Galileo Galilei: An Inquisitive Mind

Posted on 6th March 2021

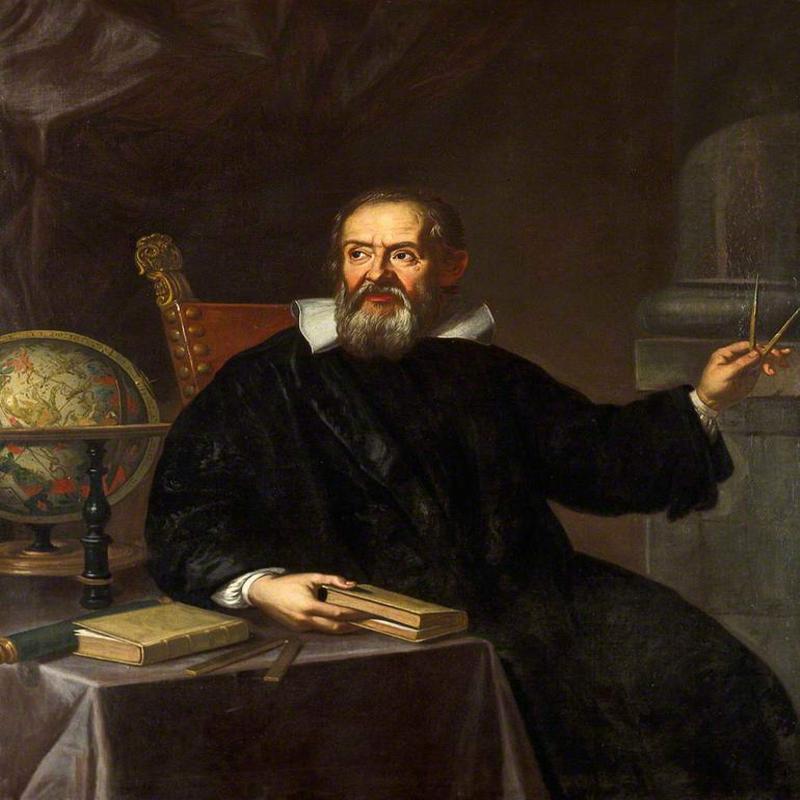

Galileo Galilei was born in Pisa then part of the Florentine Republic, on 15 February 1564, the eldest of six children. Raised a devout Catholic, and he was to remain one for the rest of his life, he briefly considered joining the priesthood but it provided little opportunity for self-expression and even less for the inquiring mind; and so, in part to satisfy his father, he enrolled at the University of Pisa in 1581 to study medicine but this was a profession that had barely advanced since the days of Hippocrates. Its study bored him, and his mind often strayed to other things, things that he saw and wanted to explain. Once, witnessing a chandelier swaying in the breeze he noticed that it took the same time to complete its course regardless of whether it travelled on a wide or narrow arc. It intrigued him and he persuaded his somewhat reluctant father to allow him to study mathematics and natural philosophy instead.

Galileo flourished in academia, despite the curriculum at most Italian Universities being restricted to that considered acceptable by the Jesuits with study contrary to their prohibitions being unwise and ill-considered; nonetheless he didn’t feel over inhibited and while at Pisa invented a forerunner of the thermometer and published a number of scholarly works on the dynamics of motion.

In 1592, he moved to Padua, a place less under the influence of the Jesuits and where appointed chair of mathematics he was able to discourse on a wide range of subjects free of interference.

He soon established himself as a man of letters, but he was no mere theorists or book bound academic, he was a practical man who believed in practical experiment and observable fact. In Galileo’s world something which could be understood should be known about. If the mind was his weapon of choice, then society was his battleground and of uneven temper and lively personality he became animated in the company of others often unbearably so. But it was intelligent conversation and argument that sustained him and with good food and wine a constant companion he sought out both.

In one of his frequent visits to Venice he met a young woman, Marina Gamba with whom he soon formed a relationship that saw her move into his house and bear him three children out of wedlock, two daughters and a son. His name did not appear on their baptismal records, the eldest child, Virginia, being described as “daughter of the fornication of Marina of Venice.”

Following Marina’s death in 1612, Galileo chose not to secure his daughters future himself, but instead committed them both to a convent, their illegitimacy making the dowry he would have to provide upon marriage an expense he wasn’t willing to bear. Whether or not this was an entirely harsh and arbitrary decision it is difficult to ascertain, great honour was attached to those who devoted their lives to God, and he may have been influenced by the young women themselves. If so, they had pledged themselves to a hard life, one of toil and prayer.

Yet, and despite, the isolation of convent life Virginia, now Sister Maria Celeste remained close to her father, and they corresponded regularly. He does not appear to have been so close to his younger daughter Livia, who became Sister Arcangela, as no record of discourse between them exists.

In 1608, the Dutch maker of spectacles Hans Lippershey applied for a patent to secure the protection of his ‘perspective glass’ which had a three-fold magnification. The patent was declined but the details of it soon became public leading to further experimentation in its development. Even so, it remained little more than a novelty item but by the following year it had come to the attention of Galilieo. He would later write: “During reports of a new invention by a lens maker in Holland, I determined to fashion a device for myself, and was to make a considerable improvement.”

And he did increasing its magnification ten-fold causing a sensation and at the same time making his fortune.

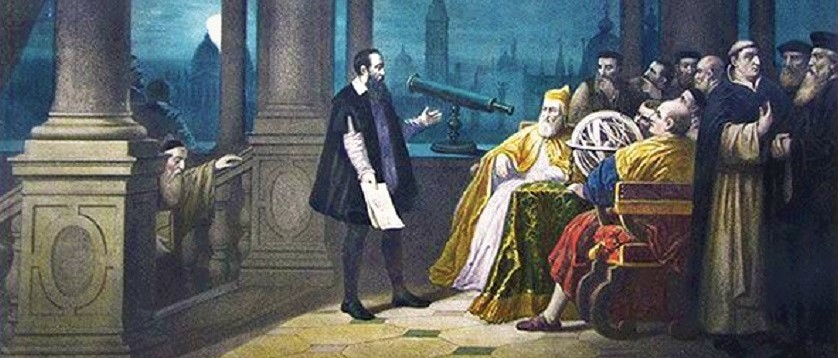

He demonstrated his ‘telescope’ from the top of St Mark’s Tower in Venice and those invited to use it were impressed. It was now possible to see ships on the horizon long before they came within view of the naked eye. For Venice, then one of the leading sea powers in the world and desperate to protect its trade routes, it was a weapon of war, and they not only purchased hundreds of the new eye glass but rewarded its inventor with a life-long pension for his services to the Republic.

It wouldn’t be long before he turned his new telescope to the heavens but first with his financial future secure and his reputation enhanced, he would seek the patronage of a great man and that man was Cosimo de Medici, the ruler of Florence, to whom he wrote repeatedly receiving little in response despite naming the four moons of Jupiter after him and his brothers. He remained undeterred however, and tried once more this time ensuring his letter was delivered with gifts including one of his famed telescopes:

“It is up to our Sovereign whether I spend the rest of my days here in Venice or return to Florence. If I am to return I desire that Your Highness will give me leave and leisure without my being occupied in teaching. Finally, I desire of His Highness that in addition to the Little Mathematician he will annexe the Little Philosopher.”

But it was more his own research and growing reputation as a man of intellect to compare with any found in Protestant Europe that convinced the Medici family, who considered themselves among the avant-garde in all things cultural and scientific to embrace him than any special pleading on his part. Having developed a telescope so powerful that he could study the stars in detail he had made a number of discoveries, not only the four largest moons of Jupiter, but sunspots and the mountains and valleys that dotted the lunar landscape. Indeed, it was his work in astronomy that made him famous or at least notorious, and for which he was well-rewarded being appointed chair of mathematics and natural philosophy at the Court of the Medici in Florence. It would also prompt his fall from grace.

The Catholic Church was at war and had been ever since 31 October 1517, when the German theologian Martin Luther nailed his 95 Theses to the Church door in Wittenberg. The schism within Christianity that ensued as a result would see Catholic and Protestant in conflict for centuries to come, not just on matters of religion but militarily, culturally and in the realm of science and ideas.

Culturally the Catholic Church flourished, its art and architecture, the propaganda of its day, had no parallel anywhere in the civilised world but in matters of scientific endeavour and advancement it was seen as dogmatic and unenlightened. Religious orthodoxy was to be its chosen weapon of choice not intellectual inquiry, and the Inquisition was to be its enforcer.

Rumours of heresy would dog Galileo all his professional life, as it would anyone who expressed an interest in the heavens and drew conclusions counter to those already determined by the Church. The Council of Trent (1545-63) had made clear the Vatican’s position regarding dissent:

“To check unbridled spirits the Holy Council decrees that no one relying on his own judgement shall in matters of faith and morals pertaining to the edification of Christian doctrine, distorting the Scriptures in accordance with his own conceptions , presume to interpret them contrary to that sense which the holy mother church, has held or holds.”

The Catholic Church, along with most educated people held to the Aristotelian geocentric view that the Earth was the centre of the Universe something that was proven daily by the rising and the setting of the Sun. Further proof of this was provided by Scripture:

“The Lord set the earth and its foundations, it cannot be moved.” (Psalm 104)

“And the sun rises and sets and returns to its place.” (Ecclesiastes)

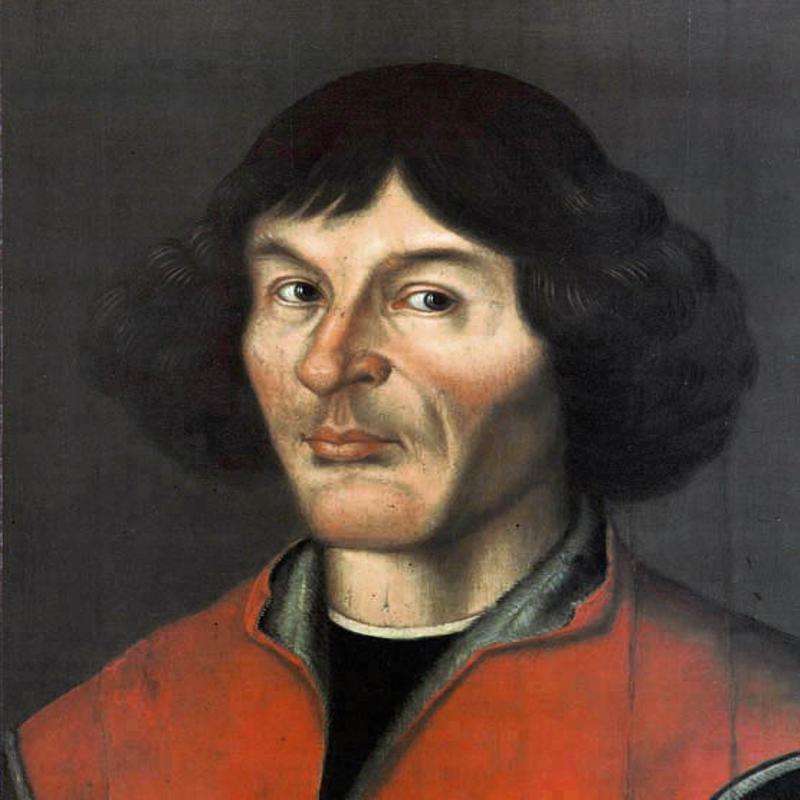

Galileo thought otherwise and shared the opinion of the Polish astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus that the planets, including the Earth, revolved around the Sun which lay at the heart of the universe. To share the heliocentric view was considered at best an eccentricity common to the untamed mind or at worst a great heresy that denied the veracity of the Bible.

In any case the very idea that the Earth moved was absurd, and certainly at the speeds Copernicus suggested. If that was the case people would not be able to stand up, it wouldn’t be possible to breathe, towers would topple over, bridges would fall, the seas would swamp the land and objects would be flying through the air like the rain falls from clouds.

But Galileo knew this wasn’t so and he conducted an experiment to prove it: if one sits upon a horse and drops a ball, it falls straight to the ground but if one rides that horse at a gallop and drops a ball it still falls straight to the ground. It was a ‘thought experiment’ only he did not have to carry it out for he knew it to be true.

In December 1613, in a discussion with Cosimo de Medici’s mother, the Grand Duchess Christina, the philosopher Cosimo Boscaglia suggested that even if Galileo’s theory of the Earth’s motion had some validity in science it was still obviously contrary to Holy Scripture. When Benedetto Castelli, who was also present, rushed to his friend Galileo’s defence the Grand Duchess cast doubt on the authenticity of her Court Philosopher’s views by quoting passages from the Bible, in particular the account of Joshua at the Battle of Gibeon when the Lord commanded the Sun, and not the Earth, to remain still. Surely then, his theory that it was the Earth that moved was contrary to Scriptural teaching not only contradicting the Bible but also by necessity the Word of God.

Although the discussion had been conducted amicably enough and had in no way been accusatory Castelli felt obliged to inform his friend of its content. Galileo incapable of letting sleeping dogs lie in matters of intellectual discourse responded by letter. He agreed that the Scriptures did not err arguing instead that it was they who interpreted them who erred; and that if the science appeared to contradict the Bible then it wasn’t because the science was mistaken but that the Holy Scripture had been wrongly understood, and that all great men of science, their work would not permit them to do otherwise, questioned the literalness of Holy Scripture but this wasn’t to cast doubt upon its validity or dispute as to the existence of God - but to dispute at all with the Church on matters of theology even when it was dressed up as scientific method was a perilous business.

A copy of his letter to Castelli found its way into the hands of the Dominican Friar Niccolo Lorini, a long-time critic of the scientist who now used it to openly attack Galileo finding a willing audience among colleagues who despised his arrogance and the Jesuits who feared his unorthodoxy. Preached against from the pulpit of Churches the length and breadth of Italy the demand in religious circles that he be investigated for heresy could no longer be ignored.

Under the protection of the Medici the disputatious Galileo felt confident that he could convince the doubters in Rome of the veracity of the Copernican theory, and he looked forward to meeting with the Grand Inquisitor Roberto Bellarmine, who sixteen years earlier had presided at the trial of Giordano Bruno.

Despite his reputation as an unworldly man of cloth and cloister Galileo had heard that the Grand Inquisitor was also a man of great intellect with a keen interest in astronomy. He looked forward to a lively discussion that would put to rest once and for all the ridiculous allegations of heresy being made against him and had been encouraged in this view by the many positive meetings he’d had with other Cardinals and leading religious and political figures during his stay in Rome.

Galileo was naive in his assumptions however, for whatever the Cardinal’s personal passions in matters of religion he was orthodoxy itself, and there were others who also doubted Galileo’s own powers of persuasion among them the Tuscan Ambassador who wrote to the Medici in Florence: “Galileo is passionately involved in this fight of his, and he may well get himself into serious trouble along with anyone who shares his views. This business not a joke and the man is staying here under our protection.”

Just three days before he was due to meet with the Cardinal the Holy Office of the Inquisition gathered in the Collegio Romano and voted 11 to 0 to ban the teachings of Copernicus and denounce the theory that the Sun was the centre of the universe as contrary to Biblical teaching and that as a consequence the espousal or repetition of such was an act of heresy. All the Polish astronomer’s works were then placed on the Prohibited Books Index.

There was no longer any discussion to be had and when Cardinal Bellarmine, on Pope Paul V’s instruction met with Galileo it was merely to be told of the Inquisitions earlier decision and that he was not to defend Copernicus’s position but to remain silent on the issue.

He was also ordered “to abandon completely the opinion that the sun stands still at the centre of the world and the earth moves, and henceforth not to hold, teach, or defend it in any way whatever, either orally or in writing.”

In private conversation however, Cardinal Bellarmine had made it clear that the Church was not averse to change but to do so it needed proof, not theory, but physical proof - Galileo was determined to provide that proof.

He believed that he could validate the Copernican view by showing that the tides of the sea were caused by the earth’s rotation, that he failed to do this even to his own satisfaction let alone anyone else’s was not only a personal humiliation for a man who had previously considered himself flawless in such matters but also heaped further suspicion upon his motives for pursuing such research.

Following the failure of his experiments into the mechanics of tidal movements he wisely steered clear of further controversy.

On 8 July 1623, the brief papacy of Gregory XV ended and with it, Galileo hoped, the Vatican’s hostility towards him for the following month the Conclave of Cardinals elected his friend and long-time admirer Maffeo Barberini as Pope Urban VIII.

Galileo’s daughter Maria Celeste, writing from her convent of San Matteo in Arcetri expressed her delight at the elevation of Barberini and that her father and the new Pope remained friends and were still corresponding:

“Father, the happiness I derived from the letter written to you by the Supreme Pontiff was indescribable. His note so clearly expressed the affection this great man has for you.”

Galileo met with his friend the Pope in the Vatican and it was while strolling through its grounds, admiring its garden and pointing to the heavens that he sought his permission to write his great book on cosmology. Urban declared that he would not stand in the way of its publication, nor would he inhibit the debate on its findings, and as an old friend he assured Galileo that he need not fear of persecution as long as he remained Pope. But there were caveats; he must write only hypothetically of Copernicus while making clear that his was a theory and no more. He also demanded that his views as Pope, and therefore those of the Church were given equal weight and consideration in the text.

Galileo’s dialogue ‘Concerning the Two World Systems’ took five years to write and wasn’t completed until Christmas Eve 1629 but even then, he remained wary of making it public despite the Pope’s assurances and it wasn’t made available until 1632.

Galileo’s reluctance to publish became clear when he was found to have hidden his scientific discourse beneath the thin veneer of a social satire in which the views of the Catholic Church were spoken by a character named Simplicio, or the Simpleton.

To place the words of the Pope in the mouth of an idiot was a step too far and Urban, personally affronted, now came under renewed pressure to prosecute the incorrigible old heretic. Already engaged in the Counter-Reformation, threatened by the Turks in the East and embroiled in the Thirty Years War in the West, he now abandoned his old friend.

In September 1632, Galileo was summoned to appear before the Grand Inquisitor Vincenzo Maculani to explain himself. He could either come to Rome of his own volition or be brought to the city in chains. He chose the former but even so delayed his arrival until February of the following year.

Galileo vehemently denied that he had sought to defend Copernicus in his book or had in any way mocked the Church. He was, he said, a faithful and devout Catholic who believed in the literal truth of the Bible. His book was merely a summation of the geocentric and heliocentric view of the heavens as already expressed, and no more. But it was clear to anyone who had read it that he advocated for the latter and mocked the former. Galileo declared that if this was so then it was unintentional and regretted that he had written it in such a way that it could be so misunderstood; but at 70 years old, in poor health and threatened with torture he caved in completely.

On 22 June 1633, Galileo appeared before the Inquisition to learn his fate and he cut a sorry figure, aged and stooped his movements were slow and deliberate, his voice weak and faltering, his eyes moist. He even at times seemed a little confused but if this was exaggerated to elicit sympathy, he received none.

Informed that he was ‘vehemently suspect of heresy’ and guilty of advocating for a theory already found to be contrary to Holy Scripture and in violation of a previous agreement not to do so he was sentenced to indefinite imprisonment in the dungeons of the Inquisition in Rome. Following intensive lobbying on his behalf by the Medici family he was released into house arrest where he was to remain for the rest of his life.

It had not come easy to the Catholic Church to openly condemn their great man of science and it was perhaps for this reason, and this reason alone that he had avoided torture and a sentence of death, but with his works past, present, and future placed on the banned list (where they would remain for the next 250 years) his career was effectively over.

On 2 April 1634, Maria Celeste died aged 33, she had been her father’s rock in hard times and her loss was a heavy blow for the old man to bear. Restricted to the confines of his home and receiving few guests he revisited his early work on the laws of motion writing up his notes that had lain dormant for so many years.

Using his invention of the ‘Inclined Plane’ he judged how fast a ball would roll over varying distances as timed by the swing of a pendulum. He measured how in 1 unit of time it would roll 1 unit of distance but in the next unit of time it would roll 3, and then 5, and then 7, and so on.

At the age of 74, by means of his ‘Odd Number Rule’ and resuming the research he had begun as long ago as 1592 when it was said he dropped objects from the Leaning Tower of Pisa to disprove Aristotle’s theory that objects of the same material fell, or travelled through the air at different speeds according to their weight and mass, he had uncovered the rules of acceleration and established a universal law for accurately predicting the motion of objects in the real world. But proscribed throughout Catholic Europe his book ‘The Two New Sciences’ could only find a printer in the Protestant Netherlands where it was published to very little fanfare and achieved only a meagre distribution.

Galileo, who had always enjoyed being the centre of attention, spent his final years in isolation from the literary salons and intellectual soirees he had so often lit up by his presence instead under house arrest he merely complained to his servants of the cold and the aches and pains of old age.

That was the price he paid for his notoriety, though many had rather he’d paid with his life.

Galileo Galilei died on 8 January 1642, aged 77, repentant only of the fact he may have imperilled his soul.

Tagged as: Ancient & Medieval

Share this post: