D.C Stephenson and the Decline of the Klan

Posted on 2nd March 2021

The Ku Klux Klan, or Circle of Brothers, was originally formed as a fraternal society by ex-Confederate Army Officers in Pulaski, Tennessee, in December 1865. Its first leader was the legendary Cavalry Commander Nathan Bedford Forrest. Its membership remained small at first but started to grow as it began to be seen as a means to oppose Reconstruction and maintain white supremacy in the Southern States.

As the intimidation of blacks and their Republican supporters became increasingly widespread concerns in Washington grew until in 1871 President Ulysses S Grant felt compelled to act passing what became known as the Ku Klux Klan Act effectively proscribing its activities.

The clampdown and Bedford Forrest’s own criticism of the violence saw the Klan all but disappear by 1875, or at least go underground.

The intimidation of the black population continued however, becoming institutionalised in the Black Codes and the Jim Crow Laws as working through State Democratic Party Machines white supremacy was restored and maintained by the imposition of segregation throughout much of the South. It seemed there was no need for the Klan – but it wasn’t dead merely dormant.

In the wake of the economic downturn that followed the end of the Great War people were looking for alternatives and the most popular film of its day would provide it.

D.W Griffith’s Birth of a Nation released in 1916, which depicted the Ku Klux Klan as heroic figures defending good against evil caused a sensation, broke all box office records, and was even praised by President Woodrow Wilson following a private viewing in the White House.

The Klan itself had earlier been revived by the Alabama physician William Joseph Simmons in an elaborate cross burning ceremony on Stone Mountain in Georgia on 16 October 1915, and the convergence of post-war economic gloom, Birth of a Nation, and the now public profile of the previously Invisible Empire witnessed the popularity of the Klan soar with Klaverns not only in the South but throughout the mid-West, and even in the North. By 1925 its membership had reached six million and rising.

Indeed, affiliated to the southern dominated Democratic Party its influence was such it effectively had a veto over the 1924 Party Convention – a path to power appeared open. Yet within two years the Klan’s reputation lay in tatters, its credibility in free-fall, and its membership declining to a low from which it has never recovered.

One man was responsible for bringing the Ku Klux Klan to its knees, and he was – David Curtiss Stephenson.

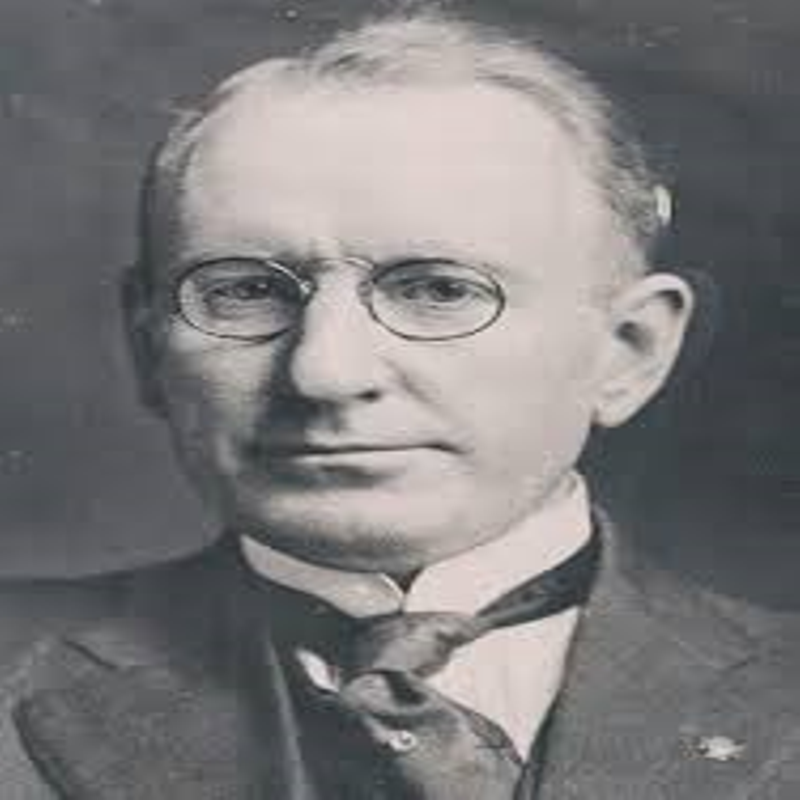

D.C Stephenson, known to his friends as Steve, was born in Houston, Texas on 21 August 1891, and though little is known of his childhood by the age of sixteen he had started work as an apprentice printer not long after joining the Socialist Party but it soon became clear that his interest in politics was personal not ideological for as soon as the Socialist Party’s fortunes began to wane, he left to join the Democrats.

In 1920, he moved to Evansville, Indiana, where he changed political allegiance once again and joined the Ku Klux Klan. He was to prove an excellent fund raiser and an able administrator quickly rising through the ranks to lead the Indiana Klan. He was a charismatic presence who willingly lied to burnish his own reputation and under his guidance Klan membership in Indiana rose to 250,000, or a third of the white male population of the State.

A fire and brimstone political preacher people would flock to hear him speak, even those who hated the Klan – he knew how to put on a show.

In November 1922, he backed Hiram J Evans in his leadership bid against the incumbent Grand Wizard William Simmonds. When Evans won, he rewarded Stephenson for his support by appointing him Grand Dragon for the other 22 Northern States. He was the perfect choice as he appeared to epitomise everything that was thought good about the Klan. He was a God-Fearing Christian, an avowed prohibitionist, a defender of the chastity of white protestant Womanhood, and he advocated a fair day’s pay for a fair day’s work. He even publicly disavowed violence, intimidation, and the burning of crosses. But it was all a lie and in private he was a drunkard and a lecher who would stop at nothing to get what he wanted.

The first thing he acquired was wealth to go with his power and he used his position as Grand Dragon to make money at every opportunity. He regularly took bribes, extorted money from vulnerable individuals, and ensured he was paid $4 out of every $10 of the initiation fee of every paying member, and $4 from every $6 paid for a Ku Klux Klan hood and robe.

In the 1924 Indiana elections he supported the Republican candidate Ed Jackson for Governor. He also lent his support to the Republican candidates of the other 22 States he controlled. Such was his power that many of these candidates were willing to put pen to paper agreeing to Klan control to win his favour. These he believed would be his security blanket, his political protection, should he ever need it. His political philosophy at this time can best be summed up in his own words: “Everything is fine in politics as long as you don’t get caught in bed with a live man or a dead woman.”

This was to be the high point of Klan influence and of Stephenson’s career. Not long after the empire he had so assiduously built primarily for his own benefit would come crashing down and he would be the cause of his own downfall.

At a party thrown by Governor Ed Jackson he met a 29-year-old schoolteacher Madge Oberholtzer, who ran an illiteracy programme in Indiana. She still lived at home with her parents which was not uncommon at the time for women of her age and had not seen much of the world. Indeed, it may well have been her naivety, and likely virginity, that first attracted Stephenson.

Though she enjoyed the attention and thought it would help her book programme to have such a powerful man as a friend she spurned his often-crude advances.

Stephenson was a man used to getting his own way however, and frustrated by Madge’s refusal to go out with him he decided to take what he wanted. He arranged to meet Madge at his home on the pretext that he wanted to discuss her book programme. Madge was loath to go but she couldn’t turn down the opportunity of perhaps receiving some much-needed funding.

Upon her arrival she was shocked to find Stephenson drinking and the worse for wear. She immediately made to leave but he had the door locked behind her. He then forced alcohol down her throat, drugged and kidnapped her.

On 15 March 1925, in a sleeping compartment on a train to Chicago D.C Stephenson repeatedly raped and abused Madge Oberholtzer. In doing so he bit her all over her body to the extent that a doctor who examined her later said that she looked as if she had been chewed by a cannibal.

Later that night, as Stephenson slept, the frightened and hurt Madge took his gun meaning either to shoot him or herself. Stephenson woke and managed to wrest the gun from her. He then proceeded to beat her severely.

While staying in the town of Hammond, Madge managed to slip away from Stephenson’s two accomplices Earl Gentry and Earl Klinck, long enough to enter a pharmacy and purchase some mercuric chloride tablets which she took in an attempt to commit suicide. Taken back to Stephenson’s hotel room she didn’t die but was left on the bed screaming in pain for days. Seeing that she was vomiting up blood, Stephenson eventually ordered his accomplices to take her back to Indiana. Before leaving she threatened him with the law, to which he replied, “I am the law in Indiana.”

Madge was taken back home by Gentry and Klinck and left to suffer alone in her bedroom. When Gentry was challenged and asked what had happened, hiding his face with his hat, he replied that she had been injured in a car accident. It was evident that this had been no car accident and her family sought urgent medical attention, but it was already too late, Madge was dying. But she was determined that Stephenson should face justice for what he had done to her.

Despite being in great pain she made a detailed and thorough death-bed confession before dying shortly after its completion on 15 April 1925, of liver failure brought on by mercury poisoning.

A death-bed confession was powerful testimony; D.C Stephenson, Earl Gentry, and Earl Klinck were all indicted on charges of kidnapping and second-degree murder.

Stephenson was unconcerned and remained confident of acquittal. After all, he was the most powerful man in Indiana, he was still popular, and he had an all-white male jury many of whom were or had previously been members of the Klan. He could also afford the best possible legal counsel and if required he still had the Governor in his pocket.

As the details of the case began to unfurl however, his support began to evaporate. He was described in Court as a drunk, a liar and a hypocrite. His behaviour in the Courtroom where he was regularly seen to be laughing and joking with his legal counsel and co-accused and talking through the testimony of witnesses just seemed to confirm people in the view that he was an unsympathetic and arrogant brute. With regards to the Klan, events outside of the Court House were also taking a turn for the worse.

The trial, which had acquired national notoriety had led to anti-Klan demonstrations and known Klansmen being attacked in the street. Following every new vile revelation mass Klan resignation followed. In Indiana Klan membership fell from 250,000 to below 4,000, while nationally it declined from a peak of nearly 10 million to just 120,000.

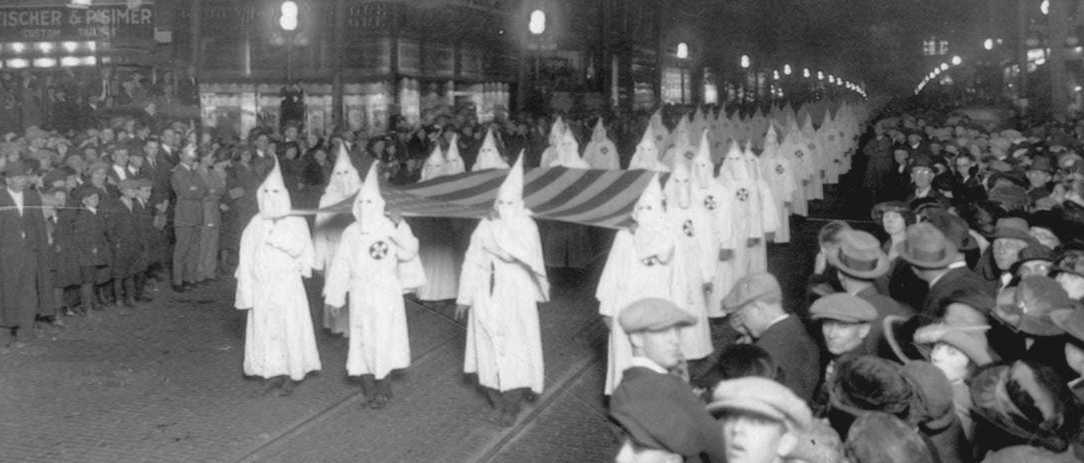

In a desperate attempt to staunch the haemorrhaging of support the Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan Hiram J Evans, disowned Stephenson and organised a mass-rally of the Klan down Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington – but it had come too late.

OOn 16 November 1925, David Curtiss Stephenson was convicted of Second-Degree Murder and sentenced to life imprisonment. His accomplices Earl Gentry and Earl Klinck were cleared of all charges.

Despite the conviction Stephenson remained confident that he would never go to prison. He expected Governor Ed Jackson to pardon him. After all, he had the documents that proved much of the State Legislature to be on the Klan payroll. Faced with the prospect of pardoning a much-despised murderer or being revealed and reviled as a corrupt politician, Governor Jackson chose the latter.

As he had threatened, he would Stephenson released the documents and a series of indictments followed not just in Indiana but throughout the Northern States he had controlled. But if doing so provided him with some satisfaction it did him little good and he was to serve 31 years in Michigan State Prison during which time at various parole board hearings he was to deny ever being a member of the Ku Klux Klan.

On 23 March 1950, he was released on licence but was to violate the terms of the licence and discovered hiding out in Minneapolis was sent back to prison to serve a further 6 years. He was finally released on 22 December 1956. In 1961, he was arrested for sexually assaulting a sixteen-year-old girl but the charges were later dropped for lack of evidence.

David Curtiss Stephenson died in Jonesboro, Tennessee, on 21 August 1966, aged 74, a little mourned and largely forgotten man except by those who had been his victims or had pinned their political ambitions to his amoral and corrupt coat tails.

Tagged as: Modern

Share this post: