Beau Brummell

Posted on 15th March 2023

He was a fashion icon, the first of his kind, a man known for little more than the clothes he wore and the manner of his being – fragrant, polished, charming, and stylish but with a rapier wit and a sharp tongue. He was Beau Brummell, man about town and dandy. Famous in his own lifetime he would become even more so after his death, though it would take time.

He was born George Bryan Brummell on 7 July 1778, in Downing Street, London, where his father was employed as Private Secretary to the Prime Minister Lord North. His family then, were wealthy and respected but they were not of noble blood. Even so, William Brummell was determined that his son’s would be raised as if they were - they would be gentlemen.

In the case of his younger son George, he needn’t have worried for if he had anything at all it was a high self-regard and the air of superiority that comes from being raised within the corridors of power. He also had an overwhelming desire not to go unnoticed and both the poise and self-confidence to ensure that he didn’t. Aware that few can know you, but all can see you image was important and his time at Eton Public School, which he attended as a fee-paying student, was a great success. There were few who met him even as a child who forgot the experience but his was not merely the triumph of style over substance, he was also an intelligent young man who early on had perceived a clear path to success.

After Eton he briefly attended Oxford University where he likely met George, Prince of Wales for the first time. The future Prince Regent and King George IV was impressed by this young man with such style, wit, and self-regard, enamoured even - the young George Brummell had hooked a big fish.

When his father died in June 1794, leaving him £20,000 in his Will he abandoned his studies at Oxford in favour of purchasing a commission in the Royal Hussars, the Prince’s Own Regiment, so he could remain close to the man who would provide his meal ticket to fame and fortune; but to do so wasn’t cheap and he could only afford the rank of Cornet not nearly exalted enough to gain him access to the Prince but at a time when such things were not earned but lay in the gift of family and friends Brummell was promoted first to Lieutenant and then to Captain. His access to the prince was assured but when the Regiment was transferred to Manchester, he resigned his commission so he could remain in London declaring that he could not bear to dwell among the destitute and unwashed in a place of, “undistinguished ambience with such a want of civility and culture.”

He also begged the Executors of his father’s Will (he had still not yet come of age) to buy for him a house in Mayfair which they did but at great cost- Brummell cared little, it was money well spent.

Prince George who cared more for his image than he did his crown and craved the admiration of his peers more than he did the love of his people was both vain and easily flattered. His critics might paint him as a lazy, gluttonous dolt rightly lampooned in the press and jeered at on the streets, but he saw himself very differently. He was the most handsome man in Europe, the best dressed man, and the epitome of good taste. He knew this because the by now ‘Beau’ Brummell told him so.

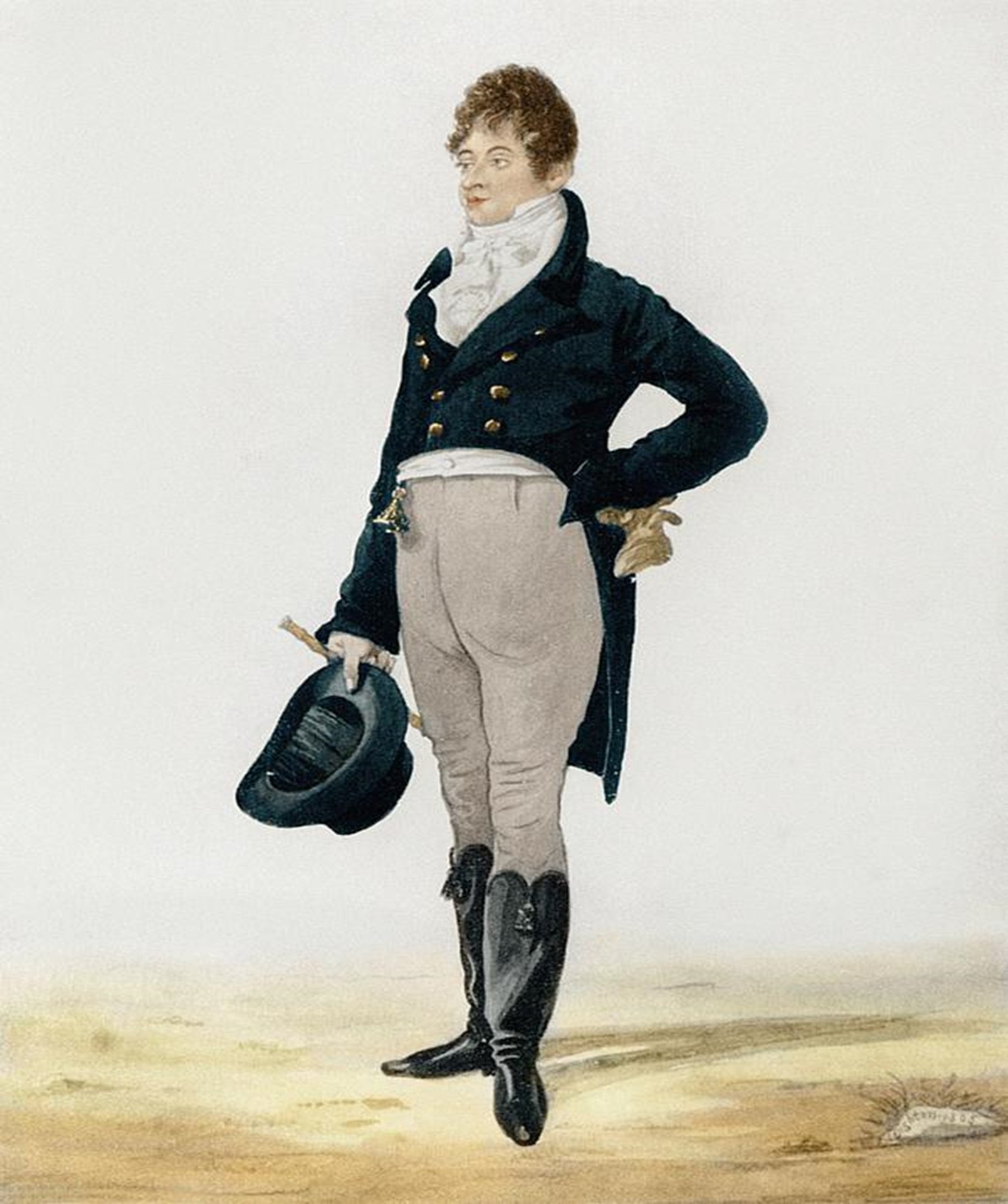

By the early 1800’s Brummell’s Mayfair home at 4 Chesterfield Street had become the point of contact for the wealthy and the fashionable. His immaculate but understated style of dress at a time when the gaudy and the garish was de rigueur caused quite a stir. One did not need to be vulgar to be noticed it seemed, and Brummell’s dark blue jackets, silk and linen shirts, spotless white breeches, elaborately knotted neck cloths and knee-high leather boots it was said he had polished in champagne became a familiar sight at Rotten Row and in the salons and ballrooms of Old London Town.

Never less than immaculately dressed his personal regimen was no less exacting and he bathed daily at a time when such was rare, gargled and brushed his teeth regularly in champagne and perfumed his hair. It was rumoured it took him five hours to dress and that the prince would often be present when he did so.

But being a Dandy and the most fashionable man in England was an expensive business made more so perhaps by his association with the prince, as also was the need to be seen and Brummell was a regular attendee of the racecourse and at the gaming tables while no elegant salon or grand ball was complete without his presence. Once when asked how much it cost to keep a gentleman in clothes he responded, “Why with tolerable economy, I think it might be done with £800 more or less.” This was at a time when the average wage for a skilled craftsman was only around £50 a year.

Brummell was perhaps being flippant but then he was almost as famous for the sharpness of his wit as he was the elegance of his apparel. When a woman shouted down to him from a balcony, he was passing beneath whether he would take tea with her he replied: “Madam, you take medicine, you take a walk, you take a liberty, but you drink tea.”

Lady Hester Stanhope recalled in her memoirs how on another occasion he told her:

“My Dear Lady Hester, it is my folly that is the making of me. If I did not impertinently stare Duchesses out of countenance, and nod over my shoulder to a Prince, I should be forgotten in a week.”

In this latter remark at least, he was being prescient.

He also flirted outrageously with just about any attractive woman of substance who crossed his path. His most significant relationship was with Frederica, Duchess of York, and he kept a painted miniature of her left eye on his person indicating a high degree of intimacy and he once presented her with a pet dog he named Fidelity as a gift but for the most part his courtships were short and inconsequential. He was known to frequent the bedchambers of prostitutes the most famous of whom was Miss Julia Storer, a high-class courtesan who did not sell herself cheaply.

With a fortune long spent and no discernible income to speak of Brummell nonetheless absented himself from few events on the social calendar aware that if one cannot be seen one may as well be naked. Heavily in debt and with an expensive lifestyle to maintain Brummell’s credit remained good as long as his friendship with the prince continued but their relationship came under strain when in 1811 due to his father’s mental incapacity he was elevated to Prince Regent or King in all but name.

Both Brummell and the Prince mixed in fashionable Whig circles, the former because he believed in the free trade policies they advocated and the Republican sentiments they often expressed, the latter as a deliberate snub to his father. Now that George was Prince Regent his allegiance switched to the pro-Monarchy Tory Party, an unforgiveable betrayal as far as Brummell was concerned and he told him so.

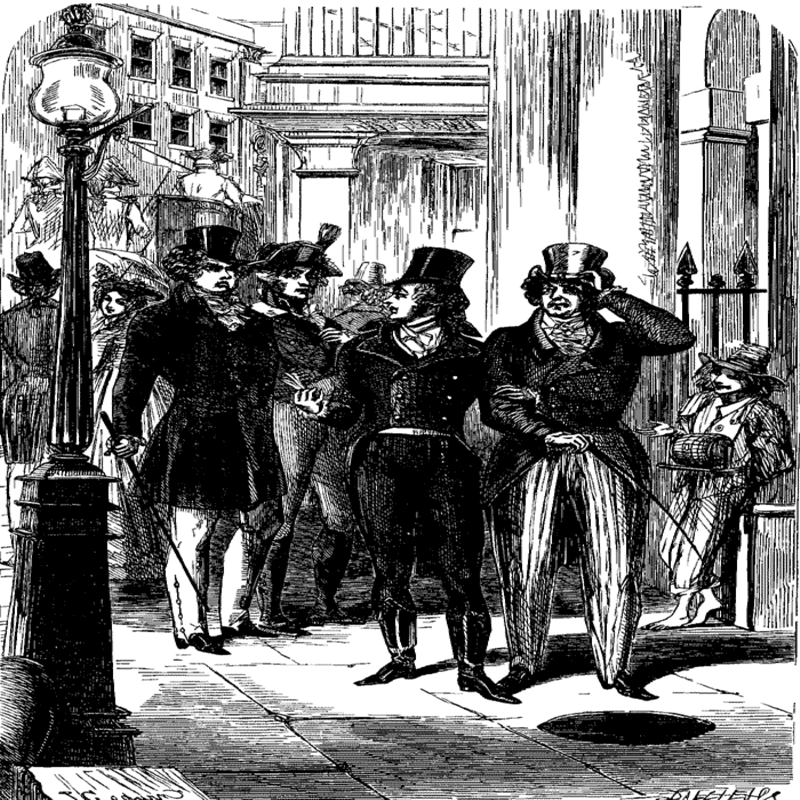

The prince who was used to the flattery and sycophancy of the Royal Court did not take kindly to home truths and so it proved with Beau Brummell and no longer would he seek his advice on where to be seen and how to dress. Their worsening relationship came to a head in July 1813, at the Masquerade Ball at Watiers Private Club (also known as the Dandy Club) in Mayfair organised by Brummell’s close friends Lord Alvanley and Sir Henry Mildmay. The Prince Regent was honoured guest but upon his arrival and after warmly greeting both Alvanley and Mildmay he deliberately ignored Brummell but in a manner that made it plain to all those present that he had done so. The affronted Brummell sensitive to the snub turned and said in a loud voice, “So Alvanley, who is your fat friend?” The room fell silent and the prince left soon after -the two men would never speak again.

At first it seemed that Brummell might be able to weather the storm of royal disfavour but without the prince’s patronage the credit dried up and his friends began to abandon him. No longer welcome in the homes of the great and the good and pursued by his creditors one of whom, Richard Meyler, demanded satisfaction in the form of a duel, in May 1816 he departed from Dover for the Continent.

Once in France those influential friends who had remained loyal secured for him a post at the British Consulate in Calais. It was rumoured that the Prince Regent had intervened on his behalf but as they never publicly reconciled this seems unlikely though it appears clear he did not stand in the way of his appointment.

It would be wrong to suggest that the once infamous Beau Brummell settled easily into a life of relative obscurity. He missed the limelight and was resentful towards those who had deprived him of it and had abandoned him in such haste. It was a resentment that would only increase as the years passed and he was already showing signs of the syphilis that would take a toll on both his body and his mind. With his behaviour becoming increasingly erratic visits from friends became less frequent. Indeed, so insufferable did he become he even managed to talk himself out of his job at the Consulate by arguing that the post was superfluous and should be abolished.

Despite his increasingly dire circumstances he refused repeated requests to return to England afraid more of the mockery and ridicule he might receive than he was his creditors. Neither would he write his memoirs as a means of relieving his financial difficulties.

By 1835, he was in Debtors Prison and reliant once more upon friends to liberate him, which they did paying for his release, renting for him a house and even providing him with a modest income of sorts; but by this time his health was in sharp decline, and he was a shadow of the man he once was. Shabbily dressed and unkempt there was the merest glimmer of the old Beau Brummell in his air of grandeur and the cast of his eye but shuffling and bowed with his speech rambling and incoherent it was a glimmer only.

Confined to an Insane Asylum in Caen he refused any further help and so there he remained his fast-diminishing grip on reality subsumed in the bitter imaginings of better times and the mis-characterisation of other inmates as the Lords and Ladies he once knew.

Beau Brummell, once the most talked about man in England died on 30 March 1840, aged 61, his passing barely remarked upon in the society pages of a press he once dominated.

Tagged as: Georgian

Share this post: