Gordon of Khartoum

Posted on 17th January 2021

Gordon of Khartoum is one of the great names of British history, an icon of Empire and the hero to a generation perhaps like no other; he epitomised the Victorian ethos of Christianity, Commerce, and Civilisation and the God-given right of every Englishman to bring it to the world at the point of a bayonet if necessary, and to die in the cause if need be.

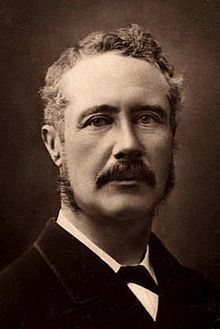

He was born Charles George Gordon in Woolwich south-east London on 28 January 1833, into a military family. His father was a General serving with the British army, so it was perhaps inevitable that the intense and earnest young Charles was going to follow in his father's footsteps.

Even so he did not particularly impress as a cadet and was commissioned as a lowly 2nd Lieutenant in the Royal Engineers serving briefly in the Crimean War but given the somewhat maverick tendencies he had displayed even as a child it is perhaps unsurprising that he never took easily to military discipline, just as he was often driven to distraction by the tedious months of idleness that life in the army often provided.

In 1860 he volunteered to fight in the Second Opium War and following its successful conclusion decided to stay on and serve in the Chinese Emperor's army and it was during the subsequent Taiping Rebellion that he was to make his name.

His time as an Officer in the Chinese Imperial Army was one of unprecedented success and the troops he commanded became the aptly named Ever Victorious Army as they swept all before them, and his image as the man who crushed his enemies armed only with a cane and a Bible became a familiar one in the British newspapers and periodicals of the time as their readers avidly lapped up the stories of his exploits.

A grateful Chinese Emperor showered him with honours and gifts, and he was promoted to Lieutenant-Colonel by the British Army in recognition of his achievements, and over the next few years he was to become effectively a roving ambassador for British Imperial and military might. To the Victorians he was the unflappable and invincible "Chinese Gordon" and was held in high regard by a public that loved its "Boy's Own Heroes."

By 1864 he had returned to Britain where in his role as a trouble-shooter for the British Government he served on International Commissions, repaired fortifications, and maintained British military cemeteries abroad among many other things. Indeed, there seemed little the ubiquitous Gordon couldn’t do.

Building the fortifications that defended the Thames Estuary from the threat of invasion bored him however, and he spent much of his time in Gravesend helping homeless boys to find shelter and young men employment; leading some to question his sexuality but there is no evidence that he ever had a close personal relationship with anyone declaring that God and the Army left him no time for such things. He also donated most of his earnings to local charities.

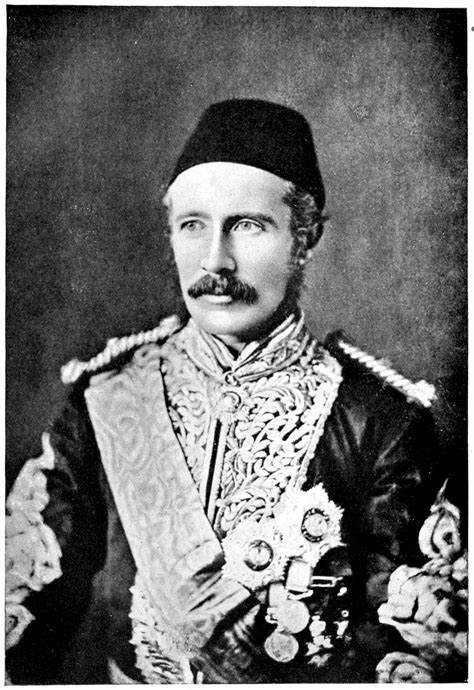

In 1873, he received a request from the Egyptian Khedive to serve in the troubled region of the Sudan and having successfully petitioned the British Government for its approval he accepted the commission. Despite an apparent unwillingness to work with others and his frequent and flagrant disregard for orders he still managed to impress his employers.

Following yet another disagreement with those nominally in charge he threatened to resign but the Egyptians needed Gordon and he knew it. So, it came as no surprise when in 1876 the Khedive offered him the Governorship of the Sudan with absolute control over its affairs. It was the biggest opportunity of his life, and he grasped it with both hands.

The Sudan was a lawless land troubled by warring tribal factions that had become a thriving centre of the slave trade and Egyptian control for what it was worth was restricted to the major town, beyond which there was no effective government to speak of. Gordon certainly had his work cut out but during his years in charge he managed to bring some administrative order to the chaos. He imposed laws where previously there had been none, established trading posts along the banks of the Nile, and suppressed the slave trade but in doing so he adopted brutal methods making liberal use of the gallows and many enemies as a result.

Gordon was not one to tolerate dissent and those who questioned the ferocity of his punishments were either ignored or dismissed from their posts, firm as he was in the conviction that he was doing God's work.

With his work in the Sudan completed in 1880 he returned to Britain for a short period before departing again for China, then travelling on to Mauritius, and later making a pilgrimage to the Holy Land though some of his critics suggested it should have been the other way round and the Holy Land should have made the pilgrimage to him.

The sense that he sat at God's right hand was evident to all who met him and was further endorsed by his declaration that he had discovered from his own research all there was to know about the life of Jesus Christ. Never a social man he believed emotion best filtered through the lens of religious conviction and was most comfortable in the company of other Evangelical Christians where the Bible dominated discussion and God's Good Grace remained paramount.

When he again returned to Britain he was promoted to the rank of Major-General as the requests for his services continued to flood in. Finally, he accepted the offer from King Leopold of Belgium to become Governor of the Congo.

In 1881 a revolt broke out in the Sudan led by Muhammad Ahmed, the son of a boat-builder who refusing to follow his father's profession had instead devoted himself to religious study. He believed in a strict adherence to the Qu'ran and that any deviation from it or devotion to another faith was punishable by death.

He also believed himself to the Mahdi, the Prophet who would emerge to redeem Islam at the End of Times, and he had the gap in his teeth and the mole on his cheek to prove it. He was the Chosen One he said, who had returned to claim Dominion over the entire Islamic World, and he declared Jihad, or Holy War and the people flocked to his cause.

The Egyptian's were totally incapable of quelling the revolt, they had underestimated the influence and popularity of the Mahdi and on the few occasions their forces did confront the rebels they were easily brushed aside. Within a few months they had ceded most of the Sudan and had been forced back behind their fortifications.

The British Government advised the Khedive to withdraw all Egyptians from the Sudan and abandon the territory to the Mahdi but instead he chose to employ a British Officer, General William Hicks, to lead an expedition to put down the revolt. Provided with an army, many of whom had only recently been released from prison for previously deserting their posts, he remained confident that he had the wherewithal to put down a rabble of spear-wielding natives. So, he set off down the Nile with 8,000 men armed with modern weapons and commanded by British Officers convinced that he would return within a few months with the head of the Mahdi.

Reaching his destination in November 1881, Hicks set off inland through the arid and seemingly endless desert of the Sudanese hinterland. The Mahdi, however, refused to give battle, so on and on Hicks and his army marched under a burning sun with glazed eyes and parched throats. The exhausted and demoralised army of Hicks Pasha had been led into a trap by treacherous guides and by the time the Mahdi did attack they were in no fit state to fight, and Hicks and all but 300 of his men were killed.

By 1882, Egypt was effectively a British Protectorate and by taking control of the Suez Canal the vital lifeline to trade with its Eastern Empire any threat to Egypt now endangered the security of the British Empire; and the Mahdi’s stated aim of bringing the whole of the Islamic world under his power and control if successful would almost certainly bring down the British Government.

The public were outraged by the events in the Sudan and demanded that action be taken against this man who had killed a British General and dared to challenge the Empire.

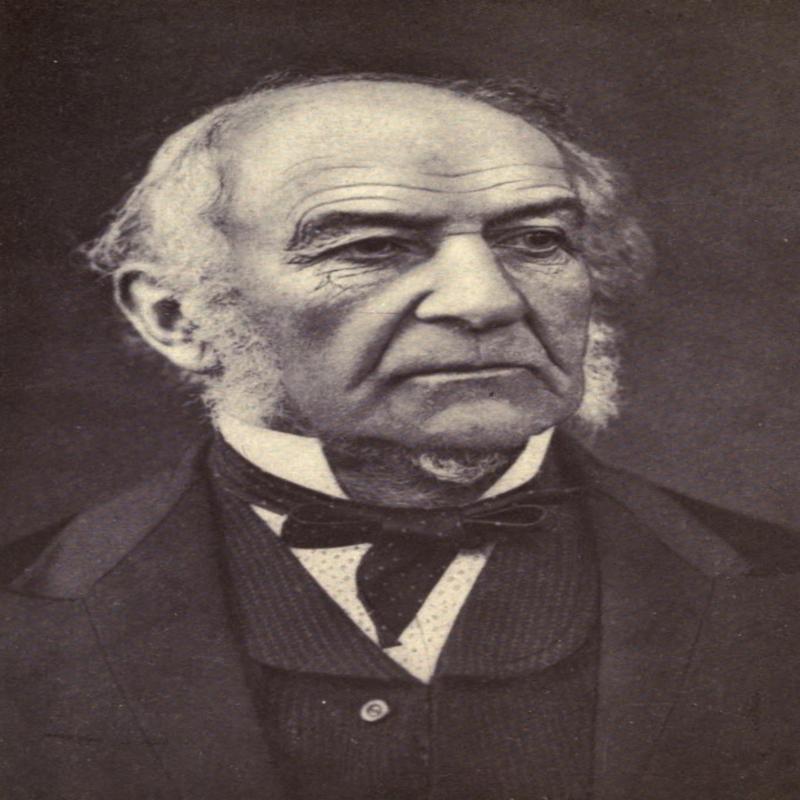

But the Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone was disinclined towards Imperial adventurism for it was not only politically highly charged but ruinously expensive. He was loath then to commit a British army but to avoid a vote of Censure in Parliament he had to be seen to be doing something.

Charles George Gordon was not a physically impressive man short, narrow shouldered and slim hipped but even, so he struck an imposing figure, always ramrod-straight with a deep resonant voice, immaculately turned out and rarely reticent in displaying the adornments of his rank. An Evangelical Christian who always kept a copy of his pocket Bible about his person, he was messianic in appearance, believed in reincarnation, and claimed to have found the true burial place of Christ. He was also a confirmed bachelor frowning upon emotional and overt displays of affection who would do things his way he said, because he was right, and he knew he was right because of his special relationship with God.

An expert on the Sudan and a national hero - what better man could there be to go to the Sudan and deal with this mad mystical prophet who had stirred up the natives than another mystical prophet. The cry soon went up - Send for Gordon!

In December 1883, the British Government ordered the Egyptian's to abandon the Sudan.

They then approached Gordon and requested that he travel to Khartoum with strict instructions to oversee the safe evacuation of all Egyptian and European citizens.

Gordon accepted the role and its strict remit but upon his arrival in Cairo he was again offered the Governorship of the Sudan with executive powers. He would once more be its effective ruler and as such he now had no intention of abandoning it. He would oppose and defeat the Mahdi even if the forces at his disposal to do so, 7,000 demoralised Egyptian troops and some unreliable Sudanese Militia, were insufficient to the task. But he would succeed because it was God’s Will that he should do so, and he also had a plan.

Whilst he was in Cairo he approached a former adversary and slave-trader Rehman Al-Zubayr (Zubair Pasha) who still had considerable influence in the Sudan and with whom he hoped to establish a power base in direct opposition to the Mahdi.

Zubair Pasha hated Gordon for having hanged his son during his previous spell as Governor of Sudan and for destroying his lucrative trade in human lives, but he did wish to re-establish his influence in the region. Even so, he did not shy away from telling Gordon that he desired nothing more than to see his blood seep into the sand and his bones drying in the sun, but it was in the end the British Government that prevented Gordon from striking a deal with a known slave-trader - public opinion would not countenance it - Gordon’s Plan A had been shredded and he had no Plan B.

He arrived in Khartoum on 18 February 1884, to the rapturous reception usually reserved for a Messiah but any thought that his presence alone would deter or deflect the Mahdi from his chosen path were soon quashed and by 18 March he was under siege. Still, he was confident that his continued presence in Khartoum would force the British Government to intervene militarily.

In the meantime, he shored up his support in Khartoum by abolishing taxation, putting an end to arbitrary arrest, and, though it would only be a temporary measure, re-established slavery. He had already successfully evacuated 2,500 Egyptian and European citizens from the Sudan as was his remit, but the avenues of escape had long since been closed.

He now proceeded to bombard the British Government with requests for reinforcements British troops, Indian troops, Turkish troops, it didn’t matter. Give me the resources and I will defeat the Mahdi, he told them. But Gladstone in London refused to be bullied by Gordon despite the fact the press was demanding a Relief Column be sent and the Conservative Opposition in Parliament introducing a motion of censure that Gladstone only narrowly defeated. Still, he refused and instead demanded to know why Gordon wasn't evacuating the Sudan, including himself, as he had been instructed to do?

In Khartoum, Gordon who was busy fortifying the city remained just as unyielding - he would either defeat the Mahdi or die a Christian Martyr.

He was fortunate in that the North and West of the city were protected by the River Nile but the rest was open to the desert and here he dug trenches and planted mines. He also continued to pressure the British Government. On 8 April, he wrote: "I leave you with the indelible disgrace of abandoning the garrisons."

Later that month the Northern Tribes rose in support of the Mahdi cutting off all communication with Cairo.

Gordon, now totally isolated in Khartoum could no longer be re-supplied and was aware that with more than 30,000 civilian mouths to feed he had food enough for only 5 months; a series of largely abortive attempts to replenish his stocks by raiding the surrounding area were to cost him over 1,000 soldiers killed, men he could not spare. By contrast the Mahdi's army surrounding Khartoum now stood at over 30,000 and was growing all the time. But despite his numerical advantage he resolved not to attack the city as long as the waters of the Nile remained high. Instead, he contented himself with bombarding the city and terrorising its citizens.

In Britain the cries of "Save Gordon" were becoming deafening and Gladstone ordered him to abandon Khartoum and save himself regardless of any previous instructions he may have had. He continued to refuse saying his honour would not permit it.

It was only after Queen Victoria personally intervened that Gladstone relented and agreed to send a Relief Column to the Sudan under the command of Sir Garnet Wolsey. This was in July 1884 but because of delays it did not arrive in the Sudan until January of the following year.

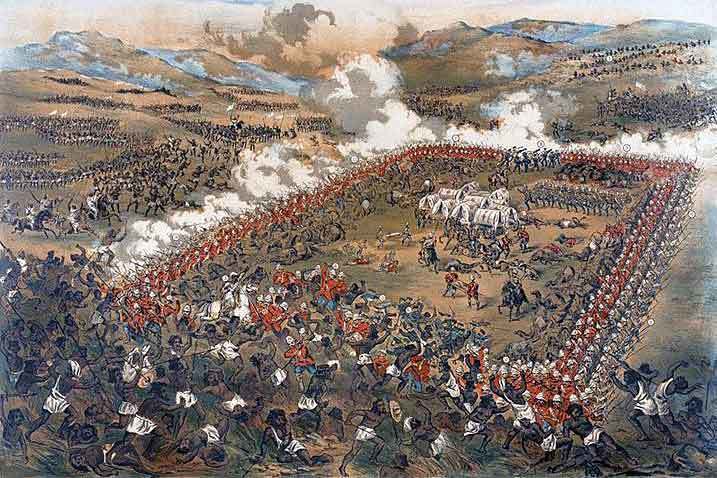

On 17 January, the Relief Column was ambushed by the Mahdi's forces at Abu Klea. It was a fierce and brutal fight and at one point the British Square was broken, an almost unknown occurrence.

The battle failed to stop the British advance, but it did delay it, a delay that was to prove critical. Aware that time was running out, Wolsey organised a Flying Column to set off at once for Khartoum, the rest of the army would follow.

The Mahdi knew full well that the Relief Column was closing but by now the Nile's waters had receded and could be crossed on foot. On 26 January 1885 he ordered his army, now 50,000 strong, to attack.

Resistance was patchy as Gordon's troops half-starved, exhausted, and demoralised crumbled before the onslaught of the Mahdi's hordes buoyed by religious fervour and the certainty of victory. Despite all of Gordon’s engineering expertise, his elaborate trench works, minefields and gun emplacements within a few hours it was all over.

As the battle neared its conclusion Gordon appeared on the balcony of the Governor's Residence in the full regalia of his office.

His Sudanese servant who survived the onslaught described how Gordon, sword in hand, discharged his pistol into the mass of warriors thronging below him before being speared in the chest.

The Mahdi had ordered that Gordon be spared and taken alive but instead, his head was hacked off and taken to his camp on a spear. Angered that his express wishes had been disobeyed he refused to look upon it but nevertheless ordered that the head be:

"Transfixed between the branches of a tree, where all who passed it could look in disdain, children could throw stones at it, and the hawks of the desert could swoop and circle above."

The Mahdi had achieved his great victory over the mighty Christian warrior but only just for Wolsey’s Flying Column arrived in Khartoum just two days later only to find the defenders dead and the city abandoned.

In Britain the blame for Gordon's death was placed firmly at the door of Prime Minister Gladstone. He had long been referred to as the G.O.M the Grand Old Man of British politics, now he was referred to in the press and ridiculed in Music Hall as the M.O.G the Murderer of Gordon.

Muhammad Ahmed, the Mahdi, the Chosen One, was now the sole ruler of a Sudan which had gained its independence through force of arms and had rid itself of the hated Infidel. He now instituted strict Sharia Law and sought to spread his revolution throughout the whole of the Islamic World. But it was not to be, just five months after his great victory at Khartoum, he too was dead.

In death Chinese Gordon became Gordon of Khartoum, the archetypal Victorian hero devout, brave, honourable - a Christian Martyr.

In 1898, another Victorian British hero, Herbert Horatio Kitchener would avenge Gordon and re-conquer the Sudan by defeating a new Mahdi at the Battle of Omdurman.

Share this post: