Churchill's Darkest Hour

Posted on 9th October 2021

On 9 April 1940, after seven months of inertia often referred to as the ‘Phoney War’ German forces invaded Norway. In doing so they pre-empted Allied plans to do the same but an unwillingness to breach Norwegian neutrality had seen them dither. The Germans who displayed no such scruples had stolen a march and thrown the Allied campaign into confusion.

Despite some isolated successes bad organisation, poor coordination, and a lack of will soon saw the Allied campaign descend into chaos. It was still stumbling towards its inevitable denouement when on 8 May after two days of tense debate in the House of Commons the Labour opposition called for a ‘Division,’ effectively a vote of No Confidence in the Government.

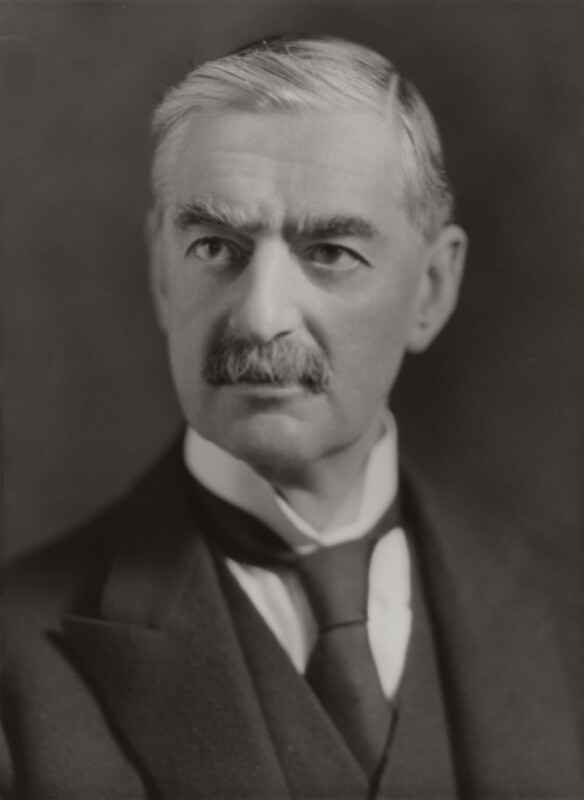

The Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain called upon “my friends in this House to support me” but despite his plea and the comfortable majority he enjoyed he left nothing to chance and imposed a ‘three-line whip’ compelling his fellow Conservatives to support him. He was perhaps wise to do so for the previous two days had seen his Government and their handling not just of the Norwegian campaign but the war in general, savaged from every corner of the House.

The military analysts had had their say, now it was the turn of the politicians.

David Lloyd George, the former Prime Minister who had been at the helm for much of the Great War and such a dominant figure at the Versailles Peace Conference was called upon to speak. Noted for his oration he was at 77 years of age now too often a silent backbencher but those present waited with anticipation nonetheless He did not disappoint:

“This nation is prepared for every sacrifice so long as it has leadership, so long as the Government show clearly what they are aiming at and so long as the nation is confident that those who are leading it are doing their best. I say solemnly that the Prime Minister should give an example of that sacrifice, because there is nothing that can contribute more to victory in this war than that he should sacrifice the seals of office.”

The Conservative Leo Amery, who had previously been in Cabinet, was no less scathing when looking Chamberlain in the eye and quoting Oliver Cromwell, he told him:

“You have sat here too long for any good you have been doing. Depart, I say, and let us have done with you. In the name of God, go.”

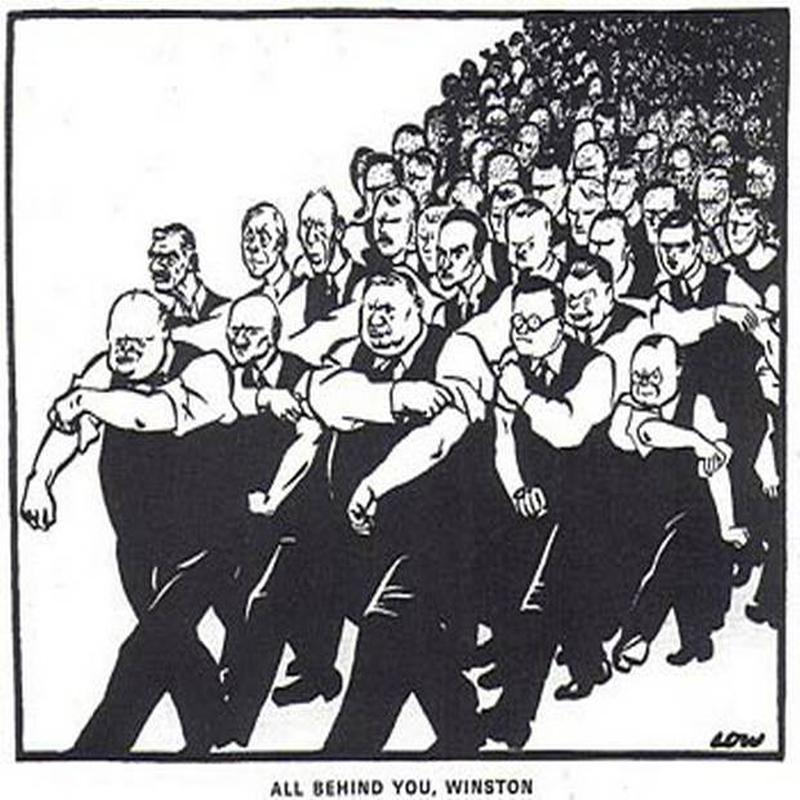

To frequent interruptions and at times howls of derision Winston Churchill wound up the debate with a robust defence of the Government and the person of the Prime Minister denying accusations of timidity and incompetence.

The Chamber had been boisterous and unruly throughout but when it came to the vote the Government won comfortably enough by 281 to 200 but this was misleading and a breakdown of the figures told a very different story with, despite the imposition of the three-line whip, 41 Conservative MP’s voting with the opposition and a further 60 abstaining.

As Chamberlain made his way from the House following the vote, still Prime Minister, it was to shouts of – Go, Go Now! Indeed, the criticism of him had been so sustained and so personal that it had made any prospect of his continuing untenable. Yet even with his authority so undermined he remained reluctant to resign and it was only when the Labour Party leadership refused to participate in a Coalition Cabinet led by him that he felt obliged to do so - but who would succeed him?

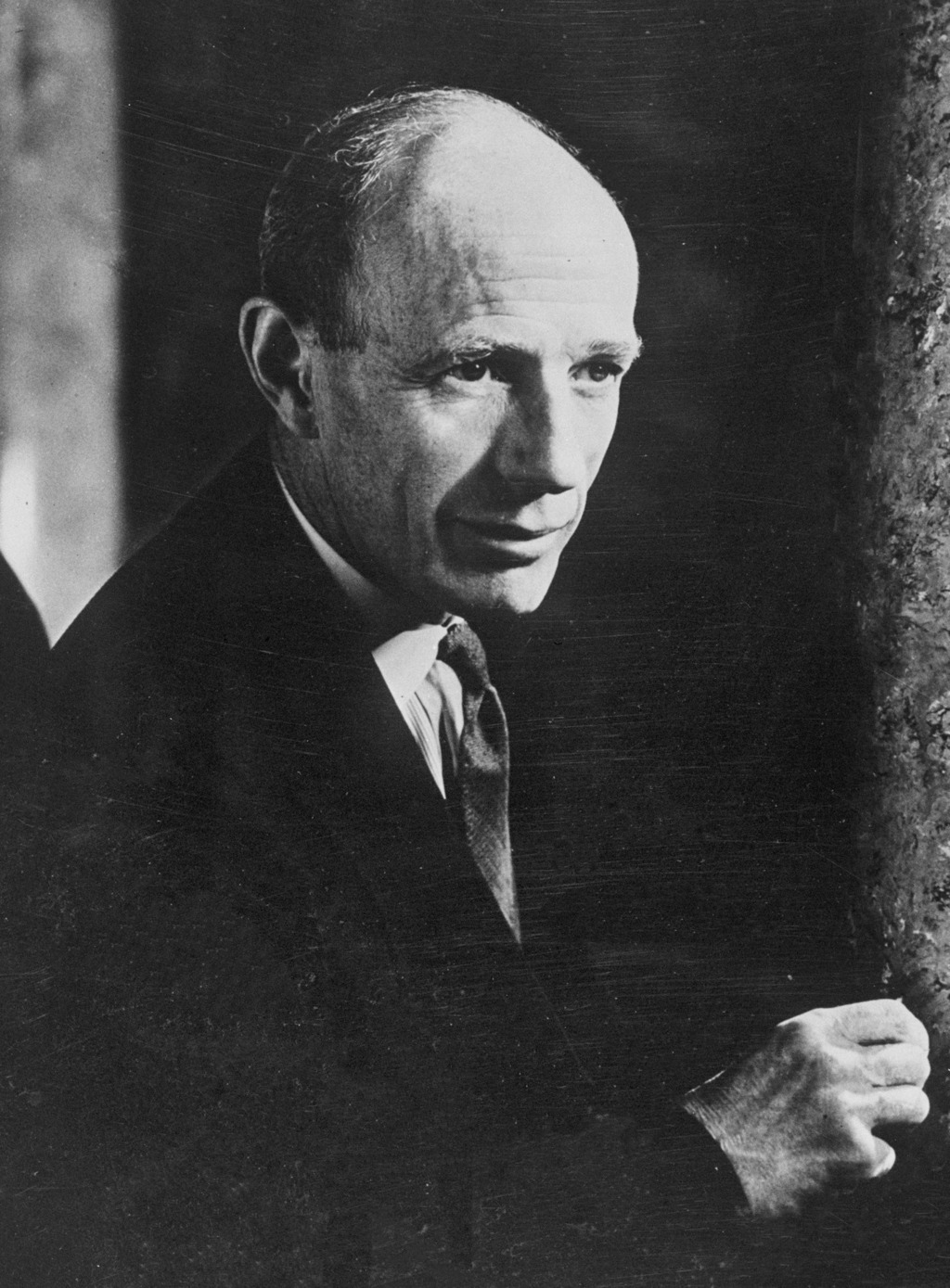

It was expected to be Edward Frederick Lindley Wood, Lord Halifax, his Foreign Secretary and de facto deputy, but as an architect of Chamberlain’s pre-war policy of appeasement it was rumoured that if appointed the Labour Party would be no more willing to work under him than it had been his predecessor. Halifax also had doubts of his own and was reluctant to take up the reins of power. Indeed, it was said that he would turn pale at the very suggestion, and he was to later remark himself that the thought of it made him feel sick in the stomach.

The only realistic alternative to Halifax, however, was First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill, a controversial figure who could a prove divisive figure at a time when unity was required above all else.

To some he was an insightful early critic of Adolf Hitler who had been right in demanding Britain re-arm in the face of the Nazi threat; to others he was a dangerous maverick, a reckless gambler and warmonger who had never been forgiven for his role in the disastrous Gallipoli campaign during the previous conflict. He also had to take his share of the blame for the recent Norwegian fiasco.

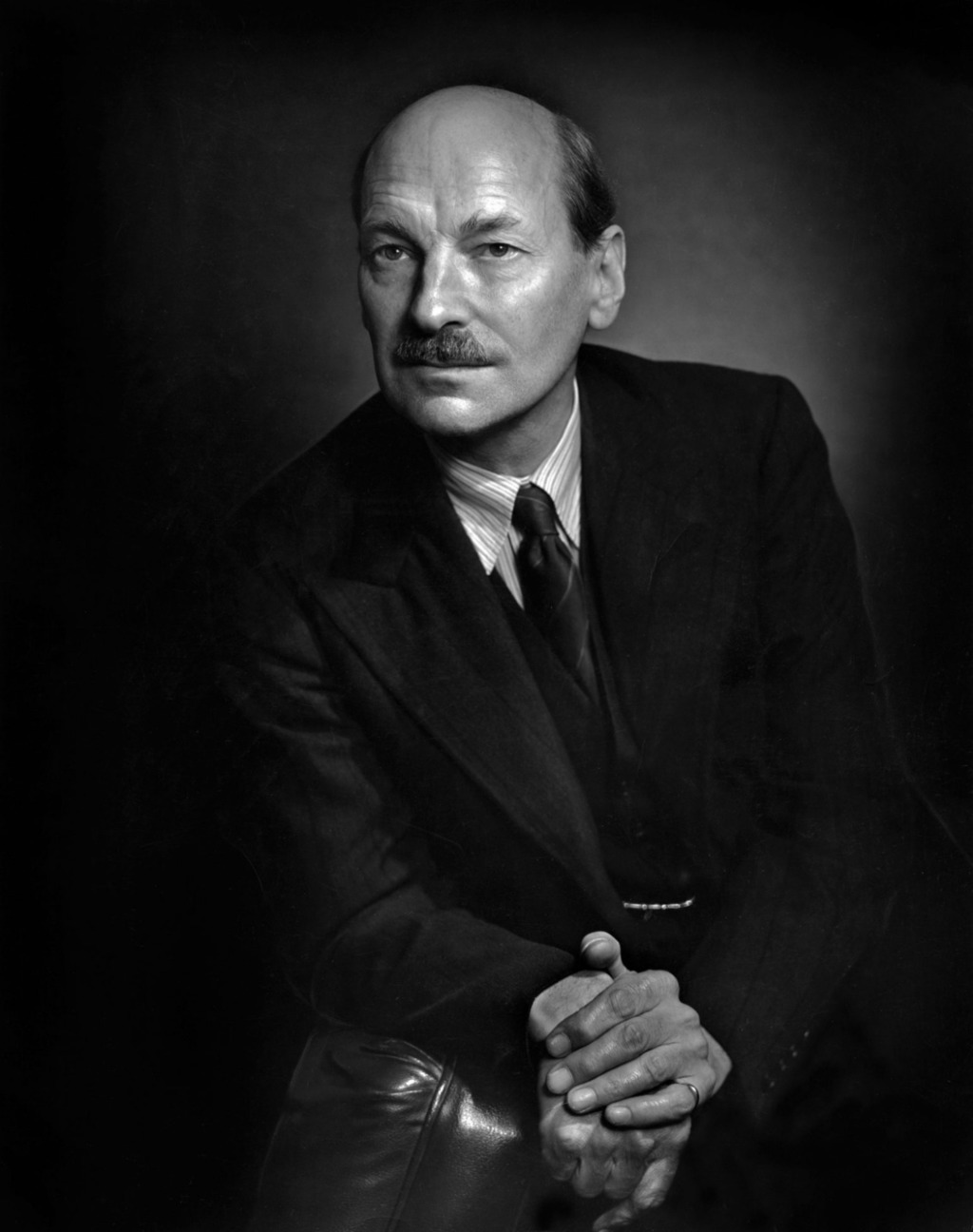

On the evening of May 9, Chamberlain met with the Labour Party leader Clement Attlee and his deputy Arthur Greenwood who confirmed they were unwilling to serve in any Cabinet as long as he remained Prime Minister but might consider doing so under another Conservative.

Upon their departure Chamberlain summoned Churchill and Halifax to tell them of his intention to resign. It was clear that the latter was his preferred choice to succeed him and as he spoke to Halifax about doing so Churchill declined to intervene and instead, remaining silent he turned his back on proceedings and stared out of the window.

Halifax’s lack of enthusiasm for the role soon became clear and fishing for a reason to rule himself out declared that he could not govern effectively from the House of Lords.

The following morning the May 10, Neville Chamberlain journeyed to Buckingham Palace to inform a startled King George VI that not only would he publicly announce his resignation that night but that he should invite Winston Churchill to form a new Government. That same day German forces invaded France and the Lowlands – the Blitzkrieg had begun.

The Allied response to the German attack was both leaden and predictable and there appeared to be a reluctance on the part of the French High Command to commit to battle with the same vigour as they had in the Great War; and so as the German panzers by-passing the Maginot Line swept through the seemingly impenetrable Ardennes Forest, across the Meuse River, and onto Sedan threatening to cut-off the Anglo-French army still entrenched on the Belgium/Dutch border, their response remained confused and uncertain - time was not on the side of the Allies and the situation depreciated rapidly.

On 17 May, just a week after the Blitzkrieg had begun the Netherlands surrendered further undermining Allied plans.

Having lost faith in his French Superiors direction of operations on 25 May Lord John Gort, Commander of the British Expeditionary Force, ignored orders to participate in an intended Allied counterattack south and instead ordered the B.E.F west towards the Channel Ports and possible embarkation on ships provided by the Royal Navy.

To the French his decision was little short of outright betrayal, but it had paved the way for the implementation of Operation Dynamo and the evacuation of the British Expeditionary Force from France.

Restricted to a narrow corridor leading to Dunkirk, which following the fall of Calais remained the only possible port of embarkation the B.E.F and the French Second Army were hemmed in on all sides and a German breakthrough appeared imminent.

On 28 May, Belgium surrendered creating a gap in the Allied perimeter that had to be hastily filled by the small British rear-guard. As the Germans closed in frantic efforts were being made to evacuate as many troops as possible but it was proving painfully slow and no more than 40,000 were expected to be rescued.

As events in France unfolded and the prospect of a humiliating defeat loomed large thoughts of how to respond dominated Whitehall – with the bulk of the British Army left to rot in German prisoner-of-war camps surely an armistice and agreement was the only option, and soon.

On 25 May, Lord Halifax met with the Italian Ambassador Giuseppe Bastianini in London to discuss the possibility of Italy mediating a settlement to the conflict. Surely Signor Mussolini would want to be seen as peacemaker, once he had secured his own slice of the French pie of course.

Halifax was seeking a compromise peace but didn’t commit to anything instead he brought his suggestion before the War Cabinet where he presented it with his wholehearted endorsement. Churchill did not dismiss out-of-hand though he doubted that Mussolini could be anything but Hitler’s stooge.

But then Churchill was in no position to dismiss anything, he had a fight on his hands and not just with the Germans, he had to keep France from making a separate peace while also preserving his premiership at home.

Halifax continued to advocate for mediation in a situation that could only end badly for Britain and its Empire, he insisted. If her liberty and independence could be guaranteed, then a settlement on the Continent would be acceptable to British interests. Churchill disagreed, a German dominated Europe could never be in British interests, and that to prevent such an outcome had been a primary reason for Britain’s engagement in the Great War.

Churchill adjourned the meeting without a decision to meet with the French Premier Paul Reynaud, the news was not good. Reynaud was despondent, the military situation was hopeless and there was little desire among the French High Command to fight on. He would never sign a separate peace he told Churchill, but there were those in his Government who would and he doubted he could survive in his post much longer.

Churchill, who similarly feared being undermined did his best to boost Reynaud’s moral: “We would rather go down fighting than ever be enslaved by Germany,” he told him.

But a pledge of ever greater resolve rings a little hollow when your army its equipment abandoned is being evacuated in some haste from the beaches of a battered and burning coastal town.

A further War Cabinet meeting took place on 27 May, a day that saw only 7,669 men evacuated from Dunkirk with little opportunity it seemed to rescue many more. But Hitler had already issued the order to halt his panzers preventing the Wehrmacht from pressing home its attack. It would provide the breathing space the B.E.F required to withdraw its troops and get them aboard the ships.

There were 9 Inner and Outer Cabinet meetings between the 26th and 28th May, and with the news from France unremittingly bad the pressure upon Churchill increased with each one.

The Inner Cabinet consisting of Churchill, Attlee, Greenwood, Chamberlain and Halifax was where the issues were first aired. Churchill could rely upon the support of the Labour members and for the meeting on the 27th he breached protocol by inviting the Liberal Party Leader Sir Archibald Sinclair, a long-term opponent of appeasement, to attend; but he knew their opinions carried little weight within Conservative Party ranks where his real problems lay. There were many who still vehemently opposed his appointment and he knew sought his removal. If the rejection of Lord Halifax’s proposal to seek an Italian mediated end to the war compelled him to resign and if Chamberlain who supported, it did likewise then his government would fall and his premiership would be a very short one indeed. Chamberlain, he knew remained willing to take up the reins of power once more.

It was not just a case of personal ambition on Churchill’s part, he believed the policy pursued by Halifax would have catastrophic consequences not only for Britain and its Empire overseas but the future of the entire free world.

It was 4.30 in the afternoon, and the second time the Inner Cabinet had met that day. The first had been to discuss the military situation and had broken up having reluctantly agreed that it was bleak and likely irretrievable. Now they would discuss what to do in the likelihood of defeat and the abandonment in France of most of the B.E.F and almost all its heavy guns and motorised transport. Churchill was for continuing the war whether in alliance with France or not and regardless of events. Halifax thought such an option foolhardy at best and again advocated for an armistice to be sought as quickly as possible via a third party (in this case the Italians) and the opening of peace negotiations. He again put before Cabinet the proposals contained in his Reynaud Memorandum, so-called because it was hoped a settlement could be reached in time to prevent the fall of the French Premier’s Administration. He told those present:

“If Signor Mussolini will co-operate with us in securing a settlement we will undertake at once to discuss finding a solution to the matters which are of primary concern to Signor Mussolini. We understand that he desires the solution of certain Mediterranean questions. If he will state which these are, France and Great Britain will at once do their best to meet those wishes.”

It was appeasement all over again.

Churchill vigorously opposed Halifax’s memorandum – it would be better if France quit the fight altogether than for us to be dragged down with them, and any suggestion that Britain should go cap in hand to the Italians and the tin-pot Mussolini for help would be greeted with scorn by people of every class and from every sphere of public life. In any case, he doubted that the Germans, poised as they were on the cusp of a great victor, would be prepared to listen to any proposal the terms of which might deprive them in any part of its full magnitude. He declared: “Even if we should be beaten, we should be no worse off than if we were to now abandon the struggle.”

Attlee, Greenwood, and Sinclair all spoke in Churchill’s defence indicating their approval of his stance, but Halifax reacted angrily: “The Prime Minister seems to suggest that under no conditions will we contemplate any course of action other than fighting to the finish.” He then made clear his own position: “I doubt I will be able to accept the view put forward by the Prime Minister.” The implication was clear - if the memorandum was rejected then his resignation would almost certainly follow.

Chamberlain, who had remained silent for much of the meeting, now weighed in on Halifax’s side – it was true that with Germany so close to victory any peace proposal would be unlikely to make much headway at this time, but a settlement would eventually have to be found and a lot can change in a week. All options should therefore be left on the table and as he believed negotiations were still possible the memorandum set forth by the Foreign Secretary was well worth pursuing.

His words too implied resignation and if that were to happen then the next would be his own. Churchill was losing the argument and under threat he backed away a little: “I will not join with France in asking for terms but if I find terms have been offered I will, of course, consider them.”

It was said with scant sincerity and Halifax suspected such, but he clung to the belief that reality would eventually overcome Churchill’s more fantastical visions of snatching victory from the jaws of defeat or of leading a last ditch defence of British liberties from the steps of 10 Downing Street.

The atmosphere had been tense, the exchanges heated, and voices raised to a level that belied the polite decorum of their surroundings. Churchill remained adamant that the fight must go on while Halifax was both bemused and dismayed by his failure to see that a settlement was the only means to avoid a military catastrophe and possible invasion.

The Inner Cabinet met again the following morning; a day that would see only 17,804 troops rescued from the beaches at Dunkirk. They would meet again that afternoon and tensions remained high as the argument raged back and forth, but still no agreement had been reached. Churchill made his position clear:

“Nations that go down fighting rise again, but those which surrender tamely are finished.”

Both Halifax and Chamberlain wearied of Churchill’s constant references to history, his appeals to past glories, and his emotional rhetoric. If only he would use his brain and think, let his head rule his heart for once. It failed to break the deadlock, and still a decision had not been made.

But Churchill’s forty years in politics had taught him a thing or two, if you cannot determine you can delay, where you cannot persuade in situ seek to do so elsewhere.

At 7 pm he adjourned the proceedings of the Inner War Cabinet to address a pre-arranged meeting of the Full Cabinet where he appealed directly to their sense of patriotism and in doing so taking their resolve for granted:

“I have thought carefully in these last days whether it was part of my duty to consider entering into negotiations with that man (Hitler). But it was idle to think, if we tried to make peace now, we should get better terms than if we fought it out. The Germans would demand our disarmament, our fleet, our naval bases, and much else. We should become a slave state, though a British Government which would be Hitler’s puppet would be set up – under Mosley or some such person. And where should we be at the end of all that? On the other side we have immense reserves and advantages.

I am convinced that every one of you would rise up and tear me down from my place if I were for one moment to contemplate parley or surrender. If this long Island story of ours is to end at last, let it end only when each one of us lies choking in his own blood upon the ground.”

His peroration complete spontaneous applause broke out, many rose to their feet and cheered others patted him on the back and some would later claim that the National Anthem was sung. Even Churchill, who had intended to manipulate their passions was astonished by the response. He would later write:

“There occurred a demonstration which considered the character of the gathering – 25 experienced politicians and Parliament men, who represented all the different points of view, whether right or wrong, before the war – surprised me. Quite a number seemed to jump up from the table and come running to my chair, shouting and patting me on the back. There is no doubt that had I at this juncture faltered at all in the leading of the nation I should have been hurled out of office. I was sure that every Minister was ready to be killed quite soon, and have all his family and possessions destroyed, rather than give in. In this they represented the House of Commons and almost all the people. It fell to me in those coming days and months to express their sentiments on suitable occasions. This I was able to do because they were mine also. There was a white glow, overpowering, sublime, which ran through our Island from end to end.”

Halifax and Chamberlain’s resistance had been broken. Even if they were to resign now, the impact could only be minimal. Churchill, doubting that Halifax could ever live down his reputation as an appeaser considered his political career over and in December 1940, he was replaced as Foreign Secretary by Anthony Eden. Soon after, he was sent to Washington as British Ambassador to the United States where his diplomatic skills could be best utilised while at the same time diminishing his influence at home.

Neville Chamberlain remained in the Cabinet until his death from cancer in October 1940.

On June 4 the evacuation from Dunkirk, which had begun with such low expectations, ended in triumph with some 375,000 troops rescued from its harbour and beaches including 228,000 men of the British Expeditionary Force, but this ‘Miracle of Deliverance’ could not conceal what had been a crushing defeat, and neither did Churchill try to do so.

On 4th June he addressed the House of Commons in a speech that would later be broadcast to the nation:

“We shall go on to the end. We shall fight in France, we shall fight on the seas and oceans, we shall fight with growing confidence and growing strength in the air, we shall defend our island, whatever the cost may be. We shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills; we shall never surrender, and if, which I do not for a moment believe, this island or a large part of it were subjugated and starving, then our Empire beyond the seas, armed and guarded by the British Fleet, would carry on the struggle, until, in God's good time, the New World, with all its power and might, steps forth to the rescue and the liberation of the old."

Britain would fight on, and she would do so alone.

Churchill had refused to be cowed by defeat, he had not given in to the demands of the Cassandra’s in his own Cabinet and within his inner-circle and had instead set his nation on a course of ‘blood, toil, tears and sweat’; but it was also one of great moral integrity that would result in the victory of good over evil and change the trajectory of world history forever.

Share this post: