Dunkirk: A Miracle of Deliverance

Posted on 7th July 2021

By the end of May 1940, the German military machine had swept all before it, France stood on the verge of catastrophic defeat and the British Expeditionary Force had been cut off and forced to flee towards the Channel Ports. It seemed only a matter of time before it too was destroyed. Only a miracle it seemed, could save it - the course of world history hung in the balance.

Since September 1939, Britain and France had been at war with Germany but except for a brief campaign in Norway and the continuing war at sea hostilities had yet to be joined. Instead, the two sides continued to eye each other nervously through the worst winter France had experienced in years.

Months of inactivity saw the morale of poorly paid French conscripts left idle and shivering in their trenches come close to collapse. Already a nation politically divided between Left and Right it was just 22 years since the end of the First World War and the nightmare of the Western Front which had mostly been fought on French soil. There was no desire among the French people or the Military High Command to fight, and the longer the so-called phoney war continued the less inclined to fight they became.

The British Expeditionary Force sent to assist them was small and ill-equipped to engage in a major conflict.

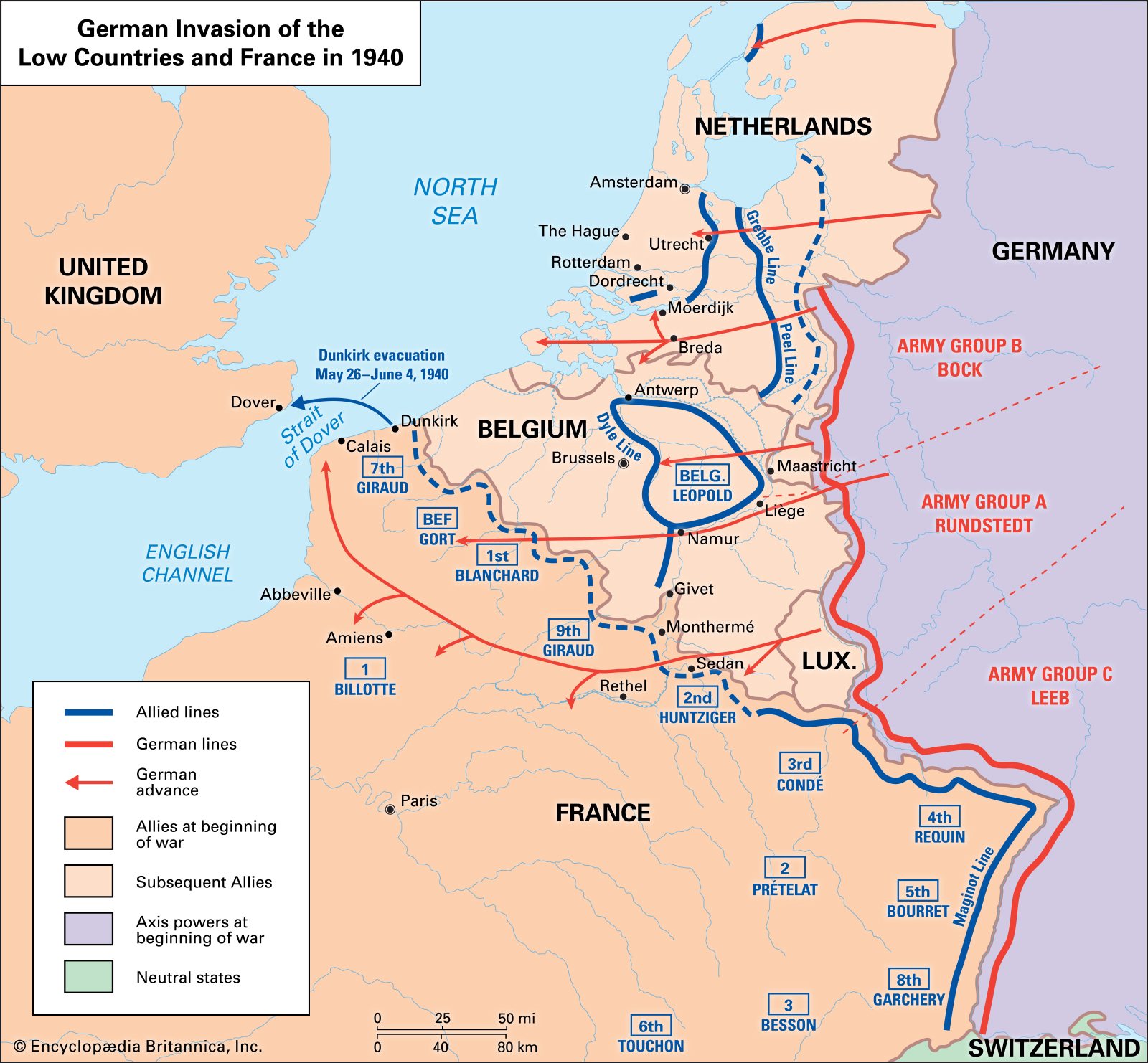

On 10 May 1940, the Germans launched a major offensive in the Low-Countries and Dutch and Belgian resistance quickly collapsed. The French and British advanced northwards to take up a defensive position on the River Dyle just as the Germans had expected them to do.

On the 14 May, they struck again through the supposedly impassable Ardennes Forest in north-eastern France. The French had done little to reinforce the Ardennes and now they were slow to react and within a few days the Germans had broken through.

Army Group A quickly captured Sedan and soon after turned west and in no time the Panzer Divisions of Erwin Rommel and Heinz Guderian were sweeping through open country and the French and British Armies that had advanced north to meet the German threat in the Low-Countries were now in danger of being cut-off.

The Allied Commander, the 67-year-old Maurice Gamelin who had made his Headquarters at Vincennes which had no radio or telephone communications and was reliant upon dispatch riders for information now found himself incapable of responding in time to the rapidly changing situation.

His strategy all along had been a defensive one based upon the Maginot Line fortifications being able to hold up any major German advance but now the Maginot Line had been by-passed and the war had now become one of movement.

By 20 May, the German spearhead had reached the coast, that same day Gamelin ordered the armies in northern France to attack south to link up with French forces elsewhere. But just a few hours later he was sacked by the French Premier Paul Reynaud. The 67-year-old Gamelin was replaced by the 73 year old Maxine Weygand who now wasted three days conferring with his senior Commanders before issuing exactly the same orders as Gamelin had.

Despite the success of a British attack at Arras which had temporarily checked the German advance other French counterattacks had been largely ineffective and on 23 May, Lord Gort, Commander of the British Expeditionary Force, who had lost all faith in the French High Command, ignored the order to advance south and instead issued orders of his own - to retreat to the coast.

With Calais having fallen on 24 May, the only port remaining for possible evacuation was Dunkirk and the 1st Panzer Division was already closing in.

The British hastily established a defensive perimeter around the town while also maintaining a narrow corridor for the retreating army. With no realistic prospect of breaking out of the encirclement the final decision to attempt an evacuation of the army by sea was taken on 25 May.

The decision to abandon their French allies at a time when they were in such peril was a tough one for the Prime Minister Winston Churchill to take but the future defence of the Home Islands must take precedence - Operation Dynamo was put into effect.

It was a monumental task and a flotilla of 39 Destroyers, 36 Minesweepers, and 77 Trawlers were hastily assembled for the task. The docks at Dunkirk had been destroyed however and could not be used while the approaches to the beaches were too shallow for most of the ships to navigate without running aground. On the first full day of the evacuation only 7,669 troops were rescued.

It had been estimated by Admiral Bertram Ramsay who working from tunnels beneath Dover Castle was in overall command of operations that only a maximum of 45,000 troops could expect to be rescued but at this rate not even this modest total would be achieved.

On 27 May, the Ministry of Shipping ordered that all craft of shallow draft were to be requisitioned. The attention focused on small fishing vessels, pleasure boats, private yachts, motor launches etc and 561 were taken into service. It was intended they be manned by Royal Navy personnel and used to ferry troops to ships waiting offshore.

MMany boat-owners were reluctant to cede control of their craft to strangers while others fired by patriotic zeal to lend a hand were insistent on sailing their boats to Dunkirk themselves.

Leaving from Ramsgate the small ships had to take a circuitous route to Dunkirk to avoid mines which doubled the distance they had to travel. They were also under constant air attack and threatened by German Motor Torpedo Boats. Even so, many of the small ships were determined to bring the troops home themselves.

The Mersey Ferry Royal Daffodil made 5 trips and picked up 7,461 military personnel while the Paddle-Steamer Medway made 7 trips and rescued more than 7,000 troops.

Charles Lightoller, who had been Second Officer aboard the Titanic, insisted upon skippering his own pleasure boat Sundowner and with his son and a local sea scout managed to haul aboard 130 exhausted soldiers and ferry them home despite the boat being so tightly packed it came close to capsizing.

On 28 May, 17,804 troops were successfully evacuated. That same day King Leopold of the Belgium’s ordered his army to lay down their arms leaving a 20-mile gap in the British lines making an already precarious situation desperate.

Just the previous day 97 British soldiers who had held off a much larger German force and surrendered only when their ammunition ran out were murdered at Le Paradis by troops of the SS Totenkopf Division. The German Commander at Le Paradis, Hauptsturmfuhrer Fritz Knochlein was executed in 1949 for war crimes on the evidence of the only two survivors.

The day after the massacre at Le Paradis a further 80 British and French troops were executed at Wormhoudt by the SS Liebstandarte Division.

On 24 May, Adolf Hitler had visited General von Rundstedt at his Headquarters at Charleville where following discussions he ordered the Panzer Divisions to halt their advance. Much has since been made of Hitler's so-called "Halt Order."

It has been suggested that he wished for the B.E.F to escape intact if shorn of their equipment so he could negotiate a peace settlement with Britain as a potential ally; but the truth is likely more prosaic.

Hitler who was unschooled in military tactics failed to understand the overall strategic picture. As far as he was concerned the Battle for France had gone beyond his wildest dreams and now at the point of victory, he feared a reverse. The Allies around Dunkirk were fighting like tigers while the French Army to the south of them though disadvantaged remained largely intact. The terrain around Dunkirk was also considered unsuited to mechanised warfare - Why should he risk his Panzers when the British were already trapped with nowhere to go? In any case, had not Hermann Goering assured him that the Luftwaffe would destroy the British on the beaches - there could be no, escape.

On 29 May, 47,310 troops were rescued.

The increase in the number being evacuated was down to the Commander on the ground, Royal Navy Captain William Tennant's decision to use the Moles, the two sea walls protecting the harbour as embarkation points.

Troops queued on the walls to board waiting destroyers that pulled alongside. At the same time, they also formed lines on the beaches to reach the small ships which would ferry them to the larger ones lying offshore.

The troops awaiting embarkation were under constant shelling and air attack but the soft sand on the beaches tended to smother the impact of the bombs. Even so there was little protection from the constant strafing.

Machine gun posts were set up to provide some defence and individual soldiers took pot-shots at the planes as they flew over, but it made little difference. The soldiers could not understand why the Royal Air Force were not tackling the Luftwaffe and the taunt that the “Brylcreem Boys” were too busy partying to lend a hand soon became a common refrain.

The R.A.F was busy however trying to keep the Luftwaffe away from the beaches and providing protection for the ships ferrying the troops back to Britain.

But simply getting aboard an evacuation ship was no guarantee of safety. On 29 May, HMS Grafton was sunk by U.62 and HMS Grenade by air attack. That same night the destroyer HMS Wakeful was torpedoed by an E-Boat and sank with 631 troops aboard. All but 1 of the soldiers drowned.

In the meantime, the defence around Dunkirk was becoming increasingly desperate.

On 30 May, Hitler had cancelled his Halt Order and his Panzer Divisions were now closing in on the Port. Senior Officers were by now having to fight alongside their troops and anyone who tried to retreat was forced back into the front-line at bayonet point.

Also, as the B.E.F was fast being evacuated the responsibility for the defence of the Dunkirk perimeter was increasingly falling upon the French First Army, which despite being surrounded and hopelessly outnumbered held up Erwin Rommel's Panzers for four days.

In the last two days of May, 120,927 troops were evacuated but the French destroyers Sirocco and Bourrasque were also sunk. The advance of the German Panzers also meant that the opportunity for such large-scale evacuations was fast disappearing. They had no effective defence against them and General Alexander in overall command, and General's Brooke and Montgomery, commanding the forces holding the perimeter knew this. It was now simply a case of evacuating as many troops as possible in the little time they had left to them.

On 1 June, the British destroyers Keith, Havant, and Basilisk were sunk along with the French destroyer Le Foudroyant. Even so, a further 64,229 troops were successfully evacuated.

The 2 June was to be the final day of Operation Dynamo and a further 54,000 troops were plucked from the beaches.

The British Expeditionary Force had been saved but the following morning Prime Minister Winston Churchill ordered the ships back in to pick up as many of the remaining French troops as they could. The evacuation from Dunkirk would not have been possible without the determined resistance of the French First Army and he wouldn’t now abandon them.

But by now the fighting was taking place in the streets of Dunkirk itself and many French troops had to be left behind. Even so, 26,000 were rescued.

As darkness fell on that final night General Alexander scanned the beaches from aboard the last ship to leave. He could see that they were littered with abandoned trucks, destroyed tanks, spiked guns, and the corpses of the dead - the detritus of war.

The remaining French troops had since surrendered and there was no one left to be saved. As he glanced up, he could see that the swastika now flew above the town - the Battle for Dunkirk was over.

The withdrawal from Dunkirk was a shattering defeat for the British Army but that the B.E.F had been saved at all was a miracle. But it had been a miracle earned.

Through a combination of organisation, audacity, courage, good fortune (the unpredictable Channel weather had remained fine) and a fatal miscalculation by Hitler, Britain's small professional army had been saved.

In total 338,226 troops were successfully evacuated from the beaches of Dunkirk, 198,229 of them British, the rest French, Dutch, Polish and Belgian. But it had been achieved at a fearful price.

The British had lost 11,014 men killed and 14,000 wounded with the French enduring similar casualties while a further 41,338 men had been captured defending the perimeter. Of the 861 vessels that took part in the evacuation some 243 were lost more than 200 of them small ships. The R.A.F lost 107 planes defending the beaches and protecting the ships as they crossed the Channel.

All the army's heavy equipment had had to be abandoned and destroyed. Besides enormous amounts of ammunition this included 310 large calibre guns, 880 field guns, 850 anti-tank guns, 500 anti-aircraft guns, 11,000 heavy machine guns, 700 tanks, 20,000 motorcycles along with 45,000 trucks and other motor vehicles.

Indeed, in the months immediately following the evacuation at Dunkirk there wasn't a single tank on the entire south-east coast of England, the place where a German invasion was expected to come.

Over the next two weeks a further 220,000 British troops were successfully evacuated from other French ports further south before the effective surrender of France on 16 June made any more such operations impossible

On 4 June, Winston Churchill addressed the House of Commons with a speech that would later be broadcast to the Nation. In it he did not shy away from what had been a colossal military disaster and warned that wars were not won by evacuations, but he also described it as a "Miracle of Deliverance."

The Dunkirk Spirit would live long in the British psyche.

Share this post: