Bodyline: Bradman, Jardine, and the Ashes

Posted on 9th March 2021

Don Bradman is without question one of the greatest competitors ever to grace the sporting arena with few able to boast a career record that bears comparison. By the age of just 22 he already held the record for the highest Test Score, the highest First-Class score, and the most runs scored in a single day. Yet the best was still to come.

He was a run machine, a batting colossus who no one seemed able to stop. But one man would find a way and the tactics he would adopt in doing so would result in the most controversial Ashes Series of all time.

Donald George Bradman was born on 27 August 1908 in Cootamundra, Australia but his parents soon after moved to the town of Bowral where from an early age he became obsessed with cricket and the story of him practising his technique by hitting a golf ball against a wall using a cricket stump as a bat has become a part of Australian folklore.

At the age of 12 he scored a century in his first game for his school team and a little later played for his hometown side who having found themselves a man down gave him the opportunity to play despite his youth and lack of stature He went onto score 37 and 29 runs not out. In 1921, his father took him to watch the Fifth and final Ashes Test Match at the Sydney Cricket Ground and utterly transfixed the young Donald remarked: I shall never be satisfied until I play on this ground.

Leaving school aged 14, he worked for a local Estate Agent who recognising his talent allowed him time away from work to play cricket. The young Bradman on his part was determined to make cricket his life.

Continuing to play for his hometown team his consistently high scoring soon brought him to the attention of the New South Wales Cricket Board and in 1926 he was selected to play for St George in Sydney where he scored a century on his debut.

In the winter of 1928-29, England toured Australia in defence of the Ashes that the ageing home team had so limply ceded two years earlier. Bradman was eager to be selected for the Series and proceeded to make, himself almost impossible to overlook scoring a century in both Innings of the Sheffield Shield Match against Queensland, and then 132 not out against the touring England Team in a warmup match. The Australian press was clamouring for his inclusion and the Australian Selectors despite their reservations regarding his inexperience yielded to the pressure and so at the age of just 20 he was chosen to play in the First Test at Brisbane, the youngest player ever to do so. But it could not have gone worse.

Australia were bowled out in their First Innings for just 66 and were to go onto to lose the Test by a 675 runs a record margin of defeat that remains to this day with Bradman’s contribution a paltry 18 and 1. As a result he was dropped for the Second Test and feared that his fledgling international career was over before it had begun but Australia performed no better without him and with nowhere else to turn he was recalled to the side.

Australia was to lose the Third Test, but it remained a personal triumph for Bradman who scored 112 in the Second Innings making him the youngest player ever to score a Test century. He was to impress again in the Fifth Test scoring a further century and his statistics for the year saw him scoring at an average of 93.88.

The 1928-9 season was even more prolific for Bradman who averaged 113.28 including scores of 340 not out against Victoria and a new First-Class record of 452 not out against Queensland. The following year Australia was due to tour England but despite Bradman’s sensational record and the sporting press talking about little else the hosts remained largely unconcerned. He would soon be brought to earth by the inclement weather, the overcast conditions and the frequent breaks for rain that were common in England and the pitches so very different to the flat and fast ones he was used to in Australia. In any case, he must be a flash in the pan for otherwise he was simply too good to be true. They remained confident of retaining the Ashes and with something to spare. But it wasn’t to be, instead they became a stage for the young Bradman to promenade his skills to full stadiums of astonished spectators.

In the Five Test Series he hit scores of 131, 254, and during the Third Test at Lords he hit a century before lunch, another between lunch and tea, and finished with a score of 334 becoming the first man to hit 300 runs in a single day. In the Fifth Test Match at the Oval, he hit yet another double-century leaving English cricket stunned – they had never seen anything like it.

Against all the odds Australia had regained the Ashes and Bradman returned home a national hero. Bradman enjoyed his new fame and appreciated the work, the endorsements, and the money it brought him, but he was never comfortable with the adulation.

An intensely private and driven man who disliked any prying into his personal life he rarely formed close relationships, tended not to socialise with his teammates, was notorious for never buying a round of drinks and was thought unwilling to share his success with the rest of the team which was a little unfair as he had publicly declared that the Ashes victory had not been solely down to him. But this was perhaps not a humility he shared in the dressing room. He was considered aloof, even arrogant, and not an easy man to warm to. But as far as Australia was concerned, he could do no wrong.

The English who were due to contest the Ashes in Australia in 1932-33 were perplexed. What were they to do about Bradman? He had almost single-handedly destroyed them two years earlier when they had not only struggled to dismiss him but had failed even to slow him down. The London Chronicle wrote: As long as Australia, have Bradman she will remain invincible. It is almost time to request a legal limit be put on the number of runs he is permitted to score.

The English Captain for the forthcoming Ashes Series would be Douglas Jardine, a stiff-necked, humourless public-school martinet with an intense dislike of Australians. During the 1929 tour he had been barracked for slow play and verbally abused for refusing to engage in banter with the crowd. When he wore his public-school cap on the pitch, they thought he was being condescending and on one occasion when walking to the crease he was mocked with cries of “where’s the butler to carry your bat, mate?” He was not amused.

Being jeered to the crease, cheered when dismissed and not applauded for the decent shots he played riled him, and he was not shy in letting his dislike of those who did so be known. Australians he described as ignorant and uneducated barbarians. When it was put to him by a journalist that the Australian people had taken a dislike to him, he replied - Its fucking mutual.

In preparation for the Ashes Series to come Jardine watched film footage of the previous one – Bradman, in particular.

In the Final Test at the Oval, he noticed that Bradman who always stood perfectly still at the crease had clearly been discomfited by the short-pitched ball delivered at pace. This was not the first time that it had been noticed but as he had gone onto score 232 it was dismissed as a mere aberration and not as a means by which to dismiss him. Jardine clearly thought otherwise and rising suddenly from his chair declared out loud to his friends, “I’ve got it. He’s yellow.” He was vulnerable to the short-pitched fast delivery on the line of the leg stump because he was afraid of being hurt.

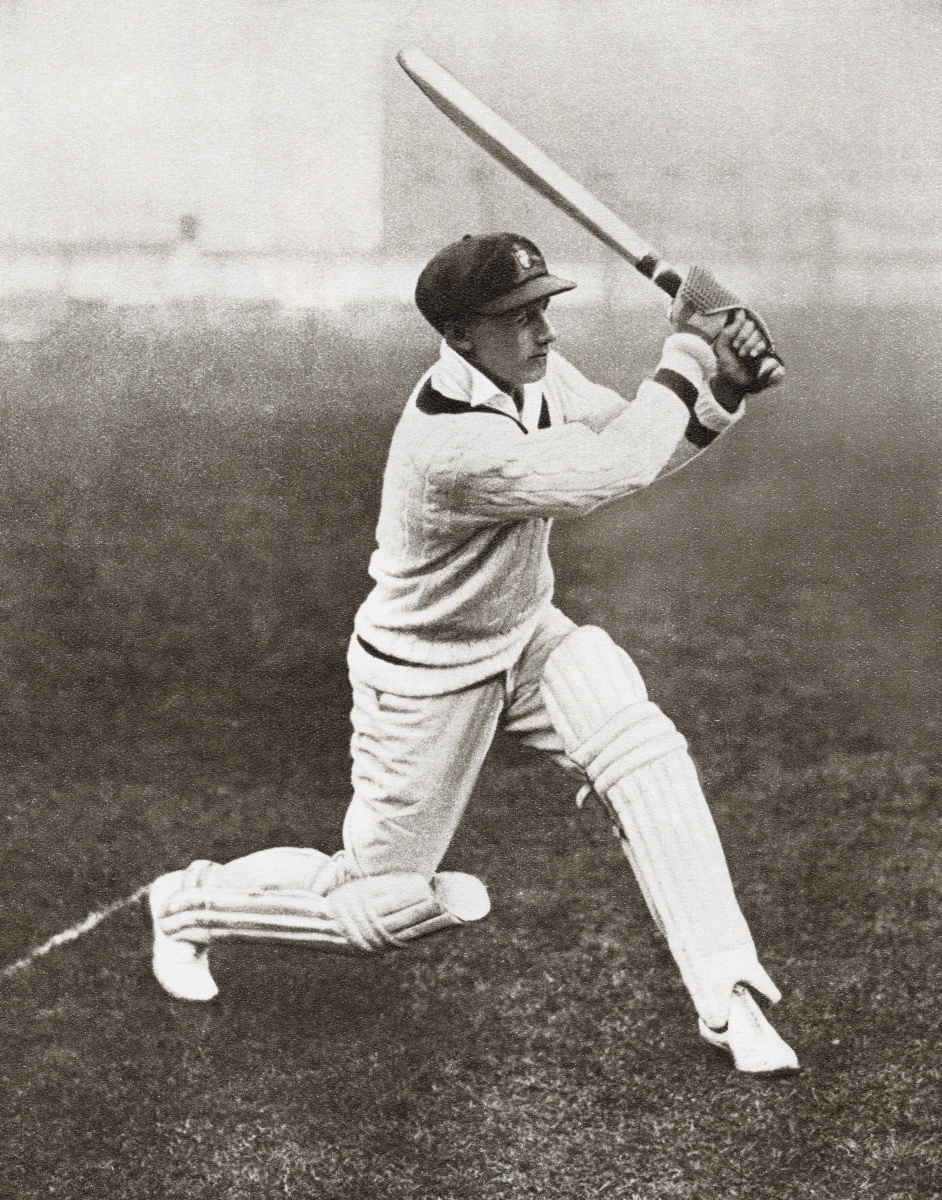

Following his formal appointment as Captain he arranged a meeting with England’s two leading fast bowlers Bill Voce and Harold Larwood at the Piccadilly Hotel in London. Both Voce and Larwood had been put to the sword by Bradman just two years earlier, but Jardine believed that they now held the key to reining him in and England regaining the Ashes. He particularly focused his attention upon Larwood, then the fastest bowler in the world.

Harold Larwood was the plain-speaking son of a Nottinghamshire miner who enjoyed nothing more than a beer and a woodbine during breaks in play and had briefly followed his father down the pit before playing county cricket. His electric pace and unerring accuracy would play a pivotal role in the events to come, and Jardine was to form a particularly close relationship with Larwood at a time when social distinctions were marked and Gentlemen and Players as they were known still had separate dressing rooms.

Over dinner Jardine quizzed the bowlers as to their opinion of Bradman and whether they felt confident that they could tender their deliveries short and at pace so that they would rise sharply into the batsman’s body? If this could be done, then the batsman would either - have to move away from the stumps to avoid being hit or play an uncontrolled shot and run the risk of being caught by the close leg-side field he would set. He would be demanding he told them and would insist upon maximum pace and unerring accuracy at all times.

By the end of the night an entire strategy had been designed to nullify the effectiveness of just one man and Fast Leg Theory as it became known had been born.

VVoce and Larwood proceeded to set leg-side fields in County matches and by the time the Ashes Series was due to begin they had perfected their bowling to it.

At team meetings prior to leaving for Australia, Jardine told his players that the only way to beat the Colonials, as he condescendingly referred to them, was to hate them as he did and that he wanted them to refer to Bradman in the future as that ‘Little Bastard’. They were going to win back the Ashes and if in doing so they made few friends then so be it. All he expected was that they obey his instructions on the pitch to the letter.

In October 1932, the English Touring Party sailed from Southampton on the three-week voyage to Australia.

The England Team Manager was Pelham ‘Plum’ Warner, an amiable and courteous man who had a good relationship with the Australian press and had been appointed in the belief that he could smooth over any problems that might be caused by the more abrasive and deeply unpopular England Captain. But even his well-honed diplomatic skills would be stretched to breaking point in the coming months.

In a warm-up match against an Invitational Australian XI in Melbourne, Jardine, who did not play himself, instructed his Vice-Captain Bob Wyatt to give leg-theory a run out. It was not well-received by the crowd as several the Australian players were struck by the short-pitched deliveries of Larwood and Voce.

In the weeks preceding the First Test Don Bradman became involved in a dispute with the Australian Cricket Board regarding his commercial and off-field activities. In particular, a contract he had signed to write for the Sydney Sun Newspaper. The rules made it clear that it was not permitted for an Australian player to write articles for a magazine or newspaper at the same time as representing his country.

Bradman was determined to fulfil the terms of his contract and avoid the financial penalties he would incur if he did not. But the Board would not back down, and they would not set a precedent by giving Bradman special dispensation to play.

The Australian public were outraged that their hero might be excluded from the team on the basis of some absurd technicality. But neither the Board nor Bradman would budge. The impasse was only broken when the owner of the Sydney Sun fearing a boycott of the newspaper should Bradman not play released him from his contract for the duration of the Ashes Series. But it had not been the best preparation and as it transpired Bradman withdrew from the First Test in any case, citing a mysterious illness.

Jardine was having none of it, he knew that Bradman had witnessed the use of leg-theory in Melbourne and believed he was running scared. He now questioned his courage even suggesting he might be having a nervous breakdown and his comments were quoted word-for-word in the press. Regardless of Jardine’s ill-intentioned barbs the First Test began at the Sydney Cricket Ground on 2 December 1932, without Bradman.

The Australians started well with the opening batsmen Ponsford and Woodfull scoring steadily if unspectacularly, but ripples of discontent could already be sensed coming from the crowd regarding the number of fast paced short-pitched deliveries.

This was a time when cricketers were afforded little protection against injury, there were no helmets, arm or chest guards and against the increasingly aggressive English bowling the wickets soon began to tumble with only Stan McCabe resisting for any amount of time hooking and cutting his way to an outstanding and courageous 187. But centuries by the batsmen Wally Hammond, Herbert Sutcliffe and the Nawab of Pataudi put England in a commanding position and they were to maintain their dominance to complete a comfortable ten wicket victory.

Even though leg theory had not been adopted in the First Test it did appear to some that the English bowlers had been aiming their deliveries not at the stumps but the batsman’s body. The concerns expressed did not bode well but the Second Test soon followed, and the return of Bradman saw 80,000 expectant spectators cram into the Melbourne Cricket Ground.

Australia had made a modest 2/67 when Bradman came to the crease. The crowd rose as one in acclamation as he strode from the Pavilion and began to chant his name as he tipped his cap in acknowledgement and took his mark. It was now that Jardine changed the field from an orthodox one to leg theory. Boos could be heard from around the stadium as Bill Voce ran in to bowl and expecting a short delivery Bradman shuffled across the crease missing the ball which went onto hit the stumps and remove the bails. He was out first ball without scoring.

There was a stunned silence as Bradman, bat tucked under his arm, made his way back to the Pavilion whilst Jardine did a war dance of jubilation on the pitch. As far as he was concerned his adoption of leg theory had been vindicated but his sense of satisfaction was to be short-lived as Bradman was to make 103 not out in his Second Innings and set Australia up for victory. Jardine was to complain that the pitch had been deliberately doctored to blunt the effectiveness of his bowling attack but there had also been dissent within the English dressing room.

During the match the Nawab of Pataudi had refused to take his place in the leg-side field and Jardine was heard to remark, “I see His Highness is a conscientious objector” The inference of cowardice was obvious, and the Nawab was dropped from the team and did not play again in the Series. He was later to say of his Captain, “I am told he has his good points. In three months, I have yet to see them.”

Several of the Australian batsmen had been hit by ’bouncers’ during the match including Jack Fingleton who had gone onto make a splendid 83 despite being hurt several times, but any sense of ire had been pacified in the warm afterglow of victory. Except for Bradman that is who complained bitterly that the tactics Jardine was adopting were unplayable, were making a mockery of cricket, and moreover would get someone killed.

For the rest of the Series, Bradman would adapt his batting style to cope with the short-pitched delivery moving away from the stumps and slashing the ball in somewhat ungainly style to the off-side where there were no fielders. It worked to a degree, but it provided little defence and left his wicket exposed, he would either score runs or he would be bowled.

By now the term ‘Bodyline’ was being used to describe the English bowling.

It had been coined when the journalist Hugh Buggy, who had intended to write that the English bowlers appeared to be following the line of the batsman’s body rather than bowling at the stumps. But at the time copy was sent by telegram and so to save money he had changed three words ‘line of body’ to one – bodyline. It was just a word, but a storm was brewing.

On 14 January 1933, a record Adelaide Oval crowd of 50,962 turned up to watch Australia’s reply to England’s First Innings total of 341. Rising to their feet as one to applaud and cheer every Australian batsman as they made their way to the crease, they in turn booed and jeered every English player as he came in to bowl.

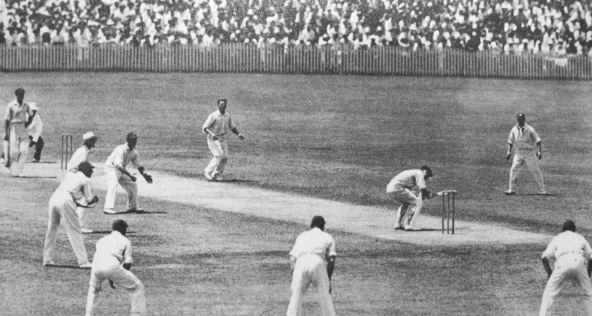

Perhaps in reaction to the crowd the English bowlers appeared particularly fired-up as they peppered the batsmen with short-pitched deliveries that arched sharply up to head height as they swayed from left to right to avoid being hit. The opening batsman Bill Ponsford had already taken to turning his body away from the ball exposing his back to injury when his partner Bill Woodfull, the Australian Captain, was struck with a heavy blow beneath the heart.

The crowd let out a collective gasp as the winded and clearly hurt Woodfull collapsed to his knees. As the other players gathered around him Jardine, who had kept his distance, could be heard to shout “Well bowled, Harold!” He then set a leg-side field. The crowd reacted with fury but this soon after turned to dismay as their hero Bradman was bowled out for just 8 runs.

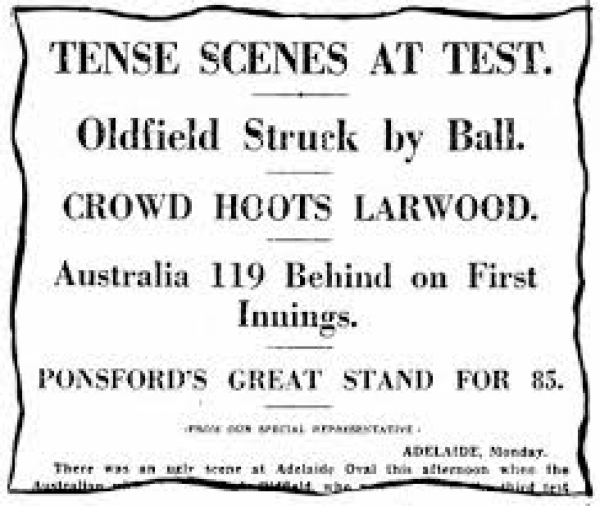

At 7/218 the veteran Australian wicket-keeper Bert Oldfield misread a ferocious ball from Harold Larwood that struck him a sickening blow on the temple that saw him drop his bat and stagger away from the wicket before collapsing to the ground unconscious.

As he was carried from the pitch with a broken skull the crowd erupted and fearing the worst police reinforcements were rushed to the ground and mounted policemen stationed on the boundaries edge. There was no pitch invasion, but the atmosphere remained toxic and tensions were running high.

Following the end of the days play Plum Warner visited the Australian dressing room to check on the welfare of Oldfield who was in hospital and express his regrets at what had occurred but before he could say a word, he was interrupted by Woodfull: “I do not wish to speak to you, Mr Warner. There are two teams out there, one is trying to play cricket the other is making no attempt to do so.” Warner tried to splutter an explanation, but Woodfull continued: “This sport is too good to be ruined. It is time some people got out of it.” A crestfallen Warner was ushered from the dressing room with tears in his eyes only to be bawled out later that evening by a furious Jardine who believed that he had visited the Australian dressing room to apologise.

Woodfull’s words which were intended to remain private were leaked to the press by someone. Jack Fingleton was accused at the time of being the culprit, but it appears now that it was almost certainly Bradman whose intense dislike of Jardine led him to try and undermine the England Captain whenever he could.

Fingleton certainly thought so and the fact that Bradman had been willing to allow him to take the blame was to be the cause of considerable acrimony between the two men for many years to come.

Over the next three days England were to wrap up a comfortable victory by 338 runs with only Bradman scoring a defiant 66 showing any resistance in the Australian Second Innings.

The result on the pitch became secondary to events off it however as the acrimony that had poisoned the tour from the outset took on a whole new dimension when under intense pressure both from the players and the press the Australian Cricket Board of Control sent the following telegram to the Marylebone Cricket Club, or M.C.C, under whose auspices the England Cricket Team played:

Bodyline bowling has assumed such proportions as to menace the best interests of the game, making the protection of the body by the batsman the main consideration. This is causing intensely bitter feeling between the players, as well as injury. In our opinion it is unsportsmanlike. If it is not stopped at once it is likely to upset friendly relations between Australia and England.

Despite Jardine’s repeated assertion that the M.C.C would buckle under pressure and abandon him they had in fact taken great offence at the accusation of unsportsmanlike behaviour and the inference contained within of cheating. They were unequivocal in their response demanding that the Australian Cricket Board withdraw their accusation of unsportsmanlike behaviour but adding that should it be thought in the best interests of the game they would cancel the remainder of the tour.

The Australian Cricket Board could not risk the loss of income that any cancellation would incur and so the exchange of telegrams that continued became gradually more conciliatory.

But the damage had already been done, tempers were frayed, and events were beginning to spiral out of control. A campaign was already underway to boycott British goods and dockworkers in Australian ports were refusing to unload British ships.

The British press already reporting the slur of unsportsmanlike behaviour in high dudgeon now condemned Australian attempts at intimidation while they in turn were outraged by what they saw as the British behaving as if they were still their Imperial masters. A diplomatic incident appeared imminent and it took the direct intervention of the Australian Prime Minister Joseph Lyons to calm things down.

Following a threat by Jardine to refuse to complete the tour unless the accusation of unsportsmanlike behaviour was withdrawn and an apology issued the Australian Cricket Board backed down and did so.

Bodyline, a term that Jardine detested and would not permit reference to in his presence knew full well that little else was being spoken about in the English dressing room and that it was causing dissent. The Nawab of Pataudi had already been dropped for refusing to participate and now Gubby Allen following a series of rows with Jardine both on and off the pitch declared that he would not participate if leg theory was implemented on the pitch. Relations between the two men went from bad to worse as Allen became increasingly isolated within the team. He later wrote home to his parents: “Jardine is more loathed than any German who fought in the Great War. Sometimes I feel as if I would like to kill him, and today is one of those days.”

Even the Vice-Captain Bob Wyatt had expressed concerns regarding bodyline, though he remained ambivalent as to its continued use. Larwood and Voce remained firmly behind their Captain however and backed him up to the hilt.

The split in the England camp increasingly appeared to be between amateurs and professionals between honour and victory at any cost. The atmosphere in the Australian dressing room by contrast had by now become one of grim determination. The bowler Bill O’Reilly was later to write: “We bade sentimental farewells to one another other as each batsman made his way out to the crease. We had a genuine feeling they were making a journey from which they might be borne back on a stretcher.”

Many of the Australian players were dismayed that their Cricket Board had so supinely withdrawn its accusation of unsportsmanlike behaviour and this manifested itself in a deep sense of betrayal but they nonetheless remained determined to battle on and defend the Ashes as best they could and on 10 February, the Fourth Test went ahead in Brisbane as planned.

Despite the furore with the Series not yet won Jardine refused to modify his tactics and the Australians were once more subjected to a barrage of short-pitched deliveries. Even so they made a decent First Innings total of 340 with Vic Richardson 83, and Don Bradman 76, top scoring. England struggled in their reply against some excellent bowling from Bill O’Reilly and Bert Ironmonger and closed the day on 6/216.

Being already a player short having lost the young Lancashire batsman Eddie Paynter to hospital with tonsillitis they were effectively 7/216. The following day much to everyone’s surprise Paynter came out to bat. Whether or not he had left his hospital bed from his own volition or had been persuaded to do so by Jardine who had visited him the previous night, remains uncertain.

As he took his mark at the crease the obviously weak and deathly pale Paynter was seen to be physically trembling but still, he managed to defend his wicket until the close of the days play. The next morning and looking no better he went onto score 83 as England finished the day on 356 all out.

Paynter’s courage and grim resolution, let alone his often extravagant shot-making, made him the only English player the Australian crowds really took to their hearts and he left the field to a standing ovation.

In the Second Innings the Australians collapsed to 175 all out and set the relatively small target of 160 which England chased down for the loss of just 4 wickets with Paynter scoring the winning runs with a huge six over cover point in what has been known ever since as the Eddie Paynter Test.

England had won back the Ashes and Jardine’s sense of achievement was immense - he had devised a way of negating Bradman and it had succeeded, he had set out to regain the Ashes and he had succeeded. But he received neither the congratulations nor the plaudits he could have expected.

The Australian press remained savage in their reporting of the tour, the English had set fields intended to prevent the Australians from playing, their bowlers had set out to deliberately injure the Australian players by following the line of the body, and that they had won the Ashes by cheating. If cricket matches were to be won by leaving batsmen semi-conscious on the ground and choking in the own blood then it wasn’t worth playing. Bodyline may have been within the laws of the game, but it wasn’t cricket, it wasn’t even within the spirit of common decency.

Back in London the Marylebone Cricket Club remained reticent and only the British press was unequivocal in its praise of Jardine and his achievements.

Jardine was incensed by the reaction of the Australian press but at the end of the day he had the Ashes and they did not and if anyone thought that with the Series won he would relent on Bodyline in the Fifth and Final Test at Sydney then they were sorely mistaken.

Despite the despondency that had gripped the nation the Australian team continued to battle it out and in the First Innings they set a challenging total of 435 but yet again they could not sustain it and another Second Innings collapse left England with a modest total to chase down which they did with something to spare to complete a 4-1 Ashes victory.

Don Bradman had top scored in the Series with an average 56.57 which by any standard would make him one of the great batsmen but his performances could not be judged by any normal standard and this was only half his career average to date. The Australian public were downhearted that perhaps the loathsome Jardine had been right after all, and that their hero did lack courage.

The man of the Series was undoubtedly the spearhead of the England attack Harold Larwood who took 33 wickets at an average of just 19.51.

Douglas Jardine returned to Britain with his team, a national hero. The press and the public had backed him throughout the controversy over Bodyline which they continued to refer to as legitimate leg theory.

He had been the man who had stopped the run machine Bradman and had regained the Ashes against all odds but there were murmurings within the cricketing hierarchy that the victory had been bought at too high a price, dissent within the dressing room, the very public humiliation of the Team Manager, damage to the reputation of English cricket abroad and the near breakdown of relations between two friendly countries. But such was the popularity of Jardine that the M.C.C had little choice but to reappoint him as Captain for the forthcoming Series against the West Indies.

The touring West Indies Team had obviously done their homework and focussing upon their great fast bowler Learie Constantine they now adopted Bodyline themselves. Jardine reciprocated but having to witness the brutality and negativity of Bodyline first hand saw both the M.C.C and the British crowds begin to turn against him.

Harold Larwood was summoned to a meeting with the Committee of the M.C.C where he was asked to sign letter of apology to the Australian Cricket Board for his bowling on the previous Ashes Tour. Neither Jardine nor the Team Manager Pelham Warner had been asked to sign similar letters and Larwood refused to do any such thing making it plain that he had only been carrying out the instructions of his upper-class Captain who had been appointed by them. He was then curtly informed that his retention in the England team was dependent upon him signing the letter. He refused, and never played for his country again.

Jardine was retained as England Captain for the tour of India but only because the M.C.C in the wake of the Ashes had become sensitive to criticism and were aware that he was still being lauded in the press as a sporting hero.

The tour of India was to be another Series mired in controversy as Jardine’s use of Bodyline caused outrage and on one occasion a riot even ensued. It now seemed apparent to everyone that Bodyline which had been devised to stop one man had now become his means to secure victory.

Pelham Warner had already told them that he did not wish to see Jardine retained as Captain and some of the Australian players had clearly stated that they would not play against a team which had Jardine in it let alone leading it. Fearing that he was about to be sacked Jardine resolved the M.C. C’s quandary for them by resigning. Indeed, he not only relinquished the Captaincy but retired from First Class Cricket altogether. With Jardine gone, in 1935 changes to the rules of the game saw the use of Bodyline effectively banned.

Following Jardine’s retirement, which was seen by some as a mea culpa, further criticism of Bodyline fell squarely on the shoulders of Harold Larwood who along with Bill Voce were still employing it in County Games for Nottinghamshire.

Believing that he had never received due recognition for his achievements in Australia and that he had been unfairly singled out for blame by the Cricket Authorities in England in 1950 Harold Larwood emigrated a bitter and frustrated man to of all places, Australia.

He was to remain loyal to his old Captain, Jardine and would never join in the rising chorus of criticism against him though he would often say that he worked him bloody hard. His most prized possession was a silver ashtray that was a gift from Jardine with the inscription To Harold for the Ashes from a grateful Skipper. Harold Larwood, died in Randwick, New South Wales on 22 June 1995, aged 90.

Douglas Jardine who had Captained England in three successful Series and had finished his First-Class career with a batting average of 48 was to be effectively ostracised from cricket though future England failures were to see his Captaincy viewed more kindly.

After serving with distinction in World War Two where he was evacuated from Dunkirk barely escaping with his life, he was to work in various jobs including as a cricket correspondent and journalist. He died in Switzerland on 18 June 1958 of lung cancer, aged 57.

Following the controversial Bodyline Series Don Bradman was to go from strength-to-strength. In 1934, he was a pivotal member of the Australian Team that regained the Ashes in England and of the teams that retained them in ‘36 and again in ‘38. Indeed, during the 1938 tour of England he was to hit 13 centuries in 26 Innings at an average of 115.66, the highest ever set in England. But his greatest triumph was yet to come.

In 1948, though his own powers were visibly on the wane he captained the Australian Team to England that was too become known as the Invincibles. In the 31 First Class Matches they played they won 23 drew 8 lost 0 and Bradman was to prove every bit as ruthless in his pursuit of victory as Jardine had been grinding his opponents to defeat even after victory had been all but assured.

They were to thrash England in the Ashes Series 4-0 with Bradman’s finest moment coming in the Headingly Test Match when on the final day he hit 173 not out in a partnership with Arthur Morris (182) when the 404 runs required to win were scored in just 342 minutes.

During the tour Bradman was to hit 11 centuries and score at an average 89.92 and coming into the Final Test at the Oval he needed to score just 4 runs for a career Test average of over 100.

Bradman, who had announced beforehand that he intended to retire and that this would be his final ever Innings walked to the crease to a rapturous reception but at the age of 40 his reactions had slowed, and he had shown himself to be vulnerable early on.

As the crowd waited expectantly for history to be made Bradman was clean bowled second ball by the leg-spinner Eric Hollies for a duck and returned to the Pavilion in stunned silence. The world’s greatest ever batsman had finished his Test career with an average of 99.94.

After his retirement Bradman became a journalist and broadcaster, Test Selector and very successful cricket administrator but even with the passage of time he could not bring himself to forgive Jardine and when on his deathbed he was asked to pay tribute to his old adversary he declined.

Donald Bradman died on 25 February 2001, aged 92, in the manner he had lived as Australia’s sporting icon.

Bodyline remains controversial to this day yet at no point were the rules of the game infringed nor were any Australian players seriously hurt when the leg-side field was deployed.

The fact is that Australia had unearthed a batting phenomenon unlike any seen before or since and in response England had found a man who believed he knew how to reduce his effectiveness, and he succeeded.

Many Australians believe to this day that Jardine set out to deliberately intimidate and injure the batsmen at the crease, and they may be right, but their downfall was as much the result of their inability to play the devastatingly fast, short-pitched deliveries of Bill Voce and Harold Larwood in particular, as any tactics employed by the England Captain.

Douglas Jardine’s Ashes success was to be England’s last for eighteen years as once again Bradman batted team after team to defeat.

He was a colossus who had no peer and could not be prevented from dominating world cricket. Until Douglas Jardine that is, a man forced into early retirement who has since become one of sport’s most enduring villains.

Tagged as: Miscellaneous, Modern

Share this post: