Disraeli and Gladstone: Rivals for Power

Posted on 26th January 2021

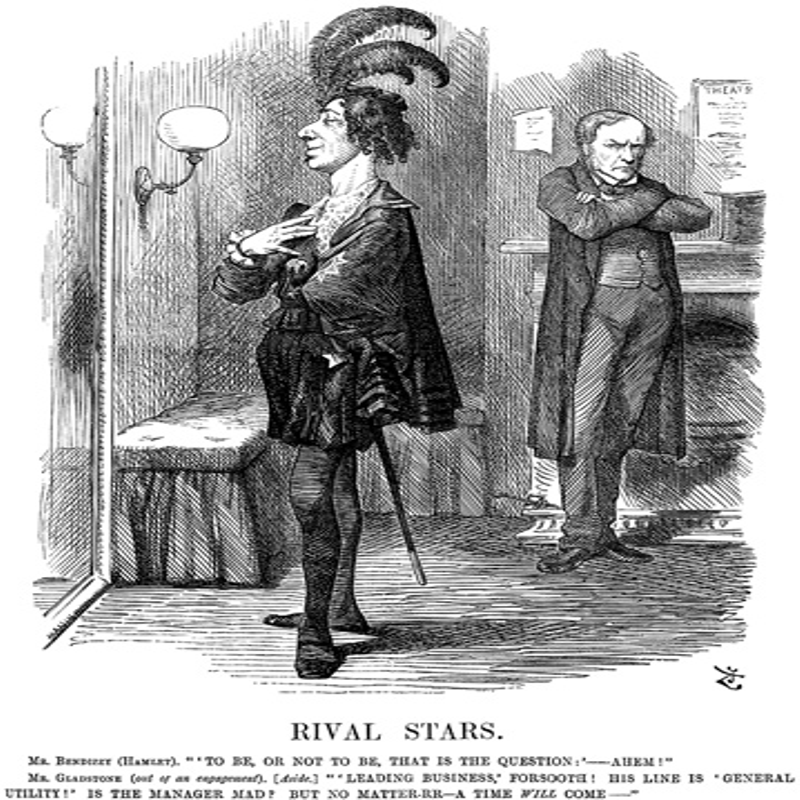

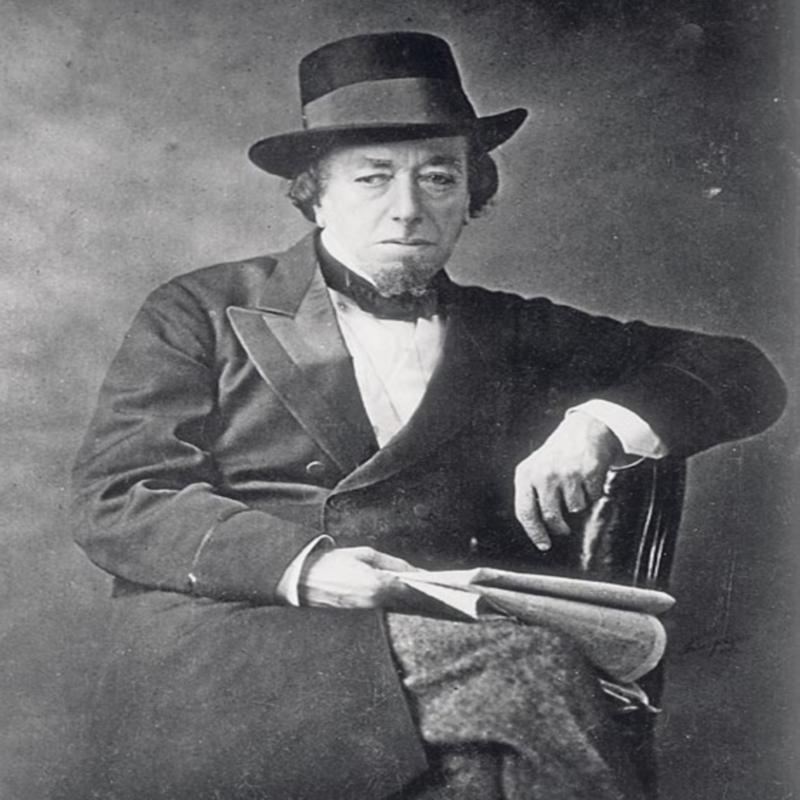

Neither man was of the aristocratic background from which Britain’s political elite were traditionally drawn while in character and personality they could not have been more different yet for more than forty years these two men were to bestride the Victorian political landscape like no other – they were the flamboyant Jewish convert to Christianity Benjamin Disraeli and the priggish protestant evangelical William Ewart Gladstone.

Benjamin Disraeli was born n 21 December 1804, the son Isaac D’Israeli a popular and successful author who as a member of the Bevis Marks Synagogue in London often found himself at loggerheads with the local Rabbis whom he considered an impediment to his own and his family’s future prospects and prosperity, and it was following yet another dispute and at the end of his tether that in 1817 he converted to Christianity.

Although he didn’t yet know it the young Benjamin’s baptism aged 12, had opened a career for him from which he would otherwise have been barred for no practising Jew could sit in the House of Commons. But his Jewish origins would cast a shadow over his political career, and he was to be the subject of virulent anti-Semitic abuse for the rest of his life often being portrayed in the satirical cartoons of the day as some kind of long-nosed, exotically dressed Eastern Potentate, egregious, fawning, and shifty. Indeed, it wasn’t unusual for him, certainly during his early years of campaigning to be greeted on the hustings by opponents holding up sticks topped with pork and shouting – here’s something for the Jew!

In public at least he took it in good heart but then he was proud of his Jewish roots and did nothing to conceal them, not that he was shy of romanticising his background and dressed accordingly cutting a quite extraordinary figure in his garish waistcoats, floppy felt hats, bejewelled fingers, and perfumed hair (an obsession of his) carefully combed into ringlets.

It was the physical manifestation of a character that still needed taming and it made him a difficult man to take seriously, a view that his early choice of career in both law and then finance would go some way to cementing with the former lacking the creative edge he required and the latter leaving him in debt for much of the rest of his life.

Seemingly not cut out for the humdrum of the workplace he turned his hand to writing becoming the author of what was known as ‘Silver Fork Fiction’ or tales of aristocratic life written for the entertainment of the aspiring middle-classes. His first novel Vivian Gray, though it sold and made him a little money was also the cause of much merriment and some ridicule for he did not mix in the highest social circles, and everyone knew it.

In fact, he cut an absurd figure with his tortured patois, foppish demeanour and exaggerated mannerisms conducting himself like some latter-day Beau Brummel. Others were even less flattering.

Even if his literary star waxed and waned it made him a living, but it also left him dissatisfied and unfulfilled. He looked elsewhere for inspiration, and it was to be the issue of Electoral Reform that brought the still ambitious but floundering Disraeli into politics, though it seemed at first with no greater chance of success than his previous choice of careers.

He was in favour of extending the franchise and stood as a Radical candidate for the constituency of High Wycombe in the General Election of 1832 and lost. He was to lose again three years later, and it seemed as if his attempts to enter the political fray were going nowhere.

At least since distancing himself from the gentle literary admonitions of popular fiction his reputation as an author of merit had improved and he was beginning to move in social circles that had previously been barred to him, and he was to prove a popular dinner guest, even if he lived in constant fear that his creditors would catch up with him and that his carefully constructed world would be brought crashing down by a court writ and a spell in debtors prison.

Despite his previous setbacks it was in politics that his ambitions now lay but unless he could find a supporter with influence and the requisite financial wherewithal to lend his candidacy some weight then it seemed that he would continue to be thwarted. Surprisingly perhaps given his reputation as a dilettante who was more show than substance, he found one, though in somewhat bizarre circumstances.

In 1834, he was introduced to Lord Lyndhurst, a leading Tory, and former Chancellor of the Exchequer by the lover they shared but rather than their mutual appreciation of Lady Sykes being the cause of petty jealousy the two men, both incorrigible gossips with a love for the finer things became firm friends.

Lord Lyndhurst took the aspiring politician under his wing bringing him to the notice of his colleagues and recommending him for membership of the influential Carlton Club. He also suggested that Disraeli should turn his considerable literary skills to writing letters and pamphlets on behalf of the Conservative Party.

After yet another unsuccessful attempt to win the seat of High Wycombe standing as a Radical, he disavowed his previous rejection of the old Tory Party as a relic of Britain’s past and embraced the Conservative cause without equivocation – the candidate of the Left had become a man of the Right.

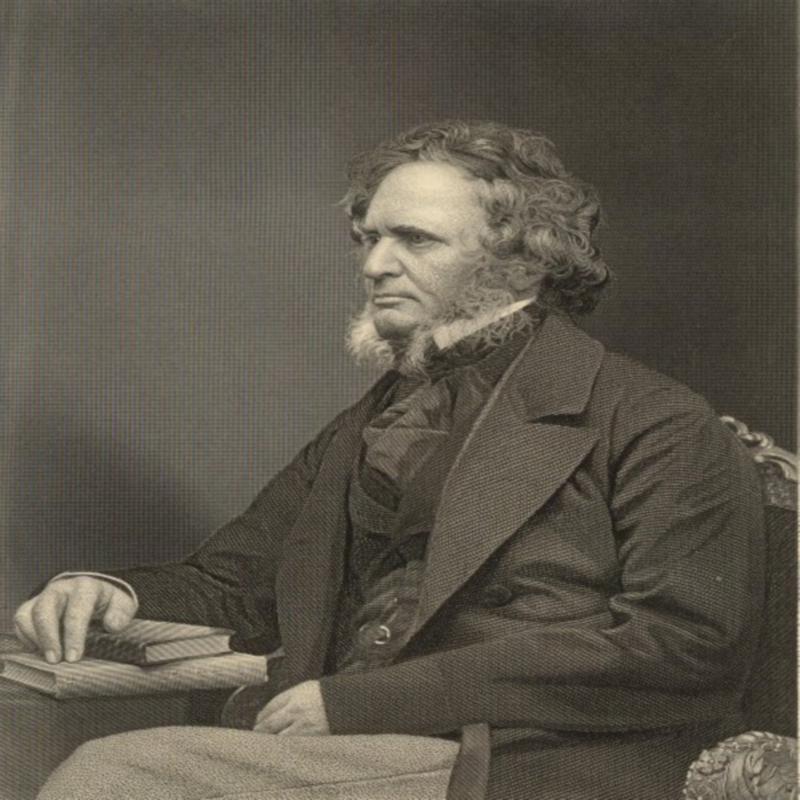

Whilst Benjamin Disraeli was climbing what he would later describe as the greasy pole William Gladstone, four years his junior, was making a name for himself in the hallowed halls of Oxford University, the educational establishment of choice for the scions of Britain’s ruling elite which though he was of more modest background fitted the supremely confident young Gladstone like a glove.

He had been born on 29 December 1809, into a prominent Liverpool merchant family which had made much of its wealth in the trans-Atlantic slave trade something that appeared not to trouble the morally self-aware young Gladstone at all. Indeed, commerce, trade, and the wealth accrued from it he found a great comfort though one may not have thought so by the manner of his dress and clumsy demeanour.

Sober, priggish, and deeply religious he was a young man old before his time with a sense of mission whose constant moralising and evangelical approach to life did not always sit well with his fellow students who on one occasion at least would break into his room and beat him up, and it wouldn’t be the last time he would be assaulted in such a manner.

On 16 May 1831, he addressed the Oxford Union in opposition to the extension of the franchise and for all his unpopularity as a bore the force of his convictions and the power of his oratory saw him end the debate to a standing ovation and an overwhelming victory.

Gladstone had greatly impressed those present one of whom was the son of Lord Newcastle who recommended him to his father who agreed to support the young Gladstone as candidate for the Rotten Borough of Newark and so in 1832, the same year as Benjamin Disraeli was being rejected by the voters of High Wycombe and at the age of just 22, William Ewart Gladstone was elected to Parliament.

The future leader of the Liberal Party began his political career as an orthodox High Anglican Tory and supporter of the status quo who opposed electoral reform, factory legislation and made in his maiden speech to the House of Commons a staunch defence of the slave trade working hard in Parliament to secure adequate compensation for his father who’d had to free the many slaves he still owned in the Caribbean following its abolition in 1834.

Whilst Gladstone was making a name for himself on the backbenches Disraeli was still struggling to get, himself elected. In April 1835, he was nominated the official Tory Party candidate in a by-election for the safe Whig Seat of Taunton - he lost again but had performed well on the hustings reducing substantially his opponents majority; his willingness to fight so hard in a losing cause at last earned him the respect he had previously lacked and in the General Election of August 1837 that followed the death of William IV and the accession to the throne of his niece Victoria he was at last elected the Member of Parliament for the Constituency of Maidstone. But there were harsh lessons still to be learned and his maiden speech in the House of Commons was nothing short of a disaster.

Dressed flamboyantly his affected mannerisms and grandiloquence of speech were greeted with so much laughter and howls of derision that barely able to make, himself heard he cut short his oration with the words: “I shall sit down now but you will hear me hereafter.”

Never again would he endure such humiliation, except that is at the hands of William Gladstone.

Benjamin Disraeli, much like his future rival, was under pressure to find a wife but always popular with the ladies the problem was not one of scarcity but preponderance – who of his many paramours would best suit his interests? In the end his choice would be a calculated, if unexpected one.

He eventually alighted upon Mary Anne Lewis (nee Evans) the daughter of a Naval Officer and widow of his recently deceased colleague, Wyndham Lewis.

His choice surprised many she being twelve years his senior and with a reputation for coquettish behaviour bordering on the silly. She was notorious for her non-sequiturs and if there was a foolish remark made at a dinner party, she was likely to have been the source of it. Even Disraeli’s own first impressions were less than flattering but they were to change, and he would later say: “I married her for money, but I would have married her for love.” She was in fact far less wealthy than he originally thought but their affection for one another was genuine enough and when he was with her it was said his troubles simply melted away. She was, he was fond of saying, more of a mistress than a wife.

Finding a woman willing to marry William Gladstone was to prove far more problematic for he lacked the charm of Disraeli and had few of the social graces; he didn’t do small talk, he was clumsy and unkempt, and had an intensity of conviction that left little room for romance - he simply wasn’t attractive to women. His amorous advances if they could be so-called were spurned time and again. Once when invited to dine with the daughter of a friend she was so repelled by his appearance as he walked up the driveway to the family home that she said aloud – I could never marry a man who carries his bag like that!

When he did eventually marry, to Catherine Glynne, the daughter of a Baronet, it was a surprise to everyone especially as only Gladstone could include a 140 word sentence in praise of the Almighty in his letter proposing marriage, but perhaps less so when one considers she was every bit as brilliant and eccentric as he though in a more attractive way – she was lively, engaging, absent minded, and untidy.

A union between the sociable Catherine and the curmudgeonly Gladstone did not seem a match made in heaven, but it was to endure 50 years and produce 8 children, though elements of dissatisfaction were to emerge in Gladstone’s behaviour.

He was also delighted to be able to move into Catherine’s ancestral home Hawarden Castle in Flintshire, Wales. Its environs were his solace, and it was a place he hated to leave.

Disraeli and Gladstone first met on 17 January 1835, at a dinner party arranged by Lord Lyndhurst to introduce his young prodigy to the Grandees of the Tory Party, and it was perhaps the beginning of their mutual antipathy for neither man merits a mention in their respective accounts of the night.

Politics in the 1840’s were dominated by the issue of the Corn Laws and the determination of the Conservative Prime Minister Sir Robert Peel to abolish them.

The Corn Laws had been introduced upon the conclusion of the Napoleonic Wars to restrict the importation of wheat from abroad thereby maintaining the profits of landowners at home but in doing so this kept the price of bread and other foodstuffs artificially high and was seen by many as an impediment to free trade, economic growth, and increased prosperity. Moreover, the ‘Hungry Forties’ as they became known were a time of great economic hardship which saw poor harvests, rising prices, increased unemployment, and the Workhouses full. There was also the looming disaster of famine in Ireland.

None of these issues could effectively be dealt with whilst restrictions on trade such as the Corn Laws remained in place. But the Conservative Party was in large part made up of the very landowners whose protection Sir Robert Peel now sought to strip away.

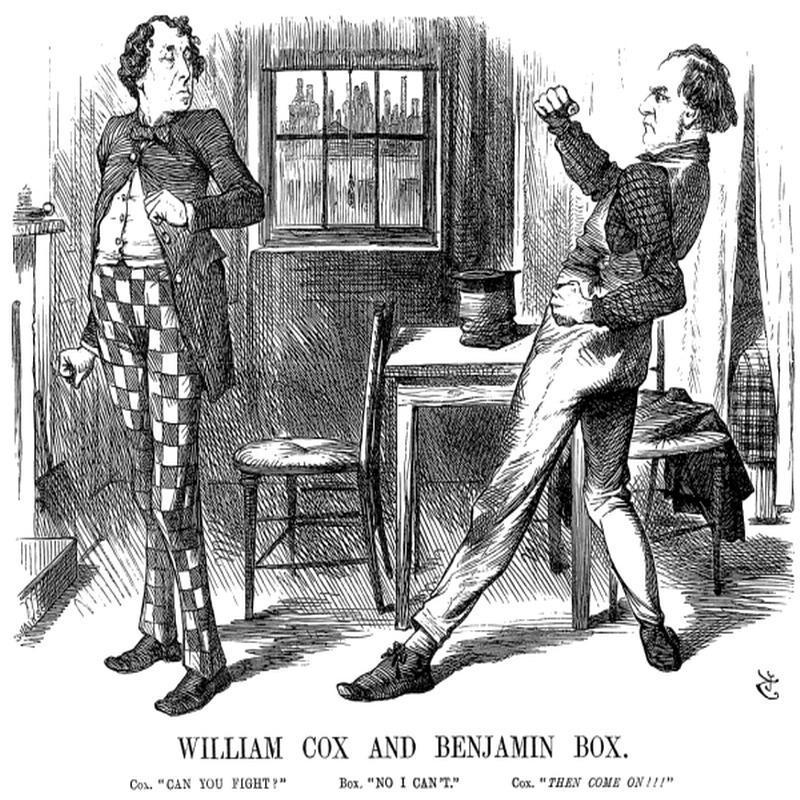

Disraeli, not a landowner himself, had barely expressed an opinion on the issue of the Corn Laws but spurred on by the sense of grievance he still felt at being overlooked by Peel for a place in his Cabinet he now seized the opportunity to lead the opposition to their repeal in Parliament. In a series of withering verbal assaults in the House of Commons Disraeli paid scant respect to the most prominent politician of his day and the leader of his own party, that he did so with wit and good humour only made the barbs more effective.

Peel, reduced to appealing for Whig support succeeded in repealing the Corn Laws in 1846 but Disraeli’s attacks upon him had so destroyed his authority that not long after he not only resigned as Prime Minister but left the Conservative Party altogether taking a third of its MPs with him, among them William Gladstone.

Gladstone, a long-time admirer of Peel never forgave Disraeli for what he perceived to be nothing short of self-aggrandising opportunism, and in this he had a point.

The ‘Peelites’, as they were known would never return to the Conservative fold despite repeated attempts at a reconciliation but instead under Gladstone’s influence coalesced with the Whigs and the Radicals to form the Liberal Party.

The rancour between the Conservative Party and the Peelites was such that it allowed the Whigs to form a minority Administration that would see them excluded from power for the next five years.

Disraeli used his time in opposition to good effect utilising all his political skills and powers of persuasion to rise rapidly through Conservative Party ranks becoming the leader of the party in the House of Commons, a position of prominence that made him a difficult man to overlook. This was no mean feat given the proclivity of his enemies to beat him with the proverbial stick of his Jewish origins and all the perceived negative traits this entailed – money grubbing, casuistry, deceit, and louche behaviour. Disraeli took all such abuse on the chin not that his forbearance in such matters indicated a forgiving nature for he understood well-enough the brutality of politics and would respond accordingly when required. He would say: “There is no act of treachery or meanness of which a political party is not capable; for in politics there is no honour.”

Gladstone, by contrast, though political to his fingertips would from time-to-time display an unwillingness to engage and opposition bored him. He decided to indulge other pursuits, his ‘calling’ to improve the morals of mankind and to do God’s Work.

In 1848, he founded the Church Penitentiary Association for the Reclamation of Fallen Women, an abiding interest of his. Money was raised to support establishments that would provide for a fallen woman’s education and imbue them with the moral discipline that would save them from the path of sin but Gladstone himself preferred a more hands on approach.

In May 1849, he began his ‘rescue work’ as he liked to call it visiting those areas of London where prostitutes were known to ply their trade always with an eye for the prettier among them.

Those fallen women he encountered would be invited to accompany him home and avail themselves to a little moral persuasion before being released back onto the streets with food for thought while Gladstone dutifully noted in his journal, often in Italian should someone accidentally stumble across its contents, the events of the night. Sometimes the entry would be decorated with the small drawing of a whip perhaps indicating a predilection or the need for self-chastisement, or perhaps neither.

While he may have harboured private doubts as to the propriety of his actions in public he did not.

When in May 1853, an unemployed man who went by the name of Wilson recognised Gladstone approaching prostitutes in Panton Street near Piccadilly Circus he threatened to reveal his behaviour to the press unless he provided him with money, or at least a job.

Gladstone did not hesitate to summon a policeman and have Wilson arrested and charged with blackmail.

A leading politician importuning prostitutes in the dead of night would today herald the end of a glittering career, but a Victorian man of substance was given the benefit of the doubt and Wilson was found guilty and sentenced to a year in prison. Perhaps out of a sense of guilt Gladstone would later get this sentence reduced.

When he wasn’t saving fallen women and labouring for the betterment of mankind Gladstone liked nothing more than to return to Hawarden Castle and spend time with his family (he was to have 8 children by Catherine while Disraeli and his wife Mary were to remain childless) and indulge his passion for self-improvement translating Homer and other ancient texts for reasons of intellectual discipline before rolling up his sleeves and chopping down trees, the physical manifestation of a muscular Christianity.

Disraeli, who had neither the energy of his great rival nor any burning desire to inculcate the religious ethos and improve the morals of mankind, did not allow work to impinge upon what were in any case brief enough moments of relaxation. When he disengaged from the intrigues of Westminster to return to Hughenden Manor (the house he had purchased with loans of over a million pounds from Conservative allies, a level of indebtedness he was willing to undertake to secure the lifestyle he believed a prominent member of the party should be accustomed to, that of a country gentleman) it was to gaze upon the morning sun as it cast its light upon his gilded life away from politics, to read and drink champagne, to walk in the grounds with his darling wife, and plant flowers in the garden, the primrose being a particular favourite.

In June 1852, the Whig Government of Lord John Russell fell and in the subsequent General Election the Conservatives were unable to secure a majority but as the leader of the largest party the Earl of Derby was nonetheless asked to form an Administration. Its prospects of survival were slim reliant as it was upon the support of the Peelites, now led by Lord Aberdeen since the death of Sir Robert Peel in 1850.

Given that this was the case Derby’s choice of Disraeli to be his Chancellor of the Exchequer seemed to fly in the face of reason for though he was the rising star of the party, its most capable parliamentarian, and an outstanding orator, within the ranks of disgruntled Peelites he was little short of a hate figure. Yet it was he who was now tasked with devising a budget that would unite all factions behind the new Government.

Disraeli was no economist and was to spend many a sleepless night nervously pondering the likely reception to a budget the details of which were a mystery even to him but his appointment to one of the leading Ministerial posts in the land and the likely financial rewards it would bring him personally had simply been too great to decline. Lord Derby’s assertion that he need not worry the figures would be provided for him he found less than reassuring and his fear that he was about to make a fool of himself remained a very real one.

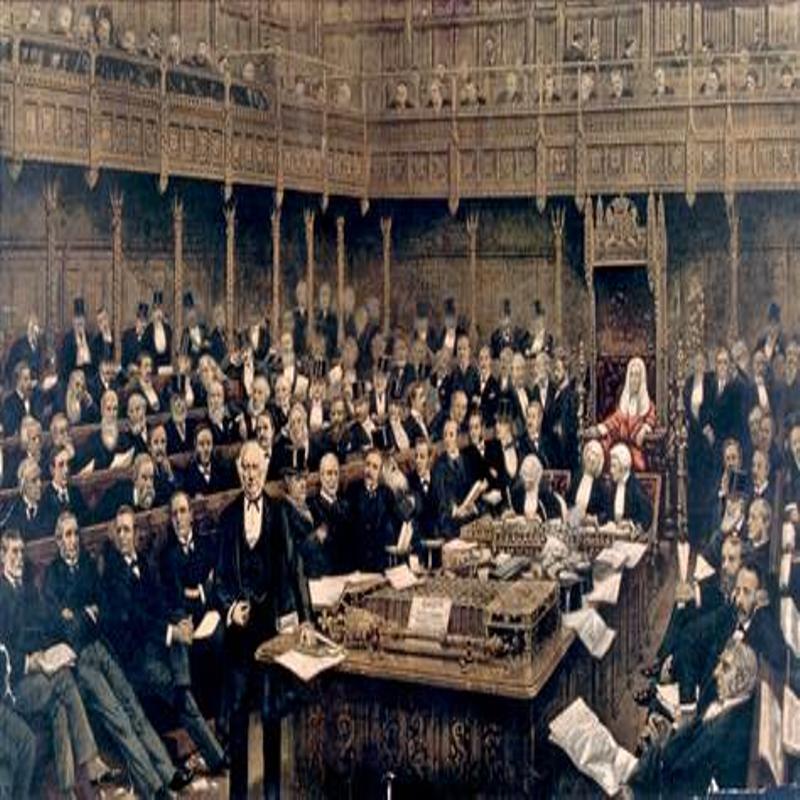

But his powers of erudition had not deserted him and delivering his budget speech on 3 December 1852 before a packed House of Commons as a storm raged outside which howled with nascent fury and made the windowpanes shudder, he held his audience in the palm of his hand mocking his opponents with caustic wit and no little charm before recommending his budget to the House and sitting down to thunderous applause.

Yet all the brilliance of his oratory could not disguise the failings of the budget itself and his evident delight at its reception was to be short-lived as an earnest and somewhat animated William Gladstone pushed himself to the fore to respond.

In a carefully calculated address, he proceeded to forensically pick apart and demolish Disraeli’s budget proposals revealing as he did so, to his mind at least, the Chancellor to be the fraud and charlatan he undoubtedly thought he was.

Forced to remain mute as a result of his own inadequacies he was unable to respond to Gladstone’s withering assault able only to think this man was unhinged and not a gentleman. When it came to the vote his budget was rejected by 16 votes on the Floor of the House. Well might he remark: “My idea of an agreeable person is a person who agrees with me.”

Just over three weeks later following the fall of the Conservative Government, William Gladstone replaced Disraeli as Chancellor.

It was a tradition that the departing Chancellor would be compensated by his successor for the cost of furniture at the Treasury. Despite his own always precarious financial circumstances Disraeli paid his predecessor as expected but Gladstone refused to heed precedent and when the departing Chancellor complained he was told to take up the issue with the Office of Public Works. It seemed Disraeli was right - the new Chancellor was no gentleman at all.

In response Disraeli refused to hand over the ceremonial robe of the Chancellor of the Exchequer thereby denying Gladstone the insignia of his rank. Politics had just got personal. The robe remains at Hughenden Manor to this day.

Gladstone considered, himself a man of probity and sound finance, and so it would prove to be. His terms as Chancellor, in marked contrast to his immediate predecessor contained few rhetorical flourishes metaphorical or otherwise; there would be no needless taxes nor money provided for vanity projects and reckless overseas adventures. He was not a tax-and-spend Chancellor, instead good management would prove the foundation of sound finance and his budgets intended to cover the expenses of Government and little else would be a business model for the Treasury that is still followed to this day.

Gladstone was to be Chancellor of the Exchequer for ten of the next fourteen years and his budget day address would become one of the great set-piece events of the parliamentary calendar for though they might be long, detailed, and exacting they were never dull.

He neither liked taxation nor the imposition of duties and tariffs but he disliked borrowing even more, nonetheless he would reduce all three year on year. If he had to raise taxes, they would fall upon those able to pay and his reduction in the number of duties would see cheaper food on the table. Also, his determination to abolish duties on paper which restricted the poor’s access to information, the so-called tax on knowledge, was to facilitate the emergence of the radical and popular press. Such budget enactments earned him the reputation, not entirely merited, as the ‘Peoples William.’

Gladstone then, was thought a radical, and as a radical he would surely support the extension of the franchise. In fact, he hadn’t supported it in 1832 and he still didn’t favour it well into the 1860’s but this was to change as he rode the wave of popular acclaim.

Whilst Gladstone was establishing his reputation as the outstanding Chancellor of his and future generations, Disraeli was becoming an increasingly effective and powerful, if not always popular, Leader of the Conservative Party in the House of Commons opposing the rarely less than belligerent and bellicose Administration of Lord Palmerston.

In February 1858, the Conservatives were briefly returned to power and Disraeli having learned the lesson that it is sometimes wise to do no more than required returned to the Treasury a much-chastened man. Despite his desire to be considered a great Chancellor of the Exchequer he never had as firmer grip on the finances and fiscal mechanics of the job as Gladstone, and he knew it.

The Earl of Derby’s Second Administration lasted less than eighteen months but it was enough time for Disraeli to force through rules that would allow the House of Commons to determine what denominational oath an elected Member would be permitted to take making it possible for those not of the Christian faith to take their seat in the Chamber. Not long after, much to Disraeli’s satisfaction, Lionel de Rothschild became Britain’s first practising Jewish Member of Parliament.

Despite his now prominent role within the Liberal Government Gladstone remained a Peelite but many still considered him to be a High Tory Anglican at heart and as leader of the Tories in the House, Disraeli was under pressure to lure him back into the party. Consequently, he wrote to his arch-enemy pleading with him to put personal animosity aside and re-join the ranks. His attempt to heal the rift was given short shrift by Gladstone who replied indicating that the rift was far deeper than he could ever imagine or know.

It wasn’t long before the Liberal Party was returned to power, and such was Palmerston’s popularity in the country that the Earl of Derby was disinclined to oppose him in Parliament believing that to do so was detrimental to the Conservative Party’s prospects.

Disraeli disagreed but when in the General Election of July 1865, the Liberals were returned with an even greater majority Derby’s fears that the Conservatives would never again form a majority Government appeared to be borne out and they were plunged into a mood little short of despair.

Relief came when on 18 October the seemingly robust 80-year-old Palmerston died suddenly to be replaced by the similarly aged Lord John Russell.

A vacancy would soon arise at the top of the Liberal Party and Gladstone was a leader-in-waiting – the ‘Peoples William’ now took to the road.

He’d had a political conversion (a mere change of the heart or opinion was never good enough for Gladstone) and he now embraced the issue of electoral reform with a gusto that only he could muster. He toured the towns and cities of the industrial north to address rallies attended by thousands of people in support of his proposals for the extension of the franchise.

But Gladstone’s Reform Bill put before Parliament on 12 March 1866 to give the vote to working men who met the required minimum property qualification was met with fierce resistance both by the Conservative opposition and elements within his own party both for reasons of going too far and for being too modest.

Disraeli, who needed no encouragement to resist any proposal made by William Gladstone, brilliantly rallied the opposition ensuring not only the defeat of the Reform Bill but the fall of the Liberal Government as a result.

On 22 June 1866, the Conservatives formed yet another minority Administration, but the death of Palmerston had provided them with the opportunity to revive their fortunes and Disraeli was determined to seize it. When rumours reached Gladstone from sources close to the Prime Minister that Disraeli had plans for an Electoral Reform Bill of his own he dismissed them as mere poppycock and palpably absurd. But the rumours were true.

Disraeli was aware of the need for Electoral Reform especially in the still rapidly expanding urban boroughs which remained largely disenfranchised but he was also responding to the fear expressed by the Earl of Derby that the Conservative Party’s future as an electoral force was under threat. He believed that by giving the working class the vote he would guarantee their loyalty in future elections and that if the people were to become more involved in the democratic process then it should be the Conservatives who were responsible for it and it should be the Conservatives who benefited from it.

But many within his own party who believed any extension of the franchise to be an unnecessary and dangerous development and had rallied to Disraeli’s support in his opposition to Gladstone were shocked at what they now saw as a betrayal.

Disraeli dismissed their concerns, but he would be reliant upon Liberal votes to secure the passage of the bill and as a result was forced to accept amendment after amendment making his Reform Bill even more radical than he had originally intended, though he refused to countenance any change proposed by Gladstone.

Passed in August 1867, the Disraeli’s Electoral Reform Bill gave the vote to 938,427 working men increasing the electoral roll by 88%, though some householders, most agricultural labourers, and of course women were still excluded.

Still only 2 in 7 adults were eligible to vote but Disraeli had made Britain a democracy of the people and not just of the privileged few.

Discord within the Conservative Party caused during the debate over the Reform Act eased as Disraeli received widespread acclaim in the press and across the political spectrum for his determination and vision, though not from Gladstone who had seen his own plans gazumped in what he believed an act of outrageous and self-aggrandising chutzpah typical of the man.

Disraeli had taken responsibility for the passage of the Reform Act not only because it was his policy, but as a result of the Earl of Derby having to operate from the House of Lords and also because of the gout that often saw him absent from proceedings. Indeed, his ill-health was to become so severe that by early 1868 he was effectively housebound and increasingly incapable of discharging his duties as Prime Minister.

In February, he wrote to the Queen to resign as Prime Minister recommending that Benjamin Disraeli replace him. A delighted Queen wrote to her eldest daughter in Germany: “Mr Disraeli Prime Minister! A proud thing for a man risen from the people to obtain.”

William Gladstone thought otherwise and dwelt instead upon exactly what magic elixir he had concocted to obtain first the Chancellorship and then the Premiership ahead of him? He returned to Hawarden to chop down trees.

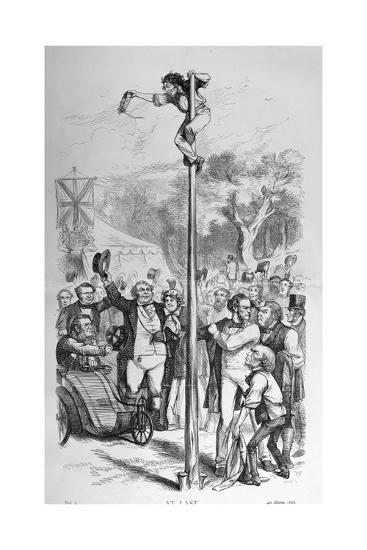

As the letters and telegrams of congratulations flooded in a clearly delighted Benjamin Disraeli was often heard to repeat the remark, he had made to the Queen following his appointment – I have climbed the Greasy Pole.

Disraeli’s rise to the top of the Greasy Pole as he put it may have been a great personal triumph, but his first Administration was to be a short one.

The passage of the 1867 Reform Act had triggered a General Election for December of the following year which despite his promises to the contrary the Conservatives lost, for in forcing through the Act he had neglected to supervise the redistribution of seats that would see those votes transformed into election victory and the rush to update the electoral roll to reflect the new franchise actually worked against him with many voting for a Liberal Party which more closely resembled the radical policies they espoused.

It seemed that Disraeli’s promise of a political bounty for the Conservatives from the extension of the franchise had proved a hollow one, but he was in fact to be proved correct over time for despite the emergence of the Labour Party more than a third of working-class voters have regularly cast their ballots in favour of the Conservative Party ever since.

In the brief ten months of his Premiership Disraeli did however pass some important legislation: he ended the spectacle of public execution following the rancour caused by the hanging of the Fenian terrorist Michael Barrett for the Clerkenwell Bombing that had left 12 dead, and he passed the Corrupt Practices Act cleaning up the Augean Stables of electoral malfeasance and the financial gravy train that accompanied it.

But Disraeli’s reward for making Britain something akin to a participatory democracy was to be defeated at the polls by a margin that was a firm rejection of the party he led as the Liberals, now under the leadership of his great rival William Gladstone, were swept to victory with a 116-seat majority.

The Liberal politician Evelyn Ashley was with Gladstone at Hawarden Castle when he received the news that he had been summoned to the Palace to be asked to form a new Government. He famously described the scene:

“In the park at Hawarden, I was standing by Mr Gladstone holding his coat on my arm while he, in his shirt sleeves, was wielding an axe to cut down a tree. Up came a telegraph messenger. He took the telegram, opened it and read it, then handed it to me, speaking only two words, namely, ‘Very Significant’, and at once resumed his work. After a few moments the blows ceased and Mr Gladstone, resting on the handle of his axe, looked up, and with a deep earnestness in his voice, and great intensity in his face, exclaimed: ‘My mission is to pacify Ireland.’ He then resumed his task, and never said another word until the tree was down.”

Ireland would be the albatross that hung around his neck.

During his many years as one of the most prominent politicians in the land Disraeli had formed a good relationship with Queen Victoria who charmed in his presence, as indeed many were, welcomed his visits. He reminded her of her beloved Lord Melbourne who had been Prime Minister on her accession to the throne, though the similarity may have been one more of affection than shared characteristics.

As a former Prime Minister, it was only right and proper that Disraeli should be in possession of a Title. He certainly thought so, and the Queen agreed but in accepting a Title Disraeli would have to lead the opposition from the House of Lords and not the House of Commons. As such, he persuaded Victoria to ennoble his wife Mary Anne as Lady Beaconsfield while he remained a commoner but a Lord-in-waiting inheriting the Title should his wife pre-decease him or he retired from politics.

Sadly, for Disraeli it would be the former when on 15 December 1872, Mary Anne died, aged 81, after a long illness during which advised to turn her thoughts towards God, she responded that she could think only of Benjamin – he was her Saviour.

A marriage of convenience had evolved into strong ties of love and mutual affection as the flirtatious Mary Anne and the romantic Benjamin found themselves the perfect match - he the lovelorn hero of his own novels, she more of a mistress than a wife – they were a devoted couple.

Disraeli was distraught at her death and even Gladstone, who had a great fondness for Mary Anne, if not her husband, felt compelled to pen a letter of condolence.

But there is little room in politics for sentiment and upon inheriting the Title of Lord Beaconsfield the popular press soon dubbed him Lord Baconsfield should he need reminding, however popular he might become, of his Jewish origins.

The cornerstone of any Gladstone Administration was financial rectitude, the requirement to maintain taxation at levels that facilitated consumer spending whilst at the same time encouraging thrift. His foreign policy was to seek peace, promote cooperation in international affairs and to guarantee the regular and unhindered flow of free trade. Empire building, he believed was for visionaries and dreamers who tore at the purse strings but did no accounting. It did not make for exciting Government.

But the achievements of his first Administration were significant and profound nonetheless, especially with regard to the nation’s institutions.

The administration of the Poor Law he placed under Local Government supervision to ensure that charity and alms were distributed according to need not sentiment and that the Victorian demand for self-improvement in both personal morals and the work ethic be paramount in the consideration of poor relief; in the Army he ended the custom of being able to simply purchase a commission establishing a trained professional Officer Corps where promotion was gained on merit not means; access to the Civil Service would in future be via examination and not just a tool of familial largesse; and the Universities he opened up to Catholics and non-Conformists who could now study and graduate on equal terms with their Anglican fellow students.

Other reforms followed including in the justice system and the 1871 (Forster) Education Act which provided elementary schooling for all children aged between 5 and 13; in 1872 he introduced the Secret Ballot which allowed people to vote for the first time free of threat and intimidation; and he also passed his first Irish Land Act intended to improve landlord–tenant relations. It didn’t, and he was soon to discover that ‘pacifying Ireland’ as he called it was easier said than done.

Gladstone was nothing if not a busy man believing as he did that to govern just for the sake of it, to merely maintain the status quo and not improve where improvement was required was a betrayal of the people’s trust. Not all agreed, and many found his reform agenda forced upon them in that objectionable finger jabbing way of his unnecessary interference in established ways that had worked well in the past.

In truth, his First Administration was never popular, the politics were made for a dull palette and his moral tone and hectoring style made him a great many enemies but then he was used to making enemies even among friends. Yet he was effective, and just as Benjamin Disraeli could be said to have set Britain on the path to becoming a fully participatory democracy so William Gladstone created the first stirrings of a meritocracy where advancement would be based on talent and not privilege and nepotism.

Given Gladstone’s majority in Parliament Disraeli was not over-exercised in opposing his always full legislative programme, indeed he may have agreed with much of it, but then his objection to Gladstone was always as much personal as it was political, not that the two things were divisible.

Disraeli instead concentrated his efforts on strengthening his own position within the Conservative Party instead and transforming it into the most formidable election winning machine in British political history.

Sensing his government was running out of steam in January 1874, Gladstone seeking a fresh mandate from the people called a snap General Election. His Liberal Party was ill-prepared however, and perhaps aware of this Gladstone called for the ballot to take place just three weeks after Parliament was dissolved, a campaign considerably shorter than the usual three months.

Disraeli and his Conservatives on the contrary were very well prepared. He had reorganised his party just for this moment and had spent many of the last few months allowing Gladstone to stew in his own unpopularity whilst he toured the country addressing meetings and receiving a rapturous reception.

The 1874 General Election was a triumph of Conservative Party organisation for despite polling 8% fewer votes they won 116 more seats with dozens of constituencies being uncontested by the Liberals at all. Indeed, such was the shambolic nature of the Liberal Party campaign the MP George Howell wrote to Gladstone to complain: “We have lost not by a change of sentiment so much as by want of organised power.”

Gladstone did not take the defeat well and he certainly wasn’t prepared to accept the blame for it. He was a man who led a devotional life, at home, at the pulpit, and in public service and so to lose to a shallow fraud like Benjamin Disraeli was quite bad enough.

Disinterested in leading the Opposition from the backbenches Gladstone did what he would often do and retired from active political life returning to Hawarden Castle to chop down trees and write pamphlets.

Disraeli could barely contain his satisfaction; he had often said he did not mind that Gladstone would have a card up his sleeve but he did resent the fact he believed God had put it there – well on this occasion both Gladstone and God had been trumped.

Queen Victoria was certainly delighted that the charming Benjamin was back, she had long ago tired of being addressed by Gladstone as if she were a public meeting.

Although Disraeli never had the raw energy of Gladstone and certainly did not share his love of hard physical labour, his government was to be no less busy, and in unexpected areas as a raft of domestic policies transformed class and labour relations:

The Conspiracy, and Protection of Property Act decriminalised trade union activity on the part of the individual; the Employer and Workers Act permitted workers to sue their employers for breach of contract; the Artisans and Labourers Dwellings Improvement Act provided loans to Local Authorities to clear slum dwellings and build workers homes.

Little wonder that the Liberal MP Alexander MacDonald might remark – the Conservative Party has done more for the working class in five years than the Liberals have done in fifty..

The Public Health Act of 1875 which provided for pavements and street lighting in towns, the need for a Sanitary Inspector and Medical Officer to be appointed to every Health Authority, the application of stronger regulation regarding clean water and unadulterated food, and the requirement that every new house built had be fully plumbed did much to improve the hygiene and health of the people. But it was in foreign affairs that Disraeli would be seen to excel.

Disraeli’s relationship with Queen Victoria was often the cause of derision for to say it was unapologetically fawning would be an understatement and he wasn’t shy in admitting as such: “Everyone likes flattery and when you come to Royalty, you should lay it on with a trowel.”

At their formal meetings he would fall upon one knee and kiss her hand. It was subservient and theatrical, but it was not insincere for he truly believed that the Monarchy was the foundation upon which all else existed and he feared its dissolution and what might follow as a result. The preservation of the Monarchy was never far from his thoughts, and with good reason.

At the time of the Princess Alexandrina Victoria’s accession to the throne in June 1837, the Hanoverian Monarchy had fallen into disrepute and was held in such low regard that it had become the stock-in-trade of satirists and a regular subject for the poison pen lampoons of the popular press. At least the young Victoria would represent a breath of fresh air following decades of drunkenness, debauchery, extra-marital affairs, and illegitimate children. And so, it would prove. Her marriage to Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg Gotha, a sober and hard-working man, would go a long way to restoring the reputation of the Monarchy.

They were a devoted couple who disregarded the trappings of Royalty and its grander manifestations for a more modest approach living when possible, at their residence, Osborne House, on the Isle of Wight where they portrayed themselves as the model loving Victorian middle-class family. All this changed however, when on 14 December 1861, Prince Albert died following a short illness. Victoria was plunged into deep mourning and was to withdraw from public life for the next decade. This greatly concerned Disraeli who saw an absent Queen as grist-to-the-mill for an increasingly vocal Republican Movement which could argue with some justification what was the point of having an expensive Monarchy that said nothing, did nothing, and was seen by no one? Disraeli would be a prime mover in persuading Victoria to engage once more with her subjects and he played a significant role in re-fashioning the Monarchy during her reign just as he had earlier re-modelled the Conservative Party.

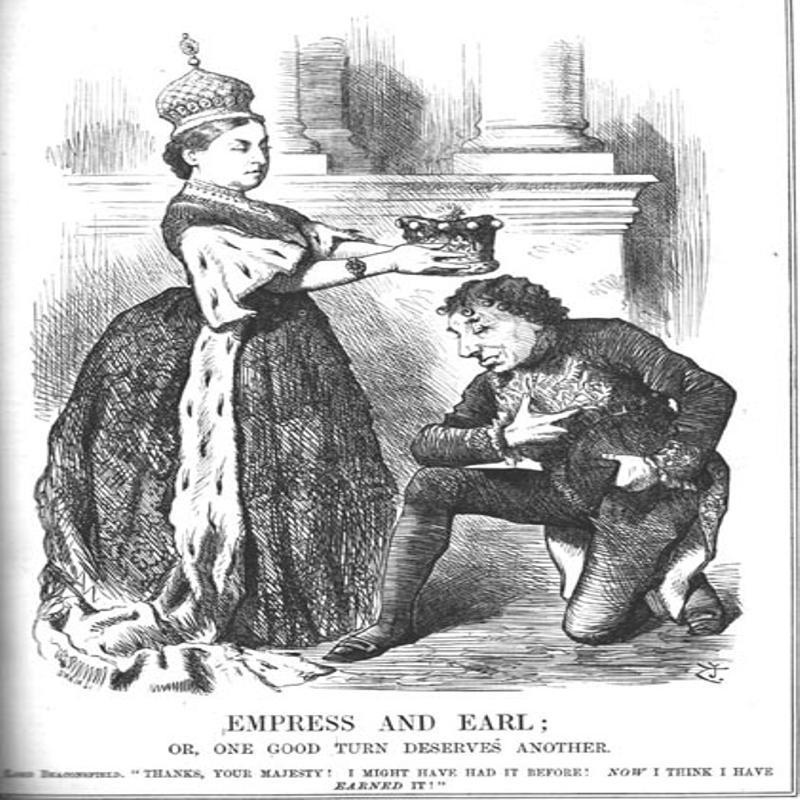

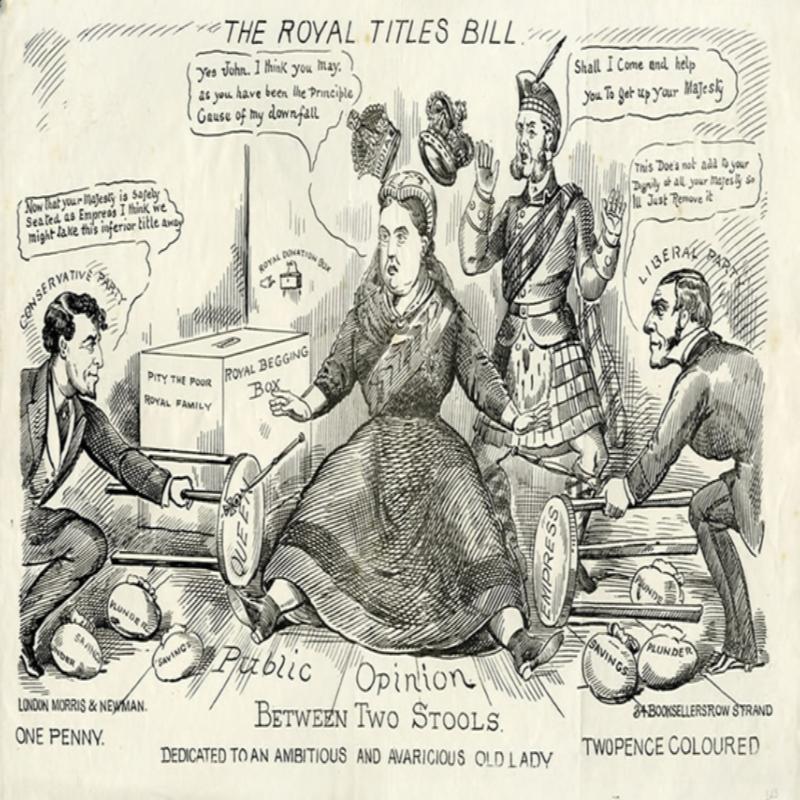

His devotion to the Queen reached its apotheosis with the Royal Titles Act of 1876.

Victoria had long felt that her status as a ruling Monarch at the head of an Empire should be formally recognised and her Title be elevated to that of Empress. Disraeli had no personal objection to this, but he knew that it was politically contentious seen by many in a country where the primacy of Parliament was paramount as an unnecessary and intolerable assertion of Royal power and the rumour that the Queen had herself agitated for it only seemed to confirm this.

He was aware that forcing through the Royal Titles Act that would make Victoria, Empress of India would make him more enemies that friends but he persisted nonetheless and though when it came to the vote it was passed with a comfortable majority it had taken all Disraeli’s powers of persuasion to ensure its safe passage. The new Empress at least, was delighted, as also were the jingo press – good old Dizzy!

William Gladstone’s attitude towards the Monarchy, however, was very different.

By no means a Republican he nonetheless tolerated rather than welcomed the Queen’s constitutional role in the political life of Britain, and though he would behave with due deference his manner would be perfunctory and matter of fact; charm was not after all an inherent characteristic and it was a weapon he would not have used even if he could, he preferred the power of argument. Victoria dreaded her meetings with Gladstone, as upright and distant he would lecture her at length on whatever issue of the day had engaged him and the fact that she found such a serious man so objectionable when for so many years she had been married to one is a testament of his ability to offend.

But politics is rarely dull regardless of Gladstone’s best efforts to make it so.

On 17 November 1869, the Suez Canal was formally opened.

The idea of the French diplomat Ferdinand de Lesseps it ran 120 miles across the Isthmus that separated the Mediterranean from the Red Sea and reduced the sea journey from Europe to East Asia by some 5,000 miles and many weeks of perilous sailing around the Continent of Africa and past the Cape of Good Hope. Its construction had been accompanied by the rather grand statement that it was to be used in time of war as in time of peace by every vessel of commerce or war without distinction of flag. Not all agreed.

Britain had opposed its construction from the outset and had done its utmost to impede its progress it being felt that it was not in the Empires interests to facilitate easier access to the Orient for European shipping which could only pose a threat to her Far East possessions and virtual monopoly on trade. There were also concerns that it could fall into the hands of a hostile power. But its strategic significance was not immediately seized upon by those who might have been expected to do so and de Lesseps struggled to sell shares in his artificial waterway providing Disraeli with the opportunity to manipulate the situation to his advantage - Britain may have been unable to prevent its construction but it could at least determine how it was used and by whom.

The lack of enthusiasm for the project made many who had already invested begin to doubt its financial viability and there was little disinclination on their part to divest themselves of their interest. Disraeli was eager to seize the opportunity but aware that Gladstone had previously declined the offer to invest and fearing opposition in Parliament he by-passed the Treasury and instead secured a loan from his friend Lionel de Rothschild. Upon learning that the Egyptian Khedive was looking to sell his shares Disraeli did not hesitate to act and on 25 November 1875, he signed the contract of purchase for a fee of 100,000,000 francs.

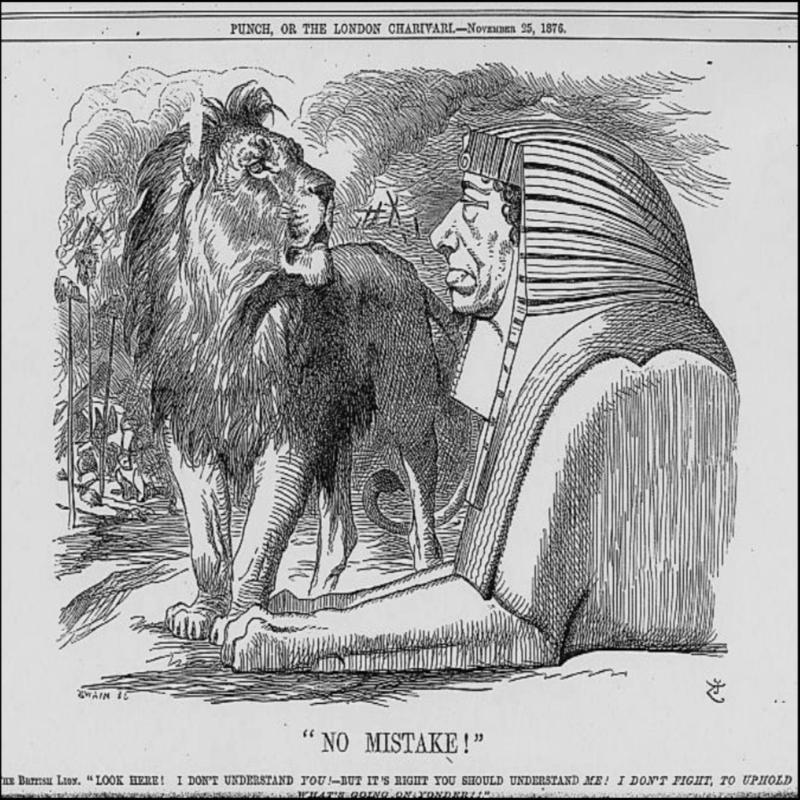

Britain was now the majority shareholder in the Suez Canal Company and Disraeli who understood full well its significance for the Empire informed Queen Victoria with relief and delight: “It is settled, you have it Madam!”

Gladstone was appalled, not with the purchase of the shares per se but in the manner they had been procured, in secret, with private finance, and without consultation. It was typical Disraeli he thought, a deal struck among friends in smoke filled drawing rooms in the dead of night without proper scrutiny and of doubtful financial probity. But the public thought otherwise – Good Old Dizzy!

In July 1875, the Balkans exploded into violence when Bulgaria and later Bosnia and Serbia rose in revolt against their Turkish masters.

The Ottoman Empire, so long the Sick Man of Europe was desperate to hold onto its possessions west of the Bosphorus, their ancestral enemy the Russians were no less eager to exploit their vulnerability.

Russian strategic interest was always of concern to the British in particular their long-held ambition to seize Constantinople, secure the Dardanelles, and gain access to the Mediterranean and a route to the West. Disraeli supported the Ottoman Empire both diplomatically and financially as a bulwark against Russian expansionism and that it was in Britain’s strategic interest to maintain its territorial integrity, plain and simple. When reports began to circulate that the Turks in their repression of the revolt were committing atrocities Disraeli metaphorically shrugged his shoulders and dismissed them as mere Coffee House Babble.

Gladstone, who had remained largely above the political fray since his defeat at the General Election two years earlier now returned with a vengeance at the same time proving that he was no less politically unscrupulous as his great rival penning a pamphlet in September 1876, ‘The Bulgarian Horrors and the Question of the East’, that became a surprise bestseller condemning Disraeli as complacent, indifferent to the suffering of others and demanding that he condemn the atrocities and withdraw Britain’s support from Turkey.

It was a fabricated argument and Gladstone knew it but it was a convenient stick with which to beat Disraeli who, though he might dismiss the pamphlet as ‘the greatest Bulgarian horror of them all’ was aware that few doubted Gladstone’s sincerity when it came to moral outrage as he toured the cities of northern England venting his spleen before large crowds at the man who turned a blind eye to murder.

Well might Disraeli only half-jokingly remark: “The difference between a misfortune and a calamity is this – If Gladstone fell into the Thames it would be a misfortune, if someone dragged him out again that would be a calamity.”

Whether Disraeli turned a blind eye to the atrocities in the Balkans or not, he was damned if he was going to pay any attention to Gladstone’s fulminations; it would be the interests of Britain and its Empire that would dictate his policy not his rival’s carping from the side-lines.

Disraeli’s worst fears were realised when on 21 April 1877, the Russians intervened militarily in support of the rebels. The forces of the Ottoman Empire performed better than many had anticipated but even though the Russian advance was slowed it continued. By early 1878, the Turks had been cleared from most of their Balkan possessions and Russia had imposed its authority over a vast area but it had been a bloody and wearisome fight and under pressure from Britain and others both sides agreed to a cessation of hostilities. What emerged from the negotiations was the Treaty of San Stefano signed on 3 March which brought to an end the conflict in the Balkans but did not halt Russia’s advance on Constantinople. In response to the continuing threat Disraeli despatched a British Fleet to the Bosphorus.

Disraeli was not willing to accept a treaty imposed on Europe by the Russians and concern that the crisis in the Balkans could engulf the Great Powers in a far wider conflict was a very real one. As a result that great manipulator of European affairs the German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck invited to Berlin all the contending parties to attend what was in effect a Summit Meeting.

The Congress of Berlin which took place between June and July 1878, was to represent Disraeli’s finest moment as fragile, ailing (he was 74 years of age) and leaning upon his silver-topped cane towered over by the 6’4” Bismarck who was not shy in using his considerable physical presence to intimidate others he went onto dominate proceedings, so much so that even the Iron Chancellor, not a man given to praising his opponents felt compelled to remark – What a man! The Old Jew, he is the one to watch!

Disraeli secured for the Ottoman Empire enough of its European possessions to serve as a barrier against further Russian expansion thereby ensuring its continued control of Constantinople, the Dardanelles Strait and access to the Mediterranean. He also acquired for Britain the strategically important Island of Cyprus. When the Russians appeared unwilling to agree to the terms of the treaty he ordered that his private train be prepared for departure. It was clear that if the Russians did not sign the treaty, then he would return home and make ready for war.

It was an act of bravado but not one without substance – the Russians backed down.

Disraeli, aware of his achievement was nonetheless taken aback by the reception he received upon his return to England where Union Jack bunting hung from buildings and adorned shop windows, people lined the tracks to applaud as his train passed by, and crowds flocked onto the streets of London to wave flags, sing the National Anthem, and shout his praises.

Standing on the steps of 10 Downing Street he declared that he had brought back ‘Peace with Honour’ (a remark that would be echoed some sixty years later by another Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain, following his meeting with Adolf Hitler at Munich, though perhaps in his case more out of hope than conviction).

Flowers from the Queen had been delivered to his office as had the many letters and telegrams of congratulation, though not from Gladstone but then it didn’t matter he had trumped him once more, at least for the time being.

Although it was discussed at length with his Cabinet colleagues Disraeli declined to ride the surge of popularity and call a snap General Election. His decision not to do so was to prove a mistake as events some foreseen others unforeseen would see Disraeli’s popularity disappear before his eyes and the prospects of election victory slip through his grasp.

Despite his triumphs abroad the economy had stagnated, and agriculture in particular was enduring its worst slump since the ‘Hungry Forties’ with poor harvests not helped by inclement weather and a lack of investment. Disraeli refused to reinstate the Corn Laws or adopt protectionist policies that would inevitably increase the price of food for the urban working class. It was a decision made for sound reasons but once again it made him appear indifferent to the travails of those who were among the Conservative Party’s staunchest supporters.

He then appeared to lose his touch in the area where he was thought a safe pair of hands - the Empire.

On 22 January 1879, a British Army was wiped out by Zulu tribesmen at the Battle of Isandlwana in South Africa and then on 8 September the British Mission at Kabul in Afghanistan was massacred to a man. Although both setbacks were speedily avenged the damage to Disraeli’s reputation was already done and his visits to the Palace to explain to the Queen the reversal in Britain’s fortunes, he found particularly irksome.

Growing dissatisfaction with his government, isolated from front-line politics in the House of Lords, and with declining health reducing his number of public appearances Disraeli was vulnerable and Gladstone knew it. Without a seat at Westminster but eager to exploit Disraeli’s increasing unpopularity especially with a General Election looming he now returned to the political fray standing for the Constituency of Midlothian in Scotland.

Gladstone’s Midlothian Campaign is now considered a model of its kind.

Nothing was left to chance as he employed a campaign manager Lord Rosebery, and a team of advisors who orchestrated his rallies to ensure that he reached as many people as possible, and he was to calculate that by the end of the campaign he had addressed no less than 86,930 people.

No one doubted Gladstone’s magnetism as a speaker or his ability to draw and transfix a crowd but now he was to engross a nation as he took every opportunity to attack Disraeli and the Conservative Government even if many of the arguments, he made were the same as those used during the Balkan Crisis. It was also an opportunity to explain in detail his political principles and moral philosophy and he did so with a religious fervour that saw his speeches regularly reported in the national press sometimes verbatim despite their length and complexity, just as he had intended. It was Gladstone at his most impressive, even if Disraeli had heard it all before.

No longer able to compete with Gladstone at the hustings because of failing health Disraeli could do little to stem the tide against his Conservative Government which went down to a resounding defeat even though the swing to the Liberals had been only 1.8% of votes cast.

Re-elected to Parliament as the Member for Midlothian, Gladstone resumed the leadership of the Liberal Party after Lord Hartington stood down in his favour seeing him become Prime Minister for the second time.

Disraeli was under no illusions that his defeat almost certainly heralded the end of his political career but to relinquish his leadership of the Conservative Party with Gladstone in power would simply have been a humiliation too far; but any vigour he had remaining he now dedicated to the completion of his final novel, Endymion.

In March 1881, his health took a turn for the worse when he contracted a severe bout of bronchitis that made him virtually housebound and later confined him to his bed. He had been in regular correspondence with Queen Victoria since the General Election but now requested she not visit him during his latest illness as it would make her maudlin and dwell too much upon the death of her beloved Albert. She would never see him again.

Benjamin Disraeli died on 19 April 1881, aged 76, declaring that though he might wish otherwise and desired to live he had no fear of death.

Despite being aware of his rival’s poor state of being Gladstone could not quite bring himself to believe the news of his demise thinking it at first a ruse on his part to elicit public sympathy; upon discovering that he had declined a State Funeral he considered it a trick to preserve for himself the quite false reputation as a man of the people. He wrote in his diary: “As he lived so he died, all display without reality of genuineness.”

Disraeli had spurned the applause of the crowd for a quiet funeral with a private service at the Chapel in the grounds of Hughenden Manor.

Gladstone did not attend the funeral claiming weight of public affairs but was little believed and much criticised for his apparent enmity towards Disraeli even in death and people eagerly anticipated what he might say of his predecessor when he addressed the House of Commons.

As it turned out he behaved impeccably and was fulsome in his praise of Disraeli though he focused almost entirely on his personal qualities while ignoring his policies. He then moved that a memorial be erected in Westminster Abbey in his honour – the motion was passed.

William Gladstone would remain at the forefront of political life for the next twenty years becoming Prime Minister on a further two occasions, but his later Administrations never matched the achievements of his first as he became increasingly mired in the swamp of Irish Home Rule seeing his attempts at a settlement rejected in Parliament time and again and leaving the country in greater turmoil than he had found it.

The truth was Gladstone needed Disraeli just as Disraeli had needed Gladstone and that for all their mutual antipathy the one without the other was reduced in both substance and stature.

Never as popular as Disraeli or a such a gift to the satirists of the press and the gossips of the party circuit Gladstone nonetheless became the G.O.M, or Grand Old Man of British politics and the subject of Music Hall ribaldry, though he would later be derided as the M.O.G, or Murderer of Gordon following the fiasco of Khartoum.

Gladstone resigned from the Premiership for the last time on 2 March 1894, aged 85, a disappointed man for he had neither pacified Ireland nor witnessed the great moral reformation he had so longed for but at least he was able to return to his beloved Hawarden and spend more time with his many grandchildren. Not that retirement was on his mind and despite increasing deafness and failing eyesight his library soon became his ‘Temple of Peace’ as he penned pamphlets, translated Greek and Latin texts, and received guests of whom there were many who wished to be seen with the great man.

Working until the end William Ewart Gladstone passed away aged 88 on 19 May 1898.

He had left instructions that his funeral should be a simple affair unless others thought to the contrary, and they did. On the 28 May he was buried in Westminster Abbey following a State Funeral that saw among his pallbearers the future King Edward VII and King George V.

Benjamin Disraeli and William Gladstone had dominated the political scene for the best part of four decades and in doing so they had transformed it. Both men had created modern political parties as we understand them today and the system of democracy with which we are now very familiar.

Their impact on British society and of the nation’s place in the world had been no less significant, yet they couldn’t have been more different.

The perception of Disraeli was of a man willing to gamble, a keen advocate of gunboat diplomacy who like Palmerston before him was willing to let the lion roar; Gladstone, who wore morality on his sleeve believed in cooperation in foreign affairs and negotiation between nations.

On the economy Gladstone preached prudence declaring that in low taxes and sound financial management lay the path to prosperity; Disraeli was always more proactive believing that what needed to be done should be done, and that the money should be found to do it.

That at least is the perception and politics is as much about the smoke and mirrors of desire and ambition as it is a matter of deed and fact, though I can sense Mr Gladstone turning in his grave at the very idea.

It was in the end the clash of greatness the likes of which had never been seen before and will likely never be seen again.

Less than three years after William Gladstone died Queen Victoria that other seemingly indestructible pillar of British cohesion, strength, and authority too passed into history.

It truly was the end of an era.

Tagged as: Victorian

Share this post: