Emma Goldman: The Most Dangerous Woman

Posted on 12th February 2021

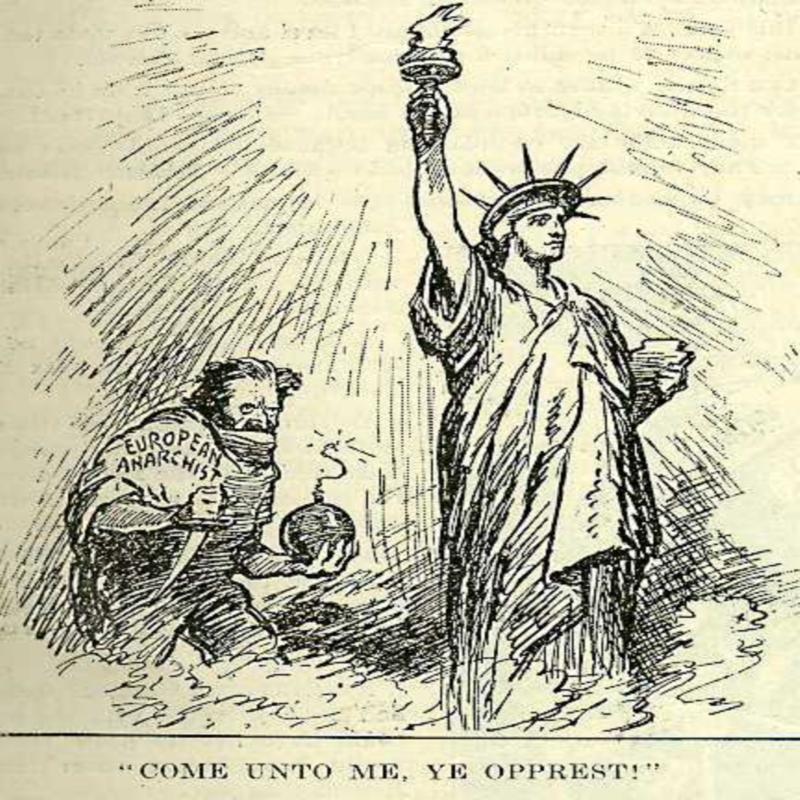

Emma Goldman was an immigrant who having fled to the United States for a better life did not find its streets paved with gold. Indeed, with few possessions and little money it seemed she had merely swapped tyranny and religious intolerance for extreme poverty and capitalist exploitation. But she believed the United States was ripe for revolution and could be made to live up to the ideals it espoused, and she would fight to make that happen. In time she would be called the most dangerous woman in America.

She was born in Kaunas, Lithuania, then part of the Russian Empire in June 1869, to Orthodox Jewish family and though she was to be close to her half-sister Helena her mother was distant while her father, Abraham Goldman, was a brutal and unsympathetic man who regularly beat his children who received scant protection from their mother who according to Emma had never recovered from the death of her first husband whom she loved very dearly. In fact, she had only married their father because a single woman had not the means to fend for herself. Forced into a loveless relationship her life had descended into one of physical fear and emotional abuse. It was living proof to Emma of the second-class status of women in the world.

The brutality that Emma witnessed both on the streets of her hometown and endured at the hands of her own father in those early years made an indelible mark upon her. Meanwhile, she compensated for an unhappy home life by indulging her love of books but desperate for an education any attendance at school was frustrated by the family’s itinerant lifestyle. Finally, they settled in St Petersburg but even now her father refused to permit her to enrol in school insisting that like her sisters she work to help the family make ends meet. Emma did as she was told but when her father demanded that she also marry she steadfastly refused. Furious, her father took her books and threw them upon the fire shouting that:

“Girls do not have to learn much! All a Jewish daughter needs to know is how to prepare fish, cut noodles, and provide a man with plenty of children.”

It was an incident the young Emma would never forget and even though but though she would continue to study she never received the formal education she sought.

The greatest influence in Emma’s early life was a man she never met, the author Nikolai Chernyshevsky whose novel ‘What is to be Done’ she would make frequent reference to in years to come. It was a tale of working-class heroism in which its main protagonist, Vera, flees a repressive home life to set up a sewing co-operative of independent women. To Emma this scenario had a dream-like quality and one to which all women should aspire.

Russia at the time was a place where political assassination was commonplace and on 13 March 1881, Tsar Alexander II was murdered by members of the revolutionary Narodnya i Volya. The news thrilled Emma, so no one not even the Tsar of Russia was safe from the retribution of the people.

Emma begged her father to be permitted to join her older sister Lena who had moved to America with her husband. As usual he stubbornly refused to grant her anything even though her other sister Helena had agreed to pay for the trip. Eventually her father relented and on 29 December 1885, Emma sailed for America with Helena where upon their arrival they moved into Lena’s home in Rochester near New York.

Life in Rochester was to be only a little less harsh than it had been in St Petersburg and Emma was soon working ten hours a day as a seamstress for just $2 a week. Her rebellious spirit had not deserted her however and when her demands for a pay rise were ignored, she walked out. It was a temporary setback only and she soon found a new job and in Jacob Kershner a man who shared her love of books and ideas. Being able to talk about literature and current events was her only relief from a life of grinding toil for little reward and so in February 1887, they wed but it wasn’t a happy marriage particularly as Kershner was impotent which on their wedding night at least given Emma’s sexual naivety came as some relief. But it also didn’t make for a loving relationship and as a result she and Kershner soon parted, a decision that was condemned by her parents who had since joined her in America and now demanded that she remain with her husband and display the wifely virtues. Under pressure they briefly reunited but she soon tired of the arrangement and with just $5 and her sewing machine she walked out and went to New York.

On her first day in New York she went to Sachs Cafe, a well-known watering hole for radicals and left-wing intellectuals. There she was to meet the two men who would change her life forever.

Johann Most, whose face had been eaten into by a gangrenous infection, was a well-known anarchist and a firebrand advocate of propaganda by deed. Emma was enthused by his words, his belief in direct action and encouraged to do so began appearing on public platforms herself and speaking at meetings. She wasn’t at first very good, her voice was weak and her delivery uncertain, but her passion was at least obvious.

The other man she met that day was to become the love of her life.

Alexander Berkman was another Jewish immigrant from Lithuania who had only recently arrived in the United States. He shared with Emma a loathing of authoritarianism and social injustice with both being drawn to the philosophical and political credo of anarchism.

Emma honed her skills at public oratory in small halls and at open air meetings around New York and on the left-wing lecture circuit. She did so alongside Johann Most but overtime became disenchanted with the man who had inspired her into a life of political activism. Weary of his condescending arrogance she told him she would no longer simply be the mouthpiece for his views. He did not take kindly to being spoken down to by a woman and became threatening. Emma hadn’t come to America to be bullied and so removed herself from Most’s inner-circle and moved in with Berkman, a man with whom she shared more than just a passion for justice, equality and freedom.

The United States at the time was undergoing a period of unprecedented industrial growth that over the coming few decades would turn it from an essentially agrarian based economy into the world’s economic superpower. However, in the wake of this came extremes of wealth and poverty rarely seen before and the clashes that would result between the forces of capitalism and those of organised labour would often be bloody and brutal.

By June 1892, in the town of Homestead, Pennsylvania, a prolonged industrial dispute between the Carnegie Steel Company and the Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steel Workers had become bitter following the breakdown of talks.

The Union had in the past won concessions from the Company that had infuriated the factory manager, Henry Clay Frick. On this occasion the belligerently anti-Union Frick remained adamant that he would not back down under pressure and so when talks failed to resume the Union determined to occupy the factory. Frick was equally as determined to lock them out and when he began fencing off the factory and building guard towers the Union called for a strike and a mass picket. Frick responded by bussing in non-Unionised labour from elsewhere.

The angry response of the crowd many of whom were the wives of those who worked at the factory frightened many into refusing to cross the picket line. Frick, however, was willing to pay for their protection and as events in Homestead now began to spiral out of control, he determined to intimidate the workers and break the picket line by hiring 300 armed Pinkerton Agents who late on the night of 4 July set off down the Monaghela River in two barges. Forewarned of their arrival more than 2,000 workers assembled, many of them also armed.

Around four in the morning on 5 July, as the Pinkerton Agents began to disembark the barges firing broke out and the violence soon escalated as the strikers reinforced by more workers from nearby Homestead kept the barges under a constant barrage of missiles and bullets. Attempts were made to sink the barges by pouring oil onto the water and then exploding sticks of dynamite to set them alight as the Pinkerton Agents frightened and huddled together on the deck fought back as best they could but unable to disembark or retreat their position was hopeless. In the late afternoon of 6 July, they negotiated their surrender.

The violence at Homestead which had left 9 Pinkerton Agents and 7 of the strikers dead did not end with their surrender. Disarmed the hated agents were marched through the streets of Homestead past a hostile crowd who hurled abuse, spat on them, and threw stones. Some Agents were beaten into unconsciousness.

The humiliation of the Pinkerton Detective Agency and of Henry Clay Frick was to be only temporary for the level of violence had been such the State Governor had little choice but to yield to Frick’s demand to intervene. The following day he called out the National Guard.

With the Governor now willing to do his dirty work for him Frick steadfastly refused to re-open negotiations.

As far as Alexander Berkman was concerned the violence at Homestead was entirely the fault of Frick and though he had no connection to the strikers or indeed to organised labour he took it upon himself to act on their behalf, and Emma would be his willing accomplice.

They would adopt the anarchist propaganda by deed and assassinate Frick.

Berkman at first planned to use a bomb to blow up Frick as he worked in his office, but he was a hopeless exponent of bomb-making and proved more of a danger to himself and Emma than he was to his intended victim. So instead, he resolved to shoot Frick.

Emma demanded that she be allowed to accompany him but Berkman certain in the belief that the assassination would cost him his life insisted that she must remain alive and at liberty to spread the message of what they had done and why. Her task instead was to raise the money to buy the gun and purchase a decent suit of clothes for Berkman.

This was easier said than done but Emma remained undaunted, and she was even willing to try prostitution to raise the required funds. Her attempt at playing the whore wasn’t entirely successful, however. Indeed, one client paid her off declaring that she should try another profession as she wasn’t very good at this one. Fundraising then wasn’t one of Emma’s great talents and in the end, she simply borrowed the money from her sister.

On 23 July, the now immaculately dressed Berkman gained access to Frick’s office on some pretext or other but he was to prove as poor an assassin as he had been a bomb-maker as firing three times at his intended victim from close range he only succeeded in wounding him in the shoulder allowing Frick to grapple him to the floor and for a time they struggled furiously with each other as Berkman stabbed and slashed at Frick’s leg with a knife he had concealed upon his person.

Eventually, Frick was rescued by some workmen who viciously clubbed Berkman unconscious and had it not been for Frick’s intervention would probably have killed him.

The earlier events at Homestead had done much to tarnish Andrew Carnegie’s reputation as a philanthropist and benevolent employer and had gained the striking workers considerable sympathy - Berkman’s assassination attempt was to change all that. There was no national rising of the workers as he had hoped for and expected. Instead, it was a public relations disaster for the strike which had up to that point received a relatively sympathetic press.

Many of the strikers themselves did not want to be associated with murder and the dispute soon collapsed and along with it the Union.

Emma was immediately suspected of involvement in the plot but despite her flat being searched and placed under constant surveillance the evidence that would warrant an arrest could not be found.

The attempt to murder Henry Clay Frick had been roundly condemned by all sides including Johann Most which infuriated Emma as being nothing but rank hypocrisy. He had been the great exponent of propaganda by deed and now he was lambasting someone who had taken his words literally. As he addressed a meeting, she forced her way onto the stage and attacked him with a whip.

Berkman’s assassination attempt was to prove the defining moment in both his and Emma’s life as he was sentenced to twenty years imprisonment leaving Emma alone to continue his work, something she now considered her mission in life.

In 1893, a collapse in the value of shares sent Wall Street into a panic and the financial crisis that resulted was to see over 600 banks close, 56 railways shut down, 15,000 companies go bust, and unemployment soar to over 3 million. For the first time many Americans began to question Wall Street and both the practical and ethical value of capitalism. Unemployed workers took to the streets of many cities across America and hunger marches became commonplace. It was a time of great distress for many Americans but for Emma it was an opportunity. For the first time she had a ready-made audience not of political activists, other radicals and the merely curious but of workers prepared to give her message a hearing. On 21 August, she addressed a rally of 3,000 workers in New York’s, Union Square. She told them: Demonstrate before the palaces of the rich, demand work. If they do not give you work demand bread. If they deny you both then take it.

A week after the rally in Union Square, Emma was arrested for incitement to riot.

At her trial she denied her anarchism was implicitly violent, but it was her self-declared atheism that played poorly with the jury and those watching on. The presiding Judge in his summing up of the case declared her for the first but by no means the last time, a dangerous woman - she was sentenced to a year’s imprisonment.

Much like Berkman, Emma was to prove a model prisoner spending her time reading and acquiring the education that had been denied her in her youth. She also studied to be a nurse. Upon her release she was lauded by her supporters as a martyr to free speech and she used her new-found notoriety to good effect by embarking upon her first nationwide lecture tour and over the next few years she was to earn the reputation as a radical firebrand becoming the effective mouthpiece for anarchism in America, much to the annoyance of many of her more senior associates who doubted if she had the intellectual capacity to fulfil such a role. Her status within the radical movement was only enhanced further by her frequent journeys to Europe where she met and was endorsed by the other leading anarchist thinkers of the day.

Emma enjoyed her improved standing among many ordinary Americans and her lectures were well-attended, would regularly sell out and she often received a positive press at a time when the feminist movement was becoming a powerful political force in American society.

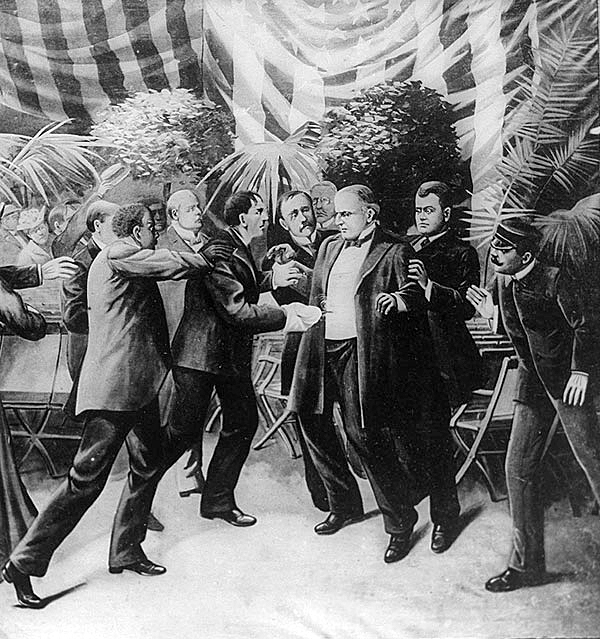

All this changed when on 6 September 1901, while attending the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo President William McKinley was shot twice at close range by a young man of Polish descent Leon Czolgosz, who was arrested at the scene. Despite at first appearing to recover McKinley died of his wounds eight days later, and Czolgosz was charged with murder.

During his interrogation he declared himself an anarchist and claimed that he had shot the President in the name of the people and had been inspired to do so after attending a lecture Emma Goldman had given in Cleveland, Ohio. It was later revealed that he had also visited her home.

In fact, Czolgosz had previously been a registered Republican and had a long history of mental illness. He had only recently displayed an interest in anarchism and was not known in radical circles so and how sincere his conversion to the revolution was remains a mystery.

Nevertheless, Emma was immediately suspected of having been involved in a plot to murder the President of the United States and that she may even have been the prime mover in the assassination. She was arrested and interrogated day and night for two weeks, but no evidence could be found to implicate her in any conspiracy and she was released without charge. It wasn’t her arrest that was to damage her reputation however but her refusal to condemn Czolgosz’s actions. Indeed, she defended him saying: “As an anarchist I am opposed to violence, but if the people want to do away with assassins, they first have to do away with the conditions that produce murderers.”

The execution by electric chair of Czolgosz on 29 October 1901, she considered a sad day and one worthy of mourning. He had been, she said, a “supersensitive being.”

Emma was roundly condemned for her support of Czolgosz not just by the usual suspects but across the political spectrum. The socialist movement and organised labour distanced themselves from her and even her fellow anarchists thought her views beyond the pale.

The criticism hurt her deeply and in 1902 she withdrew from active political life disappearing into obscurity for a time working as a nurse in the slum tenements of New York’s East Side under the pseudonym E.G Smith. She did not re-emerge until the early spring of 1906.

During her time in self-imposed political exile, she had raised the funds to fulfil a long-held dream to publish her own magazine and the first edition of the monthly periodical Mother Earth, which she claimed was devoted to literature and the social sciences but was in fact a vehicle for her own radical ideas on anarchism, free love, and female enfranchisement and emancipation, was issued in March. Two months later Alexander Berkman was released from prison having served 14 of his 20-year sentence for attempted murder. Emma was thrilled at the prospect of seeing him again, but their first meeting did not go as planned.

He was cold towards her, and it wasn’t just his changed physical appearance, for he was pale and gaunt, had lost his hair, and had noticeably aged, that shocked her but he no longer had the old vigour, the sense of injustice, and the shared desire to set things right. The fire of outrage appeared to have been doused. He struggled to adjust to life outside prison, was sullen, morose, and often just sat alone and in silence. Even so, they tried to resume their previous love affair but his lack of sexual interest in Emma soon became apparent.

Despite the hurt Emma stood by her ‘Dear Sacha’ and over the next few months the bonds of mutual affection were restored, and he was slowly drawn back into the realm of politics and by 1907 was editing Mother Earth while Emma returned to the lecture circuit.

In 1908, she met for the first time Ben Reitman, the so-called ‘Hobo Doctor,’ an eccentric figure who had left the family home in Chicago when still a child to become a drifter where travelling widely he experienced hard times before returning to his hometown to train as a doctor. Remaining in Chicago he offered his services cheap and often for nothing to the poor and disenfranchised of the city. Much of his time, however, was spent treating venereal disease and carrying out illegal backstreet abortions. His experiences had long ago attracted him to anarchism, and he had long been eager to meet the notorious Emma Goldman. She was later to describe that meeting in her autobiography:

“He arrived in the afternoon, an exotic, picturesque figure with a large black cowboy hat, flowing silk tie, and huge cane, a tall man with a finely shaped head covered with a mass of black curly hair, which evidently had not been washed for some time. His eyes were brown, large, and dreamy. His lips, disclosing beautiful teeth when he smiled, were full and passionate. He looked a handsome brute. His hands, narrow and white, exerted a peculiar fascination. His finger nails like his hair seemed to be on strike against soap and brush. I could not take my eyes off his hands. A strange charm seemed to emanate from them, caressing and stirring.”

Possibly for the first time in her life Emma was consumed with sexual desire and their subsequent love affair was to be intensely physical but so also was her emotional commitment. Both Emma and Reitman were outspoken advocates of free love but whereas he took it literally and had numerous affairs and casual sexual encounters, Emma could not. It only incited feelings of intense jealousy in her and she was forced to question not only her own sincerity but the core values that she had for so long preached and believed in.

For the next eight years Emma and Reitman were to tour America together lecturing night after night in city after city. The work was as intense as their relationship as the one fed off the other.

Emma was full of nervous, sexually charged energy, her passions were aroused by Reitman, she lived in constant fear of losing him, and all the time she wanted to change the world. But she was concerned that her message was being lost, that her fame was such that she had attained the status of a celebrity speaker, and despite the audiences at her lectures being large and enthusiastic they were not necessarily there to listen but just to be able to say that they had heard Emma Goldman speak.

In 1914, she became heavily involved in the campaign for birth control, a phrase coined by the feminist activist Margaret Sanger. She lectured specifically on the issue of contraception and the right of a woman to discharge of her body as she wished and that meant not only being able to enjoy sex when and with whom she pleased but also to abort any unwanted pregnancy that resulted from the enforced unavailability of contraceptives.

In her pamphlet “I Demand the Freedom” she wrote: “I demand the independence of woman, her right to support herself, to live for herself, to love whomever she pleases and as many as she pleases. I demand freedom for both sexes – freedom of action, freedom in love, and freedom in motherhood.”

In August 1914, Emma was arrested for violating the terms of the Cornstock Laws which banned the distribution of literature deemed of a lewd and lascivious nature which included any mention of contraception and abortion. She was imprisoned for two weeks. Reitman had also been arrested for violating the same law and had received a six-month jail term, the heaviest ever imposed. While in prison he wrote to Emma informing her that upon his release he intended to abandon campaigning and end their relationship to marry one of his many lovers who had recently given birth to his child.

Emma was distraught but she tried not to show it returning to New York and the only man she felt she could ever really trust, Alexander Berkman. And it wasn’t long before she had another cause to fight for.

The same month that she had been arrested the Great War broke out the pressure for the United States to intervene on the side of Britain and France was intense especially following Germany’s adoption of unrestricted submarine warfare and the sinking of the Lusitania.

In April 1917, President Woodrow Wilson who had been re-elected on the slogan “The man who kept us out of the war” responded to the Zimmerman Telegram which had encouraged Mexico to begin hostilities against America with German support by declaring war. Two months later Congress passed the Conscription Act.

For Emma and her anti-militarist colleagues the war in Europe was nothing but a capitalist inspired bloodbath fought by working class men to defend bourgeois property – that a butcher from Hamburg should be trying to kill a butcher from New York to protect the investments of a financier in Paris made no sense.

In the wave of patriotic fervour that followed the declaration of war few people were willing to stand up and oppose it, but Emma was and she did, addressing crowds and demanding that America remain neutral in a war that had plunged Europe into a nightmare of unspeakable proportions and was taking the lives of millions of young men. In May 1917, she launched the No Conscription League and more than 8,000 people attended their first meeting in Harlem.

For a President who had personally vowed never to take the United States into a foreign war it was a sensitive issue and Emma’s much publicised opposition to it could not be tolerated. On 15 June, the offices of Mother Earth were raided and Emma and Berkman arrested.

They were accused of unpatriotic behaviour, of providing comfort and aid to the enemy, and of encouraging men not to register for the Draft Act. In August, Mother Earth was closed and Emma and Berkman charged with violation of the Espionage Act. Found guilty they were sentenced to two years imprisonment. Incarcerated for the rest of the war their release on 22 September 1919 did not signal the end of their travails. It was now the height of the ‘Red Scare’ and the Government was determined to rid themselves of those they considered undesirables and so on 5 December they were re-arrested and sent to Ellis Island in preparation for deportation. They both invoked the First Amendment and freedom of speech to fight their case, but their appeals failed.

At 4.00 am on 21 December, Emma, Berkman, and the other internees were woken and ordered to dress. They were then taken out to the steamer Buford which had been dubbed by the press the Soviet Ark. On board, awaiting them were armed guards and they were to spend much of their time locked in their cabins as still in semi- darkness the Buford set sail for Europe.

Emma had the opportunity to briefly address a crowd that had gathered at dockside where she told them that she was proud to be deported but the truth was that she was devastated, she was being forced to leave the country that had been her home for thirty years and had provided her with the opportunities that were denied to so many women elsewhere for though she railed against its injustices she admired its love of freedom and to her mind she had never wanted to harm America but merely make it better. Upon their arrival in Hanko, Finland, the internees were put on a sealed train and taken to Soviet Russia.

Emma and Berkman both had high hopes for the revolution in Russia, but the reality was to come as a shock. Shortly after their arrival they had a meeting with Lenin who roundly mocked their bourgeois notions of free speech:

How can you have free speech in a revolutionary situation where the peasantry opposes them and are hoarding food, where capitalists sponsored armies are fighting them, where spies and saboteurs seek to destroy them, and they are being assaulted at every turn by the forces of reaction?

It was naive and foolish to believe that the opponents of the revolution did not have to be crushed with all the force available.

It was made apparent to them that their outspoken views would not be tolerated in Soviet Russia as they had to a large extent been in the United States. Indeed, their views and activities would be considered as counter-revolutionary and the Bolshevik response to counter-revolutionary activity was made stark when on 17 March 1921, the Red Army led by Leon Trotsky launched an all-out attack on the last refuge of the anarchists, the Naval Base at Kronstadt.

Increasingly in fear for their lives and thoroughly disenchanted with their experience of revolution in December 1921, Emma and Berkman departed Russia. In future publications and speeches, they would roundly condemn the Bolshevik Revolution for the brutal oppression of its political opponents and silencing of all dissent.

IIronically, Emma’s outspoken criticism of the Bolsheviks won her praise across the political spectrum that she could never normally have expected. Even so it wasn’t enough to regain her entry to the United States. So, travelling around Europe she gave lectures and became the guest of many prominent people but she soon became disillusioned by her now itinerant lifestyle. She was also lonely having by now parted from Berkman. They had become increasingly distant over the years though she continued to write to him, but the letters had ceased to be political and more often spoke of her sense of isolation.

In 1928, a few prominent and well-heeled admirers raised the money to purchase for her a cottage in St Tropez where she wrote her autobiography.

In 1933, she received permission to re-enter the United States on a temporary visa to lecture but only if she steered clear of discussing current affairs and spoke only of events discussed in her autobiography. She welcomed the opportunity but her request that the visa be renewed was declined and after a brief stay she crossed into Canada. By 1936, she was once more living in St Tropez to be closer to Berkman who was resident in nearby Nice, and who she knew was seriously ill. In March his condition took a turn for the worse and he ceased to reply to Emma’s letters.

Already concerned that he had failed to attend her 67th birthday party, Emma was soon after informed that unable to endure the pain of his cancer any longer Alexander Berkman had shot himself. Emma rushed to Nice to be at his bedside, but he died soon after; distraught and inconsolable she deeply regretted that they had seen each other so rarely.

But there was little time to mourn for in July 1936 the political tinderbox that was Spain erupted into Civil War.

Anarchism had remained a powerful political force in the country especially in the rural South and Catalonia. At last it seemed as if the moment for a true workers revolution had arrived, and Emma was thrilled at the prospect. She wrote: “The crushing weight that was pressing down on my heart since Sasha’s death left me as if by magic.”

She threw herself into the struggle travelling to Barcelona where she addressed huge crowds, and later visiting the recently formed collectives where she told them: “Your revolution will destroy forever the myth that anarchism stands for chaos.”

Her faith in the coming revolution was soon shattered when in early 1937 the anarchist leadership in Spain reneged on their core beliefs and joined a coalition Government that was being increasingly dominated by the Spanish Communist Party that was taking its orders directly from Moscow, the very same people who had so brutally crushed all dissent in Russia. She believed they were supping with the devil, and she was right.

In May, the anarchist strongholds in Barcelona were assaulted by troops sent by the Republican Government in Valencia on the pretext of eliminating subversives but in reality, to destroy any vestige of anarchist independence. After several days of bitter street-fighting the anarchist leadership ordered further resistance to cease on the grounds that maintaining unity in the face of the fascist threat must take precedence over the revolution. In the following few weeks the anarchist militia were incorporated into the regular army and the collectives were dismantled. Still, Emma continued to fight for the Republican cause addressing crowds, publishing pamphlets and even using her training as a nurse to treat wounded soldiers, but she did so with a heavy heart. But as defeat loomed even her words rang hollow with those on the Left who began to abandon a lost cause.

Following the collapse of Republican resistance in March 1939, she returned to Canada.

Emma still hoped one day to be permitted to return to the America she considered her home but even though she was now considered by many to be more a woman of principle or as a harmless eccentric rather than the dangerous ‘Red Emma’ of old, it wasn’t to be.

Her experience of war led her to oppose those who sought military intervention against Hitler and Mussolini. It earned her the reputation as an appeaser of fascism which wounded her deeply but by this time she was used to being on the wrong side of history.

On the night of 17 February 1940, Emma was playing cards with friends when she suddenly slumped forward in her chair. She had suffered a severe and debilitating stroke and though still conscious had lost the power of speech. It would never return.

She was to survive for a further three months and it seemed to some that she was making a recovery but on 8 May she suffered a second and even more severe stroke. Six days later she died, aged 70.

‘She was to survive for a further three months and it seemed to some that she was making a recovery but on 8 May she suffered a second and even more severe stroke. Six days later she died, aged 70.

‘Red’ Emma once referred to as the most dangerous woman in America was no more. The obituaries were for the most part generous.

Share this post: