Emperor Commodus: The Gladiator

Posted on 5th February 2021

Lucius Aurelius Commodus Antoninus was born on 31 August AD 161, the son of the Philosopher Emperor Marcus Aurelius, one of the so-called Five Good Emperors and a rare thing in Rome a reluctant wearer of the Imperial Purple.

Marcus Aurelius had been trained as a stoic and would have preferred a life of quiet contemplation, but he had been born to politics and had served as City Prefect under the Emperor Hadrian as well as being elected to two terms as Consul. As a sober, earnest, and hard-working man who devoted himself to public service when the Emperor Antoninus Pius died without an heir, he was a natural choice to succeed him.

The long reign of Antoninus Pius had been one of the most peaceful and prosperous in Roman history and just as Hadrian had set limits to Roman expansion so Antoninus Pius had little taste for and conquest. Indeed, he had never even left Italian soil and it was expected that Marcus Aurelius would pursue a similar policy - but it wasn't to be.

.

Trouble had been brewing on the fringes of the Roman Empire for some time. The migration of the German tribes in the North was causing concern there was unrest in Britain and increased tension between Rome and that perennial thorn in their side the Parthians.

Marcus Aurelius decided the threat from the Parthians had to be confronted but having no military experience himself he would remain in Rome and leave the campaign to his Generals. Perhaps out of a misplaced sense of loyalty however, he had earlier nominated his adopted brother Lucius Verus to be his co-Emperor, and he was eager for war.

Lucius Verus was a dissolute character more inclined to drinking and whoring than hard work. Marcus Aurelius was well-aware of his failings but nonetheless appointed him overall commander of the Roman forces in the East. It is possible he hoped the responsibility and stresses of military command would sober him up. If so, then he was to be proved wrong.

Great efforts were made to prevent Verus from interfering in the crucial decisions of the campaign but as a result of his meddling and military incompetence the Parthian War was to last five long, arduous, and exhausting years. It was not concluded until late AD 166, when the Parthians sued for peace following the sacking of their capital at Ctesiphon, an act of vandalism that Marcus Aurelius had expressly forbidden.

But even before the end of the war with the Parthians the Empire was being threatened from elsewhere. The Germanic Chatti Tribe were regularly raiding across the northern border, the Marcomanni along with the Lombards had crossed the Danube and were advancing west, and the Sarmatians in Persia had risen in revolt.

Marcus Aurelius, the man devoted to peace was now to find himself almost perpetually at war and despite failing health he now travelled with his armies on campaign. It was during this period of his life that he wrote his famous Meditations, a book of philosophical musings, self-improvement and spiritual guidance. It set an example perhaps for his son Commodus to follow. He had groomed to follow in his father’s footsteps from an early age and the best minds available had been employed to see to his education. So, he was well-versed in morals, rhetoric, and good government. All that was required to be a good Emperor but this had been done at the expense of the more masculine pursuits and Commodus was to spend the rest of his life trying to compensate, and there were already signs that it may not be like father like son. He was it seemed lazy, negligent, arrogant and neurotic. Marcus Aurelius was concerned but still believed that these things could be educated out of him and in AD 177, following the death of Lucius Verus, he appointed Commodus his co-Emperor. He would accompany him on his military campaigns, he wanted to see how he would respond to the responsibility of power, and better to keep an eye on him - he was to be disappointed. Even so, the priority remained the creation of a dynasty and the avoidance of civil war.

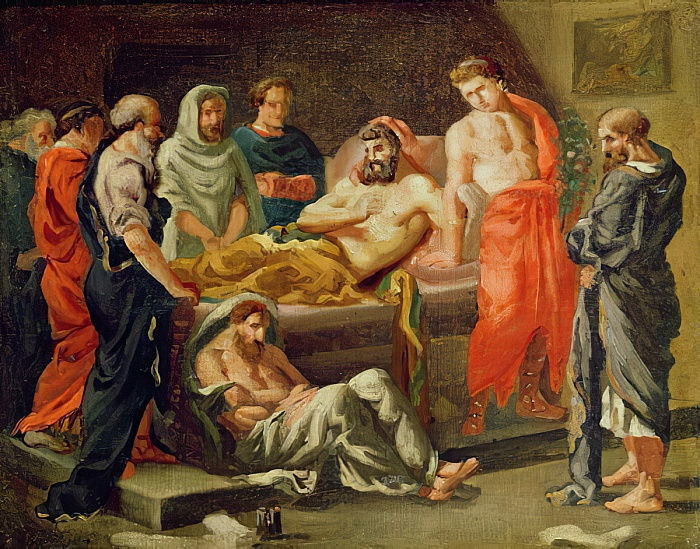

Marcus Aurelius who had never been a physically strong man was frequently ill and speculation as to his impending death was commonplace. Being on campaign with his army did not aid his health and it was on the Danubian frontier that he fell seriously ill. Taken to the city of Vindobona, or modern-day Vienna, on 17 March AD 180 he died.

The Emperor’s death was much lamented and greatly mourned for he had been a prudent, conscientious and just ruler who did not act arbitrarily outside of the law and respected the political institutions, customs, and traditions of the Empire he governed. But he had been no Republican a system he believed led to chaos and was determined to found a dynasty - the good dynasty. He had hoped the characteristics with which he was most closely associated would be passed on to his son.

Following his death there was the smooth transition of power that he had so desired and the nineteen-year-old Commodus would be the first biological son of an Emperor to inherit the Imperial Purple since Titus, the son of Vespasian, a hundred years before. Commodus who was still with the army swiftly concluded a peace treaty with the Danubian tribes so he could return to Rome as soon as possible and accept his nomination as Emperor, fearing perhaps a challenge though there was no other obvious candidate.

His reign did not start well however, He had little interest in addressing the Senate or listening to complaints about the many problems afflicting the city.

When they were critical of the rampant inflation he devalued the currency, prompting the historian Cassius Dio to remark: He turned Rome from a Kingdom of gold to one of rust and iron. All he seemed interested in was arranging a Triumph for himself which took place on 22 October to the rapturous scenes one would expect from a people receiving their new Emperor. Commodus mistakenly took this to be a genuine reflection of their love and affection for him, but the Romans just enjoyed a street party. Who needed the grey old men of the Senate he thought, when the people adore him so. It was an early sign of the megalomania that was to dominate his time in power.

It was evident from early on that he enjoyed the trappings of power but had no intention of running his Empire. This he would leave up to a series of unpopular and corrupt favourites from among his palace officials. So, the Government of the Empire, for the time being, lay in the hands of his Chamberlain, Saoterus.

In early AD 182, his sister Annia Lucilla, who had previously been married to Lucius Verus and had long harboured ambitions to be Empress, hatched a plot against him. She had been busily spreading the rumour that her brother was mentally unstable thereby providing a reason for replacing him. Now she would act.

She conspired with her cousins Marcus Quadratus Annianus and Cornificia Faustina to murder Commodus and place her husband Pompeianus Quintianus on the Throne. The assassination attempt was carried out by Lucilla's cousin Annius Claudius Quintianus, but he bungled it. As Commodus was walking through the corridors of the Palace, Quintianus, grasping a dagger, emerged from his place of hiding and shouted, "This is what the Senate has for you," but by doing so he had alerted the guards who overpowered him before he could do any harm.

The conspirators were arrested and executed. Meanwhile, Commodus had his sister Lucilla and Cornificia Faustina exiled to the Island of Capri. He later decided this wasn’t punishment enough and had then executed too.

Saoterus's great rival for power, Sextus Tigidus Perennis now took the opportunity to have him implicated in the plot and murdered without consulting the Emperor. Commodus took the death of Saoterus badly, it was rumoured that they had previously been lovers, but it was indicative of Commodus's indifference to government that instead of punishing the perpetrators they were simply elevated to replace his murdered friend.

Instead of rooting out those who may be his enemies Commodus decided to remove himself from Rome for his own safety, and he was happy to leave the levers of power in the hands of others whilst he indulged himself surrounded by flatterers and flunkeys.

Perennis now took Saoterus's place in running the Empire, and though he was ambitious and ruthless he was by no means the most corrupt of Commodus's officials. In fact, he was capable, efficient, and loyal to the Emperor but he was nevertheless to meet a similar fate to that he had enacted upon his predecessor. For he too had a rival for power, Cleander, Commodus's new Chamberlain, and the man that Perennis had ordered to murder Saoterus.

In October, AD 183, a detachment of soldiers recently returned from Britain, and under instruction from Cleander, approached Commodus to inform him that while they were stationed abroad, they had been contacted by Perennis seeking their support in an attempt by him to replace the Emperor with his son. Rather than initiate an inquiry, or even question Perennis regarding the matter, he simply shrugged his shoulders and ordered his immediate arrest and execution. Cleander was promoted in his place.

Unlike Perennis, Cleander was manifestly corrupt, and he used his new position to amass great wealth and accrue ever more power to himself. For example, he sold the Consulship of Rome 25 times in a single year when only two Consuls were expected to serve over a twelve-month period and these were meant to be elected posts. He also used his position of power to dispose of his enemies and those who were not willing to pay for their social and political advancement.

In the Spring of AD 190, food shortages in Rome caused an outbreak of rioting.

The man who oversaw grain supply Papirius Dionysius placed the blame for the shortages firmly at the feet of Cleander whom he claimed had been selling it on the black market. When the crowd watching the horse racing at the Circus Maximus rioted and began shouting for Cleander to be put to death, he responded by sending the Praetorian Guard to restore order. In turn, Pertinax, the City Prefect, dispatched the Vigiles Urbani, the city police, to oppose them with orders to protect the people. A showdown was looming but rather than commit to a fight the Praetorian Guard withdrew.

Cleander, with the Praetorian Guard having returned to barracks, was now forced to flee Rome and seek sanctuary at Commodus's villa at Laurentum. He begged for the Emperor's protection but encouraged by his mistress Marcia who had a deep loathing of Cleander, Commodus ordered his execution, along with that of his wife and children. A general bloodletting now followed as the Prefect of the Praetorian Guard Julius Julianus was executed, along with Papirius Dionysius and many others it was deemed convenient to be rid of.

The Rome that had known only peace under Pius Antoninus and prosperity under Marcus Aurelius was descending into chaos not known since before the days of Hadrian and if Commodus remained an absent Emperor it would continue.

As irksome as he found the day-to-day administration of his Empire he had little choice but to take personal charge. In AD 191, he returned to Rome. But stability and the rule of law did not return with him.

Commodus’s personal rule was as arbitrary and dictatorial as any of those who had previously served him. He rarely consulted with others and dismissed the Senate as a meaningless and irrelevant impediment to his ambitions. He merely issuing orders and expecting them to be carried out with immediate effect with any who hesitated punished accordingly.

The same year Commodus returned to Rome much of it was destroyed by fire and he seized on this opportunity to re-make the city in his own image. In early AD 192, he declared himself to be the new Romulus, the founder of Rome, and that everything associated with the Empire should bear his name - the Legions were now to be known as Commodianae, Alexandria in Egypt was renamed Commodianus, the Senate now had to be referred to as the Commodian Senate, and the Roman people were now Commodians.

He now added further names to his own until he had twelve and proceeded to name every month of the year after each one of them.

Commodus had by now totally rejected the austere and ascetic life his father had set aside for him, a life of books, of official documents, and endless meetings it wasn't for him. He’d rather indulge his passions and of these he had many.

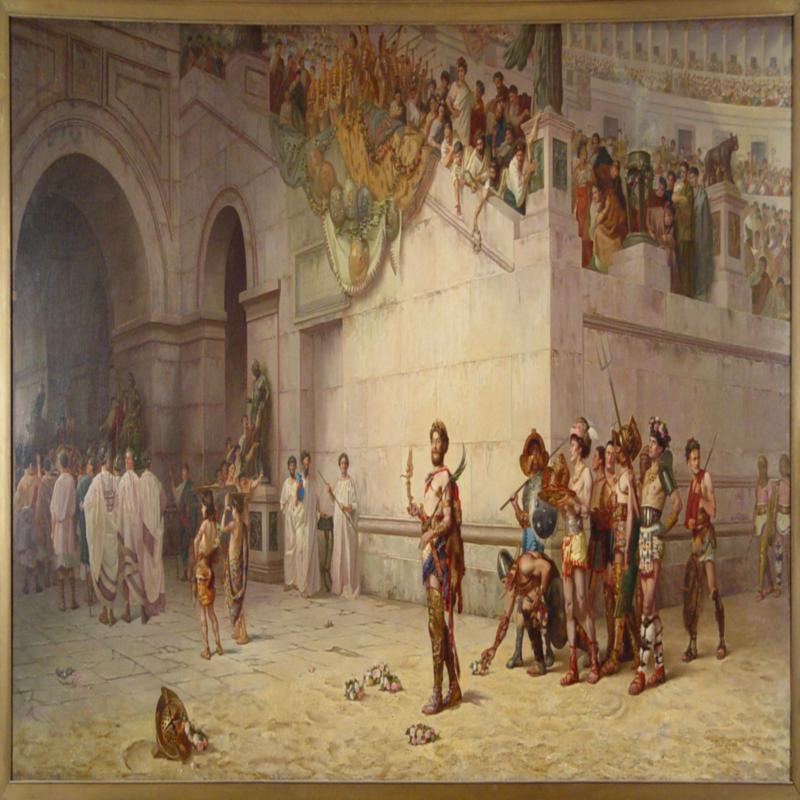

A handsome man with dark eyes, thick curly hair and athletic build his body was his one true love. He worked out relentlessly, often in public where people could witness his prowess with a sword and as an archer.

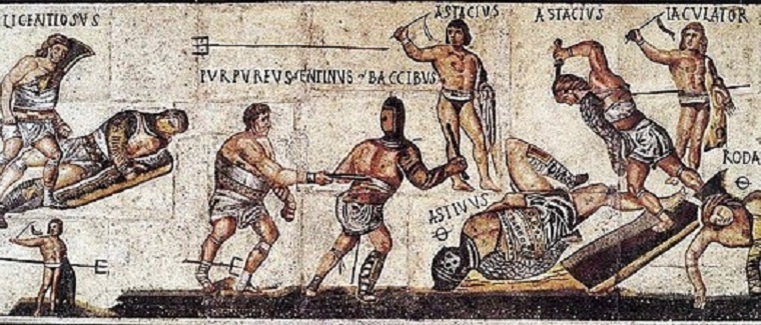

He enjoyed gladiatorial combat and performing in the arena, though his opponents were rarely gladiators, and if they were they were those who had been wounded in earlier combat and made incapable. On occasions amputees would be brought into the arena and tied together to be dispatched with a single blow in what he called his mercy killings.

He likewise slaughtered tethered and helpless animals on one occasion decapitating an ostrich before walking over to where members of the Senate were sitting and holding it up before them as if in warning. The crowd were not impressed by the killing of this harmless and exotic bird and booed loudly. Commodus glowered with fury, as he often would when the crowd jeered him. But the fee of 1 million sesterces he paid himself for every appearance he made in the arena, 735 in total, went someway to placating his wrath. Even if his public appearances were proving so expensive a new tax had to be levied to pay for them. But then he considered himself to be like Hercules and had statues erected of himself in his image.

He may have been an impressive physical specimen and an accomplished swordsman but unlike Hercules, he was perceived by the people of Rome to be a coward.

When he was not displaying his semi-naked torso to what he no doubt thought was an adoring public he indulged his love of sex and alcohol at his villa in Laurentum. There he kept a harem of 300 hundred young boys and girls who would perform naked for him at orgies that could go on for days.

This was the Commodus people knew and his long absences from Rome had fostered the ambitions of disloyal men who now resented the reassertion of his authority. Many also believed that his public performances in the arena had brought shame upon the office of Emperor and they worried that his evident bloodlust would soon see his sword turned on them. They could not feel safe as long as he remained Emperor.

Commodus's mistress Marcia, the Prefect of the Praetorian Guard Quintus Aemilius Laetus, and the new Chamberlain Electus, now plotted to murder Commodus and replace him as Emperor with the former Governor of Britannia Publius Helvetius Pertinax.

On 31 December AD 192, Commodus attended dinner as usual unaware that Marcia had dismissed his food tasters and liberally laced his meal with poison. Commodus ate heartily and drank to excess as usual but complaining of indigestion he vomited it all up again. For a time, he continued to drink copiously but after a while, and still seemingly ignorant that someone was trying to poison him, he declared that he was feeling unwell, made his excuses, and retired.

The plotters were in a panic about what to do and were all for fleeing while they still could, only Marcia kept a cool head. Learning that Commodus had decided to take a bath she summoned the famous wrestler Narcissus and ordered him to kill the Emperor. But if nothing else Commodus was physically strong and an attempt to drown him failed and it was only after a violent struggle that Narcissus was able to clasp his large hands around his neck and strangle him. Commodus was dead aged just 31, few people mourned his passing. His rule had been capricious, dictatorial, and cruel but the historian Cassius Dio, who lived at the time of Commodus, provides us with a more sympathetic view:

"He was not naturally wicked but, on the contrary, was as guileless as any man that ever lived. His great simplicity, however, together with his cowardice, made him the slave of his companions, and it was through them that he at first, out of ignorance, missed the better life and was then led into lustful and cruel habits, which soon became second nature."

Following the murder of Commodus Rome once again descended into chaos and it would now be the Praetorian Guard that decided who or who would not be Emperor. On 1 January AD 93, they chose Pertinax. After just 58 days when they did not receive the rewards, they had expected they murdered him. They now decided to auction the Imperial Throne to the highest bidder. On 28 March it was sold to the wealthy businessman, Didius Julianus.

The Senate only accepted him because they feared the wrath of the Praetorian Guard and very quickly made overtures to the Commander of the Pannonian Legions, Septimus Severus. He accepted the offer of the throne and marched upon Rome.

The Praetorian's were so debauched on the money they had received that they offered no resistance and just two months after buying himself an Empire, Didius Julianus was executed on the orders of the Senate.

So low had Rome fallen in a little over a decade.

Tagged as: Ancient & Medieval

Share this post: