Bonaparte's Retreat from Moscow

Posted on 13th April 2021

By 1812, much of Europe lay prostrate at the feet of the French Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte. Indeed, he bestrode the continent like a colossus and where he had not conquered, he had forced those who opposed him to yield to French hegemony. He had defeated his enemies Austria, Prussia and Russia time and time again; he had captured both Vienna and Berlin, created puppet-States in the Low-Countries, Poland and Italy and had occupied the Iberian Peninsula. He appeared invincible but protected by the English Channel and the Royal Navy, Britain alone refused to yield and remained a thorn in his side.

Napoleon Bonaparte was a Corsican of Italian descent who had a meteoric rise to prominence as a result of circumstance, unbridled ambition and no little opportunism.

He first established his reputation as an artillery Officer during the Siege of Toulon in July 1793, when his mastery of the situation taking the high ground and then bombarding the ships in the harbour saw the English Fleet threatening the city to withdraw. As a result of his actions, he was promoted to the rank of Brigadier-General but the fall of the Revolutionary Government a year later led to him being arrested and imprisoned but he was soon released.

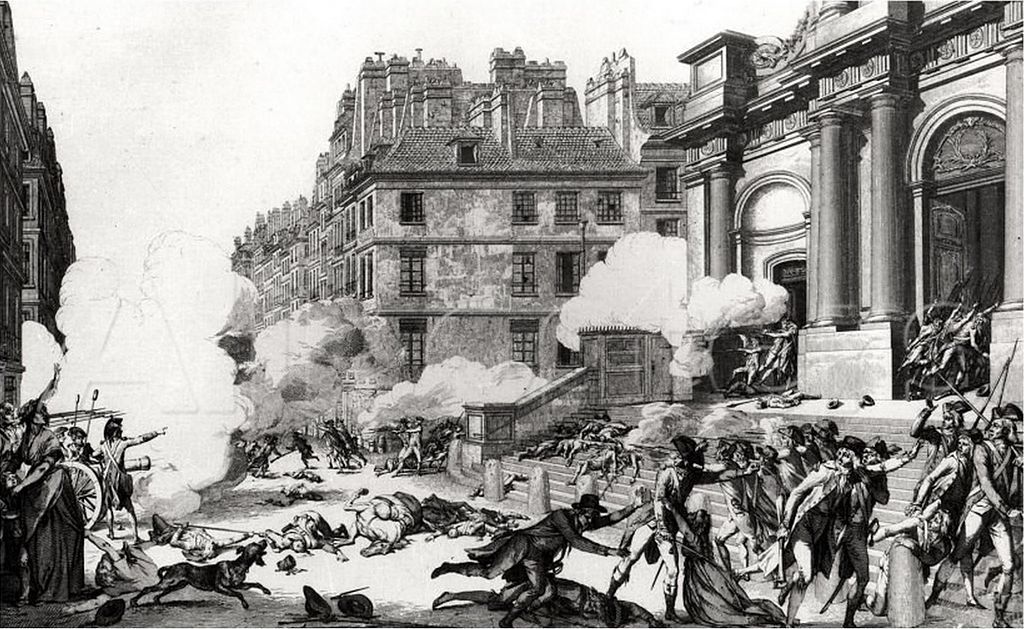

On 5 October 1795, he was called upon to put down a Royalist insurrection in Paris which he did ruthlessly leaving around a thousand of the counter-revolutionaries dead from what he later claimed was little more than a whiff of grapeshot.

In March 1796, he fought a brilliant lightning campaign against the Austrians in Italy that left the country effectively under French control. It seemed that nothing could stop Napoleon’s rise to power, and he was a man with big plans.

He believed that the invasion and occupation of Egypt, a long time French obsession, would provide a route to India thereby threatening Britain’s dominance there. It was a bold and ambitious plan, and he used his reputation as France’s ablest military commander to convince the ruling Consulate in Paris to provide him with an Army that in turn would be supported by the French Fleet.

On 1 July, he landed unopposed at Alexandria and a few weeks later defeated the Egyptian Mameluke Cavalry at the Battle of the Pyramids. But it was to be a short-lived triumph for a month later on 1 August the British Admiral Horatio Nelson utterly destroyed the French Fleet at the Battle of the Nile - Napoleon’s dream of a French Middle East Empire and access to India lay in tatters.

Constant harassment by the Egyptian Army meant that he was forced to continue the campaign even though a breakout of the plague had decimated his forces and at the Siege of Jaffa his frustration boiled over when he had 1,400 prisoners taken to a nearby beach and bayoneted to death. It was an incident that revealed a hitherto unseen cruel and capricious streak to Napoleon’s character.

Aware that political events were moving fast in Paris, Napoleon boarded a ship bound for France leaving his army to its fate. It wasn’t to be the last time he would do this.

Despite the failure of his campaign in Egypt he returned laden with treasures and was therefore able to present it as a glorious triumph and by early 1800 he had manoeuvred himself into the position of First Consul, or the most powerful man in France. Later that year he defeated the Austrians at the Battle of Marengo and a string of further victories soon followed.

The little-known junior Officer from Corsica had become a French national hero and on 2 December 1804, in a ceremony at Notre Dame Cathedral he would snatch the Crown from the Pope’s hands and anoint himself Emperor.

As triumphant as he was Austria, Prussia and Russia did not willingly accept French dominance and needed little encouragement to ally with one another to oppose him. That encouragement and the money required to fight would invariably come from Britain, a country that except for the brief Peace of Amiens from March 1802 to May 1803 never came to terms with Napoleon.

Britain did not have the resources to oppose Napoleon on the Continent and so instead utilised its economic muscle to pay the other powers to fight on its behalf with what became known as “Pitts Gold” after the British Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger.

As a result of “Pitts Gold” various coalitions were formed, most came to nothing or ended in inglorious defeat, but it meant that Napoleon was almost constantly at war. It drove an increasingly frustrated French Emperor to plan for the invasion of Britain determined to eradicate this stubborn and annoying “Nation of Shopkeepers”.

As his army gathered at the port of Boulogne the French Fleet set sail for the West Indies in the hope of drawing the British Navy away from the Channel. At first the plan appeared to have succeeded and the Channel was free to cross but the French Army had not made adequate preparation and they were short of boats.

The delay was to prove costly for Admiral Nelson realising that he had been duped set sail for Britain and when the two navy’s which had been shadowing one another clashed on 21 October 1805 off Cape Trafalgar the French Fleet was destroyed and Napoleon’s hopes of invasion dashed.

Encouraged by Nelson’s victory and hoping to take advantage of the French Army’s absence Austria and Russia hastily formed the Third Coalition. Learning of this Napoleon acted fast and decisively abandoning Boulogne and taking his Army East. He defeated the Austrian Army at the Battle of Ulm and on 2 December 1805 routed the combined Austrian and Russian Armies at the Battle of Austerlitz. It was his greatest triumph, and he went onto occupy both Vienna and Berlin. There was now no question who ruled in Europe, and in celebration of his great victory he built the Arc de Triomphe in Paris.

William Pitt the Younger died not long after hearing of the news it was said of a broken heart; but he also died in the knowledge that he had left Britain secure, for the time being at least. Napoleon however remained determined to bring Britain to its knees but with his plan of invasion in tatters and with the remains of the French Fleet still blockaded in port a new way had to be found. So he devised a system that would strangle the life out of the British economy by cutting off its trade with the European Continent.

The Continental System as it became known would prevent Britain from re-exporting its colonial goods to Europe and in November 1806 the so-called Berlin Decrees declared that no British ship or any other leaving British shores would not be permitted to dock in any European port under direct French control, jurisdiction or influence. In March 1807, the Milan Decrees extended this to foreign ships known to have docked in a British port.

The British responded by passing the Orders in Council which declared the Royal Navy would divert all ships trading with Europe to British ports where they would be made to pay a heavy tax on their cargo before being released. Even so, despite Britain’s domination of the seas she was effectively under blockade. But for Napoleon’s system to work the countries of Europe had to adhere to it and not all did.

Portugal, for whom Britain was a vital trading partner refused to comply with the Continental System. Concerned that Portugal’s example might encourage others to do likewise in the spring of 1807 with the support of Spain he invaded.

The presence of French troops on Spanish soil proved deeply unpopular with the people as also did the Monarchy’s support for the invasion of their Iberian neighbours and once it became clear that the Spanish King Charles VI could not guarantee the support of his people Napoleon had him deposed in favour of his brother, Joseph Bonaparte. It was to prove a disastrous strategic error.

In July 1808, the Spanish people rose in revolt and the following month Britain dispatched an Army under Sir Arthur Wellesley, the future Duke of Wellington, in their support. The ensuing Peninsula War was to last seven years and tie down 300,000 of Napoleon’s best troops. He was to refer to it as his “Spanish Ulcer later declaring - “That unfortunate war destroyed me.”

Following his crushing victory at Austerlitz and the occupation of Vienna the Austrians succumbed but the conflict with Russia continued. On 14 June 1807, he defeated the Russians once again at the Battle of Friedland and pursued them east but with much of Western Europe under his control it was not in his interest to continue the struggle - he wanted peace.

With the opposing armies on opposite banks of the River Nieman on 7 July the French Emperor and the Tsar of all the Russia’s met on a raft midstream. It was by all accounts a cordial meeting with the impressionable young Tsar appearing to be in awe of Napoleon’s genius. More formal discussions took place over the following two days in the nearby town of Tilsit where they agreed to effectively divide Europe into spheres of influence emasculating Russia’s one time ally Prussia and dividing Poland between themselves.

Tsar Alexander also agreed to enforce the Continental System and the peace allowed Napoleon to release troops for the continuing struggle in the Iberian Peninsula, secure his Eastern borders and gather his strength to oppose any future Coalitions formed against him.

For the first time it appeared that Napoleon had a genuine ally who had not been bullied into submission, but things were not quite as they seemed.

Tsar Alexander may have appeared genuine enough but many at the Russian Imperial Court and among his senior Commanders were sceptical. It had been evident to many present at the negotiations that despite the cordial atmosphere prevailing Napoleon intended the Tsar to be the junior partner. Yet despite having been defeated in battle The Motherland remained undefiled and many at the Royal Court resented their subordinate role. The Tsar’s Generals also feared the presence of so many French troops on Russia’s Western border. But had not Napoleon had told the Tsar: “What is Europe, if it is not you and I?” He was aware that Alexander was in awe of him, and his words had been carefully chosen.

Their personal relationship appeared strong and for four years the alliance remained intact, but Alexander had ambitions of his own; but if Russia was to compete with French mastery in Europe it would have to modernise and to do that it needed British manufactured goods.

In 1811, it broke with the Continental System and without Russian compliance the continuing blockade of Britain would prove ineffective. Fearing French retaliation Tsar Alexander mobilised his forces for a pre-emptive strike on Poland.

Once again Napoleon was swift to respond to the threat – he would invade Russia first even though he had been warned that to do so would prove a logistical nightmare but then it was not his intention to occupy the country or even capture Moscow but rather to lure the Russian Army into a single engagement that would decide the issue.

Staging posts and supply depots were established throughout Poland but Napoleon’s armies had traditionally lived on the land they passed through and it was expected that they would do so again.

By the summer of 1812, Napoleon had raised an army numbering some 640,000 men, the largest ever seen on the Continent and it was a polyglot force gathered from throughout his European Empire. There were 300,000 French, 115,000 Germans, 98,000 Poles, 57,000 Italians, 34,000 Austrians, 10,000 Swiss, 4,800 Spanish, 3,200 Croats, 2,000 Portuguese, and others. Napoleon believed that the mere presence of his Grand Armee massing on the borders of Poland would bring the Tsar to heel but when it did not on 24 June 1812, he ordered 420,000 men with a baggage train of more than 6,000 wagons to cross the River Niemen. The remainder of his army was left to protect the supply depots and defend the Polish border - the invasion of Russia had begun.

The Grand Armee set off at pace determined to bring the Russians to battle as soon as possible and within days they descended upon their Army Headquarters at Vilnius in Lithuania only to find it abandoned and its stores burned. The Russian Commander Barclay de Tolly had decided the city indefensible and ordered a hasty retreat.

Napoleon continued to force march his army but apart from a few minor skirmishes he could not bring the Russians to battle. They simply refused to fight and as his Grand Armee advanced further and further into the Russian heartland maintaining discipline became a problem.

In the searing heat of a Russian summer Napoleon’s troops began to suffer from sunstroke while contaminated water caused both dysentery and typhoid fever. The vast, featureless, and seemingly endless Russian plains was also the cause of a melancholia that saw some troops take their own lives.

But Napoleon’s great dilemma was how to feed his vast army for as the Russians retreated, they adopted a scorched earth policy burning and destroying everything in their wake and he had to depend upon supplies reaching him from the depots he had established in Poland and more than 100,000 troops had to be left behind on the Grand Armee’s advance to keep open lines of communication and these were under constant attack from Cossack raiders.

The Grand Armee was threatened with starvation, and it was hampered on its advance by roads that were little more than dirt tracks, rock hard and difficult to traverse which following a downpour of rain would often turn into a quagmire. Troops now began to desert, and the Russian countryside was soon littered with small bands of French soldiers who had become little more than bandits.

Despite all the problems, Napoleon still believed that the sight of his Grand Armee marching through Russia virtually unopposed would force the Tsar to sue for peace but Alexander who had been so dazzled by Napoleon at their meeting five years earlier, had come to hate the Emperor who had dared to invade his country and the longer the invasion continued the more determined he became to resist it.

Barclay de Tolly’s continued retreat in the face of the Grand Armee had lured Napoleon far deeper into Russian territory than he had ever intended to go but his reluctance to fight would eventually lead to his dismissal. He was replaced by the 67-year-old Marshal Mikhail Kutuzov.

By no means a great strategist or tactician and certainly not when compared to Napoleon he was nonetheless competent, stubborn, obdurate and personally courageous. He could see the sense in Barclay de Tolly’s strategy and for a time continued the retreat, but he knew that at some point the Russian Army would have to turn and confront its enemy.

The two armies first clashed at Smolensk on 16 August, but Kutuzov was quick to break off the engagement. He was looking for the right place to make a stand and so continued the retreat until he found what he thought was a good defensible position at the small village of Borodino some 75 miles west of Moscow. Here the Russian Army would at last defend the Motherland.

The Battle of Borodino began at 06.00 on 7 September 1812, and the fighting that would continue until darkness descended upon the battlefield would be relentless, bloody and murderous.

The Russian left flank had been dangerously exposed in the early exchanges and was to leave them in a perilous position throughout the rest of the day; Napoleon was quick to exploit the advantage and utilised his artillery brilliantly as it pounded and raked the exposed Russian lines cutting swathes through its ranks. Kutuzov was willing to endure the punishment however, his primary concern was to preserve his army intact and deny Napoleon the decisive victory he sought. So, despite being outnumbered and taking heavy casualties he refused to commit more than a third of his available force including most of his artillery to the battle. Those already engaged would have to do the fighting alone.

The Russian strength lay in the renowned stubbornness of their infantry and the dash and fighting spirit of their cavalry. Indeed, so outmatched was the French cavalry that Napoleon refused to commit them to battle without infantry support. The Russians had also constructed a series of defensive redoubts in direct line of the French advance.

In the confusion of battle and with their vision impaired by gun-smoke and dust the French infantry attacked and took these redoubts only to lose them again moments later as the Russians counter-attacked bayonets fixed.

The battle swung to and throe as the redoubts were won, lost, and won back again and the fighting became increasingly desperate as the Russian lines began to creak under the strain. This was the moment for decisive action, but Napoleon hesitated. With all his forces already committed to the battle he had only one option remaining, the 16,500 men of the Imperial Guard the cream of his army never before defeated in battle. Should he commit them now and they fail him then not only the battle, but the war was lost. He chose not to do so, and instead of a victory secured both sides withdrew from the fighting battered, bleeding, and exhausted. During the night the Russians retreated from Borodino leaving the French in possession of the field.

The battle had been a tactical victory for the French but a strategic defeat, and the cost of the fighting had made it at best a pyrrhic victory. In ten long hours of savage fighting 28,247 French soldiers and their allies lay dead, dying and wounded. The Russians had also suffered grievously with more than 35,000 men being left on the field, but their army had withdrawn intact just as Kutuzov had intended.

Before the battle Napoleon had remarked, “If I take Moscow the World will be astounded.”

Now the road to that great city lay open but Kutuzov who had never expected an outright victory but merely intended take as greater a toll on the French as he could was prepared to abandon it. The Russian Army had survived to fight another day and Kutuzov knew that it could be reinforced, replenished and re-armed. He also knew that Napoleon’s Army could not.

Borodino had been chastening experience for both armies and Napoleon would later recall, “Of the 50 battles I have fought, the most terrible was that before Moscow . . . the Russians can rightly call themselves invincible.”

On 14 September, Napoleon entered Moscow, the spiritual heart of Russia even if its political capital remained at St Petersburg. By now his main strike army of 296,000 men had been reduced by starvation, disease and battle to less than 96,000. Even so, he expected the formal surrender of the city but instead found it abandoned and stripped of all supplies with the only people remaining it seemed foreigners and criminals.

TThat same night the burnings started and with two-thirds of Moscow’s houses made of wood the city was soon ablaze. Suspected arsonists were rounded up and shot but it was too late the damage had already been done.

The Russians maintained a presence in the area around Moscow perhaps as many as 100,000 men but more significantly their army had not retired east as expected but had positioned itself west of the city and in the path of any future French retreat.

Deprived of food, shelter and wood with which to warm themselves his soldiers soon began to despair while Napoleon was simply bemused by the Tsar’s unreasonableness. He had marched his army into the heart of Russia, brushed aside the Russian army and captured Moscow – could he not see that he had been defeated?

He wrote to Alexander demanding he come to terms if not to prevent unnecessary bloodshed, then out of friendship and the mutual respect they once shared: “I appeal to the last remnant of your former sentiments toward me.” He received no reply, instead the Tsar remarked to a Courtier: “It is either he or I we can no longer reign together.”

For four weeks Napoleon remained in Moscow uncertain what to do until on 12 October he accepted the inevitable and ordered his army to abandon the city; the retreat from Moscow had begun but his dithering as the city burned down around him was to prove fatal.

The withdrawal began in reasonably good order, the weather was chilly but clear and it was still possible to be warmed by the late autumn sunshine. But many guns and much materiel had to be left behind as the horses required for the artillery and baggage train had already been eaten. With the main problem finding food with which to feed his army Napoleon ordered that it proceed on a more southerly course to forage for supplies but following a confrontation with the Russians at Maro-Jaroslavetz it was forced to divert and travel across a countryside already ravaged by its previous advance. It also found itself constantly harassed by brutal and merciless Cossacks who attacked isolated units while Russian peasants regularly murdered stragglers for loot.

Also, with the Russian Army following close behind and with his army in no fit state to fight a pitched battle, Napoleon had little room to manoeuvre. His only option was to keep going.

On 6 November, the first snows fell and as the winds picked up and gales began to blow across the barren landscape half-starved, freezing and snow-blinded men began to die in their thousands.

By 24 November temperatures had plunged to -25 degrees, and they would soon reach -30 and it was so cold, the snow blizzards so constant and the landscape so flat and featureless that men already weakened by hunger unable to build shelters simply huddled around campfires where they yearned for food but even more so for sleep; but as exhausted as they were to sleep was a fearful prospect as so many never woke up again, sentries froze to death at their posts, soldiers murdered one another for a piece of warm clothing and military discipline began to break down. An advisor to Napoleon Bonaparte, General Armand de Caulincourt recalled:

“Once these wretches fell to sleep they were dead but the drowsiness engendered by cold is irresistibly strong. Sleep comes inevitably and to sleep was to die. I tried in vain to save as many as I could but they begged me to leave them alone and let them sleep. I saw this happen to thousands of individuals and the road was covered with their corpses.”

Kutuzov used his Cossacks to good effect as isolated French units were attacked and cut to pieces as they huddled together for protection.

By early December the remnants of the Grand Armee had reached the River Berezina where Marshal Ney, who would earn the plaudit “Bravest of the Brave” during the retreat, fought a desperate rearguard action while the rest of the army crossed the soon to be frozen river on hastily improvised bridges and those few places where it could be forded.

As the Russian Army closed in the bridges had to be burned in haste leaving more than 10,000 stragglers behind to be killed by marauding Cossacks and when the river finally defrosted the following spring some 12,000 were recovered from its icy waters.

Even in abject defeat the Grand Armee continued to be harassed by the Russians, they had been ordered to do so until the last Frenchman had been removed from the sacred soil of Mother Russia.

On 6 December, Napoleon announced that pressing political matters at home meant he had to return to Paris immediately and so just as had done in Egypt ten years earlier he abandoned his army to its fate. The man he left in command Marshal Joachim Murat likewise made his excuses a few days later and also abandoned the army.

For another three weeks the Grand Armee fought on without its Emperor and any effective command structure. Short of ammunition, bedraggled, and close to death what had been a war had long ago become a mere struggle for survival and some Regiments now burned their Standards and Eagles to prevent them falling into enemy hands.

By mid-January the last French soldier had left Russian soil and of the 420,000 men who had initially been committed to the invasion fewer than 28,000 frost-bitten, malnourished, scarecrows ever returned to France only 4,000 of whom had been with Napoleon on the day he entered Moscow.

In just six months of a bitterly fought campaign the aura of invincibility that had for so long sustained Napoleon Bonaparte had been utterly destroyed on the endless plains of the Russian hinterland just as the ambitions of a similar man of destiny would be destroyed 130 years later.

At Fontainbleu on 4 April 1814, less than two years after his once triumphant Grand Armee had first crossed the border onto Russian soil and with Paris under enemy occupation Napoleon Bonaparte abdicated.

He would turn up once more as the proverbial bad penny so often does and more blood would be spilt as a result, but his time had passed.

Tagged as: Miscellaneous, War

Share this post: