Emperor Nero: Fiddling While Rome Burns

Posted on 3rd December 2021

Of all the Roman Emperor's none attracts and repels in equal measure more than Nero, the man who famously - "Fiddled while Rome burned."

He was a man who was in love with beauty but was capable of the greatest cruelty, a man who had his first wife executed, kicked his second pregnant wife to death, and ordered the murder of his own mother. Yet he could also weep over the plight of the poor and homeless; but then he believed that through the pursuit of beauty Rome could become a beacon of hope in an uncivilised world and he would bankrupt his own treasury to prove it. When the people objected to his excesses, he would brutally put to death an entire religious community to deflect the blame - he was never a man to engage in half measures.

He was born Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus in Antium near Rome on 15 December, AD 37. His father was Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus, a wealthy Senator, and a bad-tempered and often cruel man who displayed little interest in his children and died when Lucius was just three years old. His mother was Agrippina, the sister of the future Emperor Caligula.

Agrippina lived in the perilous environment of the Imperial Court, but she quickly learned to navigate its traps and pitfalls using her beauty and no doubt seductive charms to get her way and improve her standing. She could be ruthless but then had to be merely to survive. The lessons she learned early would serve her well later in life.

Caligula was notoriously fond of his sisters Drusilla, Livilla and Agrippina and is believed to have had an incestuous relationship with all of them. He also enjoyed watching them have sex and would force them do so in public so his friends could watch also. He was however particularly close to Drusilla whom he considered to be his de facto wife and when she died in AD 38 the increasingly paranoid Caligula became convinced that his other sisters had been jealous of their relationship and had been conspiring against him, so he had them both exiled to the Pontine Islands where they were forced to dive for sponges to make ends meet.

On 24 January AD 41, Caligula was assassinated after just four years in power. He was replaced on the Imperial Throne by his uncle Claudius who permitted his two nieces to return to Rome.

Before his death Caligula had forced Claudius to marry the 17-year- old Valeria Messalina a vain, deceitful and ambitious young woman thirty years his junior. It had been intended as a joke, but Claudius soon became besotted with his new wife. But then he was always a slave to his women.

Agrippina had returned to Rome her own ambitions undimmed, but she knew that as long as Messalina lived she would have to maintain a low-profile and so for a time she stayed away from the Imperial Court. She was determined to regain custody of her son Lucius who had been sent by Caligula to be raised by Messalina's mother, Aemilia Lepida. In this she succeeded but with her brother having auctioned off all her property she had returned to Rome penniless, so she was desperate to make a good marriage and made a shameless play for the future Emperor Galba but was humiliated when she was slapped in the face and given a public dressing down by Galba's mother-in-law. In the end it was Claudius who came to her rescue when he ordered the wealthy Senator Gaius Sallutius Crispus to divorce his wife and marry her.

In AD 47, Crispus suddenly died in mysterious circumstances, and it was rumoured that Agrippina had poisoned him, but no charges were ever brought and as his widow she inherited his estates and became a wealthy woman in her own right.

Messalina knew that Agrippina's son Lucius, as a descendant of Julius Caesar and the Divine Augustus was a rival to her own son Britannicus for the Imperial Throne. The two competing mothers were rivals for power, and they hated one another.

In AD 47, they both attended the Secular Games and the reception accorded to Agrippina and Lucius was greater than that for Messalina and her son Britannicus. It did not go unnoticed and later that night assassins were dispatched to murder Lucius as he slept. However, pulling back the bedclothes a snake emerged from beneath the sheets and believing it to be a bad omen the assassins fled without completing their task. The ten-year-old Lucius had had a lucky escape.

Meanwhile Messalina’s own behaviour was becoming increasingly erratic and when not cavorting with handsome young men of low birth she was competing with prostitutes to see who could satisfy the most clients. Now she had taken a lover of substance the leading Senator Gaius Silius. She had long considered her husband a fool and now decided that Gaius Silius should replace him as Emperor. Whilst he was away inspecting public works at Ostia, she married Silius and declared them to be the new Imperial couple.

She did not believe for a moment that anyone would oppose her, but she had misread the public mood. She was far more unpopular with the people than Claudius had ever been and there was no support for her coup. Upon his return, Claudius had Silius executed, and his wife placed under house arrest.

Despite begging for forgiveness and pleading that as the mother of his children she must be permitted to live, Claudius ordered that she take her own life. When she refused to do so a Praetorian Guard cut off her head. With the death of Messalina, Agrippina was free to pursue her own ambitions and she was determined now she had the opportunity, to marry her uncle despite his assertion that following this latest heart-breaking betrayal he would never marry again, but she would not take no for an answer and although she found him physically repulsive with his club foot, his stammer, his constant shaking, and his tendency to dribble she would seduce him. Sex with a monster was a small price to pay to secure the Imperial Throne for her son.

Despite it being an incestuous relationship and illegal under Roman law Claudius and Agrippina married in AD 48. She now worked tirelessly to persuade her husband to adopt Lucius as his son this despite being warned by a soothsayer that should her son ever inherit the Imperial Purple, he would end up by her killing her. She remained undaunted however, replying that: "Then let him kill me, as long as he becomes Emperor."

Claudius finally relented in AD 51 and even nominated Lucius as his successor, but only so long as Britannicus remained a minor. Lucius now changed his name to something more befitting his new status - Nero Claudius Tiberius Germanicus.

The young Nero, still only 13 years of age, was a boy described as either amiable or loathsome according to the hostility or otherwise of those who met him. Certainly, Claudius found him loathsome but then rarely was he not at his mother’s side while his artistic ways, the flowers in his hair and constant reciting of poetry could irritate to say the least.

In his book The Lives of the Twelve Caesar's, the historian Suetonius, described Nero as "about average height, his body marked with spots and malodorous, his hair light blond, his features regular rather than handsome, his eyes blue and somewhat weak, his neck over thick, his belly prominent, and his legs very slender. It was rumoured that as a young man he had an incestuous relationship with his mother. When they travelled together in a litter their activities within would be betrayed by the stains on his clothing."

Agrippina's domineering personality, her constant efforts to promote the interests of her son, and his own intense dislike of the boy saw Claudius once again look to Britannicus for the succession. This greatly concerned Agrippina for Britannicus would soon come of age - she needed to act. On the night of 13 October AD 54, Claudius attended dinner with his family as usual unaware that his wife intended it should be his last.

Knowing of his fondness for mushrooms Agrippina had employed a professional poisoner, a woman from Gaul named Locusta, to ensure that those he ate would be toxic. She had also given one of his food tasters the night off and had bribed the other to declare the mushrooms fit to eat having tasted one marked as being free from poison. Upon eating them Claudius quickly became ill as intended but unfortunately for Agrippina he vomited up the entire contents of his stomach.

A doctor was called to attend to the Emperor’s malady but he too had been bribed and suggested that Claudius tickle the back of his throat with a feather to rid it of any remaining toxins but had earlier soaked it in poison also. Soon Claudius began to choke and convulse and struggling to breathe slumped forward having lost consciousness. Agrippina ordered be carried from the room. He died soon after.

Nero, aware that murder had been committed on his behalf would later laud the health-giving properties of mushrooms often joking that Claudius, "had ceased to play the fool among mortals."

Following the death of her husband, Agrippina wasted no time in having her son declared Emperor, and the Senate endorsed it with hardly a murmur.

HHaving put her son on the Imperial Throne she was now determined to rule alongside him, and the first coins issued during his reign show the Emperor and his mother side-by-side, with Agrippina slightly in the foreground.

At her insistence she had been allowed to attend meetings of the Senate, though she was made to conceal herself behind a curtain and was not permitted to speak. However, when Nero met with the Armenian Ambassador, and she made to sit beside him she had overstepped the mark. In Ancient Rome it was unthinkable for a woman, of any rank, to intervene on a man's behalf when he was conducting business and she was only prevented from causing a scandal by Nero’s tutor Seneca who placed himself in her way.

He later warned Nero that his mother was ambitious and desired only to rule through him not with him, and a battle now commenced between Agrippina’s advisers and those of her son for influence over him.

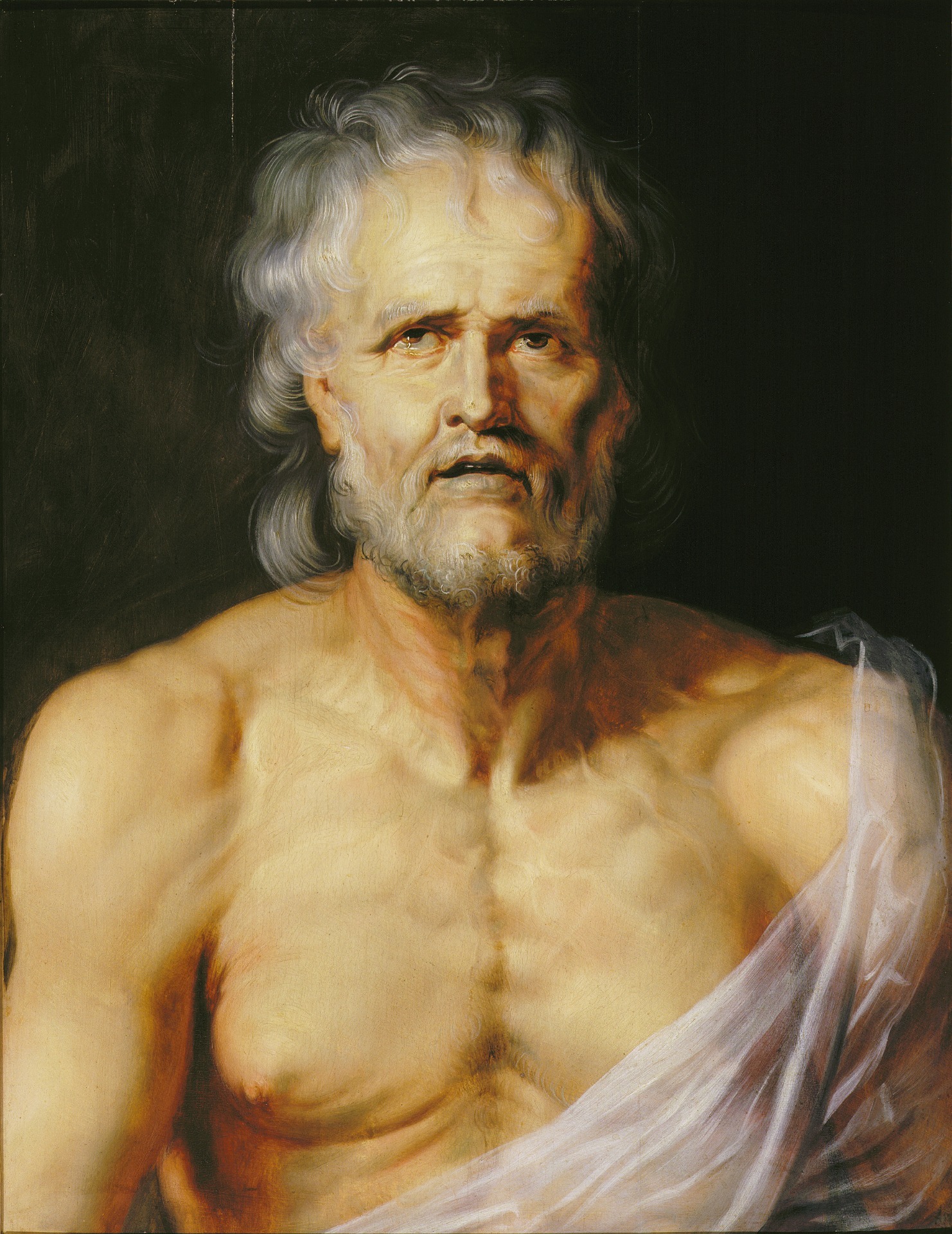

Dominated by his mother, though he was, Nero was also being advised by Rome's leading philosopher Seneca and the Commander of the Praetorian Guard Borrus. Seneca tried to instil in his young charge an understanding of justice and good government alongside a stern and unyielding morality.

Nero appeared keen to learn and was for a time considered a young man of great promise, perhaps even an Emperor of which Rome could be proud. But he soon began to tire of being told what he could and couldn't do and began to view his ever-present mother who nagged him incessantly as an encumbrance to his desires.

Before he became Emperor in AD 53, Nero had married Claudius's only daughter, the chaste and noble Octavia. It had been a political marriage and Nero rarely even saw let alone spoke to or slept with his wife having instead embarked upon an affair with a former slave, Claudia Acte. His mother, appalled at her son’s behaviour, demanded that he cease seeing her at once and return to his wife. Nero was inclined to do as his domineering mother told him but he was advised by Seneca and Borrus that his status as Emperor overrode any obligations he may have as a dutiful son and so he chose to ignore her. Agrippina fulminated against him but in vain and seeing that her influence over her son was slipping she began to turn her attentions to her step-son Britannicus.

Nero in the meantime dismissed Marcus Antonius Pallas from his service, an ex-slave who had risen to become Secretary to the Emperor Claudius he was a close adviser to and ex-lover of Agrippina and one of the few friends she still had within her son's inner circle. She was furious at his dismissal and threatened Nero that she would go to the Praetorian Guard, admit to being responsible for poisoning Claudius, expose him as a usurper, and declare that Britannicus was the only rightful heir to the throne.

Britannicus was thirteen years of age and Nero was aware of the threat he posed to his legitimacy and with his mother's imprecations still ringing in his ears he knew that he needed to act fast.

Like his mother before him he employed Locusta to concoct a poison that would kill Britannicus but when it was tested on a slave it failed to take effect and a frustrated and angry Nero threatened to have her executed if she did not come up with something, and very soon. She promised him that she had a potion that "would kill him quicker than a viper."

On the night of 11 February AD 55, the day before he was due to be formally declared an adult, Britannicus was invited to dine with Nero and his mother at the Imperial Palace.

Agrippina had been careful to ensure that all Britannicus's food was properly tasted but during the meal he complained that the wine served was too warm and requested some iced water be added. This was the opportunity the assassins had been waiting for and the poison was discreetly added to the water, and no sooner had he taken a sip than he began to violently convulse and foam at the mouth. Nero declared that he was having an epileptic fit and ordered that he be removed and taken to his bed. But he knew very well that he was already dead and while a visibly shaken Agrippina remained to pick nervously at her food, Britannicus's body was already being burned.

With the last rival to his throne removed, Nero now turned his attention to those in his life he considered an inconvenience, and none was more inconvenient than his mother.

Not long after the murder of Britannicus encouraged by Seneca and Borrus he forced her to live outside the Imperial Palace. In the absence of his mother Nero began to enjoy this unfettered assertion of his power and he now turned against his advisers and both Seneca and Borrus were put on trial for embezzlement. The brilliance of Seneca was to see them both cleared of the charges, but it was an indication that the young Emperor was becoming increasingly difficult to control and though they continued to advise him their influence had been greatly reduced.

In AD 58, Nero fell in love with the beautiful, vain, mercurial and bisexual Poppaea Sabina, an exotic dancer of low-birth and even lower- morals. He wanted to marry her but knew his mother would never agree to him divorcing Octavia.

Considered chaste and beyond reproach Octavia was not only the daughter of the old Emperor but was seen as the very epitome of Roman Womanhood and was popular with the people but as far as Nero was concerned, she was dull and mocked his artistic aspirations - he could not bear to be near her. He wanted rid of her but first he had to be rid of his mother.

Nero had already tried to murder her more than once and Agrippina had taken to imbibing antidotes to poison before she ate. Unable to kill her by his preferred method he'd had a mechanical lead ceiling constructed designed to crush her to death as she slept, but it had failed to work. He was nothing if not creative in his murderous intent.

In AD 57, Nero forced his mother to live at her a lakeside villa in Misenum. There he would send people to stand outside and harangue her throughout the night, to interrupt her sleep and abuse her whenever she emerged in public. He wanted to make her life a misery just as she had made his.

On the night of 23 March, AD 59, Nero invited his mother to dine with him at the Imperial Palace. As usual she berated him for his behaviour and his treatment of her, and reminded him, as she always did, that he was only Emperor because of her.

Nero held his tongue because he believed this would be the last time he would ever have to endure her curses and insults that he expected never again to cower in her presence for he'd had a special boat designed for her return trip that would break apart mid-journey and drown her.

Agrippina was lying on a high-backed sofa with her friend Acceronia Polla when the roof of the boat collapsed. The height of the sofa saved them both from death though a servant present was killed. There was little time for either of them to react for almost immediately the hull of the boat broke away and they were both thrown into the water.

Acceronia Polla was a poor swimmer, but Agrippina told her that if she cried out that she was the Emperor's mother then those on the accompanying boat would save her first. As she did so Agrippina swam for shore. The guards on the accompanying boat however believing Aceronia Polla was Agrippina instead of pulling her on board beat her in the water with poles and clubs until she drowned. In the meantime, an exhausted and bedraggled Agrippina made it to shore her time diving for sponges during her exile having served her well.

Upon hearing that his mother had survived his latest attempt to murder her, Nero abandoned all pretence of making it appear an accident and ordered Borrus to go to Misenum and kill her, but Borrus refused to be implicated in matricide. So, instead he got a contingent of Naval Officers to carry out the deed.

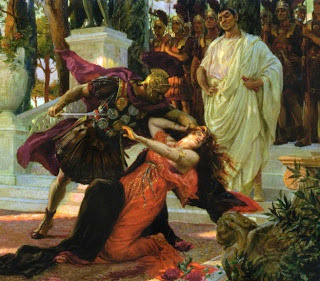

Agrippina was discovered lying on her bed recovering from her ordeal. At first she chastised the Officers for disturbing her at such a late hour but then realising why they were there, she tried to rise from her bed but was struck over the head before she could do so and screamed that no son would order the murder of his own mother and that they had been given incorrect orders. If they did not leave immediately, they would pay dearly for their mistake. But they took no notice and instead drew their swords to finish her off. Realising it was the end Agrippina threw off the bedclothes and pointing to her womb said, "Strike Here."

Earlier that day Nero had forced his aunt Domitia to commit suicide and in time he would have all his relatives executed. He did not want rivals to his throne and the maintenance of the dynasty would be down to him alone, just as he wished.

Delighted to hear the news that his mother was dead Nero remarked, "At last I can live like a man." He also inspected Agrippina’s corpse before her funeral and kissing her on her forehead said: "I hadn't realised how beautiful my mother was."

He appeared at ease with what he had done but at the funeral itself he looked pale and scared and was unable to give the eulogy. Indeed, for the rest of his life he was tormented by the presence of his mother in his dreams and believed that he was haunted by her ghost even taking potions meant to make her go away, employing magicians to chant spells, and priests to enact exorcisms. Yet he also took as one of his concubines a woman whom he thought identical in looks and appearance to his mother.

Even though, he would pronounce her death a tragic accident, hold lavish games in her honour, declare a public holiday with free food and wine for the people and praise her in the Senate House, everyone knew the truth.

Nero now brought Poppaea to the Imperial Palace as his mistress where she soon became hated by those officials who served the Emperor as overbearing, arrogant and incredibly vain. It was said of her: "Poppaea had every asset but goodness. She seemed respectable but her life was depraved. She would half veil her face to stimulate curiosity. To her married men and bachelors were all the same." She would bathe in asses, milk for much of the day and maintained a herd of 500 donkeys specifically for that purpose. At night she would have her hair tended to and her nails painted, and she told Nero that she hoped to die before her beauty faded. She also told Nero that merely being his mistress was not enough and that she wanted to be his wife and Empress of Rome.

In the Spring of AD 62, Sextus Afrianus Borrus died and in the wake of his death Seneca, who had tired of Nero's behaviour and now believed that without Borrus he could no longer influence the Emperor, requested to be allowed to stand down from public affairs. His request was denied. He may have thought that he could do without Nero, but Nero could still not do without him.

With Borrus gone Nero now felt able to move against his wife Octavia accusing her of having affairs behind his back and asked the new Prefect of the Praetorian Guard, Gaius Sophonius Tigellinus, to investigate. He interrogated her servants as to her nocturnal activities but when he suggested to one of them that she was a whore he was told: “My mistresses, private parts are cleaner than your mouth."

All of her servants remained loyal, and he was unable to unearth the kind of salacious evidence against his wife that the Emperor had hoped for and Nero's attempt to besmirch the reputation of Octavia went down badly with the Roman people. She was much admired for her modesty and nobility in stark contrast to the always painted, over-dressed, and sexually wanton Poppaea. Nevertheless, in the early summer of AD 62, he had Octavia exiled to the Island of Pandateria. He then divorced her on the grounds of her infertility, an accusation difficult to prove given his refusal to have sex with her. But this was not enough for Poppaea who bristled at the people’s demand that Octavia be permitted to return and so on 9 June AD 62, Nero had her murdered.

He could now begin to enjoy his life and unlike Borrus before him, Tigellinus was only too happy to encourage him in his excesses and would even accompany him on his late-night escapades. No Emperor had ever before got so close to his people, quite literally, and so mirrored their behaviour in the way Nero did. His excesses were manifest and even for the violent and amoral streets of Rome he could be said to have set a bad example.

As the historian Tacitus explains:

"After it was dark, he used to enter the taverns disguised in a cap or wig, and ramble about the streets in sport, which was not void of mischief. He used to beat those coming home from supper, and if they made any resistance, would wound them and throw them into the common sewer. He broke open and robbed shops, establishing an auction in his home for the sale of the booty.

He often supped in public and was waited upon at table by the common prostitutes of the town and Syrian strumpets and glee-girls. Often he went as far down the River Tiber as Ostia where booths furnished as brothels and eating-houses were erected along the shore, before which stood matrons who like bawds and hostesses, allured him to land."

But most of all Nero wanted to perform and he learned to play the lyre, wrote poetry in both Latin and Greek, and undertook exercises to improve his singing voice. His mother had lambasted him for his love of all things Greek and his absurd artistic pretensions, but Poppaea encouraged him saying that he was among the greatest artists who had ever lived.

In July AD 64, a great fire swept through Rome. It had ignited in the Circus Maximus and in no time at all had become a raging conflagration that lit up the night sky for miles around.

The historian Cassius Dio describes how Nero climbed onto the roof of the Imperial Palace and sang The Capture of Troy as the flames consumed his city, but the truth was that he was in Antium at the time and rushed back to Rome as soon as he heard the news.

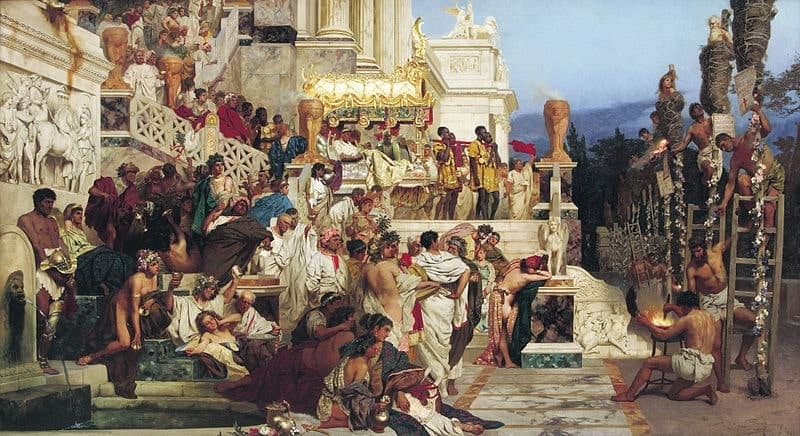

Nero tried to combat the disaster as best he could and took personal charge of the fire fighting. He also made available the grounds of the Imperial Palace and nearby gardens to shelter the people providing them with food and water. Yet and despite his best efforts much of Rome was burned to the ground and though he wept over the distress of the people and the destruction of the city the prospect of rebuilding it also excited him. He would recreate it in his own image, he said. He would make it beautiful.

A vast area between the Palatine and Equiline Hills had succumbed utterly to the flames, and it was on this land that he decided to build the Domus Aurea, his Golden House. It was to be a vast complex with its own zoo, pleasure gardens and with an enormous artificial lake as its centrepiece: "Its vestibule was large enough to contain a colossal statue of the Emperor, one hundred and twenty feet high, and it was so extensive that it had a triple colonnade a mile long. There was a pond to, like a sea, surrounded with buildings to represent cities, besides tracts of country, varied by tilled fields, vineyards, pastures, and woods with great numbers of wild and domestic animals. In the rest of the house all parts were overlaid with gold and adorned with gems and mother-of-pearl. There were dining rooms with fretted ceils of ivory, whose panels could turn and shower down flowers and were fitted with pipes for sprinkling the guests with perfumes. The main banquet hall was circular and constantly revolved day and night like the heavens."

Upon its completion a delighted Nero would remark: "At last I can live as a human being should."

But to most people it became seen as a ruinously expensive vanity project, and despite Nero having spent vast amounts of his own money providing housing for those who had lost everything the rumour soon began to spread that he had started the fire deliberately just so that he could build his Golden House, a symbol to his own magnificence carved in stone.

His project to re-make Rome in his own image soon became his obsession and he was determined that it should be completed despite the fact the treasury had been drained to pay for it. As a result, he raised taxes to punitive levels throughout the Empire, though always conscious of his popularity with the people he endeavoured not to raise the level of taxation for the ordinary Roman citizen.

It was the nobility, the rich, merchants and the more prosperous tradesmen who would pay and when this proved inadequate, he exiled some and appropriated their property. Still, it wasn't enough and increasingly frustrated he faced the prospect of having to abandon the building work which would for him be a personal humiliation.

Whenever a public sacrifice was made, a donation was provided to the Temple of the God concerned. It was this that secured the protection of the city and to even think of raiding the Temple vaults was an abomination. Even so, despite it being sacrilege to do so on the advice of Tigellinus, he ordered them ransacked. It was this one event, more than anything that had gone before which at last turned his old mentor Seneca against him.

Meanwhile, the rumour persisted that he had started the fire deliberately. The people had also not forgotten the murder of Octavia and the rape of the Temple. The pressure on Nero was mounting and he needed a scapegoat upon whom he could deflect the blame. Finally, he alighted upon a small religious sect - the Christians.

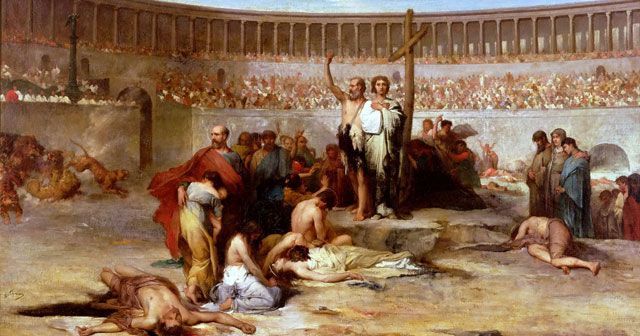

They were already unpopular for denying all other Gods in favour of their One True God and now he ordered a round-up of known Christians in the city all of whom were to be executed. As Tacitus explains:

"Nero fastened the guilt and inflicted the most exquisite tortures on a class hated for their abominations, called Christians. Accordingly, an arrest was made of all who pleaded guilty, then, upon their information, an immense multitude was convicted, not so much of the crime of firing the city, as of their hatred against all mankind. Mockery of all sorts was added to their deaths. Covered with the skins of beasts they were torn by dogs and nailed to crosses, or were doomed to the flames and burnt to serve as a nightly illumination, when daylight had expired."

Nero was determined that the people should witness their punishment and he had many fed to the lions in the Arena for their entertainment. He also illuminated the exterior of the Imperial Palace with Christians nailed to crosses, burned to serve as lamps by night:

"Nero offered his gardens for the spectacle, as if he was exhibiting a show in the circus, while he mingled with the people in the dress of a charioteer."

The persecution of the Christians failed to deflect criticism away from Nero for they were palpably not to blame for the fire that had consumed so much of the city, and their hideous deaths rather than celebrated had elicited a degree of sympathy from the Roman people that had previously been unimaginable. It was the first instance of mass Christian martyrdom, and it only brought them even more followers.

Administering his Empire had always bored Nero and he was happy to let his advisors do the work and permitted the Senate to pass laws that he would then merely endorse. One such law held that all the slaves in a household should be punished for any crime or misdemeanour committed by any one of them and its passage led to days of violent rioting that was only ended when he had 400 slaves publicly executed.

His primary concern was always the love of the people and he remained popular with the man on the street but while he indulged himself in Rome his Empire descended into chaos.

A long and costly war with Parthia over the territory of Armenia was concluded with a treaty that left a Parthian Prince in control of the disputed region which increased his popularity in his Eastern Empire but was viewed as a humiliating defeat in Rome. Meanwhile, in AD 62, Boudicca, Queen of the Iceni Tribe, led a rebellion that came perilously close to losing Rome the Island of Britannia. Four years later in AD 66 the province of Judea rose in revolt.

Nero, who often turned his face from bad news, wanted such problems resolved without him and he delegated power to others to do so, but some problems remained simply too close to home. In AD 65, the Senator Gaius Calpurnius Piso conspired with other leading politicians and Army Officers to overthrow Nero and return Rome to a Republic.

The freedman Milichus, overhearing the conspirators discussing the plot reported it to Nero's secretary Epaphrodites, and Nero was able to crush the revolt before it gathered momentum. More than 50 Senators and Army Officers were put to death among them the famous poet Lucan and Nero's old mentor and friend Seneca, who was forced to commit suicide.

One of those Army Officers to be executed, Flavius, was questioned by Nero personally as to why he betrayed him, he replied: "Because I hated you, I was as loyal as any of your soldiers as long as you deserved affection. I began to hate you when you murdered your mother and wife, and became actor, charioteer, and fire-starter."

With the crushing of the Pisonian Conspiracy and the purging of his enemies, Nero felt once more secure upon his throne particularly as, on the advice of Tigellinus, he had decided to reintroduce the Treason Trials last seen during the reign of Tiberius. With spies everywhere and any man of substance in Rome terrified of being denounced, Nero could now spend his days in private performance or at the Chariot Races where he was an enthusiastic supporter of the Green Team.

One night he returned home late from the Races to be greeted by Poppaea who chastised him for missing dinner. In a rage, Nero knocked her to the ground and stamped repeatedly on her heavily pregnant belly until both she and her unborn child were dead. Nero was distraught at what he had done and wept copiously for his lost love and the child he would never see in his grief ordering that Poppaea's body should not be cremated as was the custom but instead be stuffed with spices and embalmed.

For a time, he had Poppea's corpse sat behind him when he addressed the Senate before having it put on display in the Mausoleum of Augustus. Later he had a pretty young male slave named Sporus castrated and forced him to dress like Poppaea and affect her mannerisms. He did, it was said, use him in every way as a wife, and he was made to answer to the name of Poppaea.

He had also found for himself a new and entertaining distraction. He would be let out of a den in the arena covered with the skin of a wild beast and then assail with violence the private parts of men and women bound to stakes. Once he had vented his furious passions, he would collapse into the arms of his freedman Doryphorus, who would relieve him of the lust that had infected his body, and to whom he was married in the same way as he was to Sporus. Little wonder, it was said that there was no part of his body that remained undefiled.

Nero was eager to return to his first love, the theatre and shaved off his beard, which he had worn in the Greek style, and grew his hair long which he adorned with ribbons. He took his art very seriously as Suetonius tells us: "He neglected none of the exercises which singers were in the habit of following, to preserve or strengthen their voices. For he used to lie upon his back and hold a leaden plate on to his chest, purge himself by vomiting, and deny himself fruits and foods injurious to the voice."

His voice however remained weak and somewhat husky.

He had been performing in private for friends and invited guests for some time and no one was permitted to leave the auditorium during one of his recitals no matter how pressing the reason, and his recitals could be interminable, so interminable that women were known to give birth, and men so bored of listening that they dropped down off the wall at the rear because the gates had been barred, or feigned death and were carried off for burial.

Nero's first ever public performance had taken place at the auditorium in Neapolis or Naples in AD 64. It had been well-received by the audience as you might imagine but it was considered scandalous among the political elite in Rome - an Emperor performing for the public like a common prostitute! As the historian Cassius Dio remarked: "In putting on the mask of an actor he threw off the dignity of his sovereignty."

Nero couldn't care less what they thought, as far as he was concerned, he was the finest artist the world had ever known and to deprive the people of his talents would be a crime against the Gods. So, the following year he sang at the Second Quinquennial Neronia, a huge festival of the performing arts held in the Greek style that he had earlier introduced.

In late AD 65, Nero took his talents on the road with a tour of Greece, leaving Rome in charge of his freedman, Helius.

While Rome continued its slow descent into chaos in his absence, Nero was having the time of his life. He sang, played the lyre, and recited poetry before thousands of people. He entered competitions and much to the disgust of many in Rome his name appeared in the programme of events along with the other contestants.

Acting, or any other theatrical performance was considered among the lowest of professions and entertainers had a status barely above that of a slave. There were murmurs in Rome that their Emperor had gone insane but no one was willing to go public with their views. In AD 67, he was invited to participate in the Olympic Games. He needed little persuasion and entered the Ten Horse Chariot Race which he won despite falling from his chariot and failing to finish.

Surrounded by luxury and seduced by sweet words of flattery Nero had never been happier and he believed himself exalted among men but discontent with his rule was growing in Rome.

In his absence, Tigellinus had intensified the clampdown on dissent and speeded up the rate of the Treason Trials. In late AD 67 he accused Rome's ablest General, Gnaeus Domitius Corbulo of plotting against the Emperor. Nero summoned him to Greece where he forced him to commit suicide. The General had been very popular and many leading Officers in the army now feared that if Nero could dispose of Corbulo in such an arbitrary way then none of them were safe.

Public disturbances were also becoming a familiar feature of daily life in Rome exacerbated by a food shortage that was threatening the city with starvation.

The freedman Helius was unable to cope but his increasingly frantic requests for the Emperor to return were ignored. Eventually, he was forced to travel to Greece and plead with the Emperor in person. Under pressure Nero relented and by January AD 69, he was back in Rome. He was greeted upon his arrival with much splendour and lavish celebrations as he proudly showed off the 1,108 victory garlands he had acquired while he was in Greece and accepted with good grace the many plaudits and gifts that came his way. But the truth was that many people had already begun to look elsewhere for an Emperor.

Earlier in March AD 68, Gaius Julius Vindex, the Governor of Gaul, had rebelled against Nero and had appealed to Servius Sulpicius Galba, the much respected 71- year- old military veteran and Governor of Spain for support. He even suggested that he should become Emperor. Galba remained silent on the matter and Vindex was later defeated at the Battle of Vesontio by the Rhine Legions led by Lucius Virginius Rufus.

It seemed that the rebellion had been nipped in the bud, but it had served to nurture in the public imagination the possibility of Galba as Emperor. Nero was aware of this and suspecting Galba of plotting against him he declared him a public enemy. This was to prove a mistake for it placed the previously ambivalent Galba in direct opposition to him and the Senate which had been lacking leadership now had someone to turn to.

Tegillinus, who seeing the tide was turning had already deserted Nero and was replaced as Prefect of the Praetorian Guard by Gaius Nymphidius Sabinus, who repaid the Emperor by now pledging his support to Galba. Nero, who still retained the loyalty of the Rhine Legions, may well have been able to overcome the crisis but instead he panicked.

Waking one morning in the Imperial Palace to find his guards and many of his servants gone he fled Rome for nearby Ostia where he toyed with the idea of taking ship to the Eastern Provinces, but he was unable to commandeer one. He returned sheepishly to Rome confused and unable to think of a course of action.

He could appeal directly to the people for their support, after all despite their differences he had kept their taxes low, and they had always had affection for their colourful Emperor who never failed to provide them with such rich entertainment. Or he could throw himself upon the mercy of General Galba, a man to whom he had always shown the utmost respect. But the truth was he simply did not know what to do.

Back at the Imperial Palace an exhausted Nero fell into a deep sleep. When he awoke around midnight, he found the Palace once again virtually deserted except for a small number of his personal servants. He cried out for a guard, a gladiator, someone to protect him but none came. In despair he wailed: "Have I neither friend nor foe?" He proceeded to visit the slave quarters but was to find them deserted too. He had little option now but to flee, but to where?

A loyal freedman came to his rescue and offered him his villa some four miles outside of Rome and so he fled in disguise with just four loyal companions to accompany him. Not long after his arrival at the villa a courier appeared to inform him that the Senate had declared him a public enemy. It was now the duty of every Roman citizen to either kill him or do him harm.

In despair, Nero ordered that a grave be dug for him, he would commit suicide, he said, the noblest exit known to a Roman outside of death in battle. He would then, at least maintain his honour and die with dignity. But he did not have the courage to do it and with his hand trembling so violently that he was unable to hold the knife he asked his servant to stab him in the heart, where, he said, so many others had stabbed him before.

He did as his master had instructed, and the Emperor Nero, the most powerful man in the world on the run and in hiding, bemoaning all those who blind to his genius had betrayed him, died a painful and lingering death. His last words, "What an artist I die." He was 31 years of age.

Tagged as: Ancient & Medieval

Share this post: