Francisco Pizarro and the Conquest of the Incas

Posted on 3rd March 2021

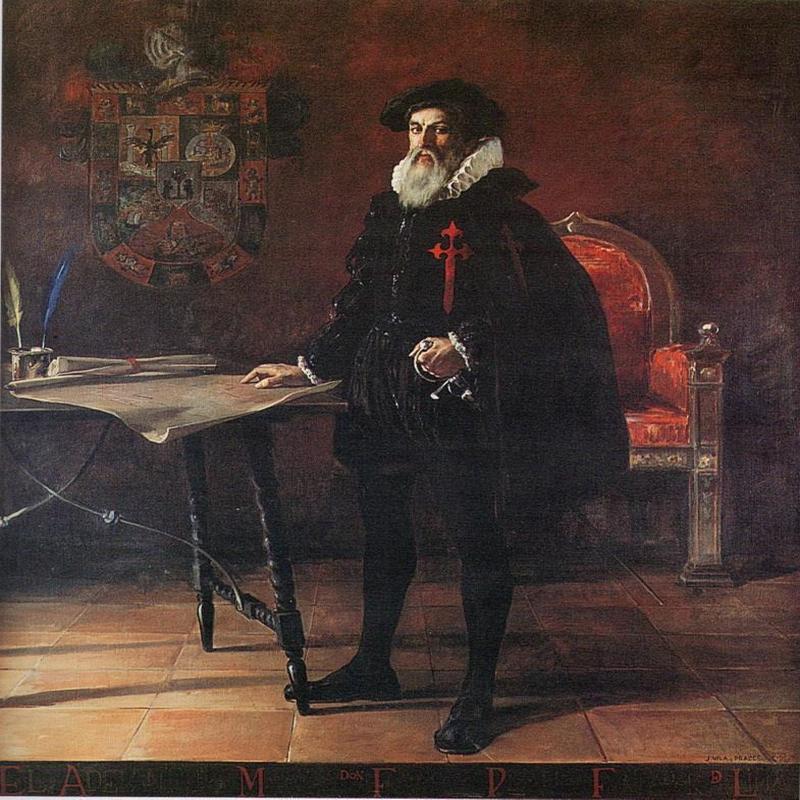

Francisco Pizarro was born in 1474, in the town of Trujillo Caceres in Spain the illegitimate son of an Army Officer and a woman of no background. The product no doubt of an unwanted pregnancy scant attention was paid to him and he had no formal education to speak of remaining barely literate for the rest of his life.

As a boy he worked tending to the swineherd and was later taken to the Italian wars by his father who though a Colonel did nothing to promote his son’s interests. He returned home no doubt better for the experience but with nothing else to show for it other than the reputation as a good soldier.

Uneducated, landless, and always short of money his prospects in the inhospitable and barren wastes of Extremadura were bleak indeed yet despite the lack of opportunity and the hard scrabble just to get by it wasn’t until November 1509 that he volunteered for an expedition to the New World by which time he was already in his mid-thirties - he had decided late in life to make his fortune. It wouldn’t come easy but loyal, capable, and diligent he laboured day and night to succeed and by 1519 was both Mayor and Chief Magistrate of Panama City.

He had also worked hard to amass a small fortune in partnership with long-time associate Diego de Almagro who did not share his thrift but first and foremost a soldier Francisco needed his business partner.

Like many others Pizarro had been excited by the exploits of his cousin Hernan Cortes who in 1521 had overcome the Aztec Empire. He believed he could emulate him at the very least, and he knew where to do so. The fabulous riches of the Incas had long been rumoured, but it was a remote place, the terrain difficult, and its people many and warlike. Even so, Pizarro would do as his cousin had done and conquer these Incas and their fabled land of gold and treasure. But such things are always easier said than done, first he required permission to do so and then he had to raise an army and provide for that army.

His partner Diego de Almagro would be responsible for recruitment while the priest Hernando de Luque would raise funds and purchase provisions. Pizarro would lead the expedition once he had received approval from the Governor of Panama, Pedro Arias Davila.

In November 1524, with 80 men and 40 horses he set off to conquer the Inca Empire. It was not a success, and they did not get far. Battered by storms, harassed by the natives, and close to starvation they never even reached Peru before he returned to Panama somewhat shamefaced but nonetheless undaunted.

On 10 March 1526, he set sail from Panama once more this time with fewer horses but twice the number of men but though this Second Expedition would range far and wide and lay much of the groundwork for what was to come as far as conquest and plunder were concerned it was barely more successful than before except for the seizure of a small craft carrying a little gold and some jewels.

The new Governor of Panama Pedro de los Rios was unimpressed and refused to re-supply the expedition as promised and despairing of Pizarro instead sent ships under the command of Juan Tafur to bring them back.

With Pizarro no nearer reaching his objective and frightened by lurid stories of the vast and savage Inca Army that awaited them, most of his soldiers many of whom were little better than vagabonds and thieves wanted nothing to do with it. When Tafur arrived declaring his intention to return them to Panama, they gathered on the beach in anticipation of doing so but Pizarro stood aside from them and drawing a line in the sand pointed at it with his sword telling them: “On this side lies Peru with its riches. Here Panama with its poverty. Choose each man what becomes a brave Castilian, choose whether to return to Tafur or remain with me, for I go south”.

Pizarro’s words failed to inspire for only thirteen of his men chose to remain but they would soon become known as the ‘Famous Thirteen’ for each one of them would be with him on the day he conquered the Inca Empire.

In the meantime, Pizarro continued his way reaching Peru for the first time in April 1528 and though he didn’t penetrate far he was surprised by the welcome he received. The people were friendly, they presented him with gifts, they afforded the strangers hospitality, and they regaled them with tales of the rich land that lay beyond and the great city of Cuzco ruled by its mighty Emperor. He learned a great deal and did not see in these people the fierce warriors he had been told about, they were soft and easily bullied and intimidated. He returned to Panama enthused and determined to try again convinced that he would succeed a third time. It was not a view widely shared.

Pizarro’s aspirations suffered a setback when Pedro de los Rios refused to sanction a Third Expedition - his plans to conquer Peru were a private business venture and not one he was undertaking either for the Greater Glory of God or in the name of the King. But Pizarro was a grizzled old campaigner as tough as old boots and wasn’t about to give up now - his time might not come again. It was agreed with his business partners that he should return to Spain and approach the King directly.

His ship docked in Seville in the early summer and arrangements were made for a meeting with King Charles V at the Royal Court in Toledo. He arrived prepared with gifts of the fine cloth and gold that had been seized earlier from the Inca craft and a Llama for its novelty value. Cortes was also present to put in a good word for his cousin and remind all concerned of what was possible.

Little of the above was required for Charles could not have been more excited at the prospect of ever more gold and ever more land and so on 6 July 1529 the Capitulation of Toledo granting Pizarro the rights to conquer Peru was signed by Queen Isabella in the King’s absence.

Pizarro had been appointed Governor of any territory he might conquer with full authority to act as he thought proper which displeased his business partner Almagro, as also did his recruitment of his brothers and other assorted relatives to positions of command creating a close-knit family unit to the exclusion of others.

Despite Royal endorsement the money did not exactly flood in and when the expedition sailed from Spain for the New World it consisted of just three small ships, 180 men, and 27 horses. He had however, been provided with the funds to recruit a further 100 men along with arms and provisions upon arrival.

On 27 December 1530, Francisco Pizarro set sail from Panama bound for Peru but as the Conquistadores dreamed their dreams and made slow progress the Incas were engaged in a vicious civil war between the Emperor Huascar and his younger brother Atahualpa. By the summer of 1532 Atahualpa had emerged victorious and with Huascar dead and most of his army advancing on Cuzco, Atahualpa along with 6,000 men celebrated his triumph by taking the waters at the spring town of Cajamarca. In September 1532, Pizarro, who had established the first Spanish settlement in Peru just a few months earlier, set out with 168 men and 62 horses to find him.

Atahualpa was aware of the Spanish presence and appeared little bothered by it sending couriers to Pizarro inviting him to visit his camp. Fearing a trap, on 15 November he sent his brother Hernando and 35 horsemen with greetings for the Inca Emperor. When Hernando met with Atahualpa he was sat upon a litter fanned by servants and surrounded by a great many warriors, nervous and on edge he refused to dismount and instead addressed the Inca Emperor from the saddle: “We have come O Mighty Prince in the name of a still Mightier Monarch across the great waters who having heard of you and your magnificent country has been moved to send this embassy in order to cultivate your friendship and to impart too you the doctrines of the only true faith which we profess and without which you and your subjects will be condemned to flames everlasting. We also come with an invitation from our Commander who would be pleased to have you visit him. We await your orders.”

Atahualpa declined to catch the Spaniards eye and a long silence followed before Hernando added – we await your reply. Eventually Atahualpa did reply: “This is a fast day, and I must keep it but tomorrow I will visit your Commander and let him know of my pleasure, meanwhile let him occupy the buildings on the plaza until I come.”

No doubt having been told by his cousin Cortes of the Aztec fear of horses the finest horseman among them rode at pace towards the Incas making his horse rear and snort in a deliberate act of intimidation, but Atahualpa did not flinch and in an act no less intended to intimidate he ordered that a number of those from his entourage who had displayed fear to be executed the Spaniards eyes.

Atahualpa was not afraid of the strangers and unlike the Aztecs he did not believe them to be Gods. His ambassador who had spent two days in the Spanish camp had witnessed both them and their animals sicken and die - and they were so few. He had a vast and victorious army that would crush, kill and enslave them all except for the three who would be singled out for castration first because they were possessed by evil spirits that had to be freed. They were the man who made their weapons, the man who cared for their horses and the barber for he made their faces shine and revived them.

But that night Pizarro was also making plans of his own; the few small cannon he had, and his musketeers would be concealed in the buildings and aimed at the Inca army. His cavalry, the horse’s necks draped with bells to increase their terrible aspect would charge from the front, the infantry from both flanks, and they would attack with fury, no lives would be spared and Pizarro would make straight for Atahualpa.

But the atmosphere that night was tense and as darkness fell, they prayed together, many thought for the last time: “Fear lies on the men like a black blanket, everyone can now see the madness of this enterprise, all know only a miracle can save us, and we doubted Heaven thought us worthy of a miracle.”

Atahualpa arrived at the Spanish encampment shortly before dusk carried on a litter with four other Lords also carried on litters accompanying him. They were all dressed in ceremonial robes adorned with gold and jewels. The Inca army vastly outnumbered the Spaniards, but they were poorly armed with wooden clubs, stone hatchets, slings, and bows the arrows of which though often tipped with poison were made of flint or even fish scales that could not penetrate Spanish armour.

As Atahualpa entered the plaza of Cajamarca there was no one present to greet him, and it seemed for a moment that the strangers had fled but soon a lone man advanced towards them accompanied by an interpreter. It was the Dominican Friar Vicente de Valverde carrying his Bible. In plain robes he made a poor impression as he invited Atahualpa to enter one of the houses to meet with Pizarro. This was not how you greet an Emperor and so Atahualpa declined demanding instead that the strangers must present themselves before him. Moreover, he had received reports they had taken things that did not belong to them, they must return these things.

Ignoring Atahualpa’s request Valverde now began to lecture him on the One True God. It was long-winded and tiresome and of no interest to the Inca Emperor who interrupted him declaring that no one cared for this mysterious truth when the Sun God was present for all to see. He asked to know the authority for what he said. When Valverde replied that it was the Bible, he held in his hand Atahualpa asked to see it.

Valverde passed it to one his servants who presented it to the emperor. Atahualpa studied it for a moment before declaring “There is no magic in this, it does not speak to me,” and threw it upon the ground.

This was the moment Pizarro had been waiting for, he ordered his gunmen to open fire and his cavalry and foot soldiers to emerge from their concealment and charge: “Now our troops burst out from all the gates and fell upon the defenceless Indians yelling, they cut the unarmed Indians with their swords as if they were carving loaves of bread. It was an atrocious slaughter.”

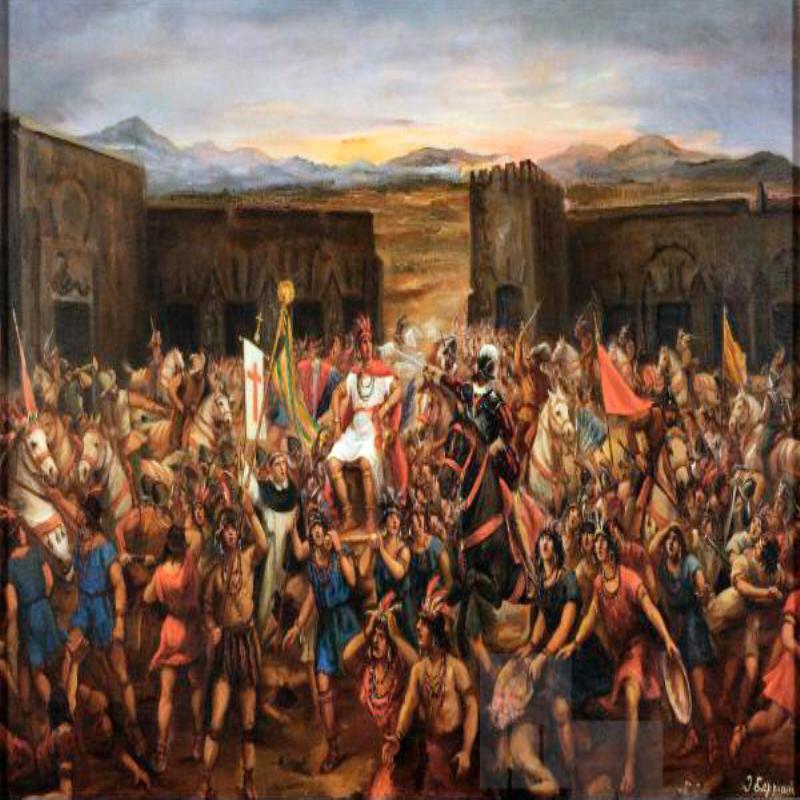

The noise and the smoke and the dust kicked up by the horses terrified the Incas who began to flee in panic as the Spanish cut and sliced their way through them. Pizarro attacked Atahualpa directly killing his entourage and overturning his litter before roughly dragging him into one of the houses where he was stripped of his jewels and fine robes.

The large Inca army had fled without putting up any resistance and no Spaniard had been injured despite killing many hundreds of their enemy. Even so, Pizarro established a defensive perimeter and posted guards should they return. In the meantime, the naked Atahualpa was provided with some coarse cloth and forced to dine with Pizarro who told him that he not only owed him his life but was now his prisoner. The following day the Spaniards looted the Inca camp returning laden with precious booty.

Noticing the fever of excitement that gripped the Spaniards at the sight of gold Atahualpa now made a remarkable proposal. In return for his freedom, he would fill the room they were in with gold and silver as high as he stood, and not only that he would do so within two months. Pizarro was sceptical but if that’s what he said then so be it – he agreed.

Atahualpa would prove as good as his word, Pizarro would not.

Orders were given for Inca officials to gather all the gold and silver they could find in whatever form, goblets, plates, ornaments, jewellery, trinkets, and bring it to Cajamarca. Spaniards who were despatched to supervise the shipments often stole what they had been sent to protect and both robbery and murder became commonplace.

The conquest of an Empire would be put on hold while the Conquistadores enriched themselves which despite their repeated and pious declarations to the contrary was why they were there.

Indeed, the more gold they found the greedier they became, and Pizarro was aware of the rumour circulating among his men that he had struck a deal with Atahualpa to keep secret the locations of where more could be found and so deprive them of their share. Atahualpa then had become a liability in more ways than one and if he believed that delivering upon his side of the bargain would secure his freedom then he was sadly mistaken, it would not even save his life.

The vast Inca Army estimated at more than 50,000 had not been defeated in battle and it was assumed at some point it would seek to free its Emperor. Despite the arrival of Diego Almagro in February 1533 with a further 150 men and 60 horses the Spaniards still felt vulnerable and lived in constant fear of ambush.

It was Almagro who insisted that as long as he lived, he would be the focus of resistance and that as such Atahualpa must die. Pizarro was yet to be convinced while many of the leading Captains believed it dishonourable to renege upon a bargain agreed in good faith.

Pizarro also knew that it was not for a man of his lowly status to pass judgement upon Kings even heathen ones, only a King can kill a King; but Almagro had spread his poison unnerved his men and spread division so on 26 July 1533, Pizarro had Atahualpa tried before a hastily convened Court on charges of idolatry, murder, and treason. The verdict was never in doubt and found guilty he was sentenced to be burned at the stake.

The prospect of being burned alive, horrified Atahualpa and it was agreed with the priest Valverde that should he convert to Catholicism an alternative means of execution might be found. Atahualpa agreed to do so and following his baptism and a perhaps an ill-chosen change of name to Francisco he was garrotted to death in the main plaza of Cajamarca later that same day.

The Inca Emperor’s execution on what were clearly trumped up charges upset some of the Captains who wrote to Charles V in Madrid expressing their dismay prompting the King to reproach Pizarro: “We have been displeased by the death of Atahualpa, since he was a Monarch, and particularly since it was done in the name of my justice” For a time at least Pizarro feared being recalled to Spain to account for his actions.

Following his execution Atahualpa’s younger brother Tupac Hualpa was chosen to replace him, but he died soon after in October 1533. The Spaniards who had not even yet begun to advance upon Cuzco required a compliant Vassal who would nonetheless command the respect of the Inca people. They alighted upon yet another brother, Manco, who they believed had opposed Atahualpa during the civil war.

Francisco Pizarro entered Cuzco on 15 November 1533, there was no resistance. In a little over a year, he had deposed a mighty Emperor with fewer than 200 men and conquered an entire Empire with a mere 500. He dictated a letter for the King in Spain:

“This city is the greatest anywhere in the Indies. I can assure Your Majesty that it is so beautiful and has such fine buildings that it would be unparalleled even in Spain.”

It was a remarkable triumph and greater even perhaps than that achieved by his cousin Cortes but his admiration for the aesthetic qualities and fine architecture of his conquest did not prevent the Spanish from setting about with relish what they seemingly did best – pillage. The palaces and temples of Cuzco were ransacked, it was said that even the graves were dug up so their occupants could be stripped of valuables. Pizarro had ordered that private dwellings be left unmolested so as to not unnecessarily rile the people and that all the treasure seized be handed into appointed officials. Both orders were largely ignored.

Not long after his triumphal entry into Cuzco, Pizarro set off in pursuit of Quizquiz whose large army had remained loyal to Atahualpa. Manco was forced to accompany him and his close-knit cabal of family members.

Manco would prove to be of great assistance in tracking down and defeating Quizquiz but he received little thanks. In fact, the Pizarro brothers treated him appallingly humiliating him at every opportunity. Gonzalo Pizarro even raped his wife.

The ill-treatment he received at the hands of his Spanish captors was so severe that in November 1535, he tried to escape but recaptured was briefly imprisoned until released on the promise that he would retrieve for them a solid gold statue that had belonged to his father. Escorted by just two Spanish guards this time he did escape.

At liberty once more Manco returned to Cuzco where he summoned the Inca leaders to a secret meeting in the Temple of the Sun God:

“I have summoned you all here because we all now clearly know who these strangers really are. They are not worthy people sent by the Gods but children of the devil. We have endured a thousand insults and they have treated us like dogs while swearing to be our friends. Now I want you to send your messengers throughout the land and summon all your forces to gather here in Cuzco in twenty days’ time to attack them. Make sure the bearded ones hear nothing of this and we will kill every last one of them, and then perhaps we will wake from this nightmare.”

The Inca people rallied to Manco and by May 1536, Cuzco was besieged while at the same time Francisco Pizarro was hemmed in at Lima where he was building a new city. In desperation he pleaded with Mexico for reinforcements and three different Relief Columns were sent none of which got through. But the Incas did not have the armaments with which to storm a city and despite their vast superiority in manpower they could not overwhelm a relatively small number of Spaniards and their native allies armed with cannon, muskets and cold steel ensconced behind stone walls. Even so, the Siege of Cuzco would not be broken until March 1537 after ten months of intermittent but often savage fighting during which Juan Pizarro was killed.

As Spanish reinforcements closed in Manco and his supporters fled into the mountains where they fought a successful seven-year guerrilla campaign effectively establishing an independent Inca State. In January 1537, he defeated an army led by his old nemesis Hernando Pizarro at the Battle of Ollantaytambo in which as many as 300 Spaniards may have lost their lives many executed after capture.

Manco’s continued resistance so infuriated Gonzalo Pizarro that upon capturing his half-sister and favourite wife Cura Ocllo in late 1539, he had her stripped naked, tied to a tree, and scourged to death before ordering her body shot through with arrows, placed in a basket and floated downstream for her husband to see.

For a time, Francisco Pizarro had feared he might lose everything but Manco’s revolt was occurring far away and no longer posed any immediate threat and so he could focus upon the endeavour on which he had invested so much time and energy, the building of Lima which he called the greatest thing he had ever done for like many illiterates deprived the majesty of words he possessed a heightened appreciation of the beauty of things.

But he had not been left entirely at peace as he now vied for power and influence with his old business partner Diego Almagro. Charles V had helped fuel the rivalry by appointing Pizarro Governor of New Castile, or northern Peru, and Almagro Governor of New Toledo, or southern Peru.

If the division of responsibility was intended to divide and rule then it worked a treat for the two men were constantly at loggerheads, particularly over who should rule in Cuzco. Almagro also accused the Pizarro’s of plundering Peru for their benefit alone.

The antipathy which was deep and could not be reconciled came to a head when on 26 April 1538 their forces clashed at the Battle of Salinas. Although too ill to participate in the actual fighting Almagro was forced, tied to a donkey and barely conscious, to flee back to Cuzco with the rest of his defeated army but Cuzco provided only temporary refuge and following the arrival of the Pizarro he was tried and found guilty of treason. Upon the sentence of death being passed the grizzled old veteran of so many campaigns fell to his knees and begged for his life. Hernando Pizarro for one was not impressed:

“I am surprised to see you so demean yourself and, in a manner, so unbecoming a brave cavalier. Your fate is no worse than that to have befallen many a soldier before you. Since God has given you the Grace to be a Christian you should perhaps employ your remaining time making up your account with Heaven.”

There would be no mercy.

Diego Almagro was strangled to death in his prison cell before his body was dragged into the main square and publicly decapitated. The Pizarro brothers later attended his funeral.

Francisco Pizarro now had more than he could ever have wished for – titles, honours, wealth, land, power. A man of little background who could barely sign his own name had conquered an entire world but now he got complacent absorbed as he was by his desire to create in New Spain a paradise greater than any to be found in the Old Spain.

He had been warned many times that despite disposing of his greatest rival he still had enemies, none more so than Almagro’s son, also Diego, who remained no less ambitious and now sought vengeance for the execution of his father.

.

On 26 June 1541, Pizarro was dining at his palace in Lima when 25 heavily armed supporters of Almagro stormed in. As his servants tried to keep the door closed the old man rushed for his sword and struggled to put on his breastplate but there was too little time and forced to turn and fight, he struck down two men and was grappling with a third when his throat was slashed. He staggered for a moment before falling to the ground where his enemies were quick to finish him off. As he lay dying, he cried out to Jesus and scrawled the sign of the cross in his own blood.

The veteran Conquistador was dead at the age of 70, his passing more lamented than perhaps history would have us believe.

Three years after the murder of Francisco Pizarro, Manco, the man who had refused to be cowed by him met a similar fate at the hands of the same men. He was playing a game of horseshoes at his mountain hideaway of Vilcabamba when he was stabbed in the back by the assassins of Pizarro to whom he had earlier given sanctuary.

What they hoped to achieve by murdering Manco we shall never know for they were quickly surrounded by his guards and killed to a man.

There is an element of irony, if not exactly poetic justice, that the Conquistador Pizarro’s murder should have been avenged by the Indian warriors of his great Inca rival.

Tagged as: Miscellaneous

Share this post: