Gladiators

Posted on 24th August 2021

According to legend, the first gladiatorial combat took place at the funeral of the distinguished aristocrat Junius Brutus Pena in 246 BC. The spectacle had been arranged by his family in his honour. We don’t know why this was considered a suitable tribute but in a very short time the sight of men fighting in the arena became one of the biggest attractions in Rome, though it was never as popular as horse and chariot racing.

As a result, Gladiatorial Schools were to crop up all over southern Italy but just as sport is now it was less a performance of skill and physical prowess than it was a commercial exercise.

Gladiators were more often than not slaves and the owners of the schools would attend the slave auctions, salt mines, quarries and labour camps to find and bid for the finest physical specimens and as most male slaves had been captured in battle there were usually a high number of warriors among them.

Once purchased the slaves would be chained and taken to their new owners Gladiatorial School where they were housed in communal barracks, placed on a high energy diet, subjected to a rigorous training regime and taught the art of one-on-one combat with the weapons that would commonly be used in the arena.

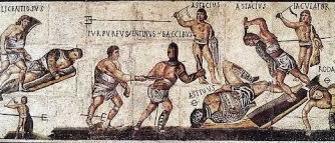

These would be the Gladius, or short sword often used with a small round shield known as the Parma; the Hasta, a javelin used with a large oblong shield; but the most popular with the crowd was the Trident, a 52 inch long three-pronged spear used along with a net called the Iaculum to ensnare their opponent. It was the most difficult form of combat to master those who used the Trident, were both highly skilled and greatly prized.

The training would take place in an area with room set aside for spectators to watch to get the combatants used to the noise of a crowd.

The owner of a Gladiatorial School would be keen to secure his property where he could, and Gladiators were not expected to enter the arena without protection. However, armour itself was expensive and few owners were willing to spend too much money on what was after all an expendable commodity. As a result, they would often wear a tough leather tunic along with the Galea, a visored helmet, though they were provided with an Ocrea, a metal legging to be worn on that part of the that leg that could not be protected by the shield.

Though they were worked hard the Gladiators were always well fed, well rested and received the best medical attention. For many, they also had their first ever bath.

Gladiators were expected to fight, and punishments could be harsh for non-compliance but there was no desire on the part of the owner to physically damage what was valuable property and so those who lacked courage or were simply not up to the job would be sent straight to the arena and used as Noxii, or hurtful ones, easy kills to satisfy a crowd’s bloodlust.

The trade in Gladiators was closely monitored by the Authorities and subject to official supervision for these men were ferocious warriors by profession and were considered dangerous, savage and barbaric by nature. They could not simply be let loose on society – the lesson of Spartacus was not easily or quickly forgotten.

Although, they were bought and sold as slaves to be a man captured rather than killed in battle was to be unworthy of life and so to die in the arena was a redemption of sorts.

Despite being a brutal existence and one of doubtful longevity nearly half of all known gladiators were volunteers because for the poor or non-citizens of Rome the Gladiatorial Schools provided not only accommodation, regular food, and a trade but the opportunity for riches.

A successful gladiator if he won over the crowd could acquire celebrity status and become very rich. Indeed, the Emperor Tiberius paid several of them as much as 100,000 sesterces while Mark Antony is known to have employed gladiators among his personal bodyguard.

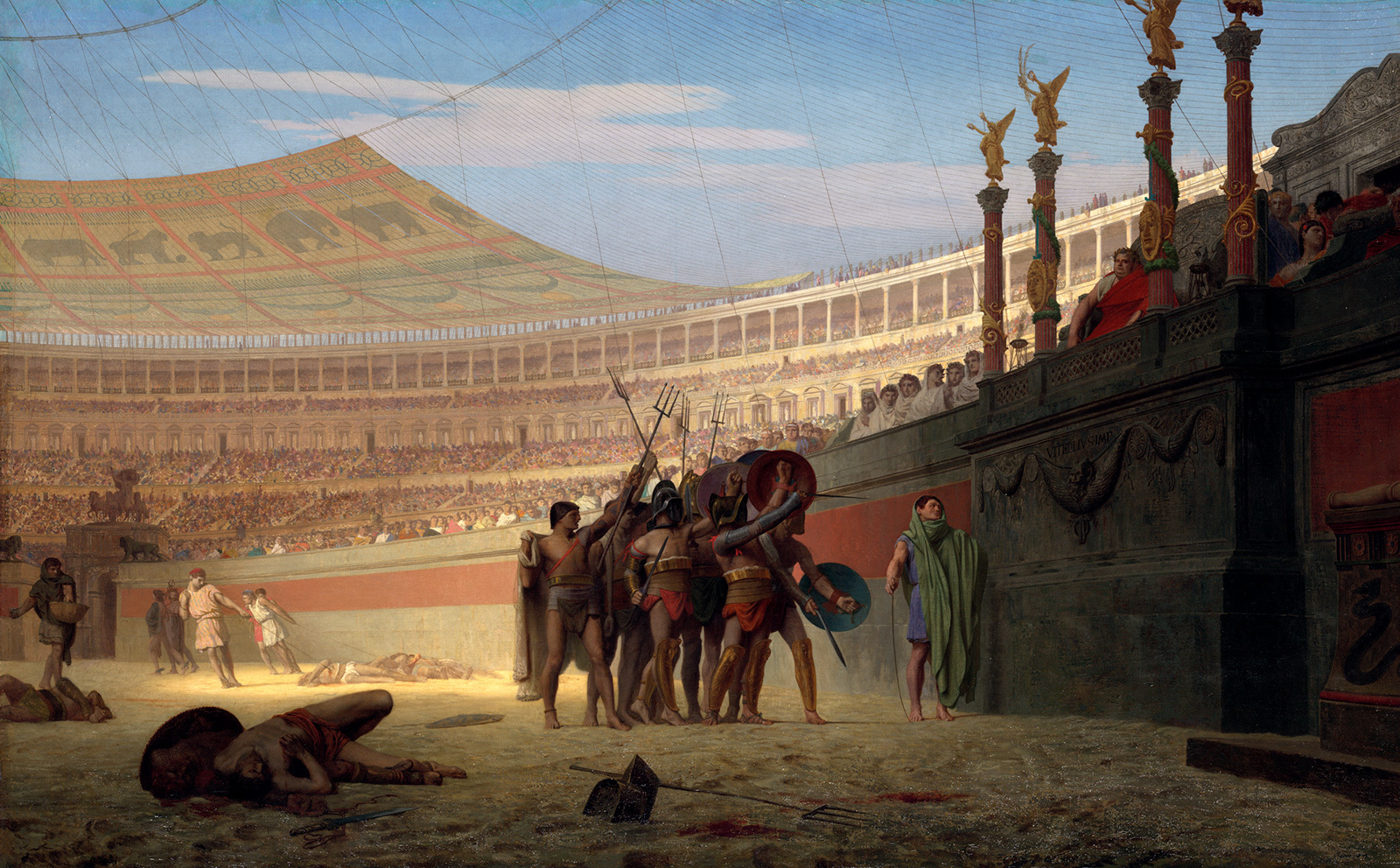

In AD 80, the Colosseum was formally opened by the Emperor Titus. It which had been commissioned by his father and predecessor Vespasian ten years earlier and paid for by the treasures stolen during the destruction of the Jewish Temple in Jerusalem.

Holding more than 50,000 people the Colosseum had been built not only to symbolise the grandeur of Rome and the Flavian Dynasty but provide the bread and circuses that would placate the mob. It would soon become the fulcrum of entertainment in Rome and the arena for gladiatorial combat where the crowd liked to see their favourites fight, and none more so than the female gladiators who they enjoyed for their erotic and they would claim comic value.

The female gladiator Mevia who would hunt boars in the arena with her breasts exposed and armed with a spear was always eagerly anticipated as were naked black women from Ethiopia considered as they were to be wild, exotic and direct descendants of the Amazon.

But there was some critical of gladiatorial combat in Rome and a few prominent Senators and philosophers expressed their opposition not on the grounds of the brutal spectacle itself but rather the loss of control displayed by the crowd.

The Emperor Marcus Aurelius thought it boring but did nothing to curtail it while other Emperors enjoyed performing in the arena. Nero entered the chariot races as a contestant, but it was Commodus who liked to don armour and spill blood. It was said that he once displayed his skills as an archer by killing over a hundred lions in a single day – no doubt from a place of safety.

The political elite of Rome often frowned upon such antics, but the people loved it.

Death for one or other of the contestants was considered the right and proper outcome of any gladiatorial combat but such a result could be ruinously expensive for the loser’s owner and the people were also keen to see their favourites return to fight another day, so death in any fight between gladiators was actually quite rare. What was important was they fight properly and put on a show, rolling on the ground frantically clawing at each other and pulling hair was not acceptable. They were first and foremost entertainers.

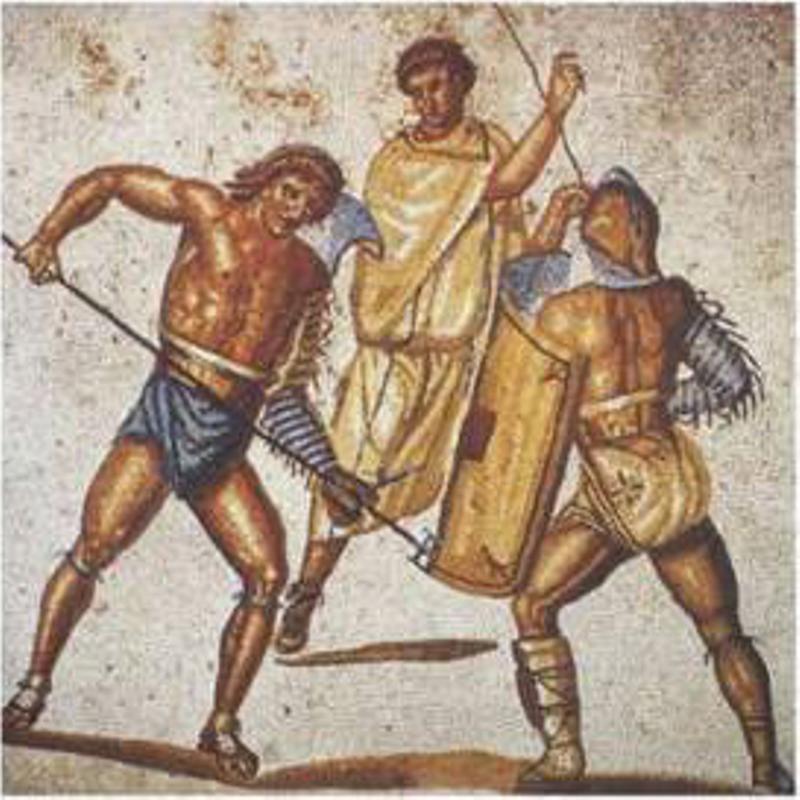

Gladiatorial combats had an arbiter who would guarantee that there was no cheating, that the combat wasn’t feigned and would intervene if the crowd were displeased with what they were seeing.

The fight would come to an end if someone was killed, were too injured to continue or if one the combatants raised his finger to indicate that he was beaten. The arbiter would then refer the outcome of the contest to the Editor who would make his decision based upon the mood of the crowd.

If the losing gladiator had fought well, and the crowd wished to see him fight again then he would live, and it was only if the mood of the crowd was particularly ugly that the decision be made to end his life. He would then be finished off by his opponent or if the gladiator concerned was unwilling to do so, would have his throat cut by one of the soldiers lining the arena.

The Emperor, who would often attend the games did not give the thumbs up for life, or down for death, as is popularly believed though he could intercede in events if he so chose.

Gladiatorial displays were always much anticipated, and posters would appear around the town hosting the event days in advance, the names of the gladiators expected to fight would be publicly announced, graffiti would be scrawled on walls praising some and mocking others and bets would be laid.

The combatants entered the arena in full armour to parade before the crowd and have their names chanted and be cheered or jeered depending on their popularity. They would then leave but return later as the climax to the day’s events.

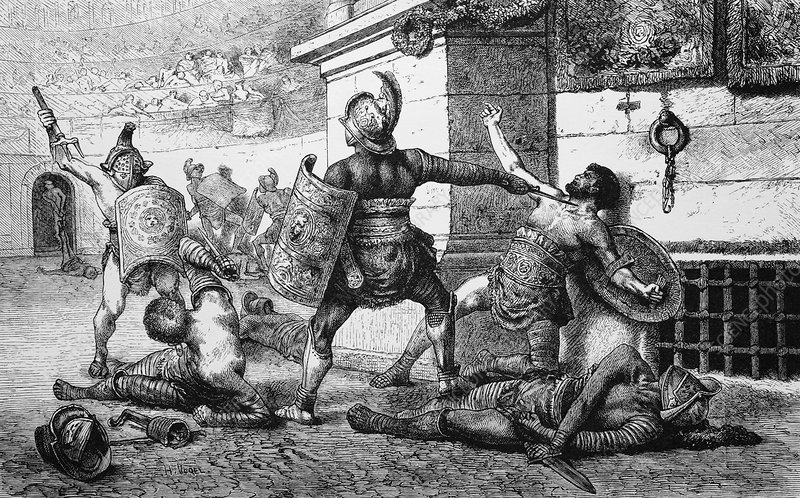

In the meantime, the spectacle would begin with a display of exotic animals that were then hunted down and killed by men and women on horseback before prisoners would then be brought into the arena to be exposed to savage, half-starved beasts such as lions, tigers, or bears. With much of their bloodlust already sated the gladiators would then appear usually in pairs.

Though they had been trained to kill and would aim their blows at the major arteries under the arm, behind the knee or go for a stomach wound that would result in a slow and lingering death it was blood more than a kill that the crowd desired – a good fight was everything, and a particularly outstanding gladiator could earn his freedom in the arena.

It was described how a fight between two well-known and popular gladiators known as Priscus and Venus ended when they both indicated that they were beaten at the same time but so impressive had their combat been that the Emperor Titus declared them both a winner and awarded them with a Rudius, a wooden sword that was a symbol of their freedom.

Living together, training together and socialising together many gladiators shared a comradeship like that of soldiers and when, as on occasions they would, friends might have to meet each other in the arena experienced gladiators could always ensure each other’s survival by guaranteeing a good show regardless of the result.

The aim in the end was to live long enough gain one’s freedom and to make enough money to retire and those who did so were often able to live out the rest of their life in some comfort and with the respect that comes with having hero status.

Yet there always remained the risk of being forced out of retirement and back into the arena at a Senator or the Emperor’s request.

Tagged as: Ancient & Medieval

Share this post: