Burke and Hare: The Body Snatchers

Posted on 14th April 2021

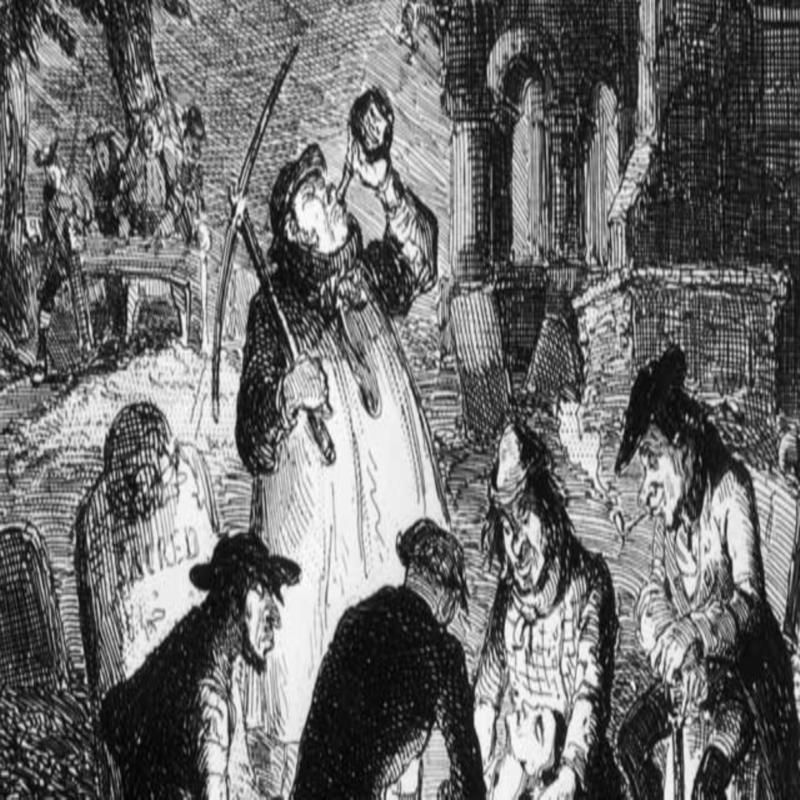

In the dim and dank backstreets of nineteenth century Edinburgh an illicit trade was flourishing, it was a trade in dead bodies. Grave-robbing was hardly unknown at a time when the custom was to bury the recently deceased in their finest clothes and favourite pocket-watch or similar item of jewellery. It provided rich-pickings for those willing to defile the bodies of the dead but the stealing of corpses for reasons of forensic science was a relatively new phenomenon, and the fresher the cadaver the better the price.

It was a grim trade that was to spawn two of the most notorious killers in history, William Burke and William Hare both of whom though they operated in Scotland were in fact Irish.

William Burke was born in the town of Urney in County Tyrone around 1792 and is believed to have been a relatively well-educated man who had served in the British Army. He was also married with two children but for some reason in 1817 simply abandoned his family and fled to Scotland where living in Edinburgh he struggled to make a living doing various menial jobs before finding regular work on the Union Canal. Not long after moving to the city he went to live with Helen MacDougall, a prostitute.

William Hare was born in Newry around 1800 and it seems unlikely that two men knew each other in Ireland but met working together on the Union Canal. In 1826 he married the widow of his landlord, Margaret Laird.

The custom of burying the recently deceased with their most valued possessions made graveyards a magnet for the so-called Resurrection Men in search of easy pickings. Indeed, so common had grave-robbing become by the 1820’s that it was not unknown for families to stand guard at the graveside of their deceased relative until they were sure that the bodies had decomposed when they would dig down open the coffin and remove any valuables that may have been buried with them. It is likely that Burke and Hare were already experienced grave-robbers when in late 1827 a tenant at Margaret Laird’s Lodging House unexpectedly died still owing rent.

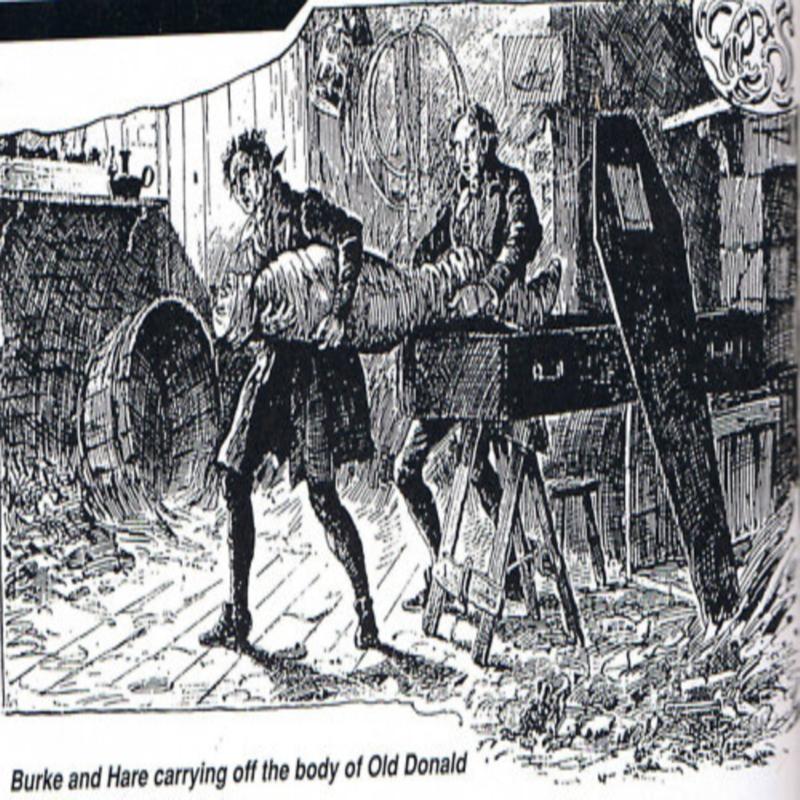

Burke and Hare packed his body in a box and took it to the residence of the ambitious Edinburgh surgeon and anatomist Dr Robert Knox. Fresh cadavers were at a premium in Edinburgh and Dr Knox was happy to pay them £7’10s for the corpse. Neither Burke nor Hare felt morally compromised by what they had done, they were after all merely retrieving money the dead man owed.

It soon dawned on them however that this was a much easier way of making money than going out in the dead of night to dig up the recently departed from the frozen ground. Or indeed the back-breaking work they were required to do for a pittance on the Union Canal. This was also the most they had ever been paid for a corpse and they realised that the sooner they got the corpse to a surgeon the more they were likely to be paid – their minds turned to murder.

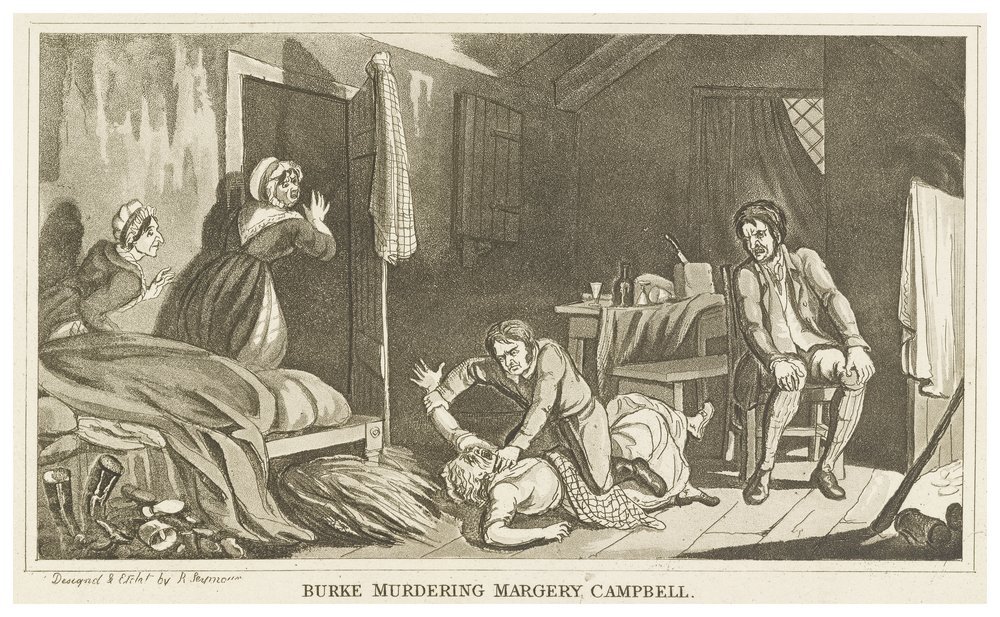

Working from Margaret Laird’s Lodging House in Tanner’s Corner, West Point, they first murdered a sick tenant Joseph Miller who they got drunk with whisky before suffocating and this soon became their preferred modus operandi.

In February 1828, they lured an elderly woman Abigail Simpson, to the house when again she was made to drink whisky and then suffocated. It was important that the bodies remained unmarked to avoid suspicion.

Burke and Hare were soon making more money than they had ever made in their lives, and they told Dr Knox that they could provide him with a regular supply of fresh cadavers but that it must be done on a no questions asked basis. Dr Knox agreed to turn a blind eye.

Both Margaret Laird and Helen MacDougall were willing participants in their respective partner’s work. They would invite women into the house where they would provide them with copious amounts of alcohol before calling in one of the men to finish them off. Most of their victims were prostitutes. Burke would also prowl the streets of Edinburgh Old Town in the dead of night looking for potential victims often lurking outside Police Stations waiting for intoxicated women to be taken for a night in the cells. He would then get them released into his custody on the guarantee of their future good behaviour, two hours later they would be delivered up dead to Dr Knox.

Burke and Hare’s victims were beginning to mount up including an entire family of grandmother, daughter, granddaughter and grandson.

The people they murdered rarely seemed to be missed and Dr Knox who always paid up on delivery was eager for more. It was all too easy, they were becoming complacent, and their luck was about to run out.

During one of Burke’s nocturnal prowls, he came across two well-known local prostitutes Janet Brown and Mary Patterson who he invited back to the Lodging House. Janet Brown left when she became concerned at Burke’s increasingly aggressive behaviour. Mary Patterson remained, however. A few hours later her body turned up on Dr Knox’s operating table. But among his students were some of her former clients who were surprised to say the least and their suspicions were further aroused when a little later Burke murdered a popular local retard known as Daft Jamie.

This was the second time in a few days that a well-known local character had turned up on Dr Knox’s operating table and some of his students now questioned him as to where exactly he was getting these bodies from. Knox refused to answer and denied that the body on the slab was that of Daft Jamie but merely of someone who looked like him.

In December 1828, almost a year into his murder spree Burke invited a woman he had befriended, Marjory Docherty, to stay in the Lodging House. But first she would have to wait for the current lodgers James and Ann Gray to move out for the night. When they returned the following day Burke told them not to go near the bed which was a foolish thing to say for the first thing she did was to check underneath where to her horror she found the body of Marjory Docherty. She fled the house and with her husband made for the nearest Police Station.

Realising what was happening Helen MacDougall pursued them down the street begging them to stop, even offering them £10 not to tell of what they had seen but they refused.

By the time the Police arrived at the Lodging House a few hours later the body had been removed and upon being questioned regarding the whereabouts of Marjory Docherty, Burke told them that she had left the Lodging House at 7 am that morning. When Helen MacDougall contradicted him by saying that she had in fact left the previous evening they were both promptly arrested, and the Police soon made the connection between Burke and Dr Knox. When they visited the surgeon later in the day, they found the body of Marjory Docherty already lain out on his slab.

The Police now also arrested William Hare and Margaret Laird who were known to be associates of Burke and MacDougall and to have worked for Dr Knox.

When she heard of the arrests Janet Brown went to the Police and confirmed that some of the clothing found at the scene had belonged to her missing friend, Mary Patterson.

The Police considered the evidence against Burke, Hare, and the others too flimsy to guarantee a conviction for murder but having identified the shy and nervous Hare as the weaker of the two men and the one least likely to have committed the murders (though he was certainly guilty of at least one) the Lord Advocate Sir William Rae offered him immunity from prosecution if he would turn King’s Evidence and testify against Burke. He did not need to be asked twice.

William Burke was to be convicted on 16 counts of murder but at his trial he testified that Dr Robert Knox had known nothing of the origin of the cadavers he was provided with and so despite having already been convicted in the court of public opinion he was never charged.

Believing that justice had been served in the conviction of Burke neither Margaret Laird nor Helen MacDougall ever faced prosecution though they were forced to flee Edinburgh to avoid the angry mobs set upon lynching them.

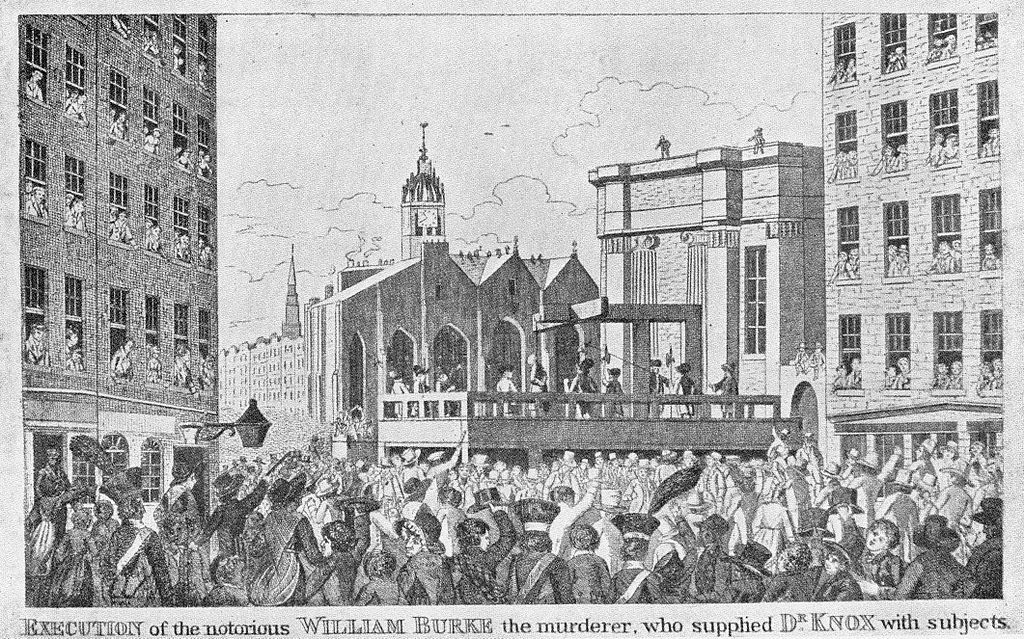

In the days prior to his execution Burke publicly forgave Hare for his betrayal and always a garrulous man talked a great deal to the Catholic Priests he insisted attend upon him throughout his ordeal during which he was said to have wept often and to have been truly remorseful for what he had done. Nonetheless he faced his execution with fortitude.

William Burke was hanged on 29 January 1829, to much fanfare and before a large crowd and his corpse, like that of his victims was dissected for the benefit of the students at Edinburgh’s College of Surgeons – his death mask, skeleton and a wallet made from his tanned skin remain as exhibits in the College Museum.

William Hare was released from custody in January 1829 and left Edinburgh after being attacked in the street and seriously injured. He was last heard of living in Carlisle, blind, penurious and in poor health.

Tagged as: Georgian

Share this post: