Battle of Waterloo: A Near Run Thing

Posted on 17th April 2021

Following the disastrous failure of his ill-conceived campaign in Russia the Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte who had ridden rough-shod over the Continent of Europe for more than a decade was forced onto the defensive for the first time.

The success of the Russians had encouraged his enemies to form yet another Coalition against him and whilst the armies of Great Britain and Spain advanced from the south those of Austria, Russia, Prussia and Sweden advanced from the north and east in a great encircling pincer movement.

Advised to retreat to the interior of France the ever-belligerent Napoleon instead decided to confront his enemies but at the Battle of the Nations fought just outside Leipzig between 16 and 19 October 1813, his army went down to an overwhelming defeat.

Despite many minor victories in the coming months, he was unable to stem the Allies inexorable advance yet with his once Grand Armee reduced to little more than 90,000 men and the Coalition Forces now numbering close a million he still wanted to fight on. His Generals however seeing that defeat was inevitable refused to support him and on 11 April 1814 with Paris already lost and alone in the Palace of Fontainbleu contemplating suicide, he abdicated.

He had feared for his life but was in fact treated surprisingly well by those powers upon whose sovereignty he had trampled and against who he had waged war with such ruthless efficiency for so many years.

Exiled to the Mediterranean island of Elba he was provided with a generous allowance, permitted to take with him a small standing army and even allowed to retain the title of Emperor - but this was never going to be enough for a Man of Destiny.

It appeared to those watching that he was busy ruling his tiny Kingdom but all the time he was plotting his return. On 26 February 1815 he escaped and three days later on 1 March, with just 600 men landed near Antibes in the South of France. News of his arrival soon spread, and panic ensued in Paris.

The recently reconstituted Bourbon Monarchy in the form of Louis XVIII (the brother of the previously executed Louis XVI) ordered Marshal Ney, once one of Napoleon's finest Generals described by the Emperor himself as the Bravest of the Brave, to take the Fifth Regiment and intercept him before he reached Paris.

Ney accepted the commission and promised to return with the Emperor in an iron cage.

In the meantime, Napoleon had been shocked to discover the people were not flocking to his cause as he had expected. They remembered all too well that more than 2 million Frenchmen had died in his many wars and there was little enthusiasm for having him back.

On 7 March, his advance on Paris was halted near the city of Grenoble by Ney who lined up his troops in overwhelming force barring his way. Napoleon knew that any confrontation could only end badly for him, yet surrender was not an option. The moment had come, he dismounted from his horse and walking towards the soldiers that had been sent to arrest him he unbuttoned his coat, bore his chest and shouted: "Here I am, kill your Emperor if you wish.” Silence descended upon the scene and for a time there was a tense stand-off as both sides eyed one another nervously. Finally, the silence was broken by a shout of Vive le Empereur! It was followed by more shouts as the chant soon went from a ripple to a wave flowing through the French ranks. The old soldiers had simply been unable to fire upon the man who brought them such glory. Napoleon had put his life on the line and won the day. Witnessing this Marshal Ney changed sides and pledged his allegiance once more to his Emperor who now had an army with which to march on Paris.

Learning of Ney's defection and not needing to be reminded of brother’s fate Louis XVIII could not get out of Paris quick enough. Bonaparte was once again Emperor of France, a feat he had achieved largely through force of personality not of arms.

The Coalition Allies who were still squabbling at the Congress of Vienna that was to decide the post-Napoleonic settlement of Europe were thrown into by confusion and panic by the sudden turn of events. Could the devil really be back? It was the realisation of their worst nightmare. They declared him an outlaw and hastily agreed to form another Coalition with each of them vowing to put an army of at least 150,000 men in the field.

Back in Paris, Napoleon hastily wrote and despatched letters to the leaders of all the major powers of Europe declaring that he had turned over a new leaf and that all he sought was peace and the opportunity to rebuild France - no one believed a word of it. As far as the Allies were concerned he remained the personification of the Revolution he had in truth done so much to corrupt and destroy. They believed he wanted to export its values and to make Europe French, and all believed his lust for power was insatiable. The letters he sent were not responded to and the one he sent to the Prince Regent in England was returned unopened.

With his peace overtures rejected he prepared for war but he knew that to emerge victorious he had to strike quickly and defeat each Allied army piecemeal before they could gather their strength.

As the Coalition hastily reorganised its forces the only army available to face the new threat was that of Sir Arthur Wellesley, the Duke of Wellington. He had made his reputation as the victor of the Peninsula War and was the only man who had defeated Napoleon’s forces consistently on the field of battle though he had never faced him in person.

Wellington was Britain’s greatest General, the Iron Duke, noted for his calm under pressure which was to prove an asset indeed as he had already been informed by Tsar Alexander of Russia that the entire fate of Europe now lay in his hands.

Both men were known to loathe one another with Napoleon contemptuous of Wellington's abilities as a General while he despised Napoleon for not being a Gentleman. Both men who had been born in the same year were supremely confident in their own abilities and the Battle of Waterloo was to be a clash of egos as well as a campaign of tactical and strategic genius.

On the evening of 15 June 1815, the Duke of Wellington was attending the Duchess of Richmond's Grand Ball in Brussels. Always one of the social events of the year it was attended by various European nobility, local dignitaries and all the leading Officers of Wellington's Army.

The Duke was enjoying being the centre of attention when he was handed a note by the Prince of Orange and people could see from the change in the Duke's countenance that it was a serious matter and a hush descended upon the ballroom. With his demeanour one of calm self-assurance he made his excuses and departed to a side room where poring over some maps he was heard to remark: "Napoleon has humbugged me, by God. He has stolen twenty-four hours on me.” While the Iron Duke had been quaffing champagne and charming the ladies, the Emperor had made his move.

Napoleon's Army numbered 117,000 men of whom some 74,000 were to fight at Waterloo. Most were veterans of his previous campaigns as he had not had the time to conscript many new troops to swell the ranks. But he at least knew that his troops were experienced and reliable.

Wellington's Army by contrast was a rag-tag affair of different nationalities and variable quality. He had 26,000 British troops, 20,000 Dutch and Belgian (many of whom had previously fought for Napoleon) 17,000 soldiers from the German States of Nassau and Hanover and the 6,000 troops of the King's German Legion. Wellington was not only outnumbered but he considered his Dutch and Belgian Regiments so unreliable that he placed British troops within their ranks to stiffen their resolve. There was however, a 50,000 strong Prussian Army stationed just 6 miles away at Ligny.

On 16 June, Napoleon set out to destroy this army and with the Prussians taken completely by surprise he very nearly did so. In a day of bloody and bitter fighting they were severely beaten and forced to withdraw but they weren't routed and did so in good order.

This was largely down to their 72-year-old Commander Field-Marshal Gebhard von Blucher, a grizzled old veteran of numerous campaigns against the French. An austere man who survived on a diet of onions, coffee and gin when in the field he hated Napoleon with a vengeance it being said that he would tear him apart with his bare hands if he had the opportunity.

Known as Marshal Vorwarts or Forwards by his men because this was the only order, he ever seemed to give he was by no means a great General but his sheer bloody-mindedness and refusal to accept defeat made him a dangerous and formidable opponent.

Blucher had been everywhere on the battlefield rallying his men until wounded he remained trapped beneath his horse for several hours. Many thought he had been killed and in his absence, it was his Second-in-Command General August von Gneisenau who withdrew the Prussian Army intact, if badly mauled. Blucher was later rescued by his Aide-de-Camp. After a brief rest and liberal quantities of brandy Blucher resumed command of his army and despite being advised to withdraw north he instead took his army on a forced march to the town of Wavre, close enough to lend Wellington support if needed, as he had promised he would.

At around the same time as the beleaguered Prussians were desperately trying to remain a coherent fighting unit, Napoleon dispatched Marshal Ney with orders to capture the crossroads at Quatre Bras on the road between Charleroi and Brussels, a vital junction for any future attack upon the Belgian capital.

The Duke of Wellington later admitted that he had been taken completely by surprise by the direction of Napoleon's attack and Quatre Bras was only lightly defended by Dutch troops under the command of the Prince of Orange. With Wellington's forces still gathering and the Prussian's effectively out of the action its fall at this time would have left the road to Brussels wide open and would have spelt disaster for the Coalition forces. But inexplicably, Ney now delayed his assault and for hours nothing happened. By the time he ordered an all-out assault on the crossroads Wellington had arrived on the field with almost his entire army.

The fighting was fierce and was to cost the French 10,000 casualties when earlier they could have swept the opposition aside with hardly a shot being fired.

The Prussian withdrawal at Ligny was to eventually force the abandonment of Quatre Bras but its defence had bought Wellington valuable time and he now withdrew his army further north to occupy the ridge of Mont St Jean just south of the village of Waterloo.

He had chosen his ground well having reconnoitred it the previous year and familiar with the terrain he hid most of his troops in the folds of the ground where they would find some protection from Napoleon's vastly superior artillery.

Napoleon mistakenly believed that he had decisively defeated the Prussians and that military common sense dictated they would now withdraw back towards the Rhine to protect their lines of communication and await reinforcements. But he also knew Blucher so he sent the untried and inexperienced Marshal Grouchy with 33,000 troops to harass the Prussians and prevent them from providing any support to Wellington should they try.

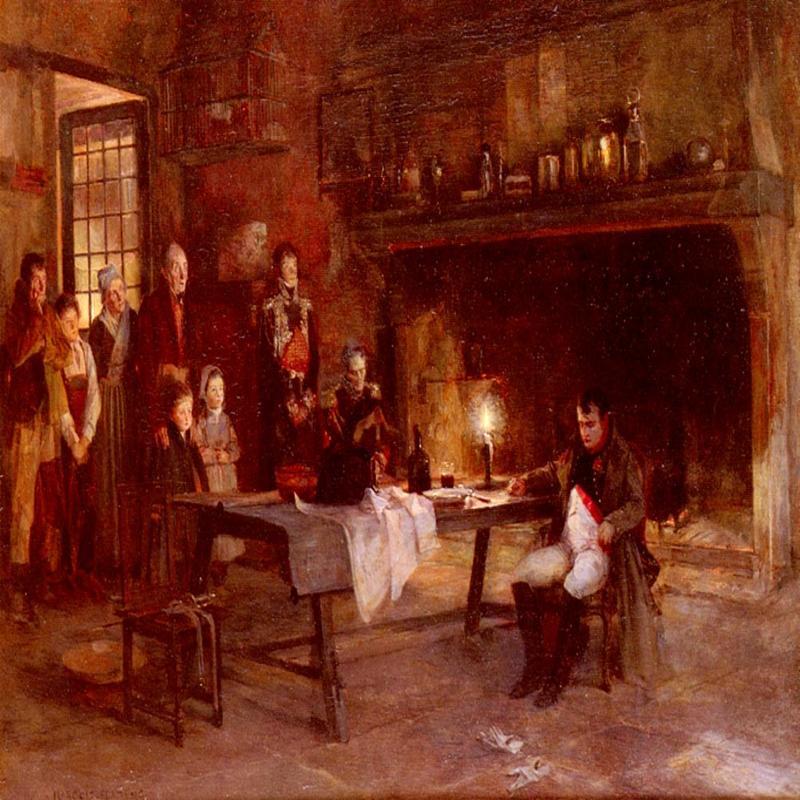

Despite the initial disappointment at Quatre Bras, Napoleon could be well pleased with his day’s work. The crossroads had finally fallen, the Prussians had been defeated and an army placed between them and Wellington. The Iron Duke had been outmanoeuvred and forced onto the defensive so it was with a sense of satisfaction and quiet self-confidence that he took breakfast on the morning of 18 June.

His Generals did not share his confidence however, they had fought Wellington before, were aware of his abilities and they urged caution. Marshal Soult even went as far as to insist that Grouchy be recalled but Napoleon remained dismissive: "Just because you have been beaten by Wellington you think he is a good General. I tell you he is a bad General, the English bad soldiers, and this affair is no more difficult than eating our breakfast." At that moment a British artillery shell tore through the room where they were dining decapitating Napoleon's chef.

Napoleon would start the battle as he always did with an intense artillery barrage, as an artillery Officer he knew the value of well-directed cannon fire but torrential rain throughout the previous night had left the ground sodden and, in some places, little better than a quagmire. This limited the effectiveness of his artillery so he delayed his assault to allow time for the ground to dry out, but it was time he did not have.

Wellington made the most of the delay by fortifying two large farmhouses Hougemont and La Haye Sainte that lay between the armies. They were to be used as positions from which to break up any advance by the French Infantry. Hougemont was also meant to protect Wellingtons left flank and keep the route to the coast open and possible evacuation should the worst happen.

Napoleon was aware of Wellington's concern about maintaining his link to the French coast which was the obvious route of any British withdrawal. So, at 11.30 on 18 June 1815, the much-delayed Battle of Waterloo began with a diversionary attack upon the strong-point of Hougemont. Napoleon believed that Wellington would pour in his reserves to hold onto it at all costs but rather than reinforce it Wellington simply issued the order to the garrison already present that it must be held to the last man if necessary and o fierce was the resistance to be that it became a matter of honour for the French to take it.

Hougemont was defended by Units of the Coldstream Guards under James MacDonnell, though he was later supported by Du Plat's Brigade of the King's German Legion.

They soon came under attack from Colonel Bauduin's 1st Brigade who easily cleared the fields and woods surrounding the farmhouse, but the clearing in-between soon became a killing ground as the initial assault was repulsed with great loss of life. Bauduin remained undeterred and the attacks continued until eventually a Lieutenant Legros, wielding a huge axe managed to break down the north gate. Hougemont was now in danger of falling as French troops began to pour in through the breach. MacDonnell, seeing the danger led a small number of his own Officers in a desperate counterattack that managed to close the breach and more than 30 French soldiers including the aforesaid Legros found, themselves trapped within the confines of the farmhouse. They were all were killed in vicious hand-to-hand fighting.

Napoleon had waited to almost midday before ordering the artillery bombardment to begin but the ground had not dried out sufficiently to make it effective. Also, Wellington's clever use of the folds in the ground had shielded his men from the danger of the cannon balls many of which had sunk harmlessly into the mud in any case.

At 13.00, an unusually hesitant Bonaparte ordered the main assault to begin. He sent D'Erlon's 1st Corps, some 16,000 men, to attack Wellington's line just to the left of the fortified farmhouse of Le Haye Sainte. Facing the brunt of the attack were 6,000 British, Dutch and Belgian troops under the command of Colonel Sir Thomas Picton.

Le Haye Sainte was soon enveloped in the attack and Napoleon ordered it taken and the soldiers of the King's German Legion defending it came under such a furious assault they were barely able to hang on while the Hanoverian Luneberg Brigade that was sent to break the envelopment were caught in a deadly crossfire and decimated.

The Pressure of D'Erlon's attack soon began to tell with one Dutch Battalion abandoning the field altogether. Sir Thomas Picton had also been killed trying desperately to rally his men. Now leaderless and in a state of some confusion the British line began to buckle, and a French breakthrough appeared imminent.

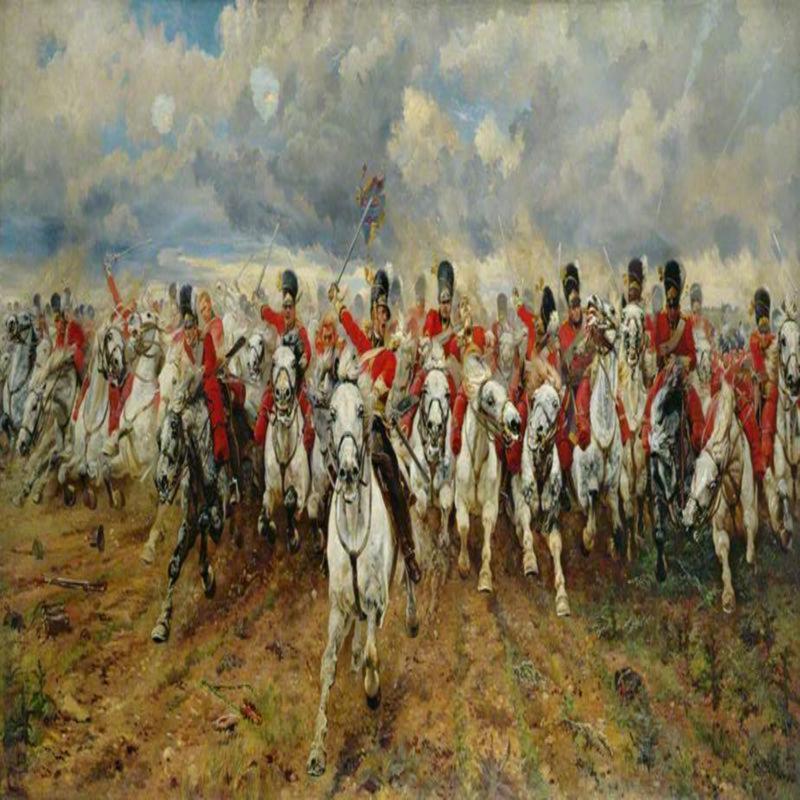

The Duke of Wellington, who had previously described his cavalry as "amateurs who lacked both tactical and common sense”, had somewhat surprisingly given them carte-blanche to intervene on the battlefield when and where they saw fit. Lord Uxbridge, the Officer in Command, seeing the British line begin to buckle saw fit to intervene now.

He ordered the First Brigade under Lord Somerset and the Second Brigade "Scots Greys" under Lord Ponsonby to attack D'Erlon's advancing Infantry head on. The enthusiasm of the British Cavalry for the charge was evident as with the cheers from the British lines ringing in their ears, they smashed in the French troops shattering their attack.

Their intervention which had quite literally been in the nick of time now became impossible to halt and on and on they went until they reached the French guns. Both men and horses were by now exhausted when Napoleon now ordered his Lancers to counterattack. Bogged down in the wet and soggy ground the British were neither able to extricate themselves in time or had the energy to make their escape and overrun by their pursuers they were cut to pieces. Of the 2,261 men who had made the charge 664 were killed and many more wounded. Few made it back to the British lines and the Scot's Grey's had almost been wiped out. Lord Ponsonby was speared to death by a French Lancer just as his father had been many years earlier.

The British cavalry had ceased to be a significant factor in the battle, but for now at least they had saved the day.

At around 13.50, just as the main French assault was being forced back the first reports that the Prussians had been sighted approaching the battlefield were filtering back to Napoleon's Headquarters at La Belle Alliance. Time was not now on the Emperor's side.

One of the most famous exchanges of the day had taken place when Wellington and his Second-in Command Lord Uxbridge perusing the battlefield heard the fearful sound of a cannon ball pass nearby. Moments later Lord Uxbridge calmly remarked, "By God, I appear to have lost my leg, Sir.” Wellington glanced down briefly and without looking Uxbridge in the eye replied, "By God, so you have, Sir."

At very great risk to himself Wellington toured the battlefield cajoling his Officers, encouraging his men and constantly altering his dispositions. This was in sharp contrast to Napoleon who appeared strangely lethargic. He was hesitant and indecisive, and his old genius seemed to have deserted him.

With General Reille's Sixth Division still tied up at Hougemont which was only ever meant to have been a diversionary attack and D'Erlon's Corps shattered Napoleon was running out of men and options. He had earlier sent orders for Grouchy to abandon his pursuit of the Prussians and return to the battlefield, but nothing had been seen or heard of him.

At 15.00 he ordered Marshal Ney to take Le Haye Sainte in a hurry as a stop-off point for any future advance by the Imperial Guard. He then went for a lie down.

Marshal Ney was determined to make amends for his hesitancy at Quatre Bras two days earlier and at around 4 pm an hour after his assault on Le Haye Sainte had begun he saw what he believed were British troops withdrawing from the field of battle. What he had in fact seen was British wounded being taken to the rear. Mistaking this for a retreat he ordered his cavalry to attack and press home their advantage.

Seeing the massed formation of 9,000 Cuirassiers their breastplates glinting in the sunlight advancing towards them the British hastily formed themselves into defensive squares.

It was against all military precedent to launch a cavalry attack on a prepared position without infantry and artillery support, but it made for a glorious sight as wave after wave of French cavalry charged the British Squares yelling loudly, cutting and swiping with their sabres and firing their carbines. Unable to break the British formations they weaved in and out and between the Squares constantly changing the direction of their attack - thousands were killed.

When Napoleon arrived on the scene awake now from his slumbers, he could not believe what he saw but could do little to change it - the assault continued.

Ney had wasted more precious time and even more lives and when he demanded Infantry to support his attack the Emperor acidly replied: "More troops, and where do you expect me to get them from, do you expect me to make them.” Eventually cannon were brought forward to disperse the British Squares and in the resulting cannonade the 6th Inniskillings were virtually wiped out.

As the fighting raged across the battlefield Napoleon could be heard constantly exclaiming "Where's Grouchy!" Where was Grouchy and where were the Prussians?

Grouchy, who had been ordered to keep the Prussians from the battlefield had indeed engaged them at Wavre but had been unable to prevent Blucher from releasing troops to support Wellington. Now Napoleon desperately needed his 33,000 troops and they were nowhere to be seen, and those Prussians were now beginning to arrive on the battlefield in significant numbers.

At 18.00 the King’s German Legion having run out of ammunition were forced to withdraw from Le Haye Sainte which at last fell to the French. Its abandonment exposed Wellington’s centre to attack and provided a last opportunity for Napoleon to snatch victory.

The farmhouse would now provide cover for his last throw of the dice - the advance of the Imperial Old Guard. These veteran soldiers, many of whom had served him for almost twenty years and had volunteered to form hiss army on Elba were his shock troops and had never been defeated in battle; but then he had always been loath to commit them unless necessary and had declined to do so at Borodino three years earlier - but this was different.

The situation in Wellington's army appeared even more desperate, they were short of ammunition and the reluctance on the part of the Belgian and Dutch troops to engage had meant that the burden of the fighting had fallen on select British and German Units.

Wellington, who had been an ever-present on the battlefield, had cleverly dispersed his troops and had not fallen for any of Napoleon's ruses but his men were by now exhausted and severely reduced in numbers. The British line was beginning to falter and under the constant pressure was in danger of crumbling altogether. It drove Wellington to exclaim: "God, give me Blucher, or give me night”.

Just after 19.30 the Old Guard, some 20,000 strong, emerged from the area around Le Haye Sainte to begin their advance. They had been told that the firing they could hear in the distance were Grouchy's men returning to the battlefield. It was in fact Blucher's Prussians.

The Old Guard split into three columns and despite being peppered by British artillery and rifle fire closed ranks where gaps appeared in the line and maintained their discipline.

The advance continued and was making headway, the first British line had been breached and overrun and things were looking ominous - the pivotal moment of the battle had been reached when suddenly 1,500 British Foot Guards under Sir Peregrine Maitland that had been lying low in the corn to protect them from the French Artillery rose and devastated the Imperial Guard with a series of volleys at point-blank range. The Guard halted, wavered, and began to fall back.

Once again Wellington was on the scene and riding up shouted, "Now Maitland, now is your time!" Maitland ordered his men to charge with fixed bayonets and the Guard began to flee the field. As they did so Wellington rose in the saddle of his horse Copenhagen and waving his hat in the air ordered a general advance. The entire French Army just looked on in amazement as the Imperial Guard, never before defeated in battle were running away. The cry went up "The Guard retreats save yourselves!"

In the meantime, the Prussians had captured the village of Plancenoit on the French right and were now arriving on the battlefield in force. Witnessing the arrival of the Prussians the French Army began to disintegrate and in no time at all it was in full flight.

Those surviving Units of the Imperial Guard now rallied and formed Squares to help facilitate what Napoleon still hoped would be an orderly withdrawal, but it was a forlorn hope and the French were later described as running like rabbits. Many of the Imperial Guard refused to surrender however, despite repeated calls to do so and were mown down by artillery fire.

The pursuit that had been relentless and savage particularly by the Prussian Cavalry who were eager to avenge their years of humiliation at the hands of the French wasn’t called off until 23.00 hours.

Wellington had earlier met Blucher at La Belle Alliance, Napoleon's old headquarters. As neither spoke the others language they merely saluted and shook hands as co-victors.

In a day of bloody fighting Wellington had lost 13,000 men killed and an equal number of wounded, more than 7,000 Prussians had also been killed. The French had lost 20,000 killed and wounded with a further 8,000 taken prisoner. As Wellington surveyed the carnage of the battlefield he remarked: "My heart is broken by the terrible loss I have sustained, believe me, nothing except a battle lost can be half so melancholy as a battle won”.

In a single afternoon on an otherwise anonymous belt of agricultural land in rural Belgium the course of European and world history had been changed forever.

Napoleon, who had chosen not to remain and fight it out with his men, was still determined to continue the struggle but it soon became apparent that this was not possible and on 24 June 1815, he abdicated for the second time. What has since become known to history as the Hundred Days was over.

Fearing to return to Paris he had earlier gone into hiding but there really was nowhere for the world's most wanted man to hide. Finally, on 15 July fearing for his life should he fall into the hands of the Prussians he travelled to the port of Rochefort and surrendered himself to the Captain of HMS Belleraphon. He handed him a letter addressed to the Prince Regent it read: "I claim from your Royal Highness the protection of the laws of England, and throw myself upon the mercy of the most powerful, constant, and generous of my enemies."

Napoleon's life was spared, the Coalition not wanting to make a martyr of him but here the generosity ended. He was exiled once more but this time to the Island of St Helena, a rocky outcrop in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean just 47 square kilometres in circumference and 2,000 miles from the nearest significant land mass. There he died on 5 May 1821 aged 53, supposedly of cancer though many have long believed that he was poisoned with arsenic.

Gebhard von Blucher retired to his estates in Silesia where he was held in great esteem as the Old Warrior and showered with honours. But his last campaign had stripped him of his vigour and severely damaged his health. Hedied just four years later in 1819, aged 76.

The Duke of Wellington returned to Britain a true national hero and his public appearances were many. Always the honoured guest at dinner parties’ crowds would spontaneously cheer, applaud and chant his nickname "Iron Duke" whenever his carriage passed. But he was honest enough to admit that the Battle of Waterloo had been: “The damn-nearest run thing you ever saw in your life.”

Retiring from the Army he entered politics where as a leading member of the Tory Party he became Prime Minister in 1828 and though deeply conservative ever the pragmatist he forced through the Catholic Emancipation Act thus ending hundreds of years of religious exclusion and division. But he was never as popular as a politician as he had been as a soldier and the windows of his home at Apsley House were smashed on several occasions. Yet the esteem in which he was held as the man who had defeated Bonaparte never wavered.

He was to command an army for the last time in 1848 when he took charge of the troops that had been mobilised to prevent the Chartist demonstrators who had gathered at Kennington Park from marching on the Houses of Parliament. In the end the demonstrators agreed to return home and the Iron Duke was never faced with the dilemma of having to turn the guns on his own countrymen. He died on 15 September 1852, aged 83, while drinking a cup of tea. The city of London came to a halt to attend his State Funeral.

Postscript:

In a national poll conducted by the BBC the Duke of Wellington was voted the 15th greatest ever Briton. He should perhaps have been higher for few people have had the opportunity to change the course of world history in a single afternoon, and even fewer have taken it.

Share this post: