untrained crews of mostly raw recruits had proved themselves wholly inadequate to the task of fighting a major naval engagement. The guns were slow to fire and inaccurate, re-supply to the main batteries was inefficient and could not be sustained, and they proved incapable of fighting fires and flooding in the lower decks which merely sowed panic rather than any organised attempt to keep the ships afloat.

Nightfall brought a brief respite for the Russians and for a few nervous hours Admiral Togo feared that the remainder of the Russian Fleet had escaped in the darkness.

The Russians however, still fearful of attack by Japanese torpedo boats had turned on their searchlights to scan the sea around them thereby giving away their position and they now reaped what they had most feared as Togo withdrew his capital ships and dispatched 21 destroyers and 37 torpedo boats to hunt them down.

Since the incapacitation of Admiral Rozhestvensky command of the Russian Fleet had fallen to Admiral Nikolai Nebogatov but there was little he could do as most of his ships had already dispersed.

During the night another battleship, the Navarino, was sunk when it struck a mine with only 3 of its crew of 622 being rescued.

With the prospect of any further organised resistance at an end the Captain of the Sisoy Veliki chose to scuttle his ship rather than face the humiliation of it falling into Japanese hands. Similarly, the Armoured Cruisers Admiral Nakhimoff and Vladimir Monomakh chose the same fate.

Despite his best endeavours Admiral Nebogatov had failed to keep his decimated fleet together and by 10.30 the following morning he found himself surrounded by Togo’s ships near the Island of Takeshima and with only six ships under his direct command he knew the situation was hopeless but he was also aware that for a Captain to surrender his ship at sea was deemed an act of cowardice the penalty for which was death. Further resistance however would cost many more lives than just his own and it was a sacrifice he was not willing to make. He addressed his men: “You are young, and it is you who will one day retrieve and restore the honour and glory of the Russian Navy. The lives of the two thousand four hundred men in these ships are more important to me than my own.” At 10.57 am he raised the White Flag and the Battle of Tsu-Shima was over.

Of the 38 ships of the Russian Baltic Fleet that had set sail 223 days earlier only 3 ever made it to Vladivostok.

All 8 battleships had been sunk along with 13 smaller vessels, 2 had been scuttled, 6 had been captured, and 6 had escaped to neutral ports where they were interned. More than 4,500 Russian sailors had been killed and almost 6,000 captured. The Japanese had lost just 3 motor torpedo boats and 117 men killed – it was one of the most decisive victories in all naval history.

Admiral Togo was to return to Japan where he was showered with honours and lauded as the Nelson of the East, he had led the Battle Fleet of a nation that had only 40 years earlier decided to modernise to victory over one of the great Imperial powers of the world. It was a remarkable achievement and his status as a national hero was assured.

The same could not be said for Admiral Rozhestvensky, who along with Admiral Nebogatov, were returned from captivity to face a court-martial where found guilty and sentenced to death they were quietly pardoned by the Tsar and permitted to endure their humiliation in obscurity.

Following the destruction of their Fleet in the Straits of Tsu-Shima any real prospect of a Russian victory in the land campaign disappeared.

The revolution that broke out in Russia January 1905, had since escalated and meant troops could no longer be spared for the front, and also aware that disenchantment with the war was one of the primary factors for the trouble at home the Tsar sought an end to hostilities.

In 25 November 1905, following negotiations presided over by the President of the United States Theodore Roosevelt, for which he later won the Nobel Peace Prize, they signed the Treaty of Portsmouth ceding Korea to the Japanese and withdrawing their forces from Manchuria. But they refused to pay an indemnity or accept any responsibility for the war.

Just five years later the Japanese invaded and occupied Korea as they would likewise do to Manchuria. Russian Imperial ambitions in the East had been eclipsed by the new power in the region.

Although the Japanese victory over the supposedly mighty Russian Empire shocked many the emergence of a formidable new power on the world stage still wasn’t fully grasped.

It was an error that would return to haunt those incapable of learning the lessons of even the recent past.

Share this post: