Empress Theodora

Posted on 16th April 2021

She lived to wear the Imperial Purple and become arguably the most powerful woman ever to emerge from the Roman Empire East or West; but she wasn’t born to such exalted status. Indeed, she was of no background whatsoever, neither was she from Rome nor even Constantinople but from the remote village of Paphlagloria in Cyprus. Her mother, also Theodora, was an entertainer well vested in the art of seduction, a skill she passed on to her daughter. Her father, Acacius, was a bear trainer working for the Green Faction at the Hippodrome in Constantinople.

A vast enclosed building that stood adjacent to the Imperial Palace the Hippodrome was the entertainment centre of Constantinople and the venue for the hugely popular chariot races, but much like the Colosseum in Rome it was never just about sport it was a place for deal making and political intrigue; an often seething cauldron of social discontent, a place of violence and intimidation where the great and the good needed to be seen but feared to tread and where religious disputes were settled in the arena and not the cloister. It was about who ruled, and the Factions who dominated could make and break regimes.

The Circus Factions – Blue, Green, Red and White – operated as rival gangs which were little better than criminal enterprises running prostitution rings and extortion rackets within their own spheres of influence. The rivalry between the Factions was fierce and often political and it was into this world of violence and corruption that Theodora was raised.

Theodora, whose father died when she was aged three, was invested into the life of the Factions early when her mother now destitute needing the support of at least one or other of the Factions to survive brought her and her two sisters into the Hippodrome on the day of the chariot races adorned in blue ribbons and wearing blue garlands and dedicated her life and those of her daughters to the Blue Faction. Though she had previously been a Green she knew that the Blue Faction represented the lower class and was by far the most numerous and powerful. It was to prove an astute move.

While still just a girl Theodora was made to work in a brothel to pay her way and she was obviously very good at what she did for she soon moved from servicing the sexual requirements of low-class clients for pennies most of which was taken by the pimp that had been provided by the Faction to the more lucrative role of circus entertainer as a dancer and mime artist. Here she provided sexually explicit shows for the social elite. Particularly popular was her notoriously lascivious portrayal of Leda and the Swan where she would be stripped naked, lie on her back, and have barley sprinkled over her breasts and nether regions to be pecked at by geese. She soon became a star attraction for the great and good of Constantinople and it was during a performance of Leda and the Swan that she met Antonia, the wife of Bellisarius who would go onto become the Empire’s leading General and the future Emperor Justinian’s right-hand man. It was a valuable contact, and they were to remain lifelong friends.

At the age of sixteen Theodora travelled to Libya as the mistress of its new Governor Hecebolus. If she believed this offered the opportunity for a better life, then she was to be bitterly disappointed for Hecebolus treated her like the whore he obviously thought she was. After she became pregnant, he lost all interest in her. Abused, ill-treated and abandoned in AD 522 along with her young daughter she returned to Constantinople. She had no desire to return to her previous way of life and tried to make a living as a wool spinner but it was hard work and she barely made enough to maintain herself let alone her child.

The lure of the Circus Factions and the rewards on offer were to prove too greater a temptation and she was soon back to doing what she did best, seducing men for money.

The future Emperor Justinian, like Theodora was of humble origin. He had been born Petrus Sabbiatus in the town of Traeserium in Thrace, or modern-day Serbia in AD 483. He was of peasant stock but the fact that he spoke Latin, indeed he was to be the last Byzantine Emperor to do so, indicates that his family had known better times. It appeared that his life was destined to be one of poverty and back-breaking toil in the fields but his mother, Virgiliana, was the sister of Justin the Commander of the Excubitors, or Imperial Guard in Constantinople. She was unable to cope raising her children on her own and appealed to her brother to allow the young Petrus to visit and remain with his uncle in the city. Justin, who had no children of his own, was happy to oblige.

Justin was to provide for the boy’s education and secure him a commission in the Imperial Guard. Petrus who in return took his uncle’s name calling himself Justinian was to prove a capable, energetic and ambitious young man. Justin was impressed by his nephew, and he was promoted rapidly through the ranks of the Guard.

In AD 518, the Emperor Anastasius died without an heir and the hard-working and ever loyal Justin became the obvious choice to succeed him. Suddenly and unexpectedly, Justinian, the rough peasant boy from Thrace was in-line to the throne of the Byzantine Empire.

As the nephew of the Emperor, it was only proper that Flavius Justinianus, as he was now known be provided with the title and honours that fitted his new exalted status, and he was appointed a Senator. He was described at this time as being: “Short in stature, with a good chest, fair skinned, curly haired, round faced and handsome.” He was friendly, amiable, and so it seems popular. It wasn’t to last.

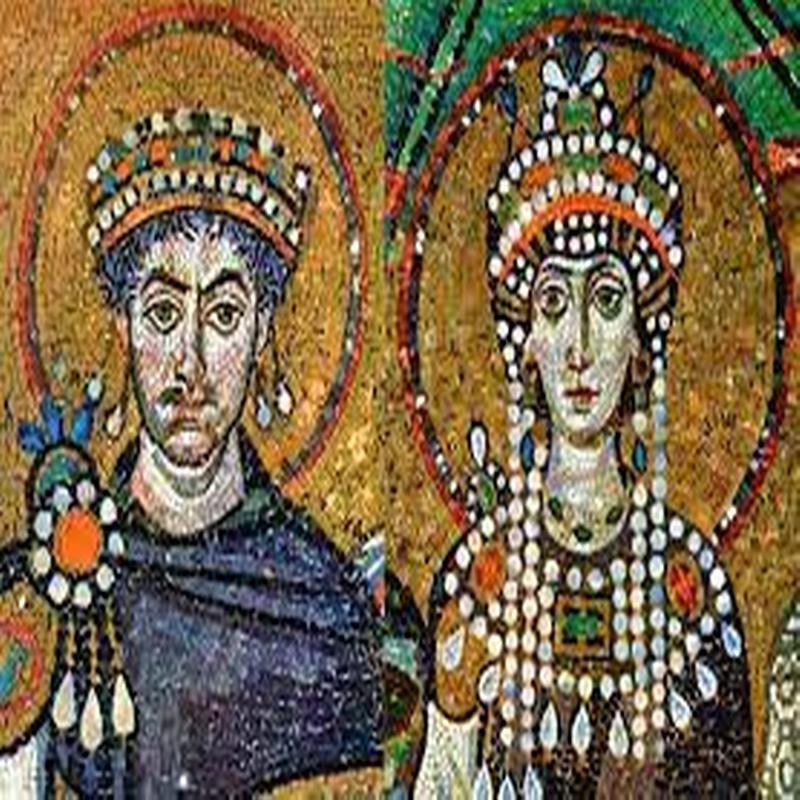

It was around this time that he met Theodora though as a supporter of the Blue Faction he would almost certainly have already been aware of her. He fell hopelessly in love with this beautiful young woman so well-schooled in the art of seduction, highly intelligent, witty, straight talking and who could swear with the best of men all traits considered unseemly in a woman, but which appealed greatly to the equally roughly hewn Justinian. As far as he was concerned it was love at first sight.

Justinian was determined to make Theodora his wife, but it was illegal for a Senator to marry beneath himself and a circus entertainer was about as low as it could possibly get so he petitioned his uncle Justin for a change in the law. The Empress Euphemia however despite being personally fond of Justinian and disinclined to deny him anything would not countenance any such thing and it wasn’t until after her death in AD 525 that he again approached Justin who had always been more malleable on the issue. He agreed to his nephew’s request and had the law changed.

Justinian and Theodora were wed soon after but there was little acclaim or public rejoicing. The elite of Constantinople were appalled believing he had brought the aristocracy into disrepute by marrying someone who was little better than a common street prostitute. They were also offended that he had rejected many more suitable candidates from among themselves.

On 1 August AD 527, the elderly Emperor Justin died. In his declining years he had been displaying the signs of senility and had become increasingly reliant upon his nephew Justinian to run the Empire for him. He was the obvious choice to replace him.

Upon becoming Emperor, it soon became apparent that he was no longer the amiable and approachable young man that he had once been but had become distant and aloof. He had always been deeply conscious of his humble background and lowly status at Court. Now both he, and in particular Theodora, became sticklers for Court ceremony. Government officials and even the most venerable of Senators were made to prostrate themselves in the Imperial couple’s presence.

If Justinian’s need to compensate for his poor Thracian background by forcing those who considered themselves his better into petty acts of obeisance wasn’t humiliation enough, he now began to interfere in areas of governance that had previously been the fiefdom of others. But it was to be upon his wife that the greatest opprobrium would fall. Procopius in his Secret History wrote of Theodora:

“Often she would attend a dinner party with ten young men or more all at the peak of their physical powers and with fornication as their chief object in life; and she would remain with her fellow diners all night long reducing them to state of physical exhaustion.” He went onto to describe how: to her bodily needs she devoted quite unnecessary attention. She was always in a hurry to get into her bath, and was very reluctant to get out of it.”

The rumours of her insatiable sexual appetite and love of luxury were to persist throughout her life. It was said that Justinian was aware of her behaviour but turned a blind eye to it, that he was willing to indulge her in almost anything. Indeed, many people believed that it was Theodora who was running the Empire. It wasn’t true but her influence was undoubted and in time Justinian was to take the unprecedented step of making her co-Regent and they were to go on to form one of the most remarkable working partnerships in history.

Many of the acts of Justinian’s reign were taken at the prompting of Theodora at a time when a woman was expected to be decorous and obedient and little else. To many people this was either a sign of weakness and unfitness to rule on his part or that she was a witch and had cast a spell over him. The preference was to believe the latter and the hatred felt towards her among the elite was widespread and palpable. Justinian did little to deflect the criticism for unlike so many of his predecessors he was no tyrant and was already distracted by his obsession with the law.

One of the first acts of his reign was to begin the codification of Roman law and his Corpus Junus Civilis still forms the basis of Civil Law in many European States today. His Codex Justinianus was issued on 7 April AD 529. It was not well received with many Magistrates believing that it infringed upon their prerogatives. Whilst Justinian focussed on the law, Theodora turned her attention to civil and religious matters.

Both Justinian and Theodora were Christians, as were many of the political and social elite, but many of the common people still worshipped the old Gods. Under pressure from Theodora, Justinian legislated against pagan belief. Those civil servants who held onto their pagan beliefs were removed from their posts. Those who publicly converted to Christianity but continued to worship the old religion in private were liable to execution for heresy. Theodora was also instrumental in forcing through anti-Jewish legislation and many of Constantinople’s Synagogues were torn down.

Theodora was also responsible for encouraging a moral crackdown. Homosexuality was publicly condemned; brothels were closed down and those caught committing a homosexual act were publicly castrated encouraging vigilantes to roam the streets inflicting their own form of rough justice. Gambling was also banned and the punishment for doing so was to have your hands severed. Both Justinian and Theodora were playing a dangerous game for both prostitution and gambling provided a substantial source of income for the Factions and in curtailing their activities the Imperial couple were inviting their wrath.

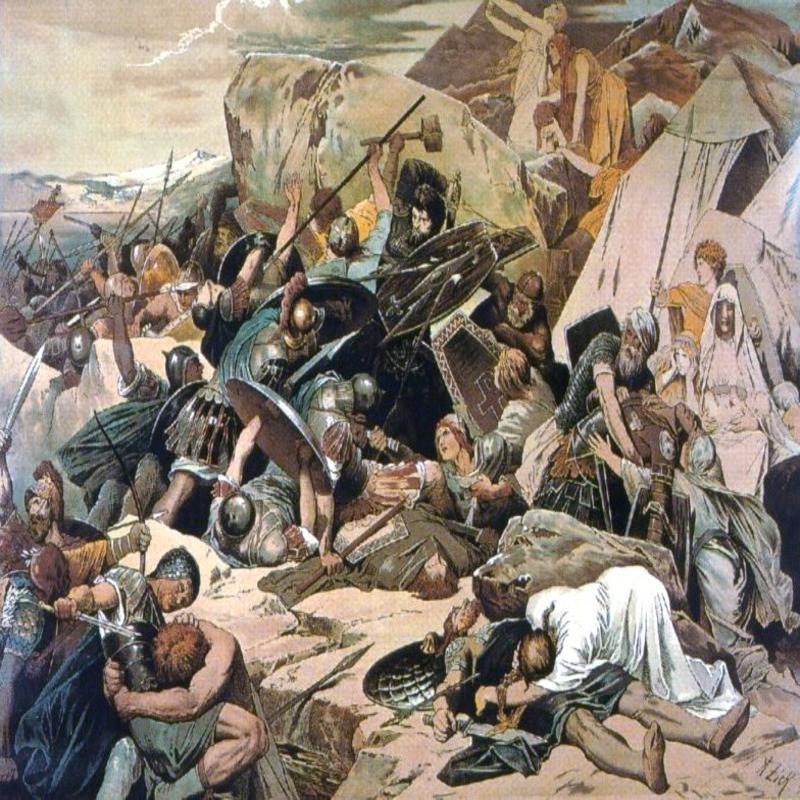

On 10 January AD 532, the City Prefect Eudaemon arrested a number of hooligans following a riot at the chariot races that had resulted in the murder of a man. Most of the culprits were executed in short order but two escaped when the gallows they were standing upon waiting to be hanged collapsed.

The two men, one from the Blue Faction and the other from the Green were soon recaptured but escaped once more this time fleeing to a nearby Church where they sought sanctuary. The Church was soon surrounded by supporters of both the Factions demanding that the men be permitted to go free.

A nervous Justinian, aware that he had already stretched the patience of the Factions to breaking point and not wanting to inflame the situation further announced that the men’s sentence had been commuted from death to life imprisonment and to try and placate them further announced that there would be chariot races held the following day. Both the Blue and the Green Faction remained adamant that their men be released without charge.

On 13 January, a large crowd converged on the Hippodrome to watch the chariot races that had been promised and the tension was palpable. As Justinian viewed proceedings from his royal box in the Imperial Palace overlooking the vast arena he could hear the murmurings, the jeers, and the abusive chants being levelled at both him and his wife. As the day began to draw to its close and following Race 22 the crowd many of whom were by this time clearly intoxicated began to chant in unison Nika! Nika! or Victory! Victory! Justinian tried to address the crowd but was shouted down. They then tried to storm the Imperial Palace and the guards were hard-pressed to keep them out, but they did not go away and for the next five days the Emperor was effectively besieged in his own Palace as the mob rampaged through the streets of Constantinople looting shops and setting much of it alight while he was forced to watch in impotent rage as they torched his beloved Church of Hagia Sophia. In a further attempt to placate the mob he fired several unpopular Ministers but rather than calm the situation this just seemed to embolden them even further.

It seems unlikely that the Nika Riots as they became known were entirely spontaneous. Many leading members of the aristocracy, most of whom had connections to the Factions had long been offended by Justinian’s humble origins, his arrogant manner and his overbearing whore of a wife. That the mob was being manipulated by leading politicians and opponents of Justinian’s reign is borne out by the specific political demands they now began to make. They demanded that the Chief Tax Collector John of Cappadoaccia be removed along with the Magistrate Tribonian who had been pivotal in helping Justinian rewrite the legal code. Justinian indicated that he might be willing to do so but a furious Theodora refused to contemplate any such thing and demanded that not only should they remain but he should stand firm. As a result, the Factions now declared for Hypatius the nephew of a former Emperor Anastasius.

Justinian was at a loss what to do and was all for fleeing the city. He still had access to the sea and boats had been prepared for a swift evacuation, but Theodora was not going anywhere. She may have been born in obscurity, but she would die an Empress. She told her husband in no uncertain terms: “May I never be separated from the purple. If now it is your wish to save yourself Emperor, then it is no problem, for we have much money and here is the sea, the boats. However, having saved yourself consider the day when you would not have exchanged your security for death. Those who have worn the crown should never survive its loss. Never will I see the day when I am not saluted as Empress. Purple makes a fine funeral shroud.”

Justinian was both shamed and emboldened by his wife’s steadfastness and courage. Having regained his composure, he would after all fight for his crown.

A plan was devised for the recapture of the city, and it was a cunning and audacious plan that carried the stamp of Theodora upon it. A popular eunuch by the name of Narses would approach the Factions still populating the Hippodrome to address them on behalf of the Emperor. In the meantime, the General’s Bellisarius and Mundus would ready the Imperial Army to retake the streets.

Narses entered the Hippodrome alone. It was a brave thing to do, hundreds had already been killed and anyone associated with the Emperor was liable to be swiftly dispatched. Carrying a bag of gold, he walked directly over to where the Blue Faction were gathered and reminded them that both the Emperor and the Empress were Blues and that their intended replacement Hypatius was a supporter of their deadly rivals the Green Faction. He then began to distribute the gold among the leading members of the Blue Faction telling them that the friends of the Emperor would always be well rewarded. Following a brief discussion, the members of the Blue Faction began to leave the Hippodrome en masse. It left those remaining stunned, but they had little time to vent their anger for as the Blue Faction left the Imperial troops moved in. A bloody massacre ensued as the much diminished and lightly armed demonstrators were brutally cut down. The troops then stormed onto the streets and over the next three days as many as 30,000 people were killed as the Nika Riots reached their bloody denouement. Order had been restored and Hypatius and many of those who had supported him were rounded up and executed.

In the wake of the Nika Riots Justinian and Theodora rebuilt Constantinople, grand bridges and acqueducts soon adorned the city, spectacular Churches were constructed and Hagia Sophia was restored to its former glory. Together they were to transform it into the most splendid city in the world but in truth it was just papering over the cracks. Justinian had barely survived the greatest crisis of his reign. He was living on borrowed time and like many bankrupt regimes before and since he looked to war abroad to restore his authority at home.

In AD 534 his great General Bellisarius brought to heel the Vandals in North Africa returning to parade their leader Gelimer and vast amounts of plunder around the Hippodrome to cheering crowds. Five years later in AD 539 he invaded and recaptured much of Italy. These were the golden years of his reign, but he knew more than anyone just how overstretched the Empire was and how close it was to economic collapse.

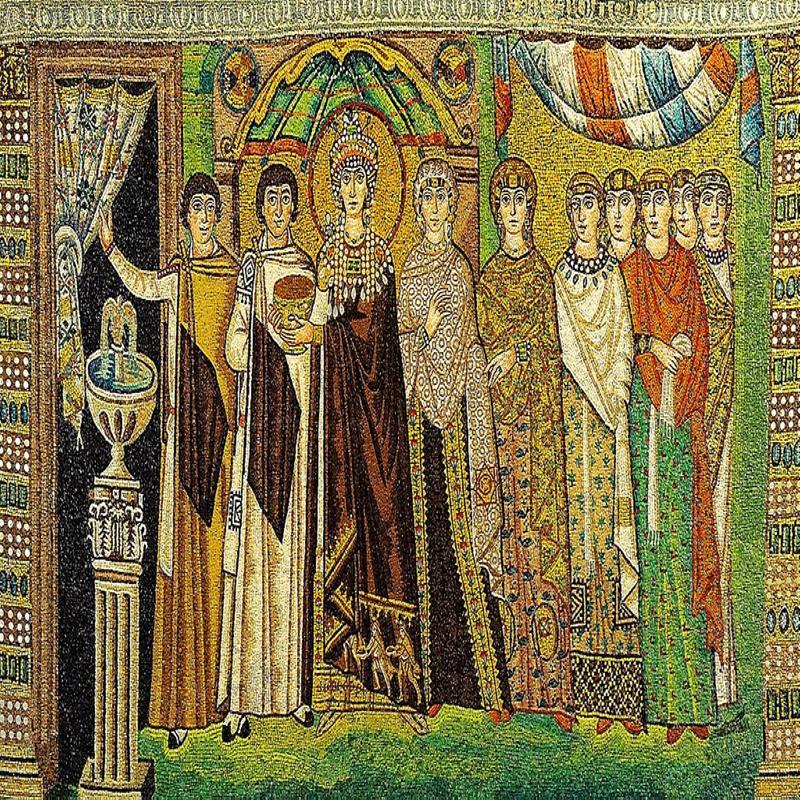

Whilst Justinian gloried in the success of his Generals and fretted over the paucity of his treasury, Theodora dictated domestic policy becoming the great social reformer and her overriding concern was always the position of women. She passed laws that permitted women to divorce and retain control over their own property, she provided mothers with guardianship rights over their children and banned the exposure of unwanted infants. She also abolished the death penalty for women convicted of adultery and instigated it for men convicted of rape.

Theodora also banned forced prostitution and closed the brothels which caused a great deal of antipathy towards her not only from those who made their fortunes from it but also the many rich and powerful men who were their regular customers. She was accused of hypocrisy not only because of her own rumoured behaviour but because she had made her own name performing sexually explicit shows in the very places she was now closing.

Women could still prostitute themselves voluntarily if they chose but she did not expect them to, and her punishments could be harsh for those who did not comply with her wishes. She had a convent built supposedly for women who wanted to escape the brothels which was in reality a prison for those who refused to mend their ways. Here they were kept under lock and key, made to do hard labour and were neglected and half-starved. Indeed, such was the stigma attached to prostitution that many women who became the subject of abuse were afraid to report it to the Authorities in case in they fell into Theodora’s net.

Theodora could be harsh and unforgiving and was utterly ruthless but the reforms she instigated were to prove significant and lasting. She took the rights of women seriously and was to raise their status in Byzantine society to unprecedented levels. Indeed, to the point where they were almost the equal of men making her one of the earliest feminist icons. Even Procopius felt compelled to write “She was inclined to help women in hardship,” though it remains doubtful if this was intended as a compliment.

On 28 June AD 548, Theodora who had been ill for some time, died, aged 48. The likely cause was breast cancer. Justinian was utterly distraught. At her funeral he wept uncontrollably and had to be steadied and led away. It was perceived as unseemly for an Emperor to display such raw emotion in public.

Without Theodora things were never the same. In AD 550 Rome was recaptured briefly uniting the Western and Eastern Empires for the last time earning Justinian the title of the Last Great Roman. But it was also to be a last hurrah.

The latter years of his reign saw the Empire in the grip of plague. A devastating famine had seen taxation rise to punitive levels and following the death of Bellisarius, Justinian had been reduced to buying off the Empire’s enemies. It seemed too many that the Empire was teetering on the brink of collapse.

In his final few years Justinian who had always been renowned as a bundle of energy and was said to be the Emperor Who Never Sleeps could often be found in the early hours wandering the vast corridors of the Imperial Palace alone muttering to himself. Now he could no longer sleep tormented by his loss. His distress gained him little sympathy, many still sought to vent their anger on the peasant Emperor who had married a whore whereas others just thought him senile.

Justinian, the last great Emperor of Rome died neglected and alone on 14 November AD 565, aged 83. He was little mourned.

Tagged as: Ancient & Medieval, Women

Share this post: